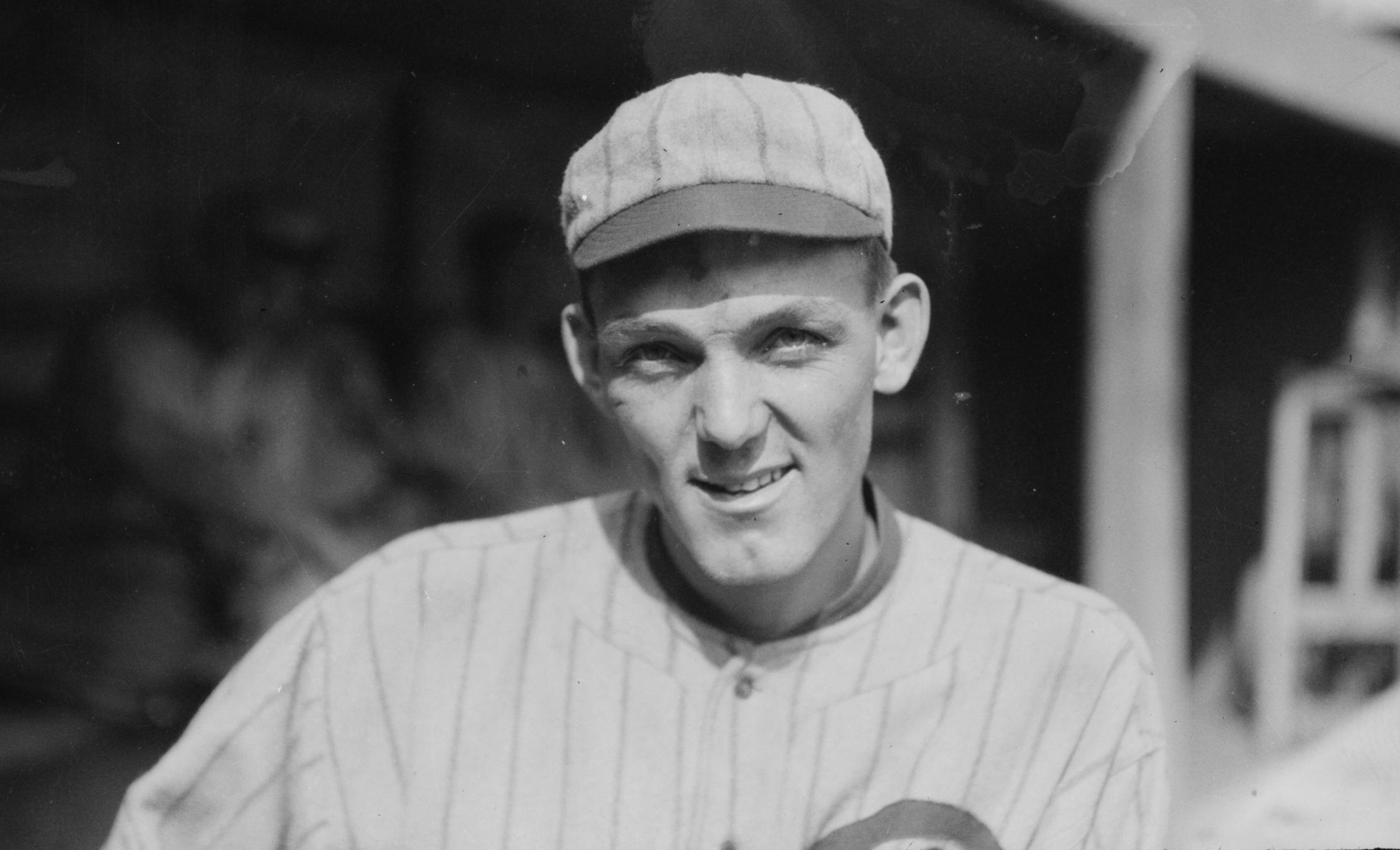

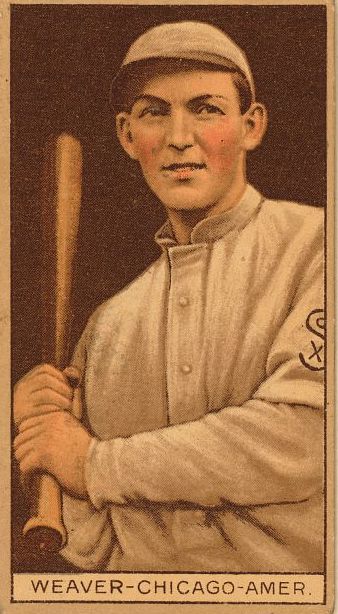

Buck Weaver

Best known as the third baseman banned from Organized Baseball for his knowledge of the 1919 World Series fix in which he did not participate, Buck Weaver spent most of his nine-year major-league career as a shortstop, only converting full time to the third sack in 1917. Initially a right-handed batter, Weaver learned to switch-hit after a poor rookie season, and from there he made his mark as one of the American League’s most resourceful players, twice leading the circuit in sacrifices, and using his excellent range to reach balls that escaped most of his peers.

Best known as the third baseman banned from Organized Baseball for his knowledge of the 1919 World Series fix in which he did not participate, Buck Weaver spent most of his nine-year major-league career as a shortstop, only converting full time to the third sack in 1917. Initially a right-handed batter, Weaver learned to switch-hit after a poor rookie season, and from there he made his mark as one of the American League’s most resourceful players, twice leading the circuit in sacrifices, and using his excellent range to reach balls that escaped most of his peers.

Nelson Algren once described Weaver as a “territorial animal … who guarded the spiked sand around third like his life.”1 Despite his competitiveness, the infectious Weaver, nicknamed the Ginger Kid,2 was also one of the most popular players of his day, known for his ever-smiling, jug-eared face that mimicked a Halloween Jack. Throughout the Deadball Era, Weaver steadily improved his game, enjoying his best season in 1920, just before he was permanently banished from the game he loved. An optimist by nature, Weaver spent the rest of his life fighting to restore his name.

