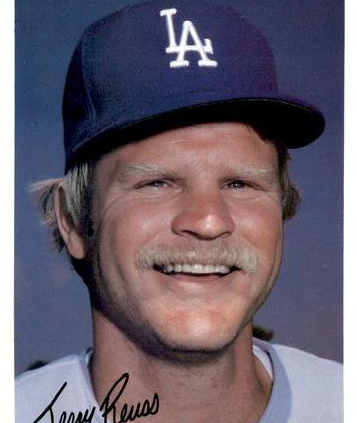

Jerry Reuss

Born June 19, 1949, in St. Louis and then raised there, Jerry Reuss made his major league debut for the team he cheered on as a child; and then was traded by that team because the owner didn’t like his mustache. At his next stop he was considered “the asshole of all time1” by his Hall of Fame manager. From there he had Opening Day starts for three different clubs, started the 1975 All-Star Game, threw a no hitter against his fourth team’s biggest rival, was winning pitcher in the 1980 All-Star Game, earned a 1981 World Series ring which he still wears nearly every day, won more than 200 games, and was released five times.

Born June 19, 1949, in St. Louis and then raised there, Jerry Reuss made his major league debut for the team he cheered on as a child; and then was traded by that team because the owner didn’t like his mustache. At his next stop he was considered “the asshole of all time1” by his Hall of Fame manager. From there he had Opening Day starts for three different clubs, started the 1975 All-Star Game, threw a no hitter against his fourth team’s biggest rival, was winning pitcher in the 1980 All-Star Game, earned a 1981 World Series ring which he still wears nearly every day, won more than 200 games, and was released five times.

“My grandpa on my mother’s side, Alfred Hellwig, was the big baseball fan,” said Reuss, when asked how his baseball odyssey began. “He would ride the streetcar to Sportsman’s Park to see both the Browns and the Cardinals almost every afternoon.”

Jerry was the middle boy of three sons. His father Melvin drove a bread truck, worked for Royal Crown Cola and managed a paint store while Jerry and his brothers Jim and John were growing up; his mother Viola sold real estate and worked as an interior designer. Both parents are deceased. Jim, the older brother, is now retired from a career in the Houston Parks System and works part time managing the city’s municipal golf courses. “I think that’s so he can play when and where he wants. Jim loves golf,” said Jerry. His younger brother John works as the assistant manager at a suburban Walgreen’s store near St. Charles, Missouri.

Like most big leaguers, Reuss dominated in youth baseball. “There weren’t many lefties, I was bigger than most kids and I could throw hard from the time I was about 10,” he remembered. “I was always able to compete against kids who were two to three years older. By the time I was a freshman in high school [Ritenour in St. Louis] I could compete against seniors. While I was there my high school baseball team won two state championships and my American Legion teams always went a long way.” Ritenour had the advantage, Reuss said, of drawing from a large area. His graduating class had about 1,000 students.

One of Reuss’s high school teammates was the son of Cardinals farm director George Silvey. That connection paid off for Reuss when his hometown team made him its second-round choice in the 1967 amateur draft. “I was surprised,” Reuss said. “The Cardinals were in the background. Naturally I was thrilled to be drafted by my favorite team.” Reuss still fondly recalls his first trip to the old Busch Stadium. “I remember everything, the smells, the dark tunnel, the green grass, the pavilion roof, the white warning track, the Cardinals’ red and white uniforms, and the perfect weather that day. I felt like the stadium ramp was a ramp to heaven.”

Reuss signed for a $32,500 bonus and was dispatched to the Cardinals Gulf Coast Rookie League team to begin his professional career. After pitching seven innings in Florida and surrendering four earned runs he was moved to Cedar Rapids of the Midwest League. Despite a 2-5 record, Reuss delivered an ERA of 1.86 in 58 innings with a WHIP barely over 1.00. That earned him an inning in AAA at the end of the season in which he gave up six runs to players much older and much more experienced. Reuss spent the entire 1968 season in AA ball with Little Rock, where he again delivered an excellent ERA [2.17] and WHIP [1.071] and a crummy win-loss record [7-8]. Still, it was apparent by then that Reuss was on the fast track to St. Louis.

