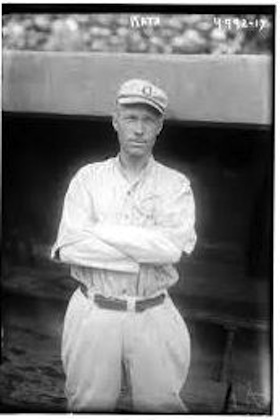

Morrie Rath

Morrie Rath’s life could have been a Hollywood movie – the type of movie where the lead character keeps getting back up after getting knocked down. And for Rath’s movie, the final scene would have played out on October 1, 1919, during the first game of the infamous 1919 World Series. On the biggest stage in all of sports at the time, Rath, twice kicked to the curb by major-league teams, given up by many teams as a career minor leaguer, was leading off the game for the Cincinnati Reds.

Morrie Rath’s life could have been a Hollywood movie – the type of movie where the lead character keeps getting back up after getting knocked down. And for Rath’s movie, the final scene would have played out on October 1, 1919, during the first game of the infamous 1919 World Series. On the biggest stage in all of sports at the time, Rath, twice kicked to the curb by major-league teams, given up by many teams as a career minor leaguer, was leading off the game for the Cincinnati Reds.

His was a remarkable story. Serving in the Navy during World War I, he hadn’t even played in Organized Ball in 1918 but had made the Cincinnati Reds on the strength of his 1917 season with Salt Lake City of the Pacific Coast League. Not only had he become the Reds’ everyday second baseman but he had helped lead the team to the National League pennant. His season was a big reason the Reds faced the powerful Chicago White Sox in the fall classic.

So as Rath dug in against 29-game-winner Eddie Cicotte, he was determined to make good. Little did he know that he would become part of a bigger story, for Cicotte, who was possessed of pinpoint control throughout his wonderful season, plunked Rath with the second pitch of the game. Only a select few knew it was the first sign that Cicotte was involved in a scheme to throw the World Series. With the pitch, Rath’s place in a Hollywood movie was cemented but instead of starring, he’d have a bit role.

Rath’s story was so much more than one at-bat. The son of a Wild West legend and a woman less than half his father’s age, Rath moved quickly from high-school ball to the major leagues. But he never stuck for very long in the big leagues. In his first season, with the Philadelphia Athletics, he found his path to the starting lineup blocked by Frank “Home Run” Baker, a future Hall of Famer. Connie Mack, looking for some outfield help, traded him away along with the rights to Joe Jackson. A severe head injury diving into the shallow end of a pool during spring training probably contributed to Rath’s eventual demotion another season. Incredibly, he played against his nephew in the major leagues but may have never known it. And when illness plagued him in his late 50s, he took his own life.

Rath played only six seasons in the majors, three as an everyday starter. Despite having great speed, wonderful fielding skills, and a keen batting eye, he never lasted for more than two seasons at a time in the majors. According to Bill James, in a different era he may have had a longer major-league career. “He spent almost all of his career in the minor leagues just because his skills were too subtle for the men who managed the major league teams,” James wrote.1

Even Rath’s birth was filled with intrigue. Morris Charles Rath was born on Christmas Day 1886 to Carl Gottfried “Charles” Rath and Emma Nesper in Mobeetie, Texas. Charles, who was 50 years old at the time, was 30 years older than Emma. A larger-than-life-figure, he was a German-born entrepreneur who, after his family immigrated to the United States when he was 11, ran away from home at the age of 15 to make his fortune on the Western frontier. He took a Cheyenne wife, Making Out Road, at the age of 20. Making Out Road, who was much older than Rath, had been the wife of the frontiersman Kit Carson at one time. The union with Rath produced a daughter, Cheyenne Belle Rath. Her child, Mike Balenti, went on to attend the Carlisle Indian School and play for the Cincinnati Reds and St. Louis Browns.2

When tensions became tight between the Cheyenne and white settlers, Charles Rath was forced to flee and leave his family behind. Rath moved on with his life and took a legal (at least in the eyes of the US government) wife, Caroline Markley. The marriage produced three children (two of whom lived into adulthood). During this time, Rath’s businesses prospered throughout the Southwest. He made his home in Dodge City, Kansas, but also had a base of operations in Mobeetie, Texas, and Albuquerque, New Mexico.

