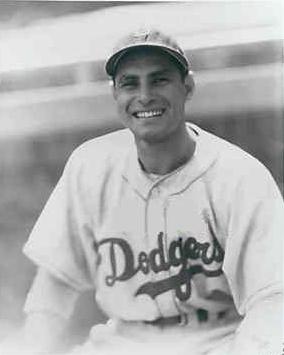

Al Gionfriddo

“Running! turning! leaping! like little Al Gionfriddo — a baseball player, Doctor, who once did a very great thing.”

“Running! turning! leaping! like little Al Gionfriddo — a baseball player, Doctor, who once did a very great thing.”

The great thing novelist Philip Roth described took place on October 5, 1947. It was Game Six of the World Series. Outfielder Al Gionfriddo, a little-used reserve, made a racing, twisting catch in deep left-center at Yankee Stadium. He robbed Joe DiMaggio of extra bases or a three-run homer and saved the game for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Alas, that would be the last time the 25-year-old ever played in the majors. Yet more than 70 years later, his spectacular grab remains a potent memory.

The drama was tense as fierce rivals dueled on the game’s center stage. Television, a World Series first that year, caught the iconic Yankee Clipper’s rare flicker of emotion as he kicked the dirt near second base. Red Barber’s exciting radio call, a classic action photo, dozens of writers and thousands of fans all helped the play live on. At root, though, is the appeal of a hard-working little guy’s moment in the sun.

Albert Francis Gionfriddo (pronounced Gee-on-FREE-doe) was born March 8, 1922, in Dysart, Pennsylvania. Dysart is northwest of Altoona, in Cambria County, about 90 miles east of Pittsburgh. This is coal country; Al’s father, Paul Gionfriddo, was a coal miner. The family’s roots are Sicilian — to be precise, Siracusa province, where the surname is common. Paul (originally Paolo) was born in the town of Solarino and learned the trade of stone mason. He emigrated to the U.S. in the early 1900s.

About 20 years previously, a man from Calabria (the “toe” of Italy’s “boot”) named Giuseppe Rametto had come to America. “Joe” settled in Dysart and was a coal miner too, as well as a barber. He gave Paul his daughter Rose’s hand in marriage. As of 1910, the young couple lived with the Ramettos — but over time they would fill their own house.

Paul and Rosie had 13 children, of whom Al was the seventh. Sad to relate, only 10 attained their majority: an older brother died in infancy; the oldest sibling, daughter Carmela, perished in an accidental fire at age 19 in 1933; and younger brother John passed away from pneumonia at about age 6. Brothers Joseph, Paul Jr. (Paulino), and Carmen and sister Mary also preceded Al. He was then followed by James, Josephine (Dolly), John, Elizabeth, Joan, and Leo.

For a time Al’s Uncle Michael, who had followed his older brother Paul to Dysart, lived in the same household. It’s also worth noting that Paul’s namesake cousin came to America and settled in Dysart too.

The Gionfriddo parents conversed in Italian, but they wanted their children to speak English. “Al could speak some broken Italian,” recalls his second wife, Susan Jacobsen Gionfriddo. “He could understand it better.” The youngsters also grew up American thanks to sports. Sue notes that the local Dysart baseball team “was half Gionfriddos, between his brothers and cousins.” Al and his younger brother Jim played for the nearby American Legion team, the Cresson Juniors. According to Jim, Al played center field and Jim played left field.

Al also attended high school in Cresson, a township roughly 12 miles south of Dysart. There, despite his small stature, he played football in addition to baseball. As a running back, he was good enough to win a scholarship to St. Francis University in nearby Loretto, Pennsylvania. However, his calling was on the diamond. At age 19 in 1941, before graduating from Cresson High, the young ballplayer turned pro. Jim Gionfriddo recalls that a scout for the Pittsburgh Pirates, whose name he does not remember, discovered Al when their Legion team played against Reading’s Legion team. This was probably in August 1940, when Cresson was one of four teams that made it to the Legion’s Pennsylvania state tournament, representing the West Central region. The scout was quite likely Patsy O’Rourke, a Philadelphian who also frequented Reading.

“His father felt he should have been working, but it was a dream come true for Al,” says Sue. “It was also a ticket out of the mines. He spent some time there, maybe a summer.” Gionfriddo said in 1972, “I worked in the coal mines, and I didn’t like that. I signed for $65 a month and the love of baseball. I just wanted to get into baseball.”1

Al joined the Oil City Oilers, the Pirates’ farm club in the Pennsylvania State Association (Class D). He enjoyed a strong season, batting .334 with 7 homers and 58 RBIs. He followed that by making the circuit’s all-star team for Oil City in 1942 (.348-11-82). Like another diminutive Italian, Phil Rizzuto, Gionfriddo was just 5’6” and roughly 160 pounds — but he could run. “The Dysart Deer,” who had also been a sprinter in high school, scored 112 times to lead the league. Already he was developing a reputation for sensational catches too.2

With World War II in full swing, however, Al was ordered to report to his draft board that August. He joined the Army on February 9, 1943. He was stationed at Camp Howze, near Gainesville, Texas, one of the largest infantry replacement training centers in the country. Gionfriddo was a private with Battery C of the 331st Field Artillery.3

Al only had to spend a little less than a year in the military, though — he received a medical discharge on January 15, 1944. “He was running the obstacle course, which he did very well,” Sue observes. “His commanding officer had some kind of bet and wanted him to do it again, but Al ruptured his stomach. After he was discharged, he went back to school and finished up.”

