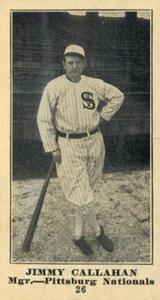

Nixey Callahan

Though known today as “Nixey” Callahan, the slim, 5-feet-10, 180-pound, right-handed jack of all trades rarely used that moniker during his big league days. Nixey was a childhood nickname that Jimmy largely left behind when his baseball skills took him from his native Fitchburg, Massachusetts to the pinnacle of the sport — although the local papers continued to use “Nixey” throughout his life. The child of Irish immigrants, born on March 18, 1874, James Joseph Callahan Jr. lost his father at age 15. A year before that, he was already helping to support his mother Margaret and his two sisters. At 14, he entered the local clothing mills. Though a certificate in his scrapbook indicates that Jimmy qualified for high school, it is unclear if he ever attended a secondary institution.1 For 75 cents a day, he toiled as a “bobbin boy.” It was dusty, dangerous work that might have ruined the lad had he not proved more valuable to his employer on the baseball diamond.

Though known today as “Nixey” Callahan, the slim, 5-feet-10, 180-pound, right-handed jack of all trades rarely used that moniker during his big league days. Nixey was a childhood nickname that Jimmy largely left behind when his baseball skills took him from his native Fitchburg, Massachusetts to the pinnacle of the sport — although the local papers continued to use “Nixey” throughout his life. The child of Irish immigrants, born on March 18, 1874, James Joseph Callahan Jr. lost his father at age 15. A year before that, he was already helping to support his mother Margaret and his two sisters. At 14, he entered the local clothing mills. Though a certificate in his scrapbook indicates that Jimmy qualified for high school, it is unclear if he ever attended a secondary institution.1 For 75 cents a day, he toiled as a “bobbin boy.” It was dusty, dangerous work that might have ruined the lad had he not proved more valuable to his employer on the baseball diamond.

Something of a prodigy on the sandlot, Jimmy began playing for his company team while in his mid-teens. Even at that age he was outclassing the locals. Over the next two years, his reputation and abilities increased. At age 16, about the same time as he had apprenticed to a local plumber, Jimmy’s professional career essentially began. He was promised a dollar if he won a game against another local team. Jimmy won the game, pocketed the dollar, and was soon hurling regularly for the semiprofessional team in Pepperell, Massachusetts. Because the plumber frowned on moonlighting, Jimmy played under the inventive alias of William Smith.

“Smith’s” chicanery went undiscovered for three years. Jimmy was found out, however, and dismissed from his apprenticeship. That really was no hardship, because by this point he was earning between $30 and $40 a game pitching for Pepperell, his high point being the recording of 22 strikeouts in a single game.

At the age of 19, he was spotted by Arthur Irwin, manager of the Philadelphia Phillies. Irwin signed Callahan and brought him south. Jumping directly to the Phillies lineup in 1894, he appeared in nine games, compiling a 1-2 record with a terrible 9.89 ERA. “They didn’t pay me enough salary to wreck them or make me,” Callahan later joked to John J. Ward of Baseball Magazine. “That way they could afford to take a chance with such a green youth as myself. I pitched a few games but I wasn’t a Walter Johnson with speed or a Christy Mathewson with skill so at the end of the season they decided that Philly would muddle along as best it could without my services. In short, they wished me well, propelled me gently through the door and carefully closed the door in my face. I was alone in the wide world.” 2

What would have been a moment of profound doubt and loss of self-esteem to most rookies became a bolt of inspiration for Jimmy Callahan. Realizing there were plenty of jobs to be had in the minor leagues, he wrote a letter to the Springfield (Massachusetts) Ponies of the Eastern League informing them that he “was a player of rare promise.”3 The ploy worked and he was given a starting position on the team.

Jimmy certainly lived up to his own billing, winning 32 out of the 41 games he started, helping Springfield to the pennant. When not pitching, Callahan played the outfield and second base. Kansas City of the Western League drafted Jimmy off of Springfield’s roster in 1896. He lasted one season with the Blues before being bought by the Chicago Colts of the National League prior to the 1897 season. Callahan impressed the Colts not only with his pitching, but also with his running ability, despite the fact that he rarely stole bases.

