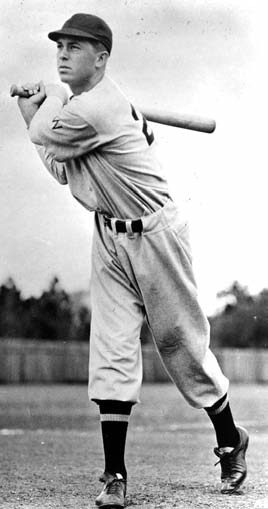

Cecil Travis

Cecil Howell Travis was a three-time All-Star who played in twelve Major League seasons between 1933 and 1947, all of them with the Washington Senators. Playing primarily as a shortstop, Travis hit .300 in eight of his first nine Major League seasons. A three-time All-Star, he had his best year in 1941, when he hit .359 (second in the American League), led both leagues in hits (218), and was named by The Sporting News as the best shortstop in baseball. After missing nearly four seasons serving in the Army during World War II, earning the Bronze Star, Travis returned to the Senators at the end of the 1945 season, but he was never able to regain his prewar all-star form.

Cecil Howell Travis was a three-time All-Star who played in twelve Major League seasons between 1933 and 1947, all of them with the Washington Senators. Playing primarily as a shortstop, Travis hit .300 in eight of his first nine Major League seasons. A three-time All-Star, he had his best year in 1941, when he hit .359 (second in the American League), led both leagues in hits (218), and was named by The Sporting News as the best shortstop in baseball. After missing nearly four seasons serving in the Army during World War II, earning the Bronze Star, Travis returned to the Senators at the end of the 1945 season, but he was never able to regain his prewar all-star form.

Travis was born on August 8, 1913, on his parents’ 200-acre farm in Riverdale, Georgia, a small town near Atlanta. He was the youngest of ten children raised by James and Ada Travis. Cecil and his five brothers worked on the family farm. “I naturally had my share of farm work to do…but being the youngest of the children, escaped much of the hard work,” Travis would remember later (The Washington Post, February 14, 1935). Baseball offered one of the few means of escape: “Didn’t matter if we use rocks or sticks just as long as we were playing” (Jack DeVries). “Instead of chopping cotton, I’d pick up rocks and whack ’em with my hoe” (Dave Kindred).

Travis entered Fayetteville High School in 1927. One of his teachers was Roy Hodgson, a former athlete at the University of Georgia. Hodgson formed a baseball team and installed Travis as the team’s shortstop. During summers, Travis played amateur baseball for the Fayetteville team in the Flint River League. The left-handed swinging Travis (who threw right-handed) developed the reputation of a natural line-drive hitter who could hit anybody. Ex-major leaguer Kid Elberfeld arranged for Travis to be given a tryout at Tubby Walton’s Baseball University, a baseball training school in Atlanta. Travis was awarded a scholarship to attend the school, and to his family’s alarm, he turned down a scholarship from Georgia Tech in order to pursue baseball as a career.

Elberfeld next took Travis to try out for the Chattanooga Lookouts, who paid Elberfeld a finder’s fee and signed Travis. He was first sent to play semi-pro ball in Newport, Tennessee, before his call-up to Chattanooga, for whom he hit .429 in limited play in the second half of the 1931 season. In 1932, he was named Chattanooga’s starting third baseman and led the team in batting average and triples, as the Lookouts won the Southern Association title and Dixie Series championship.

In 1933, Travis was invited to spring training by the Washington Senators, Chattanooga’s parent club. After nearly making the team that spring, Travis was called up from Chattanooga to fill in for injured third baseman Ossie Bluege on May 16. Arriving at Griffith Stadium just one-half hour before game time, Travis had one of the most remarkable Major League debuts in baseball history, collecting hits in his first fout at-bats and finishing the day with five hits. It was the first time since Fred Clarke’s debut in 1894 that anyone had collected five hits in his first game; no other player has since managed this feat. Travis hit .302 in limited duty for the Senators that season, and even though he was on Washington’s World Series roster, his teammates voted him a share of the team’s bonus for winning the American League pennant.