Gionfriddo then resumed his baseball career with Albany in the Eastern League (Class A). Noted for his hustle and “one of the most aggressive spirits in baseball,” he played every inning of every game that season.4 In addition to his basic batting line of .329-1-78, Al once again led his league in runs scored with 130 as well as walks (108). He was also tops in stolen bases with 51. What’s more, his 28 triples are still the Eastern League’s single-season record.

On May 22, 1944, Al and Arlene Lentz — a childhood sweetheart from Cresson5 — got married in Albany. After the minor-league season ended, the Pirates called up the outfielder, and he made his debut at the Polo Grounds on September 23. Giants reliever Ace Adams retired Al, who was pinch-hitting for Preacher Roe. Gionfriddo went 1 for 6 in four games. His first hit, a single, came on September 27 off Al Javery of Boston at Braves Field.

In 1945, Gionfriddo enjoyed his only season as a big-league regular. Jim Russell and Johnny Barrett were the other primary outfielders, but starting third baseman Bob Elliott saw duty in 61 games at his original position too. In 122 games with Pittsburgh, Al hit .284 with 2 homers and 42 RBIs. The homers, off Lee Pfund on May 30 and Red Barrett on August 5, were the only ones he ever hit in the majors. In July, the Cresson draft board recalled the “pride of the Pittsburgh bobby-soxers” (his smile was always broad and gleaming). However, he got an extension, since Arlene was expecting their first child, Susan. Meanwhile, the war ended.6

Al had made The Sporting News all-rookie team in 1945, but the next year, he ceded time to a new star who had returned from service in the Navy Air Corps. Rookie Ralph Kiner led the NL in home runs for the first of seven consecutive seasons. Gionfriddo played in just 64 games with 102 at-bats (.255-0-10). In late August, he underwent an appendectomy in Pittsburgh, and that was it for his season.7 After he recovered, though, Al returned in October to play with a group of touring major-leaguers skippered by Pirates coach Honus Wagner. The opponents were an African-American squad headed by Jackie Robinson, who would become Gionfriddo’s teammate the next year.8

Gionfriddo’s most intriguing baseball activity in ’46 came off the field. He was involved in the Pirates’ strike vote that June, the key to a failed bid to organize baseball’s labor movement two decades before Marvin Miller’s arrival.9 In fact, Al wondered whether his activism might have been held against him when he was later buried in the minors.10

Gionfriddo’s most intriguing baseball activity in ’46 came off the field. He was involved in the Pirates’ strike vote that June, the key to a failed bid to organize baseball’s labor movement two decades before Marvin Miller’s arrival.9 In fact, Al wondered whether his activism might have been held against him when he was later buried in the minors.10

After working in the offseason as a fireman on the Pennsylvania Railroad, “G.I.” came to the plate just once for the Pirates early in 1947. Then on May 3, he was sent to the Brooklyn Dodgers along with at least $100,000 — possibly as much as $300,000 (reports varied). The Dodgers unloaded Kirby Higbe — whose refusal to play alongside Robinson prompted the trade — along with Hank Behrman, Cal McLish, Gene Mauch, and Dixie Howell. Legend has it that Gionfriddo carried the cash in a satchel.

“Al was slightly miffed when he heard the news that he was sold to Flatbush, as he was just building up a tire business in Pittsburgh, and remained unhappy even after he was assured that he would stick”11 even though Brooklyn had many outfielders already. Indeed, rather than going to Triple-A, he stayed as a backup, batting .175-0-6 in 63 games. Despite his small role on the field — manager Burt Shotton knew him mainly as “the little Italian” — he had a subtle influence in the clubhouse. In 2007, journalist John Zant (who knew Al for many years) recalled an anecdote he’d heard first 20 years before:

“Gionfriddo told me he had felt a kinship with Jackie Robinson. The first black major leaguer in the modern era endured scorn not only from opponents but from some of his own teammates. He would not go into the showers until everybody else was done, Gionfriddo said, until one day he went up to Robinson and said, ‘Jackie, what are you waiting on? I’m not accepted any more than you are, but we’re part of this team. Let’s go.’”12

Ten years previously, in a chat with Mike Downey of the Los Angeles Times, Al had noted, “I made sure Robinson had the locker right next to mine.”13 It was also in 1997 that Al appeared on the ESPN show “Outside the Lines” to discuss how the Pirates and other National League teams voted on whether to strike if Jackie set foot on the field.