In July 1885, with his fortunes on the wane due to a downturn in the economy, Charles filed for divorce from Caroline and moved full-time to Mobeetie, where he owned a mercantile firm, Rath-Hamburg & Co. Later that year, Emma Nesper, a “beautiful Philadelphia belle” and the sister of one of Rath’s associates, rode into Mobeetie. According to Rath family history, Emma set her sights on Charles because she thought he was wealthy. They married on March 3, 1886, in Philadelphia. Later that year Morris was born. Eight or nine years later, Emma left Charles and took Morris back to her family in Philadelphia. It’s unclear if Morris ever saw his father again from that point. Charles died in 1902.3

In Philadelphia Rath honed his athletic skills. While attending Central Manual Training School, he played football, basketball, and baseball, excelling at all three sports. After his senior season of football, the Philadelphia Inquirer called him “the best end in interscholastic circles.” After graduating in 1907, he played baseball in the competitive Philadelphia City League.4

Rath enrolled at Swarthmore College. He played quarterback for the football team and instantly made an impression. Against George Washington University, Rath kicked two 30-yard drop kicks and ran for a 30-yard touchdown. He also played basketball for Swarthmore. But when the spring rolled around, the student body voted for a lacrosse team instead of a baseball team. Several students, including Rath, formed a renegade team. It’s not clear whether the team ever played a game.5

What is clear is that Rath withdrew from Swarthmore after his freshman year. He played baseball in the spring for the Philadelphia Professionals of the Philadelphia Baseball League. On June 13 he left to play for Wilmington of the Class D Eastern Carolina League. After Wilmington won the pennant, Rath was promoted to Lynchburg of the Class C Virginia League, where he played in 12 games.6

Two stories later emerged on how Rath was discovered. One was that he was a “protégé of Al Orth,” the former Philadelphia Phillie. “Al found him and gave him a shove to faster company,” wrote the Denver Post. It seems unlikely that Orth had actually discovered Rath in Philadelphia but rather may have taken him under his wing when Rath played in Lynchburg later in 1908. Orth made his home in Lynchburg.7

As Rath’s baseball career progressed, several stories pointed to Connie Mack. It was written that Mack had found Rath while he played for Central Manual. Mack often scouted local talent and no doubt word of Rath’s exploits found its way to him. But the answer was probably much simpler than that. Dick Smith, Wilmington’s manager, was a former star in the Philadelphia Baseball League. With Rath tearing up the semipro league, Smith brought him down to Wilmington.8

Reading, Pennsylvania, of the Class B Tri-State League claimed Rath from Lynchburg for the 1909 season. Rath, who was playing third base, had large shoes to fill at Reading. The season before, Home Run Baker had held down third base for Reading. Rath responded with a great season. He was called “one of the best third sackers ever seen” in Reading. Offensively, he was a contact hitter with tremendous speed on the basepaths. He had a very good eye at the plate.9

On August 21, 1909, Rath’s excellent season came to a head when Reading sold the third baseman to the Athletics. It was reported that Cleveland, the New York Yankees, and Washington were also after Rath. After Reading’s season ended on September 7, Rath joined the Athletics. On September 28 he played his first major-league game, leading off and playing shortstop. His first hit as a major leaguer came the next day against Ed Walsh of the Chicago White Sox. Rath saw action in seven games, six in the field. With Home Run Baker playing third, Rath played four of the six games at shortstop but struggled defensively at the position. “Rath again demonstrated that short field is not his natural position,” wrote Sporting Life after a particularly rough outing on September 29.10