George Daniel Weaver was born on August 18, 1890, in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, the fourth of five children of Daniel and Sarah Weaver. Located 41 miles northwest of Philadelphia, Pottstown had become one of the centers for the state’s emerging iron industry, and Daniel Weaver supported his family by working in one of the area’s iron furnaces.3 By late 19th century standards, the heavily unionized iron industry paid good wages, and George Weaver’s childhood was a contented one. Not very interested in school, Weaver turned his attention to baseball, where his energy and natural athletic talent were noticed at an early age by fellow players, coaches and scouts. A veteran ballplayer, Curt McGann, was so fascinated by Weaver’s passionate style of play and his upbeat, positive attitude that he nicknamed him Buck, a name in Chicago that would soon be synonymous for sympathy.4

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

Buck began his professional career in 1908 with Mount Carmel (Pennsylvania) of the outlaw Atlantic League, batting approximately .243 (the stats are incomplete) and splitting his time between shortstop and second base. After a year of semipro ball, in 1910 Weaver joined Northampton (Massachusetts) of the Connecticut State League, where he caught the eye of Philadelphia Phillies manager Red Dooin, who signed Buck to a $175-a-month contract and farmed him out to York (Pennsylvania) of the Tri-State League.5 He hit .289 in 78 games for York and in the fall of 1910, superscout Ted Sullivan of the Chicago White Sox bought Buck’s contract for $750 and assigned him to the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League.6

Separated from home for the first time, Weaver enjoyed an excellent season with the Seals in 1911, batting .282 in 182 games and drawing praise for his defensive skills. The performance was good enough to elicit an invitation to spring training with the Chicago White Sox in 1912, but just as Buck made his way to the White Sox camp in Waco, Texas, tragedy struck: His mother succumbed to illness. It was then that Buck faced a tough personal choice: Attend his mother’s funeral or attend spring training. A telegram from his father persuaded Buck to go to camp instead of returning for the funeral.7