“Al was disappointed by the trade at first,” Sue Gionfriddo confirms. “But a bad thing turned into a good thing. He got the opportunity to be part of history, and he cherished it.” That chance came because the Dodgers won the National League pennant in ’47 and faced the New York Yankees in the World Series.

The Fall Classic came to television for the first time that year, though it was carried in only four markets: New York City; Philadelphia; Washington, DC; and Schenectady (!). Bars benefited greatly, but the action prompted many residential TV purchases too.14 NBC showed Games 1 and 5, CBS got Games 3 and 4, and the long-gone Dumont Network had the rights to Games 2, 6, and 7.

Gionfriddo’s postseason debut came in Game Two; he made the last out as a pinch-hitter. His next appearance remains one of the most storied battles in Series history — the near no-hitter by Bill Bevens in Game Four at Ebbets Field. With two out in the ninth, Shotton sent Al in to pinch-run for Carl Furillo, who had drawn Bevens’ ninth walk of the day. The count went to 2-1 on pinch-hitter Pete Reiser. Shotton then gambled — he wasn’t just trying to avoid the no-hitter, he was looking to tie or win the game.

Al recalled to Mike Downey, “I looked over and there was Ray Blades in the coaching box, giving me the steal sign. I couldn’t believe my eyes. If I get thrown out, the game’s over.”15

At the time, he told The Sporting News what happened as he lit out. “I started for second and slipped on the first step. I thought I was a dead duck. To make up for my slipping I didn’t slide feet first. I made a headlong dive for the bag. But I still think any kind of throw would have had me.”16

A furious Phil Rizzuto still thought he’d gotten Yogi Berra’s bad throw down in time. Nonetheless, Gionfriddo was safe. Yankees manager Bucky Harris then made his controversial decision to intentionally walk the gimpy Reiser, who was gutting it out on a taped broken ankle. Al noted, “Pete’s leg hurt so bad, if he’d hit one off the fence, I honestly don’t know if he could have run to first base.”17 Eddie Miksis ran for Reiser, and then Cookie Lavagetto ended the no-hitter and the game with his pinch-hit double.

In Game Five, Gionfriddo drew a pinch-hit walk and scored Brooklyn’s only run in a 2-1 loss. Then it was back to Yankee Stadium.

Game Six drew a crowd of 74,065 — a World Series record at the time. The Dodgers led the Yankees 8-5 going into the bottom of the sixth inning when Al was brought in to replace Miksis in left field. Normally an infielder, Miksis had himself gone in for Gene Hermanski. A “wobbly” Joe Hatten (as Red Barber later described him) had walked Snuffy Stirnweiss after a sharp lineout; Tommy Henrich barely missed a homer before fouling out; Yogi Berra singled.

Then Barber, calling the game on the Mutual radio network, set the scene for the moment that would last for the rest of Al Gionfriddo’s life and beyond:

“Joe DiMaggio up, holding that club down at the end. Big fellow sets, Hatten pitches — a curveball, high outside for ball one. Sooo, the Dodgers are ahead, 8-5. And the crowd well knows that with one swing of his bat this fellow’s capable of making it a brand-new game again. Outfield deep, around toward left, the infield overshifted. Here’s the pitch, swung on — belted! It’s a long one deep into left center — back goes Gionfriddo! Back- back-back-back-back-back. . .he makes a one-handed catch against the bullpen! Ohhh-hooo, Doctor!”

“‘Don’t write this in the paper,’ [Dimaggio] told a group of reporters, ‘but the truth is that if he had been playing me right, he would have made it look easy.’”18 Gionfriddo himself would later admit that he was playing shallow, and a couple of steps overshifted to left, at the direction of coach Clyde Sukeforth.19 This heightened the drama of his sprint. He would describe the play many times over the years; perhaps the most vivid account in his own words appears in the book The Era 1947-1957 by Dodgers chronicler Roger Kahn.

“‘At Yankee Stadium, the left field bullpen, where the visiting relief pitchers warmed up, there were these gates that the relief pitchers walked through when they went in to pitch. The gates were metal, with an iron frame. Something between three and four feet high.

‘I picked up DiMaggio’s ball good. He hit it high and deep toward those iron gates. I didn’t think I had a chance. I’m maybe three hundred forty, three hundred fifty feet out. Next to those gates, there’s a sign, big capital letters. It says, 415 FT.

‘I put my head down and I ran, my back was toward home plate and you know I had it right. I had the ball sighted just right.’ After all these years, Gionfriddo laughs in gorgeous triumph.

‘The ball is going at the bullpen gate and I look over my left shoulder. My back is to the plate. Over my left shoulder. I am left-handed. I throw left. So the glove is on my right hand. I see the ball coming and as the ball is coming in, I make a jump.

‘Since I am left-handed I have to reach my glove, which is on my right hand, over my left shoulder. I do that. I jump and make the reach.

