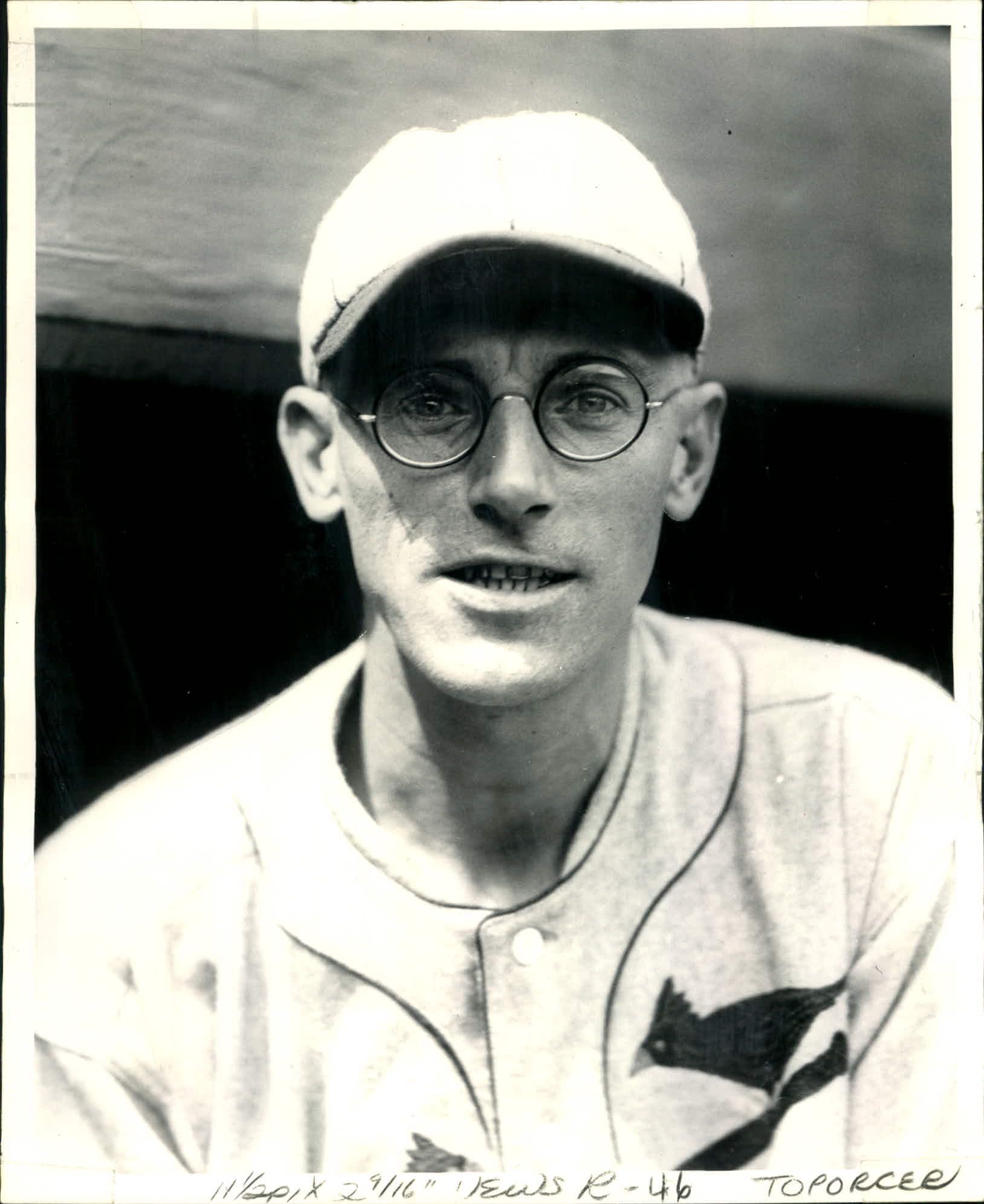

Specs Toporcer

Here is one of the most moving, human-interest stories in the entire history of the game—a story that exemplifies the spirit of baseball and America . . . It is the . . . dramatic story of the skinny, under-nourished, weak-visioned kid, the son of a poor immigrant family, a product of New York’s tough East Side, who, against overwhelming odds, rose to success in the game.1