Upon his arrival in Waco, Weaver initially told no one of his mother’s passing. When the Chicago Tribune learned what had happened, the newspaper published a feature article on the young recruit, applauding his grit. “Not a man on the squad displayed as much enthusiasm,” Tribune reporter Sam Weller observed. “He has confessed that later when he was alone in his room he couldn’t help but weep over the matter. However, he knew he could do no good by going home and he was determined to make good as a ball player and couldn’t afford to quit the training squad.”8

Despite the pain engendered by his mother’s death, Weaver impressed the White Sox with a superlative camp, winning the starting shortstop job out of spring training. Irv Sanborn dubbed Weaver the Ginger Kid after Buck gamely played with an injured left hand wrapped in bandages. “Buck hasn’t a thing against him but his age,” Weller observed. “He is only twenty years old now and lacks only in experience. In his fielding he looks every bit as fast as [Donie] Bush of Detroit.”9

In fact, as Weaver’s performance during the 1912 season demonstrated, Buck wasn’t as ready for the big leagues as the White Sox hoped or the beat writers imagined. Playing in 147 games, Weaver batted just .224 with nine walks, and led the league with 71 errors at shortstop. Knowing his position on the Chicago White Sox roster was not secure, he spent the entire offseason learning how to become a switch-hitter.10 Heading into the 1913 season with new ammunition, Buck was able to raise his batting average from .247 to .272 in the last month of the season. Despite his excellent range, Weaver’s defense remained problematic, as he again led the league with 70 errors, though he also led the circuit in putouts and double plays.

After the 1913 season Buck joined the world tour organized by Charles Comiskey and John McGraw, one of only a few White Sox players to make the trip. The touring party traveled 38,000 miles over a span of 17 weeks, not returning to Chicago until the following March. The lengthy trip may have sapped Buck’s strength for the 1914 season, as his batting average dipped to .246, with a .279 on-base percentage. Despite this poor showing, Buck had become the leader of the White Sox and was appointed team captain after Harry Lord jumped to the Federal League.11

In a 1915 poll of White Sox fans, Weaver was voted the most popular member of the team, but the next two seasons would be rough ones for him.12 After spending most of the spring of 1915 recovering from surgery to remove his adenoids and tonsils, Weaver batted .268 and scored 83 runs. The following season, however, his batting average dipped to an abysmal .227, and Weaver began splitting his time in the field between shortstop and third base. At the end of the season, Buck filed for bankruptcy when his Chicago billiard-hall operation went broke. At the time, the newspapers reported that he had no other assets.13 His salary was reportedly $6,000 a year, above average for the era.14 Weaver prided himself on being a shrewd negotiator.

Nonetheless, after the 1916 season Weaver, along with teammates Eddie Collins and Joe Jackson, publicly promised owner Charles Comiskey they would capture the 1917 American League pennant.15 This they did, thanks in large part to a superlative season from Weaver, one of the best of his career. He hit .284, the best average of his career to that point, despite missing time with a broken finger down the stretch. Switched to third base to make room for rookie shortstop Swede Risberg, Weaver proved an instant sensation at his new position, displaying excellent range, an adeptness at scooping up bunts down the third-base line, and leading the league in fielding percentage. “In stopping men coming around the bases, going after a fly ball, and digging in for hard chances Buck has few equals in the major leagues,” Baseball Magazine observed near the end of the season.16

In the 1917 World Series, Weaver batted an impressive .333, though he made four errors at shortstop after manager Pants Rowland benched Risberg for Fred McMullin and moved Weaver back to his old position. In the postgame celebration that followed Chicago’s championship-clinching victory in Game Six, Buck “danced around in a manner which indicated he had completely lost himself,” the Chicago Tribune reported. “He tossed his cap into the air and followed with his sweater and a dozen bats and three or four hats that belonged to the spectators, and if there had been anything within reach it, too, would have gone into the air.”17

The war-shortened 1918 season was a successful one for Buck, as he returned to shortstop and batted an even .300, the first time he reached that threshold in his major-league career. At season’s end Weaver went to Beloit, Wisconsin, where he worked as a mechanic in the Fairbanks-Morse manufacturing plant and played for the company’s semipro baseball team.18 As the 1919 season approached, Buck demanded a raise from Comiskey, and negotiated a rare three-year contract worth $7,250 per season – the second-highest salary on the White Sox but still less than half of what second baseman Eddie Collins was making.19