‘I’m turning in midair. I’m turning and reaching and I catch the ball. I crash the gate. I hit it hard, against my right hip. I hold the ball.’”20

DiMaggio became more gracious about the play, as Al recalled to Kahn. The pair addressed a group of children some years later, and Joe said, “Some big guy wouldn’t have ever made the Catch. A big guy woulda backed off and left it to go over the fence. But this little guy. He always had to work harder than anybody else. . .he never gave up.”21 He and Al also got together in 1974 to offer their recollections of the 1947 Series for the TV program “The Way It Was.”22

Though most stories at the time said the ball would have been a home run, debate still stirs today. Even back then it was not unanimous. Associated Press writer Frank Eck noted, “there were many in the [Yankee] dressing room who believed the ball would have hit the iron fence for at least a triple.”23 DiMaggio biographer David Jones quoted historian Eric Enders: “This was merely an example of the halo granted DiMaggio by the New York media. Film of the play clearly shows that it would not have left the park. Indeed, Gionfriddo caught the ball two full steps in front of the fence.”24 25

Al himself always thought he stopped it from going out, his wife states. At the time, he told The Sporting News, “Bobby Bragan was in the bullpen, and he said it would have cleared the fence by from one to two feet.”26 On the radio, Red Barber (who was not given to hyperbole) said, “He took a home run away from DiMaggio.”

The visual evidence is patchy and open to question. The existing newsreel footage does not show the play from start to finish, and there are even allegations it may be a staged re-enactment. However, an expert in the field dismisses this idea. Doak Ewing, proprietor of Rare Sportsfilms, Inc., says, “Anybody who thinks that doesn’t know film. There are a couple of different views out there, with different angles, but how could you stage that crowd?” Sue Gionfriddo adds, “Al had been asked, and he felt that the newsreel footage was accurate. It was always his understanding that it was live.”

Along with the fans’ reaction, reality shows in the way #30 loses his cap on the run and then gets it back from the center fielder (though one cannot make out Carl Furillo’s distinctive profile). One may also see the left-field umpire — another first from the ’47 Series — enter the frame to give the “out” sign. Alas, ump Jim Boyer passed away in 1959, and his view is not known.

Decades later, other authors have drawn and fostered (mis)impressions from this clip. For example, another DiMaggio biographer, Richard Ben Cramer, describes Al as “dancing a spirited tarantella, unsure where to run, which way to turn, how to get under the ball.”27 Jonathan Eig called it a “stumbling, bumbling play.”28 These descriptions belie Gionfriddo’s skill as an outfielder — and many other contemporaneous accounts besides Al’s. For one, Hall of Famer Bill Terry called it “the greatest catch I’ve ever seen.”29

Photographers got Pee Wee Reese to pose kissing Al on the cheek, though “finally Reese, grinning as happily as all the other Dodgers, pretended annoyance and called out: ‘Let somebody else kiss this little guy. I’m tired of it.’”30 The jubilance faded the next day, though, as Brooklyn lost Game Seven; Al did not get to play. Still, on October 12, Dysart declared “Al Gionfriddo Day.” A crowd of 5,000 people from Cambria, Centre, and Blair counties gathered to greet the local hero, who played center field as Dysart defeated Coalport in an exhibition game.31

Gionfriddo went to spring training in the Dominican Republic with the Dodgers in 1948. On April 14, though, Brooklyn sent him outright to their top farm club, the Montreal Royals of the International League. The Associated Press noted that the club was making room for pitchers Dwain Sloat and John Hall. However, Brooklyn’s outfield was just too crowded. Gene Hermanski, Carl Furillo, and Marv Rackley received the bulk of the playing time, but second-year man Duke Snider started to see more action. The key reserves that year were George Shuba and Dick Whitman, while veterans Pete Reiser (in his last season as a Dodger) and Arky Vaughan (who would retire after ’48) were still on the scene.

Al accepted the assignment without complaint, in part because he was still receiving his major-league salary. Manager Clay Hopper said, “There’s my leadoff man.”32 The fireplug then displayed power that he had never shown before (and never would again). He hit 25 homers, drove in 79, and batted .294, although he was hampered late in the season by a shoulder injury sustained in making a difficult catch.33

Gionfriddo’s obituary in The New York Times says, “He remained bitter toward Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ general manager. Gionfriddo maintained that Rickey reneged on a promise to bring him back to the majors, leaving him 60 days short of qualifying for a pension.”34 However, his wife’s recollection differs somewhat. “Pension was an issue,” says Sue. “He and a lot of other old-timers were not treated fairly. But by the time I knew him, he’d mellowed. There weren’t hard feelings.”