Rath went to spring training in Atlanta with the Athletics the following season. He played very well in the spring and made the team as a utility infielder. “[Rath] looks like a mighty good understudy for Frank Baker,” wrote Jim Nasium of the Philadelphia Inquirer.11

Rath saw very little action during the regular season, however. Both the Washington Senators and the Cleveland Naps inquired into his availability. The Senators offered Mack $3,500 for Rath but Mack was looking for an outfielder to put his championship-caliber team over the top. The Athletics were playing well and, on July 22 were in first place by 5½ games. So Connie Mack, after watching former Athletics outfielder Bris Lord, now playing for the Naps, throw out three players at the plate in a doubleheader against the Athletics, told Cleveland’s club secretary, Ernest Barnard, “Give me Bris Lord for Morris Rath and I’ll surrender my rights to [Joe] Jackson.” The next day the deal was done.12

The Naps waived third baseman Bill Bradley to make room for Rath but quickly soured on their new acquisition as he struggled at the plate. By August 8, Cleveland asked waivers on Rath though he remained with the team. On August 15 Connie Mack defended Rath in the Cleveland Plain Dealer: “I think he will show his worth sometime before long. He’s a winning player. At Reading, where I got him, Rath is considered to this day to be a better ballplayer than Frank Baker.” But on August 24, Cleveland gave up on Rath, selling him to the Baltimore Orioles of the Class A Eastern League. Rath, in 24 games for the Naps, batted just .194. He complained years later that he wasn’t given a fair chance in Cleveland.13

Though he played only 28 games with Orioles in 1910, Rath played with a chip on his shoulder, batting .346 and establishing himself as one of the best infielders in the league. The Baltimore American was suitably impressed. “[Rath] fielded in such a brilliant manner,” it wrote after the season. “[T]here was probably never a player here who made a more favorable impression on the fans than did Rath.” The Orioles wasted no time in signing Rath for the 1911 season.14

While wintering at his mother’s home in Absecon, New Jersey, along the southern Jersey coast, Rath found out that the Athletics, who had won the World Series, had awarded him a $250 share of their World Series winnings. For Rath, who had played in only seven games for the Athletics, it was an indication of the respect he generated from his teammates.15

Rath continued where he left off in 1911, tearing up Eastern League pitching. The Cincinnati Reds were rumored to have offered the Orioles $5,000 for Rath. Instead, Rath finished out the season with Baltimore, batting .340, good for second in the league, and leading the Orioles to a second-place finish. On September 1 the Chicago White Sox drafted Rath for the following season, a move that Sporting Life praised.16

Despite having tonsillitis while at spring training in Corsicana, Texas, Rath had a great spring. The White Sox moved him from third base to second to replace Amby McConnell, who had feuded with owner Charles Comiskey throughout the 1911 season and was released at season’s end despite batting .280. “It’s Maurice [sic] Rath against the field for second baseman of the White Sox for 1912,” said Chicago manager Jimmy “Nixey” Callahan. “Rath seems the logical successor of Ambrose McConnell for the middle sack this season.”17

So on Opening Day, Rath was the White Sox starting second baseman. He rewarded Chicago with a great start to the season. He was batting over .300 into May and even hit his first major-league home run off the Washington Senators’ Bob Groom on May 10. Sporting Life said, “Rath has developed into a splendid player.”18

Rath wasn’t the only newcomer to make waves. Buck Weaver was playing in his first major-league season at shortstop for the White Sox. “The showing made by Rath at second and Weaver at shortstop has been about all that can be expected of new men breaking into the major league limelight,” wrote Sporting Life. Later in the season, the two unwittingly conspired to force 45-year-old Kid Gleason, bench coach for the White Sox, to play one last major-league game when both were thrown out of a game on August 27.19

