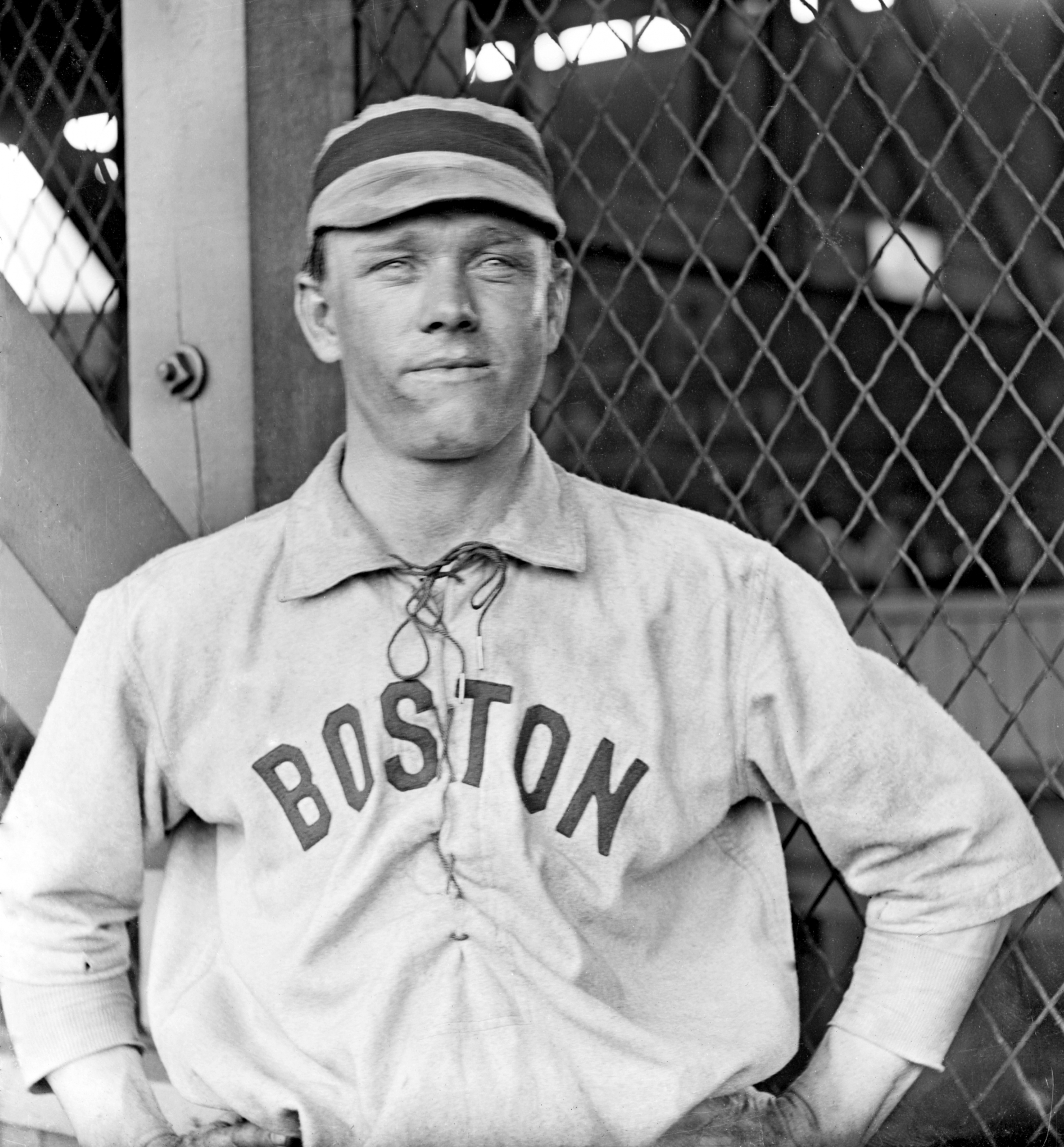

Hobe Ferris

At 5-feet-8 and 162 pounds, slick-fielding second baseman Hobe Ferris looked the part of a light-hitting middle infielder, an initial impression supported by his lifetime .239 batting average and .265 on-base percentage. But looks can be deceiving, as Ferris was one of the hardest hitters in the American League. Twenty-eight percent of the right-hander’s 1,146 career hits went for extra bases, a ratio exceeded only by 10 other American Leaguers during the Deadball Era, and higher than such renowned sluggers as Ty Cobb, Frank Baker, Elmer Flick, and Jimmy Collins. During his nine-year major-league career, Ferris ranked in the league’s top five in triples and home runs three times each. Defensively, Ferris was widely regarded as one of the best fielding second basemen of his time, and led the league in putouts twice, assists twice, and double plays once during his seven years with Boston. “At his best,” the Washington Post observed in 1908, “[his defense] made Larry Lajoie look like a second-rater.” A fierce competitor and notorious umpire baiter, the hot-tempered Ferris was later described by sportswriter Fred Lieb as a “rough and tumble old time player that could take it and dish it out.”