After the season ended in Montreal, Al went to play winter ball in Cuba along with several other Dodger farmhands, including future TV star Chuck Connors, Sam Jethroe, and Clyde King. They joined the Almendares club, which had lost star outfielder Roberto Ortiz to suspension for jumping to the Mexican League. Cuban baseball author Roberto González Echevarría thought that “if Ortiz, rather than Gionfriddo, had played in the 1948-49 Almendares outfield with [Sam] Jethroe and [Monte] Irvin, [Mike] Guerra’s team would have waltzed to the pennant.”35

Nonetheless, the Alacranes (Scorpions) still beat Habana by eight games, and Al enjoyed a fine season. In 64 games, his .308 average was good for fifth in the league, and he had 1 homer and 35 RBIs, along with 13 steals. Almendares represented Cuba in the first Caribbean Series in February 1949. As Cuba went 6-0, Al led all batters, going 8 for 15 (.533) with three doubles and eight runs scored.

However, he still faced a logjam in Brooklyn in 1949. Duke Snider had locked up center field, and Carl Furillo moved to right. Along with Gene Hermanski, the other outfielders were Mike McCormick and (returning from suspension) Luis Olmo. So Gionfriddo returned to Montreal, and his output lessened (.251-9-62). In general, though, Sue Gionfriddo says, “He loved playing there — those were good times. We went back in around 1973 or ’74, when the Canadian Italian Business and Professional Men’s Association honored him. We went back again for an old-timers’ event in the ’90s.”

In the winter of 1949-50, Al came back to Almendares (.258-3-23 in 60 games). The Blues (an alternate nickname) again represented Cuba in the Caribbean Series, but the “runaway favorites” went just 3-3 as Panama staged an upset. In a reversal from the previous year’s series, Gionfriddo went 0 for 16.

Sue notes, “Al had good experiences in Cuba too. The players lived well, and the fans were intense. Many years later, we went to Florida to play at the Doral Golf Club. Our waiter was a member of the Cuban community there, and when he recognized the name as Al signed the check, he broke down and cried at the memories it brought back.”

Gionfriddo played two more seasons with the Royals. His average rebounded in 1950 (.310-5-41), but the Dodgers had brought in a former Pirates teammate, veteran Jim Russell. It appears that Al did not return to Cuba or any other winter-ball league in 1950-51. The following summer, he showed a bit more pop (.269-9-56), but Andy Pafko occupied left field in Brooklyn after a trade with the Cubs. Hermanski was still around, as was Cal Abrams, and then younger prospect Dick Williams won a roster spot. To get an idea of the “dog-eat-dog” competition, George Shuba was also stuck in Montreal in 1951.

Between the 1951 and 1952 seasons, Gionfriddo was transferred to Brooklyn’s other top farm club, St. Paul. Royals manager Walter Alston was sorry to see him go, commenting that he and a few other transfers “weren’t the flashy type, but were good steady performers who always gave their best and their spirit was a real asset in our success.”36

However, Al “didn’t want any part of” St. Paul. In 1987, he said, “It’s a dirty game. They can do what they want with your life. At least they could back then. We didn’t have agents and lawyers then. The players now make demands. We begged.”37 On April 1, Al was named player-coach-road secretary of the Fort Worth Cats, the Dodgers’ Double-A affiliate in the Texas League.38 He saw only part-time duty, and he also started the season late because of a back injury. His batting suffered (.221-0-16).

In 1953, Gionfriddo became manager of Drummondville in Canada’s Provincial League. Although not formally affiliated with any big-league club, the Royals had a working agreement with the Dodgers.39 Al remained an active player too, batting .245 with 4 homers and 30 RBIs. In 1954, though, he recalled that “Drummondville was having trouble meeting expenses and was glad to see the higher salaried players go.”40 He was released on July 25.

Gionfriddo then moved on to Newport News in the Piedmont League (Class B). Despite performing reasonably well (.315-1-11), the Dodgers organization released the 32-year-old at the end of the season. It was a difficult stretch for Al, as his mother Rose had passed away that August.

“Al moved with the wife and three children from Altoona, Pa., to Van Nuys, Calif., and figured he might as well give up baseball. But Chuck Connors talked him into staying in the game.”41 In 1954, the “greying little ballhawk” joined Channel Cities in the California League (Class C). The unaffiliated club represented Ventura and Santa Barbara. Under manager Dario Lodigiani, the former Philadelphia Athletic, Al hit .332 with 8 homers and 69 RBIs. He noted, “This is a great little league, but. . .we go around in three station wagons and the other night I had to walk two miles to find a filling station after we ran out of gas.”42

Gionfriddo stayed in the California League for his last two pro seasons, playing with the Visalia Cubs (unaffiliated, despite the name). His .368 average in 1955 was .002 behind the batting champ, future big-leaguer Bobby Gene Smith, who went 4 for 4 on the season’s last day. With 8 homers and 96 RBIs, Al was still good enough to be a league all-star. In 1956, he posted another nice set of stats (.354-9-73) but then chose to retire at age 35.

