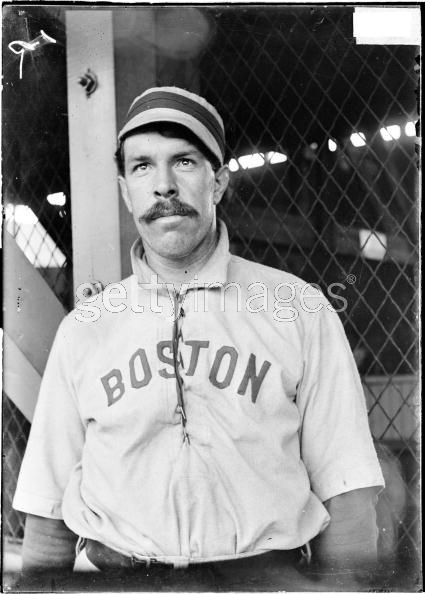

Candy LaChance

First baseman Candy LaChance was a switch-hitting 33-year-old veteran when his Boston Americans won the first World Series, in 1903. He played in every one of his team’s 141 regular-season games that year and each of the eight World Series games as well. That kind of “iron man” endurance wasn’t so uncommon at the time; teammates Hobe Ferris and Buck Freeman each matched LaChance.

First baseman Candy LaChance was a switch-hitting 33-year-old veteran when his Boston Americans won the first World Series, in 1903. He played in every one of his team’s 141 regular-season games that year and each of the eight World Series games as well. That kind of “iron man” endurance wasn’t so uncommon at the time; teammates Hobe Ferris and Buck Freeman each matched LaChance.

There was something remarkable as well about a man whose father worked as a night watchman in Connecticut and whose son (Candy) went on to do the same. In 1930, the year that Candy turned 60, he lived with family close by. His brother Edward lived at 184 Boyden Street in Waterville Village, a neighborhood in Waterbury, Connecticut, with his wife and two children. His sister Josephine lived at 192 Boyden Street with another sister and two brothers, and Candy (he was George Joseph LaChance) lived at 204 Boyden Street with his wife, Mary, and two of their grown children, George Jr. (34 years old) and Gladys (22). Candy worked as a watchman in a metalworks facility in Waterbury.

The LaChance family came from French Canadian background. George and Solomina LaChance had seven children living with them at the time of the 1910 Census in Waterbury, the eldest being 28. Candy and his family lived next door. Candy was born on Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1870, in Putnam, Connecticut.

LaChance first turns up in baseball history at the age of 20, paying semipro ball as a catcher for Fred Klobedanz, who ultimately pitched five seasons for the National League’s Boston Beaneaters. The two played in a game at Naugutuck, Connecticut, in 1890 against the visiting Boston Reds of the Players League. In 1891 LaChance played for Waterbury in the Connecticut State League. Both LaChance and Klobedanz played regularly for Portland in the New England League in 1892. LaChance signed with Wilkes-Barre (Eastern League) in 1893 and appeared in some 72 games as either a catcher or right fielder, reportedly ranking sixth in the league in batting. The Brooklyn Grooms purchased his contract, and he played in 11 late-season games, six as a catcher (committing nine errors) and five in the outfield, making one error in his six chances. He hit for a .171 average. The New York Times took note of his work after a game on August 15, writing, “LaChance’s work was favorably commented upon. He looks like big ‘Sam’ Thompson of the Philadelphias, picks out good balls to bat at, is a free hitter, a fast base runner, slides skillfully, covers plenty of ground in the outfield, and apparently is not fearful of taking chances. Judging from his game yesterday, he ought to prove a good man for Brooklyn.”

(There was a story from 1888, when LaChance was a teenager. Southington and Plainville had a fierce rivalry, and for Southington’s first game that year, Candy and his friend Red Donahue walked the nine miles from Waterbury, a route that took them over the highest peak in the area, Southington Mountain. They arrived all covered with red dust, and when asked why they hadn’t taken public transport, Candy said, “Ah, we didn’t have the price.”1)

Though he played a few games as a catcher and outfielder with the 1894 Grooms, LaChance played 56 of his 69 games as Brooklyn’s first baseman – and he certainly improved his batting. He hit .318, with five home runs and 20 stolen bases. He drove in 52 runs. LaChance played the next four seasons for Brooklyn, too, driving in 111 runs in 1895 while hitting .314.