At 5-feet-8 and 162 pounds, slick-fielding second baseman Hobe Ferris looked the part of a light-hitting middle infielder, an initial impression supported by his lifetime .239 batting average and .265 on-base percentage. But looks can be deceiving, as Ferris was one of the hardest hitters in the American League. Twenty-eight percent of the right-hander’s 1,146 career hits went for extra bases, a ratio exceeded only by 10 other American Leaguers during the Deadball Era, and higher than such renowned sluggers as Ty Cobb, Frank Baker, Elmer Flick, and Jimmy Collins. During his nine-year major-league career, Ferris ranked in the league’s top five in triples and home runs three times each. Defensively, Ferris was widely regarded as one of the best fielding second basemen of his time, and led the league in putouts twice, assists twice, and double plays once during his seven years with Boston. “At his best,” the Washington Post observed in 1908, “[his defense] made Larry Lajoie look like a second-rater.” A fierce competitor and notorious umpire baiter, the hot-tempered Ferris was later described by sportswriter Fred Lieb as a “rough and tumble old time player that could take it and dish it out.”

Most sources record Ferris as being born on December 7, 1877, in Providence, Rhode Island. However, the Rhode Island State Archives have no record of his birth, and census records indicate that Albert Sayles Ferris was actually born in England, as were his parents, and immigrated to the United States in 1879. Having developed his baseball skills on the Providence sandlots, Ferris advanced to the next level by playing for a team in North Attleboro, Massachusetts, in 1898. One day the shortstop was missing, so Hobe, “with one side of his face swollen with a toothache,” filled in and handled 22 chances perfectly, a feat that won him a starting position. Having kept himself in fine shape by playing polo during the offseason, Ferris reported to Pawtucket of the New England League in 1899. Despite an initial batting slump, he finished with a .295 average and won accolades for his fielding. In 1900 the infielder joined Norwich in the Connecticut League, where he played shortstop and batted .292 with 31 extra-base hits.

Before the 1901 season Ferris was drafted by the Cincinnati Reds, but instead jumped to the American League to play for the Boston Americans. That same offseason, shortstop Freddy Parent signed with the club, and Ferris shifted to second base. It was initially a rough transition for Ferris, who committed 61 errors in 1901, the second highest total by a second baseman in American League history. (That same year, Detroit second baseman Kid Gleason committed 64 errors.) At the plate, the 23-year-old Ferris batted .250, drove in 63 runs, and led American League rookies with 15 triples.

The next year, 1902, Ferris again drove in 63 runs while hitting eight home runs (tied for seventh best in the league) and 14 triples. His glove work also showed signs of improvement, as he committed 22 fewer errors in the field and showed brilliant range. In one June contest, Ferris recorded 11 putouts, and on another occasion he accepted 26 chances in two consecutive games.

But it was Ferris’s numerous run-ins with umpires that garnered the most attention. In May he tangled with umpire Jack Sheridan and received a three-day suspension from American League president Ban Johnson. “Ferris deserves his suspension, and while it will hurt Collins’ club, I am glad of it,” wrote Peter Kelley of the Boston Journal. “We do not want any of the John McGraw biz in Boston, and the sooner that certain players become reconciled to that fact, the better it will be for Boston baseball lovers. I hope this will be a lesson for Hobe, for if he behaves, he will make a big name for himself.”

Ferris never reformed his ways, but he remained an integral part of the Boston club as it captured the 1903 American League pennant. In August the second baseman’s defense led to two victories in a doubleheader against St. Louis. “When the Browns broke into a rally Hobe cut them down with a triple play in one game and worked a double in the next that thrilled 19,000 fans,” one account said. “Retiring five men on two chances is quite an achievement for one day.” For the season Ferris batted an unimpressive .251, but hit a career-high nine home runs and scored a career-best 69 runs. In the Americans’ World Series triumph over Pittsburgh, Ferris recovered from a poor showing in the first game, in which he made two errors (and briefly raised suspicions that Boston had thrown the game), to make a spectacular unassisted double play on a Honus Wagner line drive in Game Two, preserving a 3-0 Boston victory. In the eighth and final game, Ferris drove in all three Boston runs off Deacon Phillippe to secure the franchise’s first world championship.

In 1904 Ferris slumped badly at the plate, as his batting average dipped to .213, but he figured prominently in Boston’s narrow victory in the American League pennant race, scoring from second base on a fly ball and error in a showdown end-of-season series with the New York Highlanders to give Boston a 1-0 victory. It was the final team triumph of Ferris’s major-league career, as the aging Boston roster unraveled from 1905 to 1907. Still in his prime, Ferris continued to post low batting averages but ranking among the league leaders in extra-base hits and providing Gold Glove-caliber defense at second base. He also continued to make headlines whenever his nasty temper flared on the ball field, as occurred on September 11, 1906.