For the 1919 season, Weaver returned to third base and enjoyed another outstanding season, smashing a career-high 45 extra-base hits and batting .296. As the White Sox surged toward the pennant, some of Buck’s teammates, disgruntled over the shabby treatment they had received at the hands of Comiskey and looking for a big payday, began conspiring to throw the World Series. That September, Weaver attended two meetings regarding the proposed fix. Buck was skeptical that the scheme could work, telling his teammates and the gamblers present that throwing the World Series “couldn’t be done.”20

Weaver approached the World Series unsure of his teammates’ intentions. Rumors were rampant that the fix was on but, by all accounts, Buck wanted no part of it. Declining the advances of his crooked teammates, Weaver played his best in the Series, batting .324 with four doubles and four runs scored in Chicago’s eight-game loss to the Cincinnati Reds. In the wake of the White Sox’ stunning defeat, sportswriters suspicious of the outcome alluded to the role of the seven conspirators, but often went out of their way to praise Weaver’s efforts. “Though they are hopeless and heartless, the White Sox have a hero,” the Cincinnati Post declared.21 “He is George Weaver, who plays and fights at third base. Day after day Weaver has done his work and smiled. In spite of the certain fate that closed about the hopes of the Sox, Weaver smiled and scrapped. One by one his mates gave up. Weaver continued to grin and fight harder.”

Weaver approached the World Series unsure of his teammates’ intentions. Rumors were rampant that the fix was on but, by all accounts, Buck wanted no part of it. Declining the advances of his crooked teammates, Weaver played his best in the Series, batting .324 with four doubles and four runs scored in Chicago’s eight-game loss to the Cincinnati Reds. In the wake of the White Sox’ stunning defeat, sportswriters suspicious of the outcome alluded to the role of the seven conspirators, but often went out of their way to praise Weaver’s efforts. “Though they are hopeless and heartless, the White Sox have a hero,” the Cincinnati Post declared.21 “He is George Weaver, who plays and fights at third base. Day after day Weaver has done his work and smiled. In spite of the certain fate that closed about the hopes of the Sox, Weaver smiled and scrapped. One by one his mates gave up. Weaver continued to grin and fight harder.”

Weaver’s 1920 season, which would prove to be his last in the major leagues, was also his finest. In 151 games, Buck posted career highs in batting average (.331), on-base percentage (.365), slugging percentage (.420), runs (102), hits (208), and doubles (34). Still only 29 years old and a nine-year veteran, Weaver was at the top of his game, leading Chicago in its fight for a second consecutive pennant. But it all came crashing down on September 28, when gambler Billy Maharg alleged in the press that eight members of the White Sox had thrown the Series.22 Immediately after Maharg’s allegations were published, Comiskey had suspension letters hand-delivered to Weaver and the other accused players.23

When Weaver was served his suspension letter by White Sox employee Norris “Tip” O’Neill, he instantly marched to Comiskey’s office and declared his innocence. He was the only player of the eight accused to do so. Collyer’s Eye, a weekly periodical focused mostly on sports and gambling, later reported that Comiskey promised Weaver – separate from the other seven players – that he would be reinstated to baseball if he was acquitted in the Cook County trial.24

Though Buck requested a separate trial from the other seven players, he was forced to sit with his Black Sox teammates during the proceedings. Judge Hugo Friend, presiding over the trial, all but declared Buck innocent by saying he wouldn’t allow a conviction to stand against him if the jury ruled that way. Three hours of deliberation on August 2, 1921, returned a verdict of not guilty for all players accused. The next day the new commissioner of baseball, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, released his famous statement banning all eight of the accused for life. One clause in the statement was specifically targeted at Weaver: “… no player who sits in conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it will ever play professional baseball.”25

Unlike the other seven Black Sox, Weaver had not accepted any money to throw the Series, and there is no doubt that he played the games to win. His “crime” was simply his silence, and in this respect there was little to distinguish Weaver’s actions from those of others who had also known about the fix and yet had done nothing to stop it.