Perhaps the best thing for Jimmy in joining the Chicago Colts was his teammate and life-long friend Clark Griffith. Callahan adapted his pitching motion and style to resemble that of the “The Old Fox.” It was just what the young player needed. Jimmy’s confidence and abilities swelled under the instruction of the veteran. Like Griffith, he also relied heavily on his defense, never posting more than 77 strikeouts in an individual season. Callahan pitched well, but the Colts were not going anyplace in the standings.

The collapse of the American Association had created a bloated 12-team National League as the only game in town. The Colts could make little headway in such a congested league, finishing each season respectably but well out of first place. As the new century dawned, baseball was about to undergo a revolution and Jimmy determined to be a part of it. Of the nascent American League of 1900, Jimmy said, “I thought I had a special call to go to the American League. I was not under contract but, of course, I was held by the reserve rule. This rule is a good thing for baseball all right, just as the law that it’s wrong to take human life is a good and necessary thing, but in war time that very rule may be reversed, and so it is in baseball war. I figured that if anybody had been specially appointed to look after my interests his name was Callahan. I figured that if Callahan didn’t look after my interests there was something wrong with his noodle. So I told him to get busy.”

“I decided with myself that Mr. [Charles] Comiskey looked like a white man of large ambition and good prospects. I was getting X dollars with the Cubs. Comiskey offered me X plus Y dollars. I compared the two salaries and found that one would buy more collars and shirts than the other. While never noted as a mathematician in my school studies my mind was able to grasp that salient fact. So I decided to change my Sox, putting on the more or less white ones that Comiskey furnished, and was duly branded as a rebel, traitor and undesirable citizen by the National League after the accepted manner of baseball tradition.”4

Led by Griffin and Callahan, the White Sox won the first American League pennant, though in 1900, the league was still considered outlaw and minor. It was no longer minor the following year but it was still treated as an outlaw by the National League. Unfortunately for Callahan, his actual appearance in the newly organized American League in 1901 was delayed for a few weeks due to a broken bone in his forearm. Post-recovery, he compiled a sparkling 15-8 record with a 2.42 ERA. He was just as impressive at the plate, where the right-handed batter hit a career-best .331 for the season, with 11 extra-base hits in 132 plate appearances. The combination of Griffith and Callahan on the pitching mound helped Chicago win a second consecutive American League pennant, taking the flag by four games over the Boston Americans.

The following season, Callahan slumped to a 16-14 mark with a subpar 3.60 ERA. But he also pitched the best game of his career, a no-hitter against the Detroit Tigers on September 20. In what marked his final hurrah as a major-league pitcher, Callahan set down the Tigers in just one hour and 20 minutes, becoming the first American Leaguer to toss a no-hitter. Named manager of the White Sox the following season, Callahan pitched in just three games in 1903, posting a mediocre 4.50 ERA. Callahan transitioned to third base, where he registered a poor .895 fielding percentage but batted a solid .292. Under Callahan’s leadership the Sox finished a disappointing seventh.

Callahan remained Chicago’s manager for the first 42 games of the 1904 season before he was replaced by Fielder Jones. Nonetheless, he went on to play in 132 games for the White Sox that year, batting .261 and splitting his time between left field and second base. In 1905 he appeared in 96 games, mostly in left field, and finished the year with a .272 average and 26 steals

Callahan’s career path in baseball then took a very unusual trajectory, as he related in his inimitable style. “It was in 1906 I decided that Comiskey was drawing down his ten or twelve dollars every week (or it may have been fourteen) and was laying by a few shekels in the bank for a rainy day. In other words, he was getting fat around the waist line and every year brought a bulge in his bank account. I felt that I had given him five good years and that it was about time I began to work for James Callahan. Callahan might not be as good a man to work for as Comiskey but I was more interested in his welfare and the thought occurred to me that it wouldn’t be a bad plan if he had a bank account himself.”5

Thus began his career as semipro magnate, the sandlot king of Chicago He bought the Logan Squares semipro team and their stadium at the corner of Diversey and Milwaukee in the Logan Square section of Chicago. The club very quickly established itself as one of the finest if not the premier semipro baseball team in the country. Often called “Callahan’s Logan Squares,”6 Callahan’s club beat both participants in after the conclusion of the 1906 World Series, the White Sox and Cubs, although the team’s “semipro” lineup was augmented by several major leaguers, some of whom played under assumed names.