Here is one of the most moving, human-interest stories in the entire history of the game—a story that exemplifies the spirit of baseball and America . . . It is the . . . dramatic story of the skinny, under-nourished, weak-visioned kid, the son of a poor immigrant family, a product of New York’s tough East Side, who, against overwhelming odds, rose to success in the game.1

This advertisement was employed to sell copies of The Sporting News that, over a three-part series in February-March 1952, told the riveting story of George “Specs” Toporcer’s life. The series described his four-decade career in professional baseball, a career cut short after detached retinas caused him to go blind in 1951. Joking that he could now serve as a major league umpire, Toporcer described himself as “a very lucky guy”—a remarkable claim considering the death of his 16-year-old son just six years earlier.2 Undaunted by these setbacks, Toporcer launched a second career as a motivational speaker that earned him the nickname of “Baseball’s Blind Ambassador.”3

George Toporcer (pronounced Ta-PORE-Sir) was born on February 9, 1899, the sixth of seven children of Andreas “Andrew” and Anna Marie Toporczer in New York City, New York.4 In 1890, Andrew, Anna and their then-three children, all natives of Austria-Hungary, immigrated to the United States and settled in Yorkville, a neighborhood in the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Andrew, a modest cobbler who listed himself as an inventor in the 1910 US census, raised his family in a small second floor apartment above his shoemaking shop. The children attended P.S. 158, where George’s classmates included future Hollywood star James Cagney. All the Toporcer children appear to have been quite athletic, especially George’s youngest sister Betty, who excelled at basketball and high jumping, and his baseball-playing older brothers Gus and Rudie. Though George tried to follow in his brothers’ footsteps, his thick glasses—which earned him the nickname “Specs”—and his rail-thin build generally caused him to be bypassed during his school’s baseball activities. The snub appears to have served as a catalyst for the youngster to learn more about the game.

In 1912 the 13-year-old Specs took a job “posting major league scores on a huge blackboard in the backroom of a corner saloon . . . [for] 50 cents a week and all the liverwurst and crackers [he] could eat.”5 The job turned especially exciting for him that autumn when the New York Giants, the club that he and his brothers idolized, made it to the World Series. But it ended abruptly the next year when family patriarch Andrew Toporczer died. With no more than an eighth-grade education, Specs quit school to help his siblings run the family shop. Despite this added responsibility, they continued making time for athletic pursuits, a lenient policy that allowed Specs to hone his baseball skills on the sandlots in his spare time.

In a few short years Toporcer advanced from pickup play to semi-pro ball where he quickly captured the attention of fellow East Side ballplayers Charlie Niebergall and Joe Benes. The meeting proved fruitful to Specs after the pair, advanced to the International League’s Syracuse Stars in 1920, recommended Toporcer to club owner and former minor league player and manager Ernest (Duke) Landgraf. Meeting Landgraf in June in the same stadium in which he would make his managerial debut 11 years later, Toporcer made such a positive impression that the owner was prepared.to hire him on the spot. But the youngster was unable to sign due to contractual obligations with a Brooklyn-based semi-pro club and the fact that his mother was gravely ill. When Anna died a month later, Toporcer bolted the Brooklyn club and, under an assumed name, played for a team in Orange, NJ. Besides opponents in its eight-club circuit, the Orange team scheduled several games outside the league, including an October contest against a barnstorming club consisting of several present and former Philadelphia Athletics players, and a match against the Negro National League’s Bacharach Giants. The latter contest was attended by Landgraf, who again pressed Toporcer to sign. Having been briefly courted by the major league Brooklyn Robins, Toporcer hesitated for two months before eventually signing with Syracuse.