But there was a method to Landis’s harshness. By making an example of Weaver, Landis sent a message to the rest of Organized Baseball that any player who learned of a fix was guilty in the eyes of baseball unless he immediately reported it. The effect of this policy is readily apparent: Prior to Weaver’s banishment, baseball authorities usually only discovered game-fixing schemes after they had already occurred. After Weaver’s suspension, some attempted conspiracies were brought to light before they ever unfolded on the field, thanks to the honesty of players frightened by the Weaver precedent.

For instance, in 1922 New York Giants pitcher Phil Douglas was banned for life after Cardinals outfielder Les Mann reported Douglas’s efforts to extract money from the Cardinals in exchange for Douglas abandoning the Giants. In 1924 Jimmy O’Connell and Cozy Dolan, two other members of the Giants, were banned for life after they tried to give Phillies shortstop Heinie Sand $500 to throw a game. Sand immediately reported the bribe offer. In this light, Weaver’s suspension, and the object lesson it imparted to the rest of Organized Baseball for years to come, was one of Landis’s most successful moves as commissioner.

All of this was small consolation to Weaver, his family, and the legion of Chicago fans who wanted to see him reinstated. Within one year of the 1921 verdict banning Buck from baseball for life, he submitted the first of many petitions to Commissioner Landis. Weaver was turned away every time. He collected the signatures of 14,000 fans, hired a New York City attorney, and tried to get the courts to intervene.26 It was all to no avail.

After his banishment, Buck remained in Chicago, where he lived with his wife, the former Helen Cook. Buck took a job with the city as a day painter and also tried his hand in the drugstore business. With his pharmacist brother-in-law William Scanlan, he opened six drugstores on Chicago’s South Side. Noticing Buck’s business sense, Charles Walgreen, whose drugstore empire was about to skyrocket, asked Scanlan and Weaver to join him as junior partners. They declined the invitation. Then the Great Depression hit and Scanlan and Weaver were forced to close their stores.

In the meantime, Weaver continued to play ball on the semipro and outlaw circuits, sometimes playing with his former Black Sox teammates. In 1922, he joined Swede Risberg, Happy Felsch, and Lefty Williams on a tour of northern Minnesota for a series of games with local teams. In 1925, he traveled west to Arizona to form a star infield with Chick Gandil and manager Hal Chase for the Douglas team in the Copper League, which included teams in El Paso, Texas; Santa Rita/Fort Bayard, New Mexico; and across the U.S.-Mexico border in Ciudad Juarez. They were joined the following year by Williams, who joined the Douglas team before jumping to Fort Bayard.27 Weaver played in the Copper League for two summers and was immensely popular among fans throughout the league.

He returned to Chicago in 1927 and made a personal plea to Judge Landis to clear his name, which the commissioner again denied. In March of that year, Weaver agreed to play semipro ball in Chicago and it was hailed by the press as a triumphant return for the former White Sox star.28 He was frequently honored with “Buck Weaver Days” by adoring fans, and continued to play and manage for South Side teams into the early 1930s.

Into his old age, Weaver continued to pursue every avenue to return to the good graces of Organized Baseball. His final petition came in 1953, when he again requested reinstatement from Commissioner Ford Frick. In the letter, which is held by the Baseball Hall of Fame, Buck pleaded, “You know … the only thing we have left in this world is our judge and the 12 jurors and they found me not guilty. They do some funny things in baseball.”29 Weaver received no response.

Shortly before his death, Buck was interviewed by author James T. Farrell about his banishment. The good-natured man who had once exuded joy and optimism in all he did had clearly been embittered by his ordeal. “A murderer even serves his sentence and is let out,” Buck observed. “I got life.”30 On January 31, 1956, Weaver died of a heart attack at the age of 65; his body was found on West 71st Street by a Chicago policeman. Survived by his wife, Weaver was buried in Chicago’s Mt. Hope Cemetery.

