José Zardón

José Antonio Zardón Sánchez played just 54 games in the majors during a single season, 1945. However, his career also took him to Venezuela and Mexico, in addition to 11 years in the US minor leagues (1944-54) and five seasons of winter ball in his homeland. The outfielder was known most for his speed and defensive ability, but he also hit for good average with mild power.

José Antonio Zardón Sánchez played just 54 games in the majors during a single season, 1945. However, his career also took him to Venezuela and Mexico, in addition to 11 years in the US minor leagues (1944-54) and five seasons of winter ball in his homeland. The outfielder was known most for his speed and defensive ability, but he also hit for good average with mild power.

Zardón was born in La Habana (Havana), the capital of Cuba, on May 20, 1922. Baseball encyclopedias cite 1923, but Zardón said, “In that era, it was common for players to trim a year or two off their ages. I guess I was no different.”1 US baseball encyclopedias also list him as “José,” and that’s how the stateside press usually referred to him – also using the Americanized nickname “Joe.” However, the press in Florida and Latin America used “Tony,” from his middle name. (Note that in Spanish culture, many first names are dual, along the lines of “Billy Bob” in the southern US.)

“I think it is a glorious thing to have been born on May 20,” Zardón said. That is Cuban Independence Day, when the island became a republic in 1902. “Of course, I was not around then,” he added humorously. After 1959, however, Cuba ceased to celebrate this holiday because Fidel Castro’s regime had come to power. “I would have been very bothered if I had been born on July 26,” Zardón said. 2 This is a reference to the 26th of July Movement, the revolutionary organization spearheaded by Castro and Ché Guevara.

Zardón’s father, Antonio, was a customs agent for most of his life. His mother was named Cecilia Sánchez Valdés. “She died on June 4, 1925, at age 34, shortly after giving birth to my younger brother, who was stillborn. They left her placenta inside of her and she became infected with bacteria. They tell me if that happened nowadays they could treat it with antibiotics.” He had one older sister, named Hilda. “She is 95 years old,” Zardón said in 2014, “and she is right in the other room.”3

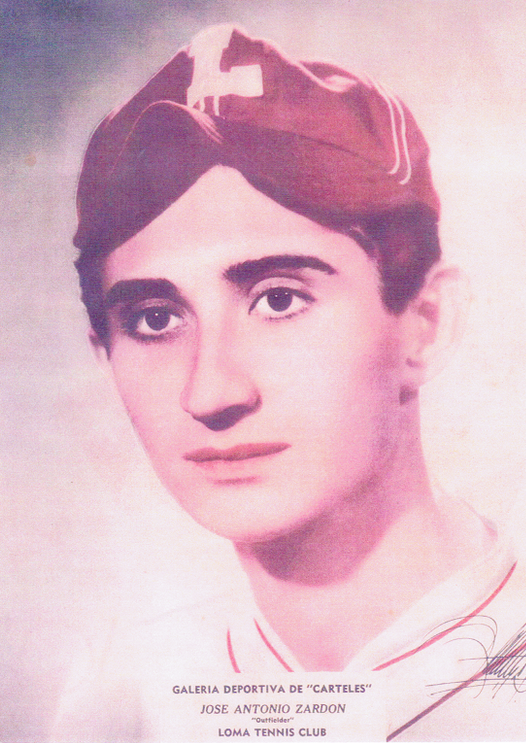

The family lived in the Jesús del Monte neighborhood of Havana. Young José Antonio played baseball on the streets. “We didn’t have any gloves. Then our neighborhood started a ball team; I was 12 or 13 and I played on the neighborhood team. We played mostly on Sundays against other teams. I continued to play in high school. My first organized team was an amateur team called the Loma Tennis Club. I was 19. After Loma, I turned pro.”4

Zardón’s first professional experience came in the summer of 1944, and it was in the United States. It’s little surprise that he became part of the Washington Senators organization. Joe Cambria, a Senators scout who was very well connected in Cuba, signed numerous players from the island for Washington. A feature that April in The Sporting News discussed Cambria’s latest haul, including Tony, billed as “Jose Zardon, a 19-year-old [sic] outfielder who covers ground.”5 “The Senators signed me for $6,000,” Zardón recalled. “I bought a model year Buick for $800. It had leather seats. It was a real head turner.”6

The new pro went to the Williamsport Grays of the Eastern League, where he batted .292 with two homers in 99 games. Zardón stole 38 bases that season and could well have led the league except that he was sidelined with an injured leg.7 (Al Gionfriddo wound up with the most steals in the EL that year, 51).