Though Toporcer is only known to have played second and possibly third base throughout his sandlot career, he possessed the versatility to adapt to nearly any position, an asset that soon served him well. During the 1920-21 offseason Landgraf struck an agreement with the St. Louis Cardinals that allowed Syracuse to operate as the major league club’s Class-AA affiliate. When veteran third baseman Milt Stock refused to report to the Cardinals’ 1921 spring training, claiming he would go into business with his father-in-law in Mobile instead, Cardinals manager Branch Rickey moved Rogers Hornsby to the hot corner and selected 5’10”, 135-pound Toporcer from the Syracuse roster to replace the future Hall of Famer at second. The move paid off when Toporcer, on the strength of a strong spring that included a 4-for-4 game with one homer during a win against the New York Yankees in Lake Charles, Louisiana, earned a spot on the Cardinals roster.

Shortly before the start of the regular season, Rickey was forced to rejuggle his lineup after Stock rejoined the Cardinals. On April 13, 1921, Toporcer made his major league debut, and is believed to have made history as the first bespectacled non-pitcher in the major leagues, at Chicago’s Cubs Park as the Cardinals’ second baseman, with Stock at third and Hornsby in the outfield. Absent from the lineup was veteran outfielder Les Mann, who had been acquired from the Boston Braves during the off-season but was limited to pinch-hit duties over the first six games of the season. During the Cardinals’ 5-2 loss, Toporcer batted twice against Cubs ace righthander Pete Alexander with no success before capturing his first major league hit in the eighth inning against reliever Buck Freeman. Toporcer remained in the starting lineup over the next five games until Mann was ready to resume his place in the outfield, at which point Hornsby was reinstated at his familiar second base.

Over the next six weeks Toporcer got only one start and made just eight plate appearances before the Cardinals sent him to Syracuse to get playing time. Twice he returned to the Cardinals, first after the Cardinals traded utility infielder Hal Janvrin to the Robins, and again when rosters expanded in September, but he received just five starts over the two call-ups.

As events unfolded, 1921 also proved to be significant to Toporcer for reasons other than his major league debut. In one of the Cardinals’ three trips to the Polo Grounds during the 1921 season, Toporcer met fellow New York City native Madeline Mabel Pilegard. Five years his junior, Madeline, an accomplished athlete in her own right, especially in badminton, had grown up less than 10 miles from Toporcer. Moreover, she had also grown up as an avid Giants fan, a passion which placed her in the Polo Grounds the day Toporcer spied her. The chance meeting blossomed into romance and they married on New Years Eve 1922. The union produced a daughter twelve months later and a son in 1929.

With no chance of replacing Hornsby at second base, Toporcer’s second consecutive strong spring proved sufficient to unseat veteran Doc Lavan and claim the bulk of play at shortstop for the Cardinals during the 1922 season. On May 15 he collected several major league firsts with a homer, two triples and a career-high five RBIs in helping lead his club to a 19-7 rout of the Philadelphia Phillies. In the next game Toporcer got his second career home run during an equally lopsided 11-0 win against the Robins. He finished the season with career-high marks in nearly every offensive category while placing third in OBP among Cardinal starters, trailing only Hornsby and outfielder Jack Smith.

But as much as he had hoped to shake it, Toporcer eventually developed a reputation as a “jack-of-all-trades [utility infielder] who [was] always valuable in an emergency.”6 Over the next six years he filled in at every infield position, plus one game in the outfield, while averaging just 194 at-bats per season. Despite such limited play— which he never complained about—Toporcer often delivered for the Cardinals, sometimes in crucial situations. Possessing an uncanny ability to put the bat on the ball throughout his career, Toporcer was the only player who did not whiff on July 20, 1925, when Dazzy Vance established a modern record 17 strikeouts in a game against the Cardinals. But nothing proved more vital than the pinch-hit RBI double he launched on September 24, 1926, driving in two runs to help the Cardinals clinch their first NL pennant in franchise history. During these six years, several teams approached the Cardinals about a trade for the utility player—none more so than the Robins and the Boston Braves—but Branch Rickey, a strong advocate of Toporcer, would not hear of it. As was later revealed, Rickey had already begun grooming Toporcer for a future managerial berth with the Cardinals.