Travis won the starting third base job over Bluege in 1934. He hit his first major league home run on June 23 off the Detroit Tigers’ Vic Sorrell. Travis batted .319 in this first full season in Washington, overcoming a terrifying early season beaning by Chicago’s Thornton Lee that sidelined him for several games. (In his first game back, Travis faced Lee again and tripled on the southpaw’s first offering.)

Travis battled injuries throughout the early stages of his career, and he was dogged by criticisms that he was not the defensive player that Bluege was. The team shuffled Travis from position to position in both the infield and outfield over the next two seasons as it sought to keep his bat in the lineup. He was named the team’s full-time shortstop in 1937 and responded by playing solid defense. In 1938, he earned his first All-Star selection but did not play in the game.

In 1939, Travis-naturally thin at 6’1″ and 185 pounds-suffered two bouts with the flu and lost considerable weight from his already lanky frame. He rebounded to hit .292, the first time in his professional career that he failed to break the .300 mark. That year, he participated in an all-star exhibition game in Cooperstown, New York, to celebrate the dedication of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. In 1940, playing mostly at third base, a healthy Travis rebounded to hit .322 and earn his second All-Star selection. This time, he not only played in the game but also was in the starting lineup and led off for the American League.

As Travis emerged as a star in the league, he drew interest from other teams, especially the perennially contending Detroit Tigers. One persistent rumor had Travis going to the Tigers in exchange for either all-star Rudy York or future Hall of Famer Hank Greenberg. But Washington never traded Travis, and he remained with the Senators his entire career, never playing in the postseason.

The historic 1941 baseball season set the stage for Travis’ most remarkable season in the majors. After experimenting that spring with a heavier bat, different grip, and a stance farther back in the batter’s box, the former opposite-field hitter emerged as a pull hitter with some pop. He went on to set career highs in batting average (.359), doubles (39), triples (19), home runs (7), RBIs (101), and runs scored (106). He also collected a career-best 218 hits, which led all of baseball that season-a surprising fact when considering that Joe DiMaggio staged a record 56-game hitting streak and Ted Williams hit .406 that same year. In the classic 1941 All-Star game in Detroit, Travis’ take-out slide at second base in the ninth inning prevented a double play and kept the game alive, allowing Ted Williams to follow with his memorable game-winning home run.

Soon after Pearl Harbor, Travis was inducted into the United States Army. He was stationed at Camp Wheeler in Georgia, where he played on the camp’s baseball team. In May 1942, he was granted leave to play in a benefit game at Griffith Stadium for Dean’s All-Stars, organized by Dizzy Dean, who were pitted against the Homestead Grays of the Negro Leagues. The highlight of the game was when Travis faced off against the great Satchel Paige, whom the Grays had borrowed for the exhibition; Travis singled in the first at-bat but Paige struck him out in the second at-bat. The Paige-Travis confrontations have been cited as an important moment in the early stages of integrating the sport. Travis and the Camp Wheeler club played in the national semipro tournament in August and won the championship. On September 12, 1942, Travis married Helen Hubbard of Atlanta, Georgia. The couple would raise three sons: Cecil Anthony, Michael and Ricky.

In 1944, Travis was transferred to Camp McCoy in Wisconsin. He was a star on the McCoy baseball team, which played against semipro and military teams throughout the region and won the Wisconsin state championship. That autumn, as a member of the Special Forces in the 76th Infantry Division (nicknamed “Onaway” Division), Travis was sent to Europe for active duty. The 76th was stationed briefly in England before crossing the channel and entering the European Theater in December. That winter, the 76th performed “mop-up” duty in following behind the Germans as Hitler’s forces retreated from the Battle of the Bulge. American soldiers battled the elements during that cold winter; Travis developed frostbite to two toes of his left foot and spent time in a hospital in Metz, France, before rejoining his unit. Onaway Division pursued Hitler’s army on into Germany and, following the surrender of Germany in May 1945, remained as part of the occupying forces. Travis managed a baseball team for the 76th that participated in a European Theater tournament.