That July, with World War II still raging, three of the Cubans on the big club in Washington – Gil Torres, Roberto Ortiz, and Fermín “Mike” Guerra – decided to return home instead of registering for the US military draft. Resident aliens as well as citizens faced possible duty. Zardón and two of his compatriots on the Grays, who had obtained alien nonresident certificates in May, were able to stay without being subject to the draft. Williamsport draft board officials had referred the case to Selective Service headquarters in the Pennsylvania state capital, Harrisburg.8 As it turned out, after a short time at home Torres, Ortiz, and Guerra all decided to come back to the US and register.9

Zardón then played for the first time in Cuba’s professional winter league, signing with Marianao for the 1944-45 season. “I will never forget my first contract was for $200 for the four-month season. My first manager with Marianao was Lázaro Salazar. Tremendous player. Would have played in the majors. But Salazar left the team because, I think, he had a commitment in Mexico. Armando Marsáns then became our manager. We played at Tropical Park. Beautiful stadium. Nobody could reach those fences.”10

Zardón played little that winter, going just 4-for-22. He did receive a nickname that stuck, however – Guineo, or “Guinea Fowl” (the bird is common in Cuba). “One day during practice drills, Fermín Guerra, who later became a good friend of mine, picked me out to run the bases. The catchers would try to throw out baserunners, outfielders as well. I was a fast runner, I would commonly win the run-around-the-bases drills. There were sportswriters in attendance this day. … One of the writers [said], ‘There is a ballplayer named Tony Zardón on the field, we do not know who he is, but he runs as fast as a guinea hen.’ My father also told me that he heard it reported on the radio, ‘This player does not fly around the bases, he is like a guinea hen running them!’”11

Zardón attracted attention from Senators owner and president Clark Griffith during spring training in 1945. Griffith compared him to George Case, Washington’s swift veteran outfielder.12 Manager Ossie Bluege also liked Zardón, who got on base often during the exhibition season and opened eyes with his running catches.13

The rookie began the season with the Senators and got a seven-game trial as the starting left fielder in early May. The Sporting News wrote, “Zardon seems to have won the left field job, for the time being at least, from Jake Powell and Walt Chipple. The hungry-looking Cuban [a slender 6 feet even and 150 pounds] is fast and he has proven clever in the field ever since he reported at training camp. So far he has been beating out grounders and connecting with drives to the outfield, in between some wild swings at outside curves. However, he looks like the best bet, Bluege maintains, and will stay in left until he cracks or makes the grade.”14

It’s not entirely clear why – Zardón himself could not recall – but in May, Washington optioned him to Chattanooga in the Southern Association. Again the club was loaded with his countrymen. He hit near .300, became something of a hero in Chattanooga, and returned to Washington in mid-June because the Senators were desperate for outfield help after injuries to Case and Powell and the weak hitting of George Binks.15

Zardón got into 45 more games with the Senators over the remainder of the season. He started at all three outfield spots after his recall, but when Buddy Lewis returned from the Air Force in late July and took over the starting right-field job, Zardón went back to the bench.16 He started just four games the rest of the way but continued to shine on defense. One example came while playing center field in the nightcap of a doubleheader sweep against Boston at Griffith Stadium on August 3. “Jose Zardon … made one of the season’s most brilliant catches by spearing Bob Johnson’s 415-foot clout to the center field flagpole.”17

Griffith Stadium was a challenge for outfielders. Ballpark chronicler Andrew Clem put it this way: “If extreme variations in distances and irregular angles in the outfield fence are one of the main defining characteristics of Classic Era baseball stadiums of the early 20th century, then only two ballparks outclass Griffith Stadium: Fenway Park and the Polo Grounds.”18 “What I remember most,” Zardón recalled in 2014, “was the sign outside the front saying ‘Griffith Stadium.’ Some players complained about the lights during night games. The lamps were not very bright and the players had trouble picking up the ball, especially in the outfield. The lights did not have any adverse effect on me – I was blessed with great eyesight.”19

Overall, Zardón hit .290 for the Senators with no homers and 13 RBIs in 131 at-bats. Washington had finished last in the American League in 1944, but they came in just 1½ games behind Detroit in the race for the pennant in ’45, and Bluege got credit for the way he used his bench. “Jose Zardon, youthful Cuban, played better ball than he knew for a spell. By superb catches and a few timely hits, he kept the Nationals in the fight.”20

Yet Zardón never returned to the major leagues. In early January 1946, the Senators announced that he would go back to Chattanooga as partial payment for Gil Coan.21 Coan was a hot prospect whom The Sporting News had named Minor League Player of the Year in 1945. He was also a speedster who had beaten El Guineo in a race when both were members of the Lookouts in 1945.22

Zardón was back in the Cuban Winter League for the 1945-46 season. He remembered, “In my second year, I was traded to Cienfuegos for Alejandro Oms, a famous player in Cuba, a star. Which turns out to be a rather tragic anecdote. Because Oms, who was only 40 [actually 50], died [the following November]. The sportswriters tagged me as ‘Tony Zardón – the player who was traded for a dead man.’ It was meant to be humorous.”23 Partway through that season, Zardón was sent to the Almendares Alacranes. Again he played little, going just 3-for-18 overall.