“I thought from the time I signed that I would be a major league pitcher,” Reuss said as he looked back on his career in March of 2011. “There were a lot of talented guys, but I stuck with it, worked hard, and advanced quickly.” Being six feet, five inches tall and left-handed didn’t hurt his prospects either.

A striking thing about Reuss’s minor league career is the low number of games he pitched each season. In 1967 Reuss appeared in a total of 12 games for the three teams, and in 1968 he appeared in just 17 for Little Rock. The explanation has a lot to do with the Viet Nam-era machinations common during that time. “I enrolled in Southern Illinois University to maintain my student draft deferment. That would force me to miss spring training, except for a week during spring break, start the season a few weeks late and miss the last few weeks to start classes in the fall,” he explained. “Fortunately, I was able to complete my military reserve obligations while attending school during the winter.”

Reuss said he was lucky in that he was allowed to pitch batting practice to the Southern Illinois baseball team while in school. He says this kept him sharp and helped mitigate his need for full spring training. It would have been much tougher to throw BP using dead grenades while living in a foxhole.

The 1969 season saw Reuss advance to AAA with Tulsa. His performance as a 20-year-old in AAA was not what it was for Little Rock in 1968, but his 13-11/4.06/1.634 line with 151 strikeouts in 186 innings was enough to earn him a September call up to St. Louis. “Expansion helped me,” Reuss said, referring to the San Diego Padres and Montreal Expos entering the National League in 1969. “The Cardinals were also having a down season and decided they wanted to look at the young guys, so they called up about eight of us.”

Reuss made his major league debut on September 27, 1969. “Red Schoendienst, the Cardinals manager was real good about getting each of the call-ups into at least one game,” Reuss remembered. “He probably felt a start against an expansion team would be best for me. The Cardinals were out of the race. It was a rainy, cool afternoon in Montreal. Tim McCarver was my catcher. If the fans were real quiet they probably could have heard my knees knocking, that’s how nervous I was. I lasted until after the second rain delay, when Red told me in the clubhouse that that would be enough and someone else would finish.”

Reuss did more than just last against the Expos. He threw seven innings of two-hit, shutout baseball with three walks and three strikeouts and earned the win in a 2-1 game. Reuss also had his first hit in that game, a seventh-inning single off Jerry Robertson that drove in Leron Lee from third base with the Cardinals’ second run. “I didn’t hit it hard. It was up the middle after a rain delay. It got by [pitcher] Robertson, [second baseman] Gary Sutherland was able to get to it and knock it down but couldn’t make a play.”

Reuss began the 1970 season with Tulsa, before earning a call-up to the Cardinals in June based on his 7-2 record with a 2.12 ERA, and 69 strikeouts in 85 innings. His WHIP was an outstanding 1.141, but it’s doubtful that entered in the Cardinals’ thinking in 1970. They knew they had a big lefty who was doing well and had kept his poise during the previous September, and he came up to the big leagues to stay for the next 18 years. He tossed a complete game on June 22 against Pittsburgh, and went six innings to get the win against Philadelphia five days later before hitting a rough patch in July with four losses and an ERA near 7.00.

“Big league competition is very fast,” Reuss said. “The difference between AAA and the Major Leagues is the biggest jump you can make, bigger than the jump from high school to pro ball, which is also a big jump. Big league hitters are a whole different animal, and you can tell just from the way they step into the batters’ box. They have experience, and their focus is incredible.”

The Cardinals stayed with him and Reuss started doing better in August. He got his first shutout against his friends from Montreal on August 9, beat the Dodgers 1-0 in a complete game on August 28, and ended the season by giving up only six earned runs in 33 innings over his last four starts. He had established himself has a member of the Cardinal rotation for 1971.

After 35 starts as a 22-year-old lefty in 1971, Reuss was traded to Houston, and it had nothing to do with his performance on the field. “When the Cardinals traded me I felt like I had been pushed out of the Garden of Eden,” Reuss said. “I was perfectly happy with the Cardinals. Originally I thought I had been traded over money. I had no interest in challenging the reserve clause, and once [Steve Carlton was traded] I was the only lefty starter still with the ballclub. I was shocked, and I thought I was traded because of how I would negotiate for my salary [Reuss said he would start high and work toward a middle figure against the team’s offer]. In 1996 I was at the ballpark in St. Louis and saw Bing Devine in the press box and asked him if he had a minute to talk. I sat down with Bing and asked him why he traded me.