After the 76th was deactivated in June, Travis returned to the States. He was training for reassignment to the Pacific Theater when the Japanese surrendered, ending the war. A civilian once again, he rejoined the Senators lineup in September, but it was clear that he was not the same player who had compiled a .327 career batting average before the war. He hit .241 that September, and despite some brief moments of brilliance at the plate (including six straight hits over two games in May) hit only .252 in 1946, his last season as a full-time player. The Senators celebrated “Cecil Travis Night” in his honor at Griffith Stadium on August 15, 1947. In the ceremony, which was attended by the former Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Travis was showered with gifts, including a De Soto automobile and a 1,500-pound Hereford bull. He officially retired after the 1947 season and worked as a scout in the organization until 1956. He settled back on his Riverdale farm with his Helen and their youngest son, Ricky.

Travis is remembered not only as a pure, line-drive hitter but also as one of the classiest players in the game. He was a quiet, unassuming star, and American League umpires once voted him their favorite player. Such names as Ted Williams, Bob Feller, and Bowie Kuhn (who served as a batboy and scoreboard operator for the Senators during Travis’ tenure) have called for Travis’ induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Travis supporters point out that the war had effectively ended his career just as he was reaching new heights, and that even with his precipitous postwar decline, his career .314 compares favorably with all but two Hall of Fame shortstops (Honus Wagner and Arky Vaughan). Characteristically, though, Travis himself refuses to campaign for himself. “I was a good player, but I wasn’t a great one,” he told Furman Bisher of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (October 3, 1999). He has never bemoaned the playing years lost to military service. “We had a job to do, an obligation, and we did it. I was hardly the only one” (Marty Appel). Travis was inducted into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame in 1975 and into RFK Stadium’s Hall of Stars in 1993.

Cecil Travis passed away on December 16, 2006, of congestive heart failure, on his farm in Riverdale, Georgia. He was 93.

Sources

Appel, Marty. Yesterday’s Heroes: Revisiting the Old-Time Baseball Stars. New York: Morrow, 1988.

Bisher, Furman. The Furman Bisher Collection. National Books Network, 1989.

Bloodgood, Clifford. “The Leading Socker of the Senators.” Baseball Magazine. Vol. 60, Issue 4, March 1938.

Bloomfield, Gary. Duty, Honor, Victory: America’s Athletes in World War II. Guilford, Conn.: The Lyons Press, 2003.

Bullock, Steven. Playing for the Nation: Baseball and the American Military during World War II. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

DeVries, Jack. “Travis Was a Silent Hit in ’41.” USA Today Baseball Weekly. Volume 1, Issue 17, July 26, 1991.

Fayette County (Georgia) Historical Society. Carolyn Cary, Official County Historian.

Finoli, David. For the Good of the Country: World War II in the Major and Minor Leagues. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2002.

Gammon, Wirt. Your Lookouts from 1885. Chattanooga: Chattanooga Publishing, 1955.

Kindred, Dave. “Memories Frozen in Time,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1995.

Lavin, Thomas. “Cecil Travis: Forgotten Star of Another Era.” Baseball Digest. Volume 43, Issue 11, November 1983.

Holway, John B. “Does Cecil Travis Belong in the Hall of Fame?” Baseball Digest. Volume 52, Issue 5, May 1993.

Kirkpatrick, Rob. Cecil Travis of the Washington Senators: The War-Torn Career of an All-Star Shortstop. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2005.

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. “Cecil Travis” file.

Newville, Todd. “Remembering…Cecil Travis.” Baseball Digest. Volume 62, Issue 5, May 2003.

Povich, Shirley. The Washington Senators. New York: G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1954.

Southern Association. Joey Elger, Media Coordinator.

Snyder, Brad. Beyond the Shadow of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

Walton, Tubby, as told to James Quillian Maxwell. The Life Story of Tubby Walton. 1968: self-published.

Joseph J. Hutnik and Leonard Kobrick, eds. We Ripened Fast: The Unofficial History of the Seventy-Sixth Infantry Division. Frankfurt: Verlag Otto Lembeck, 1944.

Full Name

Cecil Howell Travis

Born

August 8, 1913 at Riverdale, GA (USA)

Died

December 16, 2006 at Riverdale, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.