In that afternoon’s game against the Highlanders at New York’s Hilltop Park, Boston outfielder Jack Hayden took a leisurely route on a fly ball hit to short right field, which Ferris himself failed to go after, and the result was an inside-the-park home run. Returning to the bench at the end of the inning, Ferris initiated a vile verbal attack on Hayden for what he perceived as lackadaisical play. Hayden in turn landed three stingers to Hobe’s jaw. After their teammates separated them, Ferris braced himself on a rail and thrust his foot into Hayden’s face, knocking out several teeth. The fisticuffs continued and eventually both players were arrested. Neither pressed charges, but in response to what one reporter called “the most disgraceful affair ever predicated by any ball players on the ball field,” Ban Johnson suspended Ferris for the remainder of the season. For his part, Hobe declared, “I suppose I’m a fool for being in earnest and trying to win, but that is my way. I can’t help it.” Ferris lasted one more season in Boston before owner John Taylor dealt him to the St. Louis Browns in a six-player trade. Explaining the move, Taylor suggested that Hobe had “outlived his usefulness.”

With the Browns Ferris enjoyed perhaps his best season as a professional in 1908, as he posted career highs in batting (.270), on-base percentage (.291), and RBIs (74). Because Jimmy Williams was already established at second base, Ferris shifted to third, where he combined with shortstop Bobby Wallace to form what one writer called “the stonewall defense.” Hobe adjusted very well to his new position, and led the American League’s third basemen in putouts, double plays, and fielding percentage. Browns manager Jimmy McAleer was effusive in his praise of Ferris: “I have been in the game a long while, but I have never seen a man play such remarkable ball for a team as has Ferris for us. … You never see him that he is not hustling.”

The 1909 campaign, however, was a disappointment, as Ferris’s average plummeted to .216. He claimed he had a difficult time getting in shape, and as his season deteriorated, his frustration level spiraled to the point that a sportswriter sarcastically wrote that Ferris “has a sweet disposition when he is not getting his share of base hits.” In a game against Washington he hit a fly ball to left, and as he returned to the dugout complained to Tom Hughes, the Washington pitcher, “I ought to have killed that one.” The hurler retorted, “You hit like an old woman.” Hobe applied “a few choice names to Hughes, who was willing to stop the ball game while he got at Ferris. Umpire [Jack] Egan, however, waved him back and prevented hostilities.”

After the 1909 season Ferris was released to Minneapolis of the American Association, where he produced respectable numbers for three seasons as his playing time gradually decreased. He spent the 1913 season with St. Paul in a utility role before drawing his release. Ferris played one season for Wilkes-Barre of the New York State League before that club, too, released him. Baseball Magazine clarified the reasons for Hobe’s decline: “Ferris is let out because he has slowed up both with arms and legs – finds it hard to make the throw to first, hard to stoop quickly for fast grounders.”

By 1920 Ferris, his wife, Helena, and their daughter, Natalie, had established roots in Detroit, where Hobe worked as a mechanic and occasionally played for semipro teams. As the years passed, however, Ferris became obese. On March 18, 1938, he came across a newspaper account of ex-Tiger Fatty Fothergill’s hospitalization. As he informed his wife of this story, Ferris died of a heart attack. He was 60 years old.

An updated version of this biography appeared “New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans,” edited by Bill Nowlin (SABR, 2013). The biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006), edited by David Jones.

Sources

Newspapers

Boston Globe

Chicago Tribune

Evening Times (Pawtucket)

Los Angeles Times

New York Times

Providence Journal

Washington Post

Books and articles

Anderson, David. More Than Merkle. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2000).

Browning, Reed. Cy Young: A Baseball Life. (Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 2000).

Carter, Craig, ed. The Sporting News Complete Baseball Record Book 2001.

DeValeria, Dennis, and Jeanne DeValeria. Honus Wagner. (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 1998).

James, Bill. All-Time Major League Handbook. 2nd ed. (STATS, 2002).

James, Bill. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. (STATS, 2001).

Masur, Louis. Autumn Glory. (New York: Macmillan, 2003).

Neft, David, Richard Cohen, and Michael Neft, eds. The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball 1999. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999).

Palmer, Pete, and Gary Gillette, eds. The Baseball Encyclopedia. (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2004).

Phelon, W,A., “The Month’s Parade.” Baseball Magazine, April 1915.

Reichler, Joseph. The Baseball Encyclopedia, 6th ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1985).

Reichler, Joseph. The Great All-Time Baseball Record Book. (New York: Macmillan, 1981).

Stout , Glenn, ed. Impossible Dreams. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003).

Stout, Glenn, and Richard Johnson. Red Sox Century. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000).

Thorn, John, Pete Palmer, and Michael Gershman. eds. Total Baseball, 6th ed. (New York: Total Sports, 1999).

Tourangeau., Richard. Remembering Opening Day a Century Ago.” The National Pastime, Volume 22, pp. 19-24, 2002.

Ward, John. “The Keystone Kings.” Baseball Magazine. October, 1914, pp. 43-48.

Other resources

Hobe Ferris’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Rhode Island State Archives

Heritage Quest

Full Name

Albert Samuel Ferris

Born

December 7, 1874 at Trowbridge, Wiltshire (United Kingdom)

Died

March 18, 1938 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.