Zardón split the summer of 1946 between Chattanooga (.277 in 34 games) and Charlotte in the Class B Tri-State League (.336 in 110 games). That was the year that Mexican magnate Jorge Pasquel sought to make his nation’s league a rival to the majors, opening his wallet. “Pasquel did some good things, offering players higher salaries,” said Zardón. “I played in Mexico after Pasquel. One season for the Mexico City Rojos [1955].”24

In the winter of 1946-47, Zardón played in La Liga de la Federación. This league sprang up after entrepreneurs Bobby Maduro and Miguelito Suárez built Havana’s new Gran Stadium. In response, Julio Blanco Herrera – the proprietor of the Cuban Winter League’s old ballpark, La Tropical – started a rival circuit. The Federation was in good standing with Organized Baseball, whereas the Cuban Winter League was using “outlaw” players who had jumped to Mexico in 1946. Attendance was poor and losses were heavy, however; the Federation folded as of year-end 1946. Zardón hit .251 in 135 at-bats for the Oriente club.

Before the 1947 summer season, The Sporting News reported that Zardón, Gil Torres, and Mike Guerra were considering Mexico because of dissatisfaction with their salaries.25 Calvin Griffith, son of Clark and then a Senators vice president, laughed at the story and said that Zardón would not be missed.26

Instead, Tony joined the Havana Cubans in the Florida International League (then Class C, later Class B). This club was controlled by Joe Cambria, Clark Griffith, and a Senators outfielder from the 1910s, Merito Acosta. The Cubans were both a showcase and proving ground for the prospects that “Papa Joe” found. The team’s pitching staff was especially notable. At various points from 1947 through 1950, it included the four prime hurlers from Cuba’s high-level amateur league: Conrado Marrero, Julio “Jiquí” Moreno, Rogelio “Limonar” Martínez, and Sandalio “Sandy” Consuegra.

Zardón stayed in Havana for five full summers as a regular, becoming the franchise’s all-time leader in at-bats and stolen bases (119), and ranking high in several other categories. Overall, he hit .274 with 20 homers and 212 RBIs in 667 games.

Zardón had yet another new team in the Cuban Winter League as the 1947-48 season came. He went to the Habana Rojos (Reds), making him one of the few players to be with all four of the teams in the league during his career. Again he found scant playing time; he went just 5-for-41.

Perhaps as a result, Zardón did not play at home for the following two winter seasons. Instead, he went to Venezuela. He recalled playing there for four seasons, but data for the early days of Venezuelan pro ball is hard to come by; the website purapelota.com shows him there for two winters, both with the club Patriotas de Venezuela. In 1948-49, he batted .367 (40-for-109) in 29 games. By his account, he beat out Alfonso “Chico” Carrasquel for the batting title by two points, but Carrasquel hit .373. With Patriotas again in the winter of 1949-50, Zardón hit .309 (54-for-175) in 43 games.

The Sporting News made no further mention of Zardón’s play in Venezuela, but Cuban sources show that he returned to Havana in the winter of 1950-51, going 6-for-25 in just nine games. The Reds won the league title that year, and then represented Cuba in the third edition of the Caribbean Series, which pitted the region’s winter-ball champions against one another in a round-robin tournament. Although Zardón went 3-for-10 in Caracas as Cuba finished second behind Puerto Rico, this is the only salient point in his career that he could not remember, although many aspects of the regular season still stood out.

