Walter Alston

Of all the many achievements that fill the Hall of Fame dossier of Walter Emmons Alston, perhaps the most impressive was the first, one that came with the final out of the seventh game of the 1955 World Series. That Brooklyn Dodger win in the final game of the season gave the city, and the team, the first world championship in the history of both. Seven times before the Dodgers had played for the title, under venerated managers like Wilbert Robinson, Charlie Dressen, and Leo Durocher, and seven times before they had lost their final game. But Alston’s patient hand provided necessary guidance and leadership for a team that had often had talent, but had never before been able to close the deal. The title was the first of four World Series rings that the Dodgers would win under “Smokey,” and was the only one claimed by the borough of Brooklyn.

Of all the many achievements that fill the Hall of Fame dossier of Walter Emmons Alston, perhaps the most impressive was the first, one that came with the final out of the seventh game of the 1955 World Series. That Brooklyn Dodger win in the final game of the season gave the city, and the team, the first world championship in the history of both. Seven times before the Dodgers had played for the title, under venerated managers like Wilbert Robinson, Charlie Dressen, and Leo Durocher, and seven times before they had lost their final game. But Alston’s patient hand provided necessary guidance and leadership for a team that had often had talent, but had never before been able to close the deal. The title was the first of four World Series rings that the Dodgers would win under “Smokey,” and was the only one claimed by the borough of Brooklyn.

Walter Emmons Alston was born on December 1, 1911, in Venice, Ohio, a few miles northwest of Cincinnati. His father, Emmons Alston, was a farmer, and Walt’s mother Lenora (Neanover) was a homemaker. Walt’s formative years were spent on a farm near Morning Sun, Ohio, but there were few neighbors nearby with which to play. Alston shared some thoughts on his childhood with John Flynn Dreyspool of Sports Illustrated magazine in 1955: “When the old man wasn’t there to play catch with me, I was bouncing the ball around on the barn door. That’s how I got my nickname, ‘Smokey,’ ‘cause I used to have a real fast fireball.”

The Alstons moved to Darrtown when Walt entered his teenage years, and that gave him the chance to play baseball more regularly on a local sandlot. At Darrtown High School “Smokey” captained the basketball and baseball teams and helped the 1928 baseball squad the Butler County championship. He graduated from high school in 1929, two years after electric power arrived in Darrtown, and enrolled at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. Alston drove a laundry truck to finance part of his education, and also worked in the school cafeteria and moonlighted at a local pool hall.

In 1930 he married local girl Lela Alexander. The responsibilities of marriage forced Walt to withdraw from college for two years in order to establish a more reliable financial plan for his education. He re-enrolled in 1932, at the nadir of the Great Depression, yet was able to not only letter in both baseball and basketball all three years, but also to complete work for his degree in education. He found time to play Sunday baseball in the Clark-Butler County League, where he pitched and played both corner infield positions.

After he left college in 1935, Alston accepted a position as a high school science, biology, and industrial arts teacher, and basketball coach, in the New Madison school district. It was around this time that the St. Louis Cardinals, who were familiar with his success on the college diamond, offered Alston a contract and a chance to play third base for the Greenwood Chiefs of the class C East Dixie League. In 319 at-bats Alston hit .326 and, after an offseason of teaching and coaching, earned a move to the Huntington Red Birds of the Mid-Atlantic League. At the end of the 1936 minor league season, a year in which his batting average of .326 and his 35 home runs garnered the attention of team executives in St. Louis, Alston was called up as insurance for what proved to be an unsuccessful September pennant run.

On September 27, 1936, Cardinal star rookie Johnny Mize was ejected in the final game of the season, a Sunday tilt against the Cubs, and manager Frankie Frisch sent Alston in to make his major league debut. It was hardly the stuff of legend. In three innings at first base behind pitcher Dizzy Dean, Alston had two chances in the field and made an error on one of them. At the plate in what turned out to be his sole major league at-bat and facing Cub ace Lon Warneke, Walt whiffed on three pitches. The next spring the Cardinals, having Mize ensconced at first base, assigned Alston to the Houston Buffaloes of the Texas League. The slugger never played in the majors again.

Smokey had given up teaching, but with daughter Dorothy to look after, he and Lela spent the next decade in the minor leagues, in cities like Rochester (New York), Portsmouth (Ohio), Columbus (Georgia), and Springfield (Ohio), chasing another shot at the majors. They would return to Ohio after every offseason until his retirement in 1976, but each spring he would try again to prove his worth. His offensive production never again equaled that 1936 season, however. Eventually the Cardinals, having observed him closely, suggested Walt try managing. In 1940 he replaced Fred “Dutch” Dorman at the helm and served out the season as player-manager for Portsmouth in the Mid-Atlantic League. On the field he knocked 28 home runs, but on the bench managed just well enough to keep the Red Birds out of the cellar.