“Bing told me that Fred Kuhlman [the liaison between ownership and baseball operations] had approached him and said, ‘the old man [owner August Busch] wants to get rid of Reuss. He doesn’t like the mustache.’ Bing said that when Busch would get irrational he would sit on it for awhile, but this time Kuhlman followed up a week later with the same message and he [Devine] told me he took the first offer he could get.” So on April 15, 1972, Reuss was traded to the Houston Astros for Lance Clemons and Scipio Spinks because August Busch II didn’t approve of a blond mustache.

Reuss’s 1972-1973 stint with the Astros coincided with the last stop of Hall of Fame manager Leo Durocher’s career. Durocher came from an entirely different world. He was born on a kitchen table2 in 1905 and had been managing off and on since 1939. Now he was running a team wearing orange uniforms playing indoors on plastic grass. Times had changed and there were bound to be problems in Houston. And apparently his least favorite Astro was Jerry Reuss.

According to Durocher when discussing his Astros experience in his 1975 autobiography Nice Guys Finish Last, “the only one who was real trouble was Jerry Reuss, the asshole of all time in my opinion…he was willing to admit he was the best lefthander in the league. Probably the best lefthander ever”… ‘I can throw as good as Koufax could ever throw,’ Durocher has Reuss saying. Durocher says they clashed over Reuss staying in games too long, coming out of games too soon, and matters involving his family that interfered with the team. He also says that Reuss called him a dummy.

Reuss points out today that he started 40 games and threw 279 innings in 1973, so he was clearly out there every fourth day for Durocher. Reuss does admit that he called Durocher a dummy when he was traded, but that he does not remember making the Koufax statements. “I aspired to be like Koufax, I was never in his class as a pitcher and I knew that.” As for the asshole-of-all-time remark, Reuss said that was like the pot calling the kettle black. “Leo was always fighting with someone, starting with Babe Ruth. He left the Dodgers, the Giants, and the Cubs on bad terms. It was always something with him. I was a kid. I had some problems. I was there to do my job, and I could have handled things a little bit better. [In that regard] I was right there with the rest of the world,” he said.

About 10 years later Reuss and Durocher had the chance to reconcile while Reuss was with the Dodgers. “Tommy Lasorda came up to me and asked me to come to his office. That was unusual because he usually sent someone to get you when he wanted to talk to you. I walked into the office and there was Leo sitting on the couch. He had come down from Palm Springs. Tommy said he had to step out for a minute, and that he thought Leo and I had some things to talk about. I immediately said, ‘Leo, I owe you an apology.’ Leo said, ‘That’s okay, I’ve said some things, too. You’ve changed. I apologize for being an asshole.’ ‘Me too,’ I said. Leo then told me, ‘I’m glad you’re doing well with good people.’ Then we shook hands and Tommy came back into the room. We thanked Tommy. I felt blessed to straighten things out. Then Leo and I hugged. That was the last time I saw him.”

When Reuss was traded by Houston to Pittsburgh in October of 1973, it was not nearly the shock that the mustache deal from St. Louis had been. “I’d had my adventures with Leo, and Houston needed a catcher. They had given Bob Bob Watson a try, but he was having trouble making the conversion from first base. They got a real good left hand hitting catcher in Milt May.” Reuss says he was also encouraged when Pirates General Manager Joe Brown said, “If Reuss is a problem he’ll fit right in here.”

Reuss had a string of excellent seasons with Pittsburgh from 1974 to1976, including being named by Walter Alston as the starting pitcher for the National League in the 1975 All-Star Game. He appeared in the post season for the first time while with the Pirates in two losing efforts in the NLCS. He slipped a bit in 1977 as his ERA drifted above 4.00 and he gave up more hits than innings pitched for the first time since 1971. He then had some shoulder trouble in 1978 and appeared in only 23 games, just 12 of those starts. Still, Reuss saw himself as a starting pitcher and at the end of the 1978 season asked Pirates manager Chuck Tanner if he was in the team’s plans as a starter for 1979. Reuss says Tanner assured him that he was, and Reuss tailored his off season workouts to prepare himself to start for the Pirates in 1979.