“[Steve] Bilko was our first baseman. Bert Haas, third baseman. Good player. Hoyt Wilhelm was on our team. [Gilberto] Valdivia was the one who caught Wilhelm. No one envied Valdivia, having to catch that knuckleball. Chiquitín Cabrera accompanied us to the Caribbean Series. … I remember later on teasing Cabrera about how Tommy Lasorda [then with Almendares] body-slammed him when Cabrera had picked a fight during the season. Cabrera had been hit by one of Lasorda’s pitches, and he took exception to that. Lasorda could defend himself, I think he knew karate or some martial arts. … I would needle Cabrera, ask him if his back still hurt; he would tell me to go to hell. I was hit plenty of times. I took it.”27

Zardón’s career in the Cuban winter league ended in September 1951, when he was given his unconditional release by Havana manager Miguel Ángel González.28 Zardón remembered how strictly González ran his club. “One season I asked [him] for a raise to $400. He calmly pulled out a sheet of paper from his drawer and read it to me: ‘Tony Zardón. El Guineo. Games played. Times fined, times unable to play due to sickness, times late.’ Well, the games played were not that many … and the other numbers were a lot more than I remembered. Miguel Ángel told me that he would not give me a raise and to try Almendares, if I wanted. I humbly accepted the same $300 salary I had. Besides, my father was an habanista [Havana Reds fan].”29

Zardón had also played for another of Cuba’s most prominent managers, Adolfo Luque, with the Havana Cubans in 1951. He called Luque “a smart man, a tough man,” and added, “Miguel Ángel was a passive manager, compared to Luque. He and Luque were both baseball smart. But Miguel Ángel was a better-educated man than Luque, and that helped him in general with the sportswriters, more than Luque.”30

In the winter of 1952-53, Zardón got the chance to be a manager himself. It came in a newly organized, low-level Cuban circuit (for native players with brief experience in Class C and Class D ball). The idea was to provide competition for players not yet ready for the main winter league, and to develop their talent.31 Though Zardón did not offer any further detail on this experience, he said, “I managed for four seasons in Venezuela, and enjoyed it.”32

Zardón remained in the US minors from 1952 through 1954, mainly in Class B. He played with various Senators farm clubs, though he also spent a short time in the Philadelphia A’s organization in 1953. He still attracted attention for his catches; a prime example came on May 28, 1952, when he saved a no-hitter for Dean Stone (who reached the majors the next year) by pulling down a possible home run in the ninth inning.33 Zardón finished his professional career with eight games in the Mexican League in 1955. “My friend Gilberto Torres [from both the Senators and the Havana Cubans] was playing there and he got me to go.”34

“Looking back on my career, I really did not apply myself to baseball as much as I should have,” Zardón recalled. “I was engaged in la charada,” (a colloquial Spanish term for deception). “My father once told me, half the players out there wish they had your aptitude, your arm, your hands, your speed. You do not take advantage of it. You stay out too late.” He added, “There were just too many temptations for a young player. Like ‘Ladies Day’ at Gran Stadium. All women entered the park for free. Married players referred to it as ‘Divorce Day.’”35

Zardón was married twice. “My first wife was named Maria Antonia. She is deceased. We were married 28 years. We had three children, José Antonio Jr., Jacqueline, and Cecilia.” Zardón married Marlene Saumell in 1975. “We had no children. We have one dog named Sasha.” Marlene added, “I met Tony when I was working as a supervisor at Miami Jai-Alai, and he would go there. I was married before. Tony was a great stepfather to my three children.”36

After the Cuban revolution, Zardón maintained an apartment in his homeland with an old teammate from the Havana Cubans, Hiram González. Zardón was not politically inclined, and the revolution did not become personal to him until some of Castro’s agents broke into that apartment and confiscated all his trophies. He was also disturbed by the poor treatment that his father (who was anti-Castro) received.

“As a result of these affronts and still thinking myself young enough, I impulsively joined the Special Forces designated to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. I was training in Guatemala, and about ten days prior to the invasion I was injured in a parachute accident. During a practice jump, my chute did not open properly, and what saved my life was that my fall was broken by the thick branches of a ceiba tree. It took me 2½ years to fully recover. It was a covert operation, as you know, we did not use names. We were identified by numbers. But our photos were leaked and I was recognized by Castro, who decreed that there were certain ‘mercenaries’ who were not punished for their acts in the invasion and that if they ever stepped foot on Cuban soil, they would be incarcerated. I was thus branded and can never go back to Cuba.”37

Like many Cuban expatriates, Zardón settled in Florida. Around 2000, he moved to the town of Plantation, near Fort Lauderdale. “I lived in Miami before that. I worked for McArthur Dairy for many years as a driver. I also owned a taxi service, and later on, opened a restaurant in Miami. I retired a long time ago.”38

“I thank God for my long life,” said Zardón in 2011. “But I never drank a lot, nor smoked. Nor took drugs.” Even in his 90s, in early 2014, he remained physically impressive for his age, and his mental faculties had diminished little. “I live a life of leisure,” he said. “I spend most of my time at home. I walk at least a mile a day, and have a treadmill machine in my garage, which I use. On Sundays, I attend Mass, and Fridays, I attend a two-hour Bible study class. Otherwise I’m here at home.”39