After his playing days ended, Al remained in California. A man named Jack Wood, who worked nights at the Tulare County Juvenile Hall in Visalia, remembers what the ex-ballplayer did to support his family. “One night a new man showed up for work at the Juvenile Hall. It was Gionfriddo. His baseball career was over. He worked two eight-hour shifts — one at the Hall, the other at the Tulare County Boy’s Camp. He had to. He had a wife and a houseful of kids to support and feed.”43

Al then became an insurance salesman in Visalia. He also managed a Little League team, served as president of the local Babe Ruth League, and ran schools for Little League managers. In November 1960, he said, “Baseball, and athletics in general, makes a better man of you. I always tell [the kids] to get a college education first. That’s more important than making the big leagues.”44

He renewed his involvement with pro baseball at the end of that year, though, as the San Francisco Giants added him to their scouting staff. “His territory will be central California — the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys and adjacent interior areas.”45 As a Giants scout in 1961, Al signed at least one promising prospect, a shortstop named Russ Vanderziel, but Vanderziel’s pro career stalled in the low minors.

In 1962, baseball returned to Santa Barbara after an absence of eight years, and Gionfriddo became general manager of the Rancheros, which were then a Mets farm club. The next year the franchise joined the Dodgers chain and took the new big club’s name. Al was general manager through 1964. Sue remembers that “the Dodgers wanted him to move, and he didn’t want to go. Tommy Lasorda went instead.” The job Lasorda took in 1965, with the Pocatello Chiefs in the Pioneer League (rookie ball), was the first step in his long career as a manager.

After that, Gionfriddo went into the restaurant business. He was manager of a place called Petrini’s, on a side street in Goleta, a Santa Barbara suburb. “It was an oyster bar,” says John Petrini, one of the three brothers who founded the original long-running Petrini’s in Santa Barbara. “Then a few years later he bought it and renamed it Al’s Dugout.” It was a modest café with red and white checkered tablecloths. The walls were loaded with baseball pictures, most notably a blowup of the Catch. Gionfriddo, who also served as cook, said, “Working people eat here. The same people who are the backbone of sports. The people who have to save their dollars to go to a game.”46

Al and Arlene divorced in Santa Barbara in March 1971. On July 22, 1973, Al got married to Sue, whom he had met five years before — she played first base for the women’s team he’d organized for Petrini’s. Sue eventually became Chief Probation Officer for Santa Barbara County. She also served as president of the Chief Probation Officers of California.

In 1974, Gionfriddo sold the restaurant. He then became an athletic equipment manager and trainer at San Marcos High in Santa Barbara. There he remained for 15 years before retiring in 1988. In October 1977, 30 years after the Catch, the Associated Press noted that he was serving as a part-time scout for the Cincinnati Reds.47 “He was bird-dogging for at least a couple of years for the Reds, maybe three,” Sue recalls. “It was a local thing, he didn’t get out on the road. Cincinnati had a tryout camp in Santa Barbara and Al would help.”

Al kept active tying handmade fishing lures48 and also as a marshal two days a week at the Sandpiper Golf Course in Goleta.49 “He loved golf,” says Sue. “He played several times a week. He got into it while he was a player. He had a single-digit handicap when he was younger, and it hovered between 10 and 12 in later years. He won his local senior club championships.”

In 1995, the Gionfriddos moved to the quaint Danish village of Solvang, a little over 30 miles northwest of Santa Barbara in the Santa Ynez Valley. There they settled in a home with ducks and geese in the yard, a hand-carved signpost joking that “A Nice Person And A Grouch Live Here,” and a doorbell chiming “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.”50

Al continued to believe that ballplayers of his generation had been denied justice. In July 1996, he joined four other former major-leaguers — Seymour Block, Pete Coscarart, Dolph Camilli, and Frank Crosetti — in filing a class action suit against Major League Baseball. Block’s suit was filed in Alameda Superior Court, but Al also brought separate action in San Francisco Superior Court. The group contended that MLB’s commercial use of “their names, voices, signatures, photographs and/or likenesses” violated their rights of publicity under California common law and the California right of publicity statute. One key point was that the men had played before 1947, when the standard player contract was amended. Players then gave up their publicity rights to the clubs.

In 2001, however, the state’s Court of Appeal affirmed earlier decisions on Gionfriddo v. Major League Baseball. First, class action status was denied, and thus the hope disappeared that up to 800 other veterans might benefit. Then, as the men proceeded on their own, both their common law and statutory claims were dismissed.

“Al was very disappointed,” says his wife. “He was passionate about his beliefs. The old guys were cut out, he said — they were part of the history, but not part of the solution. I remember Pete Coscarart telling Al, ‘You know, they’re just going to wait for us to die. Then it’ll go away.’”

Six days after his 81st birthday, on March 14, 2003, Al was enjoying his favorite pastime — a round of golf on one of the two courses at beautiful Alisal Guest Ranch in Solvang. On the fifth green at the private course, Alisal Ranch, he was stricken by a fatal heart attack.

“There were no pre-existing health issues,” Sue notes. “He’d just had a thorough cardio workup and everything was fine. In fact, the day before he shot a 76. He hadn’t been feeling well that morning, but he was out there again — ‘maybe I’ll shoot a 75 today,’ he said. His friends suggested he use the cart, but he didn’t want to. He missed his birdie putt, made par, and then it came. It was massive and sudden. His friends tried to revive him, but they couldn’t.”