Nearly a century after he last played for the White Sox, Weaver continued to enjoy strong support in the ongoing effort to clear his name. His nieces and surrogate daughters, Patricia Anderson and Bette Scanlan31, made public appearances on behalf of their uncle, including at the 2003 All-Star Game at U.S. Cellular Field and at the Society for American Baseball Research’s 2013 national convention in Philadelphia, as part of the ClearBuck.com campaign.32 Back in 1920, The Sporting News reported on Weaver’s faithful supporters with the headline “Chicago Fans Grieve Most for Weaver and Still Hope for Him.” In some quarters, that sentiment remains strong.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2015). This biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006).

Sources

Farrell, James T., My Baseball Diary. (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1957).

Stein, Irving M., The Ginger Kid: The Buck Weaver Story. (Dubuque, Iowa: Elysian Fields Press, 1992).

Farrell, James T., “Did Buck Weaver Get a Raw Deal?” Baseball Digest, August 1957.

Klein, Frank O., “Buck Weaver Back With the White Sox?” Collyer’s Eye, December 14, 1920.

Reichow, Oscar C., “Chicago Fans Grieve Most for Weaver and Still Hope for Him.” The Sporting News, October 14, 1920.

Tenney, Ross, “Weaver Dies, As Reds Roll On,” Cincinnati Post, October 10, 1919.

Weller, Sam, “Sox Recruit of 20 Shows Real Grit, Hiding Sorrow to Fight for Berth.” Chicago Tribune, March 15, 1912.

George D. Weaver v. American League Baseball Club of Chicago in the United States District Court, Northern District of Illinois, Filed 11/26/1921. Case No. 33870.

George D. Weaver v. American League Baseball Club of Chicago in the Municipal Court of Chicago. Case No. 855871.

Notes

1 Nelson Algren, “So Long, Swede Risberg,” Chicago (Vol. 30, No. 7, July 1981).

2 Chicago Tribune, May 10, 1912.

3 1900 US Census, Ancestry.com.

4 Irving M. Stein, The Ginger Kid: The Buck Weaver Story (Dubuque, Iowa: Elysian Fields Press, 1992), 3.

5 SABR Minor League Database, Baseball-Reference.com; Stein, 5.

6 Stein, 6.

7 Chicago Tribune, March 15, 1912.

8 Ibid.

9 Chicago Tribune, May 10, 1912.

10 Chicago Tribune, February 28, 1913.

11 Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1914.

12 Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1915.

13 Chicago Tribune, September 14, 1916.

14 Baseball-Reference.com.

15 Chicago Tribune, December 27, 1916.

16 John J. Ward, “Who’s Who on the Diamond,” Baseball Magazine, September 1917.

17 Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1917.

18 Stein, 121-22.

19 Bob Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Volume 6, No. 1 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Spring 2012).

20 Stein, 155.

21 Cincinnati Post, October 10, 1919.

22 Philadelphia North American, September 28, 1920.

23 Chick Gandil was the only one of the Black Sox who did not receive a suspension letter, as he sat out the 1920 season in a contract dispute with Charles Comiskey.

24 Collyer’s Eye, December 14, 1920.

25 New York Times, August 4, 1921.

26 New York Tribune, January 14, 1922.

27 Lynn F. Bevill, “Outlaw Baseball Players in the Copper League: 1925-1927.” Master’s thesis, Western New Mexico University, 1988.

28 Chicago Tribune, March 13, 1927.

29 Kansas City Star, December 27, 1953.

30 James T. Farrell, My Baseball Diary (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1957), 179.

31 Buck and Helen Weaver raised her sister’s children for 16 years after William Scanlan’s death in 1931. Helen Weaver and Marie Scanlan were very close and were buried next to each other at Mt. Hope Cemetery in Chicago.

32 At the 2003 All-Star Game, Patricia Anderson was joined by another Weaver niece, Marjorie Follett, to help launch ClearBuck.com with this author in Chicago.

Full Name

George Daniel Weaver

Born

August 18, 1890 at Pottstown, PA (USA)

Died

January 31, 1956 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.