In April 2014, Zardón became the oldest living major leaguer from Cuba, after the death of the legendary Conrado Marrero. He died on March 21, 2017 at the age of 94. Until the end, Zardón loved to talk baseball and share stories with friends and family.40

This biography was adapted from a March 2011 interview of Sr. Zardón, published in Lou Hernández’s book, “Memories of Winter Ball: Interviews with Players in the Latin American Winter Leagues of the 1950s” (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2013). Rory Costello conducted additional research, and Lou Hernández then re-interviewed Sr. Zardón in person at his home to gather supplementary facts on March 15, 2014. A version of this biography also appeared in “Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II” (SABR, 2015), edited by Marc Z. Aaron and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Tony and Marlene Zardón for their memories.

Sources

Internet resources

purapelota.com

Books

Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 2003).

Notes

1 In-person interview, Lou Hernández with Tony Zardón, March 15, 2014. (Hereafter cited as 2014 interview).

2 Zardón interview. In-person interview, Lou Hernández with Tony Zardón, March 2011 (Hereafter cited as 2011 interview).

3 2014 interview. Hilda predeceased Zardón at the age of 96 on April 15, 2016.

4 2014 interview.

5 Frank (Buck) O’Neill, “Nats’ Latin Quarter Spins into Register,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1944, 5.

6 In-person interview, Lou Hernández with Tony Zardón, March 2011 (Hereafter cited as 2011 interview).

7 Charles Young, “Speed Kings Fight It Out in Albany-Scranton Games,” The Knickerbocker News, (Albany, New York), September 6, 1944, 8-B.

8 “Minors’ Cubans Vary in Status,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1944, 1-2.

9 Shirley Povich, “Sinking Nats Cheer Cubans,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1944, 5.

10 2011 interview.

11 2011 interview.

12 “Label Sanchez Another Case,” The Sporting News, March 22, 1945, 12. It’s interesting to note that this snippet billed Zardón under his mother’s family name. This may have been a case of confusion with double Spanish surnames, along the lines of what happened to the Alou brothers.

13 Walter Haight, “Ferrell Bait in Senators’ Cast for Health,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1945, 16.

14 Walter Haight, “Solid Pitching Perks Up Nats; Leonard Joins,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1945, 7.

15 Shirley Povich, “Zardon Pulled Back by Nats,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1945, 8.

16 Shirley Povich, “Lewis Back in No. 2 Nat Suit; Griff Sees No. 1 Spot for Sure,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1945, 21.

17 Associated Press, August 4, 1945.

18 Andrew Clem, “Griffith Stadium,” Andrewclem.com (andrewclem.com/Baseball/GriffithStadium.html).

19 2014 interview.

20 Frank (Buck) O’Neill, “Nats Fatten on Bluege’s Hit-Run Diet,” The Sporting News, August 23, 1945, 3.

21 Shirley Povich, “Griff Scissors Nats’ Lengthy List,” The Sporting News, January 10, 1946.

22 Wirt Gammon, “Nats Get Nifty Prospect in Lookouts’ Bat Champ,” The Sporting News, November 22, 1945, 15.

23 2011 interview.

24 2014 interview.

25 “Trio Jumps to Mexico?” The Sporting News, February 12, 1947, 9.

26 Furman Bisher, “Cuban Story Funny to Nats,” The Sporting News, February 26, 1947, 18.

27 2011 interview.

28 Pedro Galiana, “Cuban Clubs Inking many O.B. Players,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1951, 37.

29 2011 interview.

30 2011 interview.

31 Pedro Galiana, “New Four-Team Loop Opens in Cuba for Class C-D Talent,” The Sporting News, November 19, 1952, 23.

32 2014 interview.

33 Bob Quincy, “Stone of Charlotte Hurls No-Hitter Over Gastonia,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1952, 11.

34 2014 interview.

35 2011 interview.

36 2014 interview.

37 2011 interview.

38 2014 interview.

39 2014 interview.

40 Rebeca Piccardo, “Tony Zardon, last surviving Washington Senator, dies in Tamarac at age 94,” The Sun-Sentinel (Palm Beach, Florida), March 23, 2017. This headline should have been phrased “oldest surviving Washington Senator.”

Full Name

José Antonio Zardón Sánchez

Born

May 20, 1922 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

Died

March 21, 2017 at Tamarac, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.