By season’s end, Rath had put together a fine performance. He led the league in games played (157) and plate appearances (709). He was third in walks (95) and fifth in singles (148). He was tops in fielding percentage (.963) and chances per game (5.4) among American League second basemen. Rath was also seen as a cerebral player as well. “Some of the White Sox stars give Morris Rath, the second baseman of Callahan’s team, credit for being the brains of the collection,” wrote Sporting Life. He was elected a director of the Baseball Players’ Fraternity, an organization created by the major-league players in 1912 after the suspension of Ty Cobb for punching a fan.20

So Rath left for spring training in 1913 full of expectations as he traveled by train to Paso Robles, California. But an incident early in camp impacted not only his season but much of his career. After the first outdoor practice of spring training, the team went swimming. Rath dived into the shallow end of the pool and suffered a bad laceration to his head. He also complained of a severe headache all night. He missed about a week of action. Even though Rath was soon back to playing, the blow to his head may have been more severe than was diagnosed.21

Indications are that the injury affected Rath’s season offensively. He struggled at the plate. The White Sox kept him in the lineup despite the fact that he was hitting around .200. But in August he was finally benched in favor of Joe Berger. In almost 300 at-bats, he had only two extra-base hits, both doubles. The White Sox gave up on Rath entirely on August 22 when they sent him to Kansas City of the American Association. In the first couple of weeks at Kansas City, Rath continued to have trouble getting extra-base hits. “When Rath moves to the plate, the outfielders move in,” wrote the Kansas City Star. But he recovered in September, ending his short stint in Kansas City hitting .292 with five doubles and two triples.22

Later that year Rath played with the White Sox for part of their World Tour with the New York Giants. He played on the United States portion of the tour. When the players left US soil in November, Rath went home.23

As with most major leaguers, rumors began that Rath was being pursued by the outlaw Federal League. However, he stayed with Kansas City in 1914. Clearly the effects of the pool incident had cleared. Rath batted .338, sixth in the league, and was named to the American Association all-star team after the season.24

To keep Rath in Kansas City for 1915, the Blues had signed him to a two-year contract for $3,000 a season, making him one of the highest-paid players in the league. But as the season wore on, the burden of the contract caused Rath to be expendable despite his batting .296 in 39 games. In June he was first dealt to league rival Louisville, but when it was discovered that Rath was nursing a sprained ankle, he was sent back without playing in a game. He was loaned to Toronto of the International League for the rest of the season. Rath played well for the Maple Leafs, batting .332 in 97 games. At the end of the season, his rights reverted back to Kansas City.25

Kansas City was reducing its payroll so it couldn’t afford to keep Rath. In November 1915 the Blues traded him to Salt Lake City for pitcher Dutch Ruether. The trade began a months-long battle between the two teams and Rath over which team was on the hook for his salary. For the first time in his career, Rath held out of spring training while the teams battled.26

Finally, in April the National Association ruled that Kansas City was to pay $600 of Rath’s salary while Salt Lake City paid $2,400. If Kansas City wasn’t satisfied, it could have Rath back at his full salary. With the ruling, Rath reported to Salt Lake City. He began the season with a 23-game errorless streak on 123 chances in the field. In May, after Kansas City appealed the ruling, the National Association changed its ruling, deciding that Salt Lake City had to pay the entire $3,000. Rath also became the Bees’ property.27

Rath was playing so well that the Bees kept him for the rest of the season. He rewarded them with an excellent season, batting .300 in 180 games. He stayed with the Bees for 1917 and had what was arguably his best season as a professional, winning the Pacific Coast League batting crown with a .341 average in 197 games and in the process becoming the first PCL player to win a batting championship without hitting a home run. (Artie Wilson of the Oakland Oaks did it again in 1949.) Rath’s great season didn’t go unnoticed. The Cincinnati Reds drafted him in September.28

But Rath had other plans. In December 1917, with a war raging in Europe, Rath enlisted in the Naval Reserve. In February 1918 he went to the naval wireless school in Philadelphia and was placed in the 4th Naval District, which had headquarters at League Island Navy Yard in Philadelphia.29