Former Dodgers manager Tom Lasorda, who had been Al’s roommate in Montreal, commented, “He was an outstanding ballplayer and friend. He wore the Dodger uniform proudly, and we’re losing a great Dodger.”51

Gionfriddo was survived by four of his six children with Arlene: Susan, Gary, Alene, and Ray. Two other children, son Robert and daughter Kris, predeceased him—Robert on August 10, 1983, and Kris on November 5, 1995. Ray died unexpectedly almost a year after his father. Al also had 14 grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren — not to mention three pet beagles. “Al was crazy about them — they are members of the family,” says Sue.

Al Gionfriddo is buried in Santa Barbara Cemetery. His headstone bears an inscription of a crossed baseball bat and golf club. Yet he will always be associated with his “thrill of a lifetime” feat from October 1947. “I’ve signed thousands of that picture,” Al remarked in 2000.52 In 1991, he said, “You think, ‘Geez, how in the world do these people remember?’ They were there when they were teen-agers, I guess, and they tell their sons, their grandkids.”53 Hollywood portrayed this very thing in a tender deathbed scene from the 1989 film Dad with Jack Lemmon and Ted Danson.

Sue adds, “He used to say, ‘If all the people that said they were there that day actually were there, Yankee Stadium must have held a million.’ But he was very humble about it. He would never bring it up, but he was very willing to entertain real fans, people who were well-versed.”

“He lit up around people. The autograph shows and reunions were an opportunity to see his old teammates and friends, but a lot of people felt he was a friend to them. Al said, ‘We played baseball because the fans were willing to pay to see us play.’ He always felt he owed it back to the fans to continue to entertain them.”

Grateful acknowledgment to Sue Gionfriddo and the Gionfriddo family for their memories. Thanks also to John Petrini, John Zant, and SABR member Doak Ewing.

Sources

Philip Roth quote: Portnoy’s Complaint.

http://www.ancestry.com: 1910, 1920, and 1930 census data. Note that the name of Gionfriddo was misspelled each time — as Geofrrido, Goifriddo, and Gomfredo. This source also provided Al’s wedding dates and Paul Gionfriddo’s place of birth (from military records).

Professional Baseball Players Database V6.0

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. 2nd ed. Durham, NC: Baseball America, Inc., 1997.

Figueredo, Jorge S. Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2003.

Figueredo, Jorge S. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball 1878-1961. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2007.

http://www.retrosheet.org

SABR Home Run Log, http://www.sabr.org

Charney, Frank, “Sunday Postcard,” May 18, 2003 (http://www.nantyglo.com/postcards03/may1803.htm)

Frommer, Harvey. New York City Baseball: The Last Golden Age. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004.

Barber, Red. 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball. New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1984.

Gionfriddo v. Major League Baseball, 94 Cal.App.4th 400, 114 Cal.Rptr.2d 307 (2001).

http://www.law.com/regionals/ca/opinions/dec/a091113.shtml

http://bob.sabrwebs.com/content/docs/court_cases/Gionfriddo.pdf

http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/data2/californiastatecases/a078967.doc

Burr, Harold C. “Rickey Solves Squad-Cutting Worry by Jackpot Deal That Nets $200,000”. The Sporting News, May 14, 1947: 6.

Daley, Arthur. “The Impossible Is Still Happening”. The New York Times, October 6, 1947, p. 29.

“Gionfriddo Got Thrill of Lifetime Making Catch”. Brooklyn Eagle, October 6, 1947.

Links to audiovisual records of the Catch:

Red Barber’s radio call: http://www.thedeadballera.com/Audio/Gionfriddo.mp3

Pathé News newsreel clip: http://www.spokane7.com/blog/2009/sep/02/halberstam-had-a-way-with-words/

Photo Credit

Gionfriddo’s catch: Swell Gum

Notes

1 Distel, Dave. “Moment of Glory.” The Los Angeles Times, November 2, 1972: C2.

2 Szafran, Joe. “Scanning the Field.” The Oil City (PA) Blizzard, May 26, 1942: 11.

3 “From Service Front.” The Sporting News, May 6, 1943, p. 8. See also Bedingfield, Gary: Baseball in Wartime (http://www.garybed.co.uk/player_biographies/gionfriddo_al.htm)

4 Whoric, John H. “Sportorials: Bits Here and There.” The Daily Courier (Connellsville, PA), August 8, 1945: 9.

5 The Sporting News, June 1, 1944: 24.

6 Lieb, Frederick G. “Strongest All-Freshman Team Since ’41 Named.” The Sporting News, November 1, 1945: 7.

7 Doyle, Charles J. “Crippled Bucs Hear the Door Slam on Cellar.” The Sporting News, September 4, 1946: 10.

8 “Robinson’s Stars Split in Opener.” The Sporting News, October 16, 1946: 23.