Alston played and managed the next two seasons at Class C Springfield, in 1941 hammering 25 more homers and guiding the team to a 69-51 record and the playoffs before losing in the first round. In 1943 Walt relinquished the reins and returned to full-time playing for Rochester in the International League, but his batting average dipped to .240. It was the last season that he would not manage a team. Walt started the 1944 Rochester season with only three hits in the team’s first thirteen games. The Cardinals, reasonably assuming that the shelf life on the 32-year-old minor league slugger was nearing expiration, released him.

The Brooklyn Dodgers jumped at the opportunity afforded by the Cardinals’ decision and signed Alston as player-manager of the Trenton Packers in the Class B Interstate League on July 28. Alston replaced Joe Bird as skipper and led the team, with a record of 32-57 when he arrived, to a 31-18 mark over the final 49 games. Two years later Alston managed the Nashua Dodgers to the 1946 New England League title, and repeated the feat with the Pueblo Dodgers in the Western League the following season. Walt was promoted to manage the Dodgers’ AAA American Association team in St. Paul, and then moved to Montreal in 1950.

In his six years managing at the AAA level, between 1948 and 1953, Alston’s teams won three league titles, one Junior World Series championship (1949), and posted a composite 544-373 record. When Brooklyn owner Walter O’Malley decided he would not meet Dodger manager Charlie Dressen’s request for a multi-year contract, the owner chose his AAA skipper to manage the big-league club. O’Malley gave Alston a one-year contract, the first of 23 that the manager would eventually sign.

“Who’s he?” New York Times sportswriters queried as spring training began in 1954. Alston was taking over a team that had been riding a wave of success. Since Bobby Thomson’s home run in the 1951 playoff with the Giants, the Dodgers had won consecutive National League pennants in 1952 and 1953, losing to the Yankees both years in the World Series. It was a roster filled with talented players like Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, and Duke Snider, so expectations were high. In Alston’s first year in the dugout, 1954, the team won 92 games. But lost the pennant to the cross-town rival Giants, a team that rode the shoulders of Willie Mays in defeating the heavily favored Indians in the World Series, but the new manager endured public criticism for failing to meet expectations.

The team was only one game out of first place on June 27, but within three weeks had slumped to seven games back. The Dodgers rallied back to within a game of the lead, but another slump in September scuttled their chances. There was scuttlebutt that Jackie Robinson did not respect Alston. In Rudy Marzano’s book The Last Years of the Brooklyn Dodgers: A History, 1950-1957, he quoted Robinson in the aftermath of an early September loss in Chicago, a game in which Duke Snider had been awarded a double on a fly ball that should have been ruled a home run, yet Alston did not contest the call. “The team might be moving somewhere if Alston had not been standing at third base like a wooden Indian,” Robinson said. Between the slumps and comments such as those from Robinson and Billy Loes, the daily sports pages became a daily workshop for dissecting the manager.

Following the next season, after 98 wins and a World Series victory over Mickey Mantle and the Yankees, Alston went all the way from “bush leaguer” to Sport magazine’s “Man of the Year” for 1955. It was a turnaround possible only in a media capital like New York City.

Alston’s Dodgers followed in 1956 with another National League pennant but lost to the Yankees in a World Series rematch. It took the American Leaguers seven games, including a perfect game by Don Larsen, to wrest the title from Brooklyn, and it proved to be the Dodgers’ final title shot before moving to Los Angeles.

Walter O’Malley’s move, along with Horace Stoneham’s Giants, to the West Coast created a tectonic shift in the baseball landscape. Both teams arrived in their new cities to play in interim ballparks. The Dodgers made camp in the Los Angeles Coliseum, a single-tiered, oval edifice constructed in the 1920s that was well suited to track and field, most visibly during the 1932 Olympic Games, and football, as home to the University of Southern California, but required some creative adaptation as a baseball facility. For a team constructed to exploit the dimensions and nuances of Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, the new home offered a schizophrenic challenge to pitchers, hitters and managers. There was virtually no foul territory on the first- base side, yet the area behind the plate and on the third-base side was vast. Conversely, the left-field foul pole was a mere 251 feet from home plate, and Commissioner Frick demanded that the Dodgers put up a 42-foot-high fence in left field to minimize, as much as possible, cheap home runs. The Dodgers fell to seventh place in their new home.

Alston, with a pitching staff that included youngsters Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale, as well as veterans Johnny Podres and Roger Craig, led his 1959 team to the National League pennant, their first in Los Angeles, and a World Series win over the “Go Go” White Sox. The seeds of the team’s future were also faintly visible on the 1959 champions. Along with Brooklyn transplants like Snider, Hodges, Podres, and Craig, there were a number of new Los Angeles Dodger faces on the roster. Names like Ron Fairly, Maury Wills, Tommy Davis, Frank Howard, and Stan Williams began to show up in box scores. Those players formed the core of the team that would open Dodger Stadium in Chavez Ravine in 1962.