Rath was immediately recruited for the district’s baseball team, which was loaded with many current and future major and minor leaguers. The manager was Harry Davis, who had just finished a 22-year major league career. New York Yankee Bob Shawkey and Philadelphia Athletic Jing Johnson pitched while former Athletic Harry Fritz played third base. Future Philadelphia Phillies Dick Spalding and Bert Yeabsley were mainstays on the team. Even the great Eddie Collins played one game for the team. It was the only time Rath didn’t play at second base during his run with the team.30

The team made a splash when it defeated the Athletics 5-1 before a crowd of 9,000 on May 26. By comparison, the Athletics had played before 7,000 at Opening Day in Boston. This was no preseason, get-the-kinks-out game, either. The Athletics had already played 30 regular-season games.31

The team continued to play to huge crowds on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays at the Country Club for Enlisted Men, just outside Philadelphia in Rockledge, where the Blue Laws were not vigorously enforced. The team played from May through September with the season ending prematurely when Spanish Influenza broke out in camp. By early October, the deadly strain infected almost 3,000 people with 158 deaths at the 4th Naval District alone.32

After the war ended, Rath was still technically Salt Lake City property since the Reds never fully paid for him. In March 1919 the Reds sent left-handed pitcher Bob Steele to Salt Lake City to finish the deal.33

At first the Reds wanted Rath to vie for the open shortstop position. But when second baseman Lee Magee held out during spring training, Rath was moved to second. Cincinnati liked what they saw in Rath and sold Magee to the Brooklyn Robins. Almost six years after his last major-league game, Rath was a starter again in the big leagues.34

Both Rath and the Reds had remarkable seasons. Rath was a spark at the top of the order with an on-base percentage of .343 while batting .264. The Cincinnati Post called him a “lead-off man extraordinary.” Defensively, he was, as usual, excellent. He set a major-league record with 13 assists in a 15-inning game. Reds center fielder Greasy Neale said of Rath that he “never saw a better second sacker than Rath in my life. It’s a treat to play behind him and watch him handle from six to a dozen chances every game without hardly making anything resembling an error.” And the Reds won the National League pennant, putting them into their first World Series. Their opponent was the powerful Chicago White Sox.35

Rath’s counterpart on the White Sox, Eddie Collins, was widely regarded as the greatest second baseman of the era. During the buildup to the much-anticipated Series, newspapers compared Rath unfavorably to the great Collins. One of the best known sportswriters of the time, Hugh Fullerton, while previewing the Series, wrote that the Reds “appear entirely outclassed at second base.”36

But Rath held his own with Collins. With an on-base percentage of .333, Rath helped the Reds win the tainted Series in eight games. He celebrated the win by marrying Edna Morton in Cincinnati on October 11, two days after the Series ended. He had met Edna, a piano teacher in Chicago, while playing for Kansas City. The two made their home in Philadelphia.37

Rath continued his excellent play in 1920 spring training in Miami. He put on 15 much-needed pounds going into spring training and was red-hot at bat. He continued his torrid hitting into the regular season, batting over.300 into June. But a knee injury in July slowed the 33-year-old considerably. He missed a handful of games and when he got back into the lineup, he slumped. By season’s end, Rath was batting .267.38

Despite the slump, Rath had in many ways a better season than in 1919. He led National League second basemen in fielding percentage. His batting average was higher in 1920 than in 1919. But Rath walked significantly less in 1920, and as a result his on-base percentage was lower. In December 1920 rumors started that manager Pat Moran was looking to replace Rath at second.