9 For general discussion of this strike vote, see Rossi, John. A Whole New Game: Off the Field Changes in Baseball, 1946-1960. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1999: 10-11.

10 Gustkey, Earl. “1947: A Series of Surprising Stars — Lavagetto, Bevens and Gionfriddo Had Their Moments .” The Los Angeles Times, October 17, 1987.

11 Ruhl, Oscar. “From the Ruhl Book.” The Sporting News, October 15, 1947: 22.

12 Zant, John. “The Catch Heard ’Round the World: Remembering the Day Al Gionfriddo Made Joe DiMaggio Angry, 60 Years Later .” The Santa Barbara Independent, October 4, 2007.

13 Downey, Mike. “A Fall Classic.” The Los Angeles Times. August 27, 1997. C1.

14 Walker, James R. and Bellamy, Jr., Robert V. Center Field Shot: A History of Baseball on Television. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008: 68. (http://centerfieldshot.com/4)

15 Downey, op. cit.

16 Birtwell, Roger. “The Inside Story of an Inning That Hit the Peak of Drama.” The Sporting News, October 15, 1947: 9.

17 Downey, op. cit.

18 Halberstam, David. Summer of ’49. New York, NY: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2002: 49. David Halberstam, age 13, was in the stands at Yankee Stadium that day. See Zant, John. “Gionfriddo’s Catch Receives the Stamp of Authority.” Santa Barbara Newsroom, May 11, 2007.

19 Anderson, Dave. “Subway Series Reflections: A Ride on the Carousel of Time.” The New York Times, October 20, 2000.

20 Kahn, Roger. The Era, 1947-1957: When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002: 127.

21 Ibid., p. 128.

22 Weichel, Penny. “Gionfriddo Revisited .” The Derrick (Oil City, PA), November 16, 1974: 10.

23 Eck, Frank. “DiMag’s Blow Called Longest He Ever Hit.” The Titusville (PA) Herald, October 6, 1947: 8.

24 Jones, David. Joe Dimaggio. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004: 97-98.

25 Enders, Eric.100 Years of the World Series. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2003: 118.

26 Birtwell, Roger. “Little Al Didn’t Expect to Stay With Dodgers.” The Sporting News, October 15, 1947: 19.

27 Cramer, Richard Ben. Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2000: 235.

28 Eig, Jonathan. Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007: 257.

29 “‘Greatest Catch I’ve Ever Seen’–Terry .” Winnipeg Free Press, October 6, 1947: 14.

30 McGowen, Roscoe. “Outfielder Feted for Mighty Catch.” The New York Times. October 6, 1947: 28.

31 “Gionfriddo Is Honored; Brooklyn Hero Feted in Home Town — Stars in Ball Game.” The New York Times, October 13, 1947: 35.

32 McGowan, Lloyd. “Al Gionfriddo, Demoted Series Star, Socking Instead of Sulking as Royal.” The Sporting News, June 23 1948: 19.

33 Short, Phil. “Short’s Sports .” The Daily News (Huntingdon and Mount Union, PA), August 25, 1948: 4.

34 Goldstein, Richard. “Al Gionfriddo, 81; Remembered for ’47 Catch.” The New York Times, March 16, 2003.

35 González Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999: 68.

36 McGowan, Lloyd. “Alston Faces Big Rebuilding Job as Royals Start Drills.” The Sporting News, March 19, 1952: 24.

37 Gustkey, op. cit.

38 The Sporting News, April 9, 1952: 28.

39 Baillie, Scott. “Happy Once Again: Al Gionfriddo Now Playing for Ventura.” The Daily Review (Hayward, CA), May 20, 1954: 10.

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Wood, Jack. “Al Gionfriddo and Joe Dimaggio ,” http://nyenevada.blogspot.com/2008/04/al-gionfriddo-and-joe-dimaggio.html, April 26, 2008.

44 Ledbetter, Steve. “Brief Series Hero Gionfriddo Sells Insurance and Baseball.” Titusville (Pennsylvania) Herald, November 11, 1960: 6.

45 McDonald, Jack. “Giants May Call Kid Whizzers to Early Camp.” The Sporting News, December 28, 1960: 12.

46 Distel, op. cit.

47 Clarke, Norm. “Gionfriddo’s Impossible Catch Ranks Among Series Legends.” The Press-Courier (Oxnard, California), October 16, 1977: 25.

48 Kahn, op. cit.: 115.

49 Downey, op. cit.

50 Ibid.

51 “Al Gionfriddo, 81; Dodger Made Game-Saving Catch in ’47 Series.” The Los Angeles Times, March 16, 2003: B14.

52 Anderson, op. cit.

53 Campbell, Steve. “Gionfriddo’s name still catchy over 40 years later.” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 11, 1991: 9.

Full Name

Albert Francis Gionfriddo

Born

March 8, 1922 at Dysart, PA (USA)

Died

March 14, 2003 at Solvang, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.