Brooklyn was pretty much always in the middle of the pack during Candy’s tenure with the team, but the year after he left (sent to Baltimore in 1899), Brooklyn won the pennant. The Brooklyns had assigned him to the ’99 Orioles just that March, two years after the first rumors that Baltimore wanted to trade for him. It was quite a team, LaChance being teammates with John McGraw, Hughie Jennings, Wilbert Robinson, and a number of other baseball luminaries. LaChance had another solid year, hitting .307 with 75 RBIs and 31 stolen bases. It was just a one-year gig.

After the season the National League contracted from 12 clubs to eight, and Baltimore was without a team. The American League was just being launched, ranked as a Class A league, and LaChance was offered a spot on the Cleveland Lake Shores as captain of the team under manager Jimmy McAleer. He hit .302 and then, in his second year, hit .303 in 1901, the first year the AL was considered a major league. On November 14 he was traded to the Boston Americans for Ossee Schrecongost. It wasn’t the most difficult trade to arrange; Charles Somers owned parts of both teams and this was one of the rearrangements that he and league President Ban Johnson made to try to create a more competitive team in the new Boston franchise. LaChance admitted to newsmen, “I am pleased to get away from Cleveland. I couldn’t work up any enthusiasm. … I think it was a case of too many young players who went up in the air on the road. I think Boston is the finest city in the country to play ball in.” Boston Globe writer Tim Murnane said that LaChance at first base in place of Buck Freeman would improve the Boston infield 20 percent since Freeman was “weak” and “LaChance is a red ace.”2 The hard-hitting Freeman was moved to the outfield. LaChance was always ranked among the best-fielding first basemen of his time. He stood 6-feet-1 and was listed at 183 pounds.

It was in Boston that LaChance probably made the more enduring name for himself. Just before the regular season began, the Americans played an exhibition game in Waterbury. LaChance was presented a diamond ring by fans from his hometown, and then had a 4-for-6 day at the plate. That was the first baseball game his father had ever attended.3 Candy was a solid member of the 1902 club, his .279 batting average one point above the team average, and he played a steady first base while appearing in every one of the team’s 138 games. More than one sports page subhead praised his fielding.

The 1903 Americans won the pennant with ease, 14½ games ahead of the second-place Philadelphia Athletics. Again, LaChance played in every game. This was the year of the first World Series, against the Pittsburg Pirates. LaChance played in every one of those games, too, again a steady middle-of-the-pack contributor. In the first World Series game ever played, he recorded two runs batted in – without the benefit of a hit, both coming on sacrifice flies. In Game Five, drawing a bases-loaded walk gave him another RBI. On the other hand, a massive drive in Game Three over the heads of the spectators in left-center field at the Huntington Avenue Grounds would have been a home run in most games, but under the ground rules of the day (to accommodate the extra paying customers by allowing them on the field), it was ruled a double. LaChance hit .222, drove in four runs, and scored five times as Boston won the World Series in eight games.

Manager Jimmy Collins brought LaChance back for the following year, but veteran baseball scribe Tim Murnane’s appraisal saw the re-signing more a matter of sentiment than merit. LaChance, he wrote, “was the weak spot in the Boston club during the great series with Pittsburg, and I doubt if anybody but Collins would have considered LaChance for next season. Yet Collins turned down as good a man as Anderson, and held onto LaChance. Collins believes in harmony, and knows that his big first baseman does the best he knows how at all times. LaChance is kind hearted and obliging to the other members of the team, and all feel kindly toward him. The team being exceptionally strong, it can afford to keep one or two players not in the top-notch class, and in this way make the other players feel doubly secure.”4

Other than the pitchers, the team returned more or less intact, and the Americans won the pennant again in 1904, with LaChance again playing every game (recording 17 putouts without an error in a game on May 7). There were rumors in late September that Boston was willing to trade him, along with $5,000, to Washington to secure Jake Stahl, but owner John I. Taylor said that “under no circumstances do we intend to replace him at first base.”5 The 1904 pennant was no easy accomplishment, since Boston battled a strengthened New York team right to the final day of the season. LaChance had two hits in the clinching game, and was the baserunner on third base in the ninth inning who scored when 41-game winner Jack Chesbro threw a wild pitch, giving Boston a 3-2 edge – held by Boston pitcher Big Bill Dinneen. The New York Giants refused to play a postseason World Series in 1904.