The rumors were true. Moran had grown tired of Rath’s lack of power. Rath believed that the Reds manager felt the team was too heavy with left-handed hitters and he was the one to go. But no major-league teams were interested. On January 4, 1921, Rath was dealt to Seattle of the Pacific Coast League to complete a deal in which pitcher Lynn Brenton and infielder Sam Bohne were sent to the Reds. Seattle immediately sent Rath to league rival San Francisco.39

Reds fans were incensed. “Cincy Fans Want to Know What’s the Matter With Morris Rath,” blared a headline in the Tampa Tribune. “The passing of Morris Rath … was much deplored by the local fans,” said the article. Rath himself wasn’t thrilled with the trade. He didn’t sign until late February and was said to be contemplating retirement. “Rath was naturally peeved.”40

Whether Rath played the season unenthusiastically or if, at 34, he was on a steep downslide of his career, either way 1921 was a terrible year for him. He always lacked pop in his bat but this season it was very evident. The outfielders played so shallow that it was “like Rath is trying to bat the ball through two infields.” By mid-August, he was benched. He finished the season batting .264. On December 14, Rath announced he was retiring from baseball.41

Many minor-league teams inquired into Rath’s availability, but he turned them all down. Instead, he went back to Philadelphia and played semipro ball for a few years with teams including the powerful Strawbridge & Clothier squad. He became an excellent golfer, representing Aronimink Country Club in many tournaments. Rath also opened a sporting-goods store in Upper Darby, in the suburbs of Philadelphia. He and his wife worked at the store for the rest of their lives.42

In 1939 Rath played in an old-timer’s game at Shibe Park in Philadelphia, but the next year he missed a reunion of the 1919 Reds in Cincinnati. It’s unclear whether his health prevented him from attending. On Sunday morning, November 18, 1945, Rath shot himself in the living room of his living quarters above the sporting-goods store. He left a note for Edna that read, “I’m taking this way out before I go crazy.” He was 58 years old. Edna told the local paper that Rath “had been ill for several years.” No indication was given whether the illness was mental or physical in nature.43

The couple had no children. Rath was buried in Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill, a section of Upper Darby.

Notes

1 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Abstract (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 534.

2 Marc Simmons, Kit Carson and His Three Wives: A Family History (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003), 45-46. Making Out Road also was known as Road Maker. It’s unclear whether Balenti and Rath, who were contemporaries, knew that they were related. Balenti, who was five months older than Rath, grew up on an Indian reservation in Oklahoma.

3 Kathy Weiser, “Old West Legends. Charles Rath, Buffalo Entrepreneur,” Legends of America, . legendsofamerica.com/we-charlesrath.html, accessed May 29, 2014; Ida Rath, “The Rath Trail,” kancoll.org/books/rath/, accessed May 29, 2014.

4 Philadelphia Inquirer, November 7 and December 15, 1906, January 20 and April 6, 1907, and February 27, 1908.

5 Philadelphia Inquirer, October 19 and 20, 1907, and February 27 and March 8, 1908.

6 Philadelphia Inquirer, May 23 and June 15, 1908; Charlotte Observer, August 20, 1908; Richmond Times-Dispatch, September 9, 1908.

7 Denver Post, November 30, 1912; Chris Hauser, “Al Orth” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org/bioproj/person/9ddb48e5, accessed May 29, 2014.

8 Trenton Times, January 28, 1912; Philadelphia Inquirer, June 15, 1908.

9 Harrisburg Patriot, December 24, 1908; Philadelphia Inquirer, March 21, 1909; Sporting Life, March 27, 1909; Lebanon (Pennsylvania) Daily News, April 29, 1909.

10 Philadelphia Inquirer, August 22, 1909; Trenton Times, September 7, 1909; Sporting Life, October 9, 1909.

11 Sporting Life, March 5, 1910; Williamsport (Pennsylvania) Sun-Gazette, March 15, 1910; Philadelphia Inquirer, March 9, 1910.

12 Sporting Life, August 6, 1910; Norman L. Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 476; Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 24, 1910.

