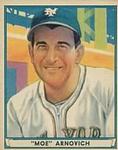

Morrie Arnovich

A glorious spring always seemed to be in store for Morrie Arnovich, as hits jumped from his bat in bunches. But base hits became scarce as July and August approached and the dog days took their toll on his batting average. The heavy woolen uniforms soaked with sweat added more misery and the once lifelike bat felt like a wagon tongue. Morrie was a small player — five foot ten and 160 pounds — with a big heart and lots of hustle. Because of his small frame, the simmering heat of summer sapped his strength. An amiable and intelligent man, Arnovich was well liked by his teammates and opposing players. Not an unusually talented ballplayer, he made up for it by hard work and a willingness to keep learning. In 1939, when Morrie was having his best year, Doc Prothro, manager of the Phils said he “would not trade Arnovich for Joe Medwick,” one of the most feared sluggers in the game (Jewish Baseball Stars, p. 79).

A glorious spring always seemed to be in store for Morrie Arnovich, as hits jumped from his bat in bunches. But base hits became scarce as July and August approached and the dog days took their toll on his batting average. The heavy woolen uniforms soaked with sweat added more misery and the once lifelike bat felt like a wagon tongue. Morrie was a small player — five foot ten and 160 pounds — with a big heart and lots of hustle. Because of his small frame, the simmering heat of summer sapped his strength. An amiable and intelligent man, Arnovich was well liked by his teammates and opposing players. Not an unusually talented ballplayer, he made up for it by hard work and a willingness to keep learning. In 1939, when Morrie was having his best year, Doc Prothro, manager of the Phils said he “would not trade Arnovich for Joe Medwick,” one of the most feared sluggers in the game (Jewish Baseball Stars, p. 79).

Morris Arnovich was born in Superior, Wisconsin, on November 16, 1910. The son of Orthodox Jewish parents Charles Arnovich and Rosy Arnovich (nee Dorf), Morrie kept Kosher all his life. He had one brother and two sisters. One of his sisters attained a master’s degree. His father owned a chain of gasoline stations. Arnovich enrolled at Superior State Teachers College but left before he graduated, to play professional baseball. He was a good athlete at Superior, starring in basketball and baseball. At the school he earned the nickname of “Snooker” due to his proficiency at the British style of pocket billiards.

Although his parents wanted him to become a rabbi, Morrie desired a professional baseball career. Charles Arnovich nevertheless took pride in his son’s baseball accomplishments. Playing in the Northern League with his hometown team of Superior in 1933 and 1934, he batted .331 and .374, slamming 20 homers in 1934. One hot day in Superior, Morrie banged out three consecutive homers. Morrie counted that thrill as his best. The Phillies beckoned in 1935 and sent him to Hazleton of the New York-Penn League, where he batted .305, and his hustling spirit attracted notice. Morrie’s last season in the minors was solid, as he led the New York-Penn League in total bases and tied for the lead with 19 home runs.

Philadelphia brought Morrie up to the parent club at the end of the 1936 season. He went to bat 48 times and batted .313. The Phillies were at that time the worst team in the National League, finishing last almost every year and barely drawing enough fans to stay ahead of the bill collectors. They were the doormats of the league. But Morrie was in the Major Leagues, and he hustled in spring training in 1937, winning a starting job in the outfield. On opening day in Boston against the Braves he hit a homer that won the game for the Phils, 2-1. At a later point in the season Morrie had seven straight hits. Arnovich hustled in the outfield and wound up the season with a .290 average. Unheralded and unknown, Arnovich was making a name for himself in baseball.

In 1938, Morrie slumped a bit but still managed 138 hits and drove in 72 runs. Then in 1939, Morrie had his best year. Through June of the 1939 season he was hitting National League pitching at a .400 clip. When asked about his rise from an average hitter to a .400 one, he gave credit to an altered stance and a special bat as well as hard work. On July 19, 1939, the Philadelphia fans honored Morrie for his good work. At one point Gerry Nugent, president of the Phils, tagged Arnovich as an untouchable should any trade talk concerning Morrie arise. The dog days of August caught up with Arnovich and he finished with a batting average of .324. He was originally left off the All-Star team that year, and fans all across the nation complained bitterly about his exclusion. He was finally put on the All-Star roster, one of three Jewish players on the rosters of that All-Star game. Hank Greenberg represented the American League and Morrie Arnovich and Harry Danning the National League. Arnovich was not used in any capacity during the game, prompting the residents of Superior, Wisconsin, to vent their spleens by demanding to know why he was not used. The excuse offered was that Morrie was a right-handed hitter and that there had not been any left-handed pitching to face.