Callahan’s business venture did not endear him to organized baseball. The Logan Squares were declared “outlaws” by Ban Johnson and major-league teams faced fines or censure if they played the Logan Squares. Walter Johnson was once fined $100 for pitching in an exhibition game against them. Such machinations did little to curb the enthusiasm Chicago had for the local boys. On August 27, 1910, Callahan’s club won the first night game ever played at Comiskey Park, defeating the Rogers Park semipro club, 3-0, under portable lights, with Callahan himself driving in two of the three runs. Callahan amassed quite a nice bit of money in his role as stadium owner and team president.

After a few years, however, attendance started to lag and Callahan began looking for an opportunity to get back into organized baseball. He ran into Comiskey during the winter of 1910. “Commy” offered him the job of president of the White Sox but Callahan, then nearing 37 years of age, convinced him that he was not through as a player. To return to the majors, he had to get his name cleared from the ineligible list. This was accomplished by paying a fine of $700. His return to baseball in 1911 was one of the era’s most remarkable comeback stories. In a season Callahan considered his best in the major leagues, he played left field and hit .281 in 120 games, while also posting career highs in hits (131), home runs (3), RBIs (60), and stolen bases (45). Not bad for a man who had been out of the majors for five years.

During the offseason he added stage performer to his repertoire, taking a turn in front of the flood lights in Chicago as a monologist. His specialty was telling funny Irish stories, complete with the brogue. It wasn’t great theater, but it satisfied his audience. Ring Lardner noted, “Jimmy Callahan tells Irish stories admirably and deserves the laughs he gets.”7

So impressed was Comiskey with Callahan’s on-field performance in 1911 that he re-appointed him manager of the club in 1912. The team finished in fourth place that year with a 78-76 record, and Jimmy, in his last full season as a player, batted .272 in 111 games. The following year, manager Callahan confined himself to the bench for all but six games, and the White Sox again won 78 games, though the club dropped to fifth place.

From October 1913 to March 1914 Callahan’s White Sox and John McGraw’s New York Giants took their baseball teams on a world exhibition tour. Along with Comiskey and McGraw, Callahan was a major force behind the tour, putting up an undisclosed amount of money to help pay the teams’ traveling expenses. The teams barnstormed across the United States then set out for Japan, China, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Australia, Sri Lanka, Egypt, Italy, France, and Great Britain, with a personal side trip to Ireland. As far as Callahan was concerned the best parts of the tour were the teams’ visit with the Pope and the game in London, played before 20,000 fans, including King George V.

The tour was wearying, however, and the White Sox got off to a flat start in 1914 and finished the year a disappointing tied for sixth. Just before Christmas 1914, Callahan was bumped up to the White Sox front office to make room for Eddie Collins, whom Comiskey had just acquired, to serve as player-manager. (Collins didn’t want the job, however; it later ended up going to Pants Rowland.) The Pirates selected Callahan as manager in 1916. He led the team to a sixth-place finish. Callahan was dismissed midway through the 1917 season with the Buccos mired in last place.

Following his baseball career, Callahan became one of Chicago’s most successful contractors, building the entire waterworks for the Great Lakes Naval Station. On October 4, 1934, Callahan died of natural causes while visiting friends in Boston. Survived by his wife, the former Josephine Hardin, two sons, and a daughter, Callahan was buried in St. Bernard’s Cemetery in his hometown of Fitchburg.

An updated version of this biography appears in SABR’s No-Hitters book (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference,com, Callahan’s obituaries in the Chicago Tribune and New York Times, and the following:

“Who’s Who on the Diamond,” Baseball Magazine, May, 1909.

Lee, Bill. The Baseball Necrology (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003).

McGlynn, Frank. “Striking Scenes from the Tour Around the World,” Baseball Magazine, August 1914 to December 1915.

Assorted clippings from Callahan’s personal scrapbook provided by Don Bunce of Arlington Heights, Illinois. He is Callahan’s foster grandson and the closest thing to a living relative Jimmy Callahan has. All three of Callahan’s natural children have passed on and all were childless. Don was very giving of his time during a visit to Chicago as well.

Notes

1 Jimmy Callahan’s personal scrapbook.

2 John J. Ward, “Callahan, The Cast Off Manager,” Baseball Magazine, August 1916.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Undated clipping in Jimmy Callahan’s scrapbook. “Callahan’s Logan Squares” recounting the history of the team.

7 Ring Lardner, “The Biggest Bugs In Baseball,” Baseball Magazine, January 1912: 36.

Full Name

James Joseph Callahan

Born

March 18, 1874 at Fitchburg, MA (USA)

Died

October 4, 1934 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.