“It became obvious in spring training that I wasn’t getting the innings I would need to prepare to start, and I asked the Pirates to trade me. Chuck liked his lefty-righty matchups, and the NL East then was dominated by right-handed hitters. That put me in the bullpen, but the only time I would pitch is when the starter couldn’t get past the third inning. In 1978 Pittsburgh worked out a deal with the Cubs, but I had a no-trade clause and wouldn’t waive it because I had moved to the Pittsburgh area. I asked Harding Peterson for money to waive my no trade clause and he said no. I was then given permission to contact the Cubs, and they said they had budget problems, too, so I didn’t waive my no-trade clause then.

“In 1979 the Pirates told me they had worked out a deal with the Dodgers and gave me a few hours to talk to them. The Dodgers’ only condition was that I sign a five-year guaranteed deal immediately, which worked for me.” On April 7 the Pirates got Rick Rhoden, the right hander Tanner preferred, and Reuss became a Dodger, which turned out to be the gateway to the best years of his career.

“I was older, wiser, and therefore better,” says Reuss about his Dodger years. “In addition, I changed my workouts. I combined a free weights routine designed by Dr. Frank Jobe with Nautilus machines on the advice of Dodgers trainer Bill Buhler. I also began long distance running. From a pitching standpoint, I added a cutter which was an unusual pitch then. As a result, I could command both sides of the plate with different fastballs [his other was a sinking two-seamer] and my command improved.

“On top of that, I had confidence. I worked fast and threw strikes. The Dodgers were a great offensive club that could play good defense, and I helped make that defense better by working fast and throwing strikes. I tried to get the hitter to put the ball in play within the first three pitches. I wanted to throw two of the first three pitches for strikes. If hitters see a strike they’re gonna hack, and if the strike is to a corner they probably won’t square it up. I was happier with 18 ground balls than I was with 10 strikeouts.”

In 1980, the year Reuss was runner up for the Cy Young Award, he had a 2.51 ERA and 1.016 WHIP, and he struck out only 4.4 hitters per nine innings, compared with 8.2 in his first full year with the Cardinals. Only once in his five outstanding years in Los Angeles did Reuss strike out more than five per nine innings, and his highest WHIP in that period was 1.267. In four of those five years he averaged 2.0 or fewer walks per nine innings, meaning that he successfully applied his winning formula to great success over his best years.

As a Dodger, Reuss threw a no-hitter in May of 1980 at Candlestick Park in which the only Giants base runner came on an error by shortstop Bill Russell. He beat Houston 2-1 in the 161st game of the 1980 season to keep L.A.’s division hopes alive. His final record was 18-6

The next year, he went 10-4, with a 2.30 ERA in the strike-shortened season. He clinched the 1981 NLDS with a game five shutout, he out-dueled Ron Guidry 2-1 in game five of the 1981 World Series to give the Dodgers a 3-2 lead in a series they would win in six games, and kept his ERA under 3.00 in four separate seasons.

“Winning the World Series in ’81,” recalls Reuss, is “without a doubt” the greatest thrill in his long career. “You know why the no-hitter isn’t number one? They don’t give you a ring for a no-hitter. But they give you a ring when you win the World Series.”3

Reuss also hit his only career home run while in a Dodger uniform. “It was in 1980 off of Nino Espinosa in Philadelphia. It went down the left field line, and usually when I hit it there it drifted foul,” said Reuss, who hit left-handed. “As I rounded first base I saw the umpire give the homerun sign and thought, ‘what the hell?’ and ran around the bases. Later I was told the ball hit the top of the fence and went straight into the net at the foul pole. That was the minimum distance for a home run at Veterans Stadium.”

After a good year in 1985 (14-10, 2.92), Reuss fell off a cliff statistically in 1986 when he was 37. He went 2-6, his ERA ballooned to 5.84, and he appeared in just 19 games. A sore elbow forced him onto the disabled list and the operating table in July, and while he pitched twice in September, the surgery took a toll. “I lost velocity and I had to pitch differently,” he said. “The velocity returned slowly. I had to learn to change speeds.”