The city of Superior took pride in their local son and the local papers followed Arnovich. A banquet was held in Morrie’s honor in 1940 and the locals packed the town’s fanciest hotel. Dave Bancroft of Phillies fame was there and many dignitaries gave long speeches in praise of Morrie. Morrie was presented the usual luggage that went along with such affairs, and the entire proceedings were broadcast live over local radio. Dave Bancroft, a star shortstop with the Phillies and Giants, had noted Arnovich’s ability while Morrie was in high school and encouraged him to keep on improving. He also urged Morrie to go to the outfield rather than play shortstop.

The 1940 season was a poor one for Arnovich. He was traded to the Cincinnati Reds early in the season. Morrie batted .250 but with his hustle helped the Reds win the National League pennant and the World Series over the Detroit Tigers. Arnovich appeared in 62 games for the champion Reds, batting .284 with 21 runs batted in and no homers. Though Arnovich was not a major player in the Reds’ World Series victory (batting just once), his hustle and presence in the clubhouse made him an asset. He was a team player and accepted his role with no reservations. At the end of the 1940 season Morrie was sold to the New York Giants for $25,000. He batted .280 in 1941. The Giants, however, were not sufficiently impressed and Morrie was sent to Indianapolis. It did not matter much, for in 1942 along with his brother Hyman, Morrie enlisted in the Army, and for the next four years he served in World War II. Morrie managed and played for a service team.

A bit of controversy had occurred in 1941 as to Morrie’s draft status. He denied that he had obtained 1B-deferred status through an appeal he had made at his local draft board. It turned out that the doctor who had examined him at the draft board had noted that Morrie was short one pair of occluding molars and should be classified as 1B. Morrie admitted to having upper and lower partial dental plates due to many of his teeth having been knocked out during basketball games. Unhappy about being considered a draft dodger, Morrie was vindicated when he produced the letter about his missing occluding molars from the doctor. It all blew over when he enlisted in 1942 and was accepted by the army. While in the army Morrie managed and played for the Fort Lewis team in Tacoma, Washington. Later in the war Morrie was an army postal clerk in New Guinea.

Arnovich returned to baseball after the war, but after playing minor league ball in 1947 and 1948 he retired from baseball as an active player. Morrie stayed in baseball as a manager in the Cubs farm system with stints in Selma, Alabama, Hutchinson, Kansas, and Decatur, Illinois. After that he returned to his hometown in Superior, Wisconsin.

Arnovich’s lifetime batting average was .287, with 577 hits and 22 homers. He had a fielding average of .981. The war undoubtedly ate into Morrie’s baseball career. Arnovich had only five full years as a major leaguer. Four years of springtime hitting he spent with the army.

Morrie married Bertha Aserson on July 10, 1956. Arnovich ran a successful sporting goods and jewelry store. He was the basketball coach at a local Catholic high school. Morris Arnovich died on July 20, 1959, at his home in Superior of a coronary occlusion. He was 49 years old. His wife Bertha survived him. There were no children. Arnovich is buried in the Hebrew Cemetery in Superior, Wisconsin.

Morris Arnovich was a small man when giants like Greenberg, DiMaggio and Williams roamed the baseball world. His intelligence, amiability and hustle, and all-round love of the game did not take second place to the greats with whom he played. No titan of baseball, Arnovich still earned respect in the game.

Sources

Horvitz, Peter S., and Joachim Horvitz. The Big Book of Jewish Baseball. New York: SPI Books, 2001.

National Baseball Hall of Fame Files. Cooperstown, New York.

New York Times, Obituary , July 21, 1959.

Ribalow, Harold U., and Meir Z. Ribalow. Jewish Baseball Stars. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1984.

Wisconsin State Board of Health Certificate of Death. Filed August 7, 1959.

Full Name

Morris Arnovich

Born

November 16, 1910 at Superior, WI (USA)

Died

July 20, 1959 at Superior, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.