Candy LaChance was enjoying life, and a feature in the Christmas Day Boston Globe declared him “King of [the] Naugatuck Valley.” He’d built a new home next door to his father’s place, and had just beheaded a couple of hens as writer Tim Murnane arrived for a visit. It was work that didn’t pay off, however, LaChance said, adding saying that he would “buy my eggs at the store hereafter.” The Globe presented a nice portrait of the LaChance family home, with baseball photographs on the walls, sledding with his eldest son (8), and the like. LaChance was treated like a king, met on arrival home after every baseball season with a brass band at the rail depot and then a banquet in the city.

LaChance was brought back for 1905, but his hitting was not what it had been. His fielding was second to none, his .992 fielding percentage leading AL first basemen in 1904, but he was proving a liability at the plate. In fact, in each of his years in Boston, his average declined (.279, .257, and .227), and he was released on May 9, 1905, batting just .146 at the time. President Taylor had found a spot for LaChance in Indianapolis but accorded him an unconditional release so he would be free to choose among several Class A minor-league clubs that inquired after his services; he preferred to stay in the East and selected Montreal of the Eastern League.

LaChance hit .272 for the Royals. At the end of the year he looked to become a magnate. He signed on to help found an intended six-team Naugatuck Valley League, with him to manage and captain the Winsted team. The league never came into being, and LaChance played instead for the 1906 Providence Grays before an August deal by Providence for Hatpin Harry O’Hagan allowed him to finish his playing career in his own home town. He played in 1907 and 1908 for Waterbury in the Connecticut State League. The end was not particularly pleasant, however. Manager W.R. Durant objected to some of LaChance’s clowning around on the field during a game on June 14 and told him to cut it out. LaChance issued a quick word, which resulted in more in the clubhouse after the game, and Durant told him to leave, working out a deal that very day to send him to New Haven.6 It was some time before LaChance truly made the transition, his first game with New Haven not coming until June 29 (when he had a 3-for-5 game).

After spending 1909 away from the game, LaChance played briefly with Fall River in 1910 and worked as an umpire in the Connecticut State League. He worked his first game on May 26, and the Hartford Courant wrote that he’d worked it like a veteran: “No player made a murmur, and Candy thought it was the easiest money he had ever earned.” This was a gig which didn’t last long. Less than three weeks later, a Courant headline read, “Candy LaChance Canned” – he’d been let go as umpire. The news story editorialized a bit, essentially saying that there was no better man than LaChance at the job.7 He was seen later in the year umpiring in some semipro games, and even playing first base for the Webster, Massachusetts, team.

In 1922 LaChance played independent ball in Waterbury, but that was the last of his ballplaying. He remained active, attending games in the Waterbury area for the rest of his life and working as a watchman, as his father had before him, at the Chase Metal Works plant in Waterville, a brass factory known as the “mile-long mill” – until he took ill. After more than a year’s illness with chronic myocarditis, LaChance, then 62 years old, died of coronary failure on August 18, 1932, in Waterville, leaving his widow, Mary, and three children.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed LaChance’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Hartford Courant, August 21, 1908

2 Boston Globe, November 15, 1901

3 Boston Globe, December 25, 1904

4 Boston Globe, December 20, 1903

5 Boston Globe, September 24, 1904

6 Hartford Courant, June 15, 1908

7 Hartford Courant, June 13, 1910

Full Name

George Joseph LaChance

Born

February 14, 1870 at Putnam, CT (USA)

Died

August 18, 1932 at Waterville, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.