13 Sporting Life, August 13, 1910; Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 15 and 25, 1910, April 25, 1912.

14 Baltimore American, December 25, 1910.

15 Sporting Life, November 5, 1910; Baltimore American, December 25, 1910.

16 Cincinnati Post, July 24, 1911; Williamsport (Pennsylvania) Gazette and Bulletin, August 1, 1911; Jersey Journal (Jersey City) September 2, 1911; Sporting Life, September 30, 1911.

17 Trenton Times, January 28, 1912; Harrisburg Patriot, March 9, 1912; Sporting Life, March 2 and 23, 1912.

18 Baltimore Sun, April 28, 1912; Sporting Life, May 18, 1912; Bob McConnell and David Vincent, The Home Run Encyclopedia (New York: Macmillan, 1996), 1014.

19 Sporting Life, April 20 and September 7, 1912.

20 Sporting Life, September 21 and November 16, 1912; Cleveland Leader, March 9, 1913.

21 Cleveland Leader, February 19, 1913; Grand Forks (North Dakota) Herald, February 27, 1913; Salt Lake Telegram, February 25, 1913; Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, February 26, 1913.

22 Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, August 2, 1913; Oelwein (Iowa) Daily Register, August 14, 1913; Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 23, 1913; Kansas City Star, August 30, 1913.

23 Oakland Tribune, November 12, 1913; Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, December 1, 1913; James E. Elfers, The Tour to End All Tours (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 96.

24 Sporting Life, December 13, 1912, and October 24 and December 12, 1914; Philadelphia Inquirer, December 20, 1914.

25 Kansas City Star, June 13, 1915; Sporting Life, June 19, 1915; Salt Lake Telegram, November 3, 1915.

26 Salt Lake Telegram, November 3, 1915, and January 20, 1916.

27 Sporting Life, April 1 and May 13, 1916; Salt Lake Telegram, April 15 and May 13, 1916.

28 The Oregonian (Portland), September 27, 1949; Salt Lake Telegram, September 21, 1917.

29 Cincinnati Post, December 12, 1917; Canton (Ohio) Repository, January 9, 1918; Kansas City Star, February 6, 1918.

30 Philadelphia Inquirer, May 19 and 27, 1918.

31 Philadelphia Inquirer, May 27, 1918.

32 Philadelphia Inquirer, October 6, 1918.

33 Salt Lake Tribune, December 12, 1918; Pueblo (Colorado) Chieftain, March 20, 1919.

34 Cincinnati Post, March 20, 1919; Kansas City Star, April 8, 1919.

35 Cincinnati Post, June 26 and July 17, 1919; Lima (Ohio) News, August 18, 1957.

36 New Orleans Items, September 20, 1919.

37 Cincinnati Post, September 19 and October 11, 1919.

38 Miami Herald, January 3, 1920; Cincinnati Post, March 11, March 27, April 22, and July 19, 1920; LeGrand (Iowa) Reporter, June 4, 1920; Anaconda (Montana) Standard, September 12, 1920.

39 Cincinnati Post, December 14, 1920, and January 4, 1921; New Orleans States, January 4, 1921; Seattle Times, January 7, 1921; Salt Lake Telegram, January 5, 1921; Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, January 5, 1921.

40 Tampa Tribune, January 25, 1921; The Oregonian (Portland), February 21 and 22, 1921.

41 Oakland Tribune, May 14, 1921; Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 14, 1921; Flint (Michigan) Journal, December 14, 1921.

42 Baltimore Sun, January 5, 1922; Philadelphia Inquirer, May 26, June 22, and July 23, 1922; Chester (Pennsylvania) Times, May 17, 1939, and November 19, 1945; Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times, April 27, 1923.

43 Dallas Morning News, September 11, 1939; Canton (Ohio) Repository, October 2, 1940; Chester (Pennsylvania) Times, November 19, 1945.

Full Name

Morris Charles Rath

Born

December 25, 1886 at Mobeetie, TX (USA)

Died

November 18, 1945 at Upper Darby, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.