The 1961 Dodgers finished only four games off the pace, behind the Cincinnati Reds, a favorable portent for 1962. It was that year, however, that provided another test of Alston as a major league manager. The team was ahead of the Giants by four games with only seven to play yet fell into a tie with their long-time rivals at the end of the regular season. San Francisco won the three-game playoff two-games-to-one and went on to the World Series against the Yankees while the Dodgers went home. There were heated calls in the Southern California press for Alston’s ouster, and some rumored dissent in the locker room, but Smokey never panicked, never wavered. He had told Sports Illustrated in 1955, “I think I learned my lesson in St. Paul. One year we had a six-game lead and nine games to play and we end up winning the pennant by one-half game and we had to win a double-header the last day of the season to do it.” For Alston, it was paramount to play the next game and not worry about the game next week, or next season. In 1963 the Dodgers won 99 times en route to another National League pennant, and then swept the defending champion Yankees 4-0 in the World Series.

In 1965, the Dodgers defeated the Minnesota Twins in the Fall Classic, but Alston again fell under the media microscope the following year when the Dodgers fell to the Baltimore Orioles in a four-game World Series sweep. The team spent the next decade re-inventing itself a third time.

The “Boys of Summer” had won in 1955 with a veteran roster laden with power hitters and adequate pitching. By the end of the 1965 championship, the team was clearly built around pitching prowess and the physical advantage provided in the wide open spaces of Dodger Stadium. In 1974, the year of Alston’s final National League championship, the team had shifted to a balance of pitching (Don Sutton, Tommy John, and Mike Marshall) and all-around offense (Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, and Jimmy Wynn, among many). In each iteration, the colors of the uniforms remained constant but the names on the backs changed and the managerial approach necessary for success altered dramatically.

Walt Alston, clearly, handled those changes well. On July 17, 1976, he became the fifth manager ever to reach 2,000 career wins (in 2011 he remains ninth all-time). Two months later—after his final game as Dodger manager, a 1-0 loss to J.R. Richard and the Houston Astros on September 28, 1976–his season’s record stood at 90-68. Following that game the 64-year old Alston handed the team over to third-base coach Tommy Lasorda, a long time ally since their days in Montreal, and walked away.

He and Lela returned to Darrtown, their home until Walt passed away on October 1, 1984, in Oxford, Ohio. He is buried in Darrtown Cemetery. In 2000 the proud town erected a statue of Alston, in the center of the town.

Walter Alston’s legacy is dazzling, even decades after his retirement, and choosing his second-most impressive achievement, after the 1955 championship, is nearly impossible. His Dodger teams, over 23 years, suffered but four losing seasons despite franchise relocation and three different home parks. His teams won 90 or more games in 10 different years, and he was three times named Major League Manager-of-the-Year, and six times National League Manager-of-the-Year. He managed eight National League All-Star teams, winning seven of those games, and even found time to co-author a book, the Complete Baseball Handbook: Strategies and Techniques for Winning, with Don Weiskopf, along with his autobiography, A Year at a Time, with Jack Tobin. His Dodgers won 2,040 games under his leadership, and in 1983 the Veteran’s Committee elected him to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Widely acclaimed sportswriter Jim Murray wrote a column–it appeared in the Hamilton (Ohio) Journal-News, among many outlets—about Alston following the manager’s retirement. “I don’t know whether you’re Republican or Democrat or Catholic or Protestant and I’ve known you for 18 years.” He continued, “You were as Middle-Western as a pitchfork. Black players who have a sure instinct for the closet bigot recognized immediately you didn’t know what prejudice was…There was no ‘side’ to Walter Alston. What you saw was what you got.”

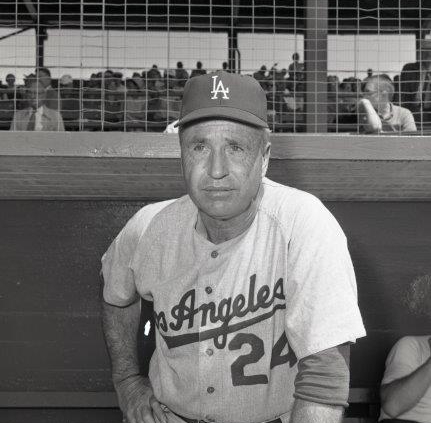

Photo credit

Walter Alston, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Sources

Alston, Walter, and Jack Tobin. A Year At A Time. Waco: Word Books, 1976.

Alston, Walter, and Don Weiskopf. Complete Baseball Handbook: Strategies and Techniques for Winning. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1972.

Dreyspool, John Flynn. “Subject: Walter Alston.” Sports Illustrated, July 11, 1955.

Fiztgerald, Ed. “Man of the Year.” Sport, March 1956.

Hamilton Journal-News (Ohio). October 8, 1976.

Marzano, Rudy. The Last Years of the Brooklyn Dodgers: A History, 1950-1957. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2007

New York Times. October 1, 1956.

Full Name

Walter Emmons Alston

Born

December 1, 1911 at Venice, OH (USA)

Died

October 1, 1984 at Oxford, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.