Those changes took time, and also turned Reuss into a bit of a baseball vagabond. In April of 1987 the Dodgers released him and he went to the Reds. In June the Reds released him and he went to the Angels. He was “granted free agency” that November and was signed by the White Sox at the end of spring training in 1988. His velocity had returned somewhat and he was able to put together a good season in Chicago. “By then I had mastered changing speeds. I was also running my cutter in on right handed batters in the American League who hadn’t seen me,” he said.

For the league minimum wage in 1988, Reuss went 13-9 with a 3.44 ERA and a 1.235 WHIP. His walks and strikeouts were in line with his better seasons in Los Angeles, and the White Sox tripled his salary for 1989 and made him their opening day starter. Reuss had now started on opening day for three different teams, adding the White Sox to the Pirates and the Dodgers.

Opening Day 1989 was about when the magic ended for Reuss and his left arm. He beat the Angels 9-2 in the opener, but by Memorial Day he had an ERA of nearly 7.00. On July 31 he was traded to the Brewers for Brian Drahman and finished the year going 1-4 for the Brewers with an ERA of 5.35. His WHIP was approaching 1.5, and it was becoming clear at age 40 that Reuss did not have a lot left.

Despite all that, he persevered. “I was having fun and I believed I could still pitch,” Reuss explained. “I wanted to go out on my own terms.” Going out on his own terms meant a return to the minor leagues for the 1990 season. In March he re-signed with the White Sox who released him on April 3. Eleven days later the Astros signed him and assigned him to Columbus of the AA Southern League, where he gave up only four runs in 21 and two-thirds innings. Promoted to AAA for five games, Reuss got rocked for 14 runs in five innings and was released by the Astros on May 14. Finally, the Pirates picked him up on July 7 and assigned him to Buffalo where he went a credible 4-4 with a 3.52 ERA, including and, Reuss says, a string of 25 scoreless innings at one point. Still, his WHIP was over 1.5 and he surrendered 73 hits in 61 innings. According to Reuss, Bison skipper Terry Collins and farm director Chuck LaMar told the organization that Reuss could help and should be a September call-up. As a result, he was able to pitch seven pretty decent innings for Pittsburgh, including a start on the last day of the season to wind up his career. “On that last day I was called back to the field after my outing to receive an ovation from the fans,” Reuss said. “I couldn’t imagine a better way to go out.”

At 41 Reuss decided not to pursue pitching for the 1991 season. “I was tired of calling teams and begging for another chance,” he said. Though through with pitching, he was not through with baseball. He worked three years for ESPN as an analyst on the “Hotel California” late night games with Chris Berman. Then he worked the 1995 season for The Baseball Network and the 1996 season on Angel broadcasts. From there Reuss went back to the Dodgers working on radio away games east of Colorado as part of the team that picked up the games Vin Scully didn’t work. He filled in on Las Vegas 51s Pacific Coast League games when Scully was working Dodger games.

When the Dodgers changed their radio format three years later, Reuss was released (“I’m probably the only guy released by the Dodgers as a player and an announcer.”) and coached in the minor leagues for the Expos, Cubs and Mets. That ended when he had successful knee replacement surgery in 2005. Now, Reuss lives in Las Vegas and works radio games for the 51s.

Reuss is married and has one son, one daughter and one stepson, plus five grandchildren. In his spare time he is writing his digital memoirs. He enjoys posting pictures online and writing captions for those pictures. Sportswriter Marty Noble suggested that Reuss capture and organize those thoughts into a memoir, which he is pursuing as of March 2011. “Maybe it will be a book, or maybe not. I would rather do something digital and give the reader a more full experience.” Reuss bought a high-end scanner right before his knee replacement surgery because he knew he would have a lot of downtime, and this project grew out of that purchase plus his interest in taking pictures as he pursued his baseball career. His work can be viewed at http://www.flickr.com/photos/43289453@N03/. He also has his own website at jerryreuss.com.

As Reuss approaches Social Security eligibility, it is clear he maintains a youthful outlook and a willingness to try new and different things.

Last revised: April 22, 2011

Sources

Durocher, Leo with Ed Linn. Nice Guys Finish Last. Simon and Schuster 1975

Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbooks, 1980-1987

Baseball-reference.com

Uniwatchblog.com

Interview with Jerry Reuss, March 24, 2011

Notes

1 Durocher, Leo with Ed Linn Nice Guys Finish Last p. 426

Full Name

Jerry Reuss

Born

June 19, 1949 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.