After Rickey was replaced by Hornsby as the team’s field manager in 1925 (The Mahatma stayed on as the club’s GM), the Cardinals went through two additional managerial changes in quick succession. One such change came ahead of the 1928 season when the team hired veteran skipper Bill McKechnie. Unlike his predecessors, McKechnie appears to have had little regard for Toporcer, using the utility player just eight times during the first seven weeks of the season. The eighth appearance came in Philadelphia on June 2 when Toporcer replaced injured second baseman Frankie Frisch in the second inning of a game against the Phillies. He struck out in two of three at-bats in what proved to be his last major league appearance. Shortly thereafter Toporcer was sent to the Class-AA Rochester Red Wings in the International League in what appears to be a move by the Cardinals to clear roster space for free agent pitcher Clarence Mitchell. Toporcer departed the majors with a .279/.347/.373 batting line in 1,566 at-bats.

The Rochester assignment reunited Toporcer with a former Cardinals teammate, player-manager Billy Southworth, in a continuation of what became a decades-long interaction between the two. In 1929 Toporcer, the club’s second baseman, team captain and league MVP, helped Southworth guide the Red Wings to a circuit championship (the second of four straight) while also establishing a professional-record 223 double plays—amid rumors that “late in the season (after the pennant was clinched) Rochester pitchers intentionally walked batters with less than two outs to set up double play possibilities.”7 Though a second MVP award for Toporcer and a third title for the club ensued during the next year, the team captain had nearly been forced to sit out the season because of what was dubbed “The Toporcer incident.”8

On October 13, 1929, during the last game against the Kansas City Blues in the Little World Series, home plate umpire Larry Goetz called Toporcer out on strikes with two on and two out in the ninth inning. As Cardinals hurler Fred Toney could testify, six years earlier when he had tried to reposition Toporcer during a game, the infielder, despite his small stature, was no shrinking violet when it came to disputes. Reportedly bumping and shoving the umpire after the third strike call, Toporcer was ejected from the game. Initially refusing to leave, he returned to the field after the Red Wings lost and allegedly tried to incite the Rochester fans to attack the umpire crew. Shortly after the Series ended, the International League fined Toporcer for his actions and the matter appeared closed. But in November, National Association president Michael H. Sexton issued a one-year suspension against Toporcer as well as a $500 fine against Southworth for his failure to restrain his player. The harsh penalty against Toporcer produced a massive backlash from International League fans, owners and players (opposing and teammates), many of whom cited run-ins that Goetz had had with players in the past. In December Branch Rickey, who appealed Sexton’s ruling on Toporcer’s behalf, got the suspension lifted in favor of an additional $500 fine.

Rochester returned to the Little World Series in 1930 and 1931 where they defeated the Louisville Colonels and St. Paul Saints, respectively. In 1930, Toporcer helped the team by leading the circuit in doubles (49) and walks (125). After a brief managerial stint with the Jersey City Skeeters in early 1931, he was traded back to the Red Wings in July for infielder Jimmy Jordan, outfielder Bill Hinchman and cash. Toporcer took over the Red Wings’ helm during the 1932 season after Southworth’s departure to accept a managerial post with the Cardinals’ Columbus, Ohio, affiliate.

Toporcer remained with the Red Wings as player-manager over the next three seasons. Though no further titles ensued, he earned second runner-up in the balloting for the circuit’s 1932 MVP award. But over the next two seasons injuries and diminished play began to overtake the mid-30s veteran. In January 1935, when team president Warren Giles extended a 1935 contract with a considerable pay cut, Toporcer balked. Though he’d successfully held out for higher pay in the past—with St. Louis in 1925 and Rochester in 1932—this time the organization did not budge. The Red Wings released Toporcer a week later.

Snatched up by Syracuse Chiefs manager Nemo Leibold, who appears to have developed a relationship with him when both were managing in the Cardinals organization in 1932, Toporcer served as team captain while playing second base for the Boston Red Sox Class-AA affiliate throughout the 1935 season. When the season ended, rumors surfaced that Toporcer would replace Bob Shawkey as manager of the Yankees’ Triple-A affiliate in Newark, NJ. Determined to not lose him, the Red Sox appointed Toporcer as president and player-manager of their Class-B affiliate in Rocky Mount NC. Though a severe knee injury in June 1936 essentially ended his playing career—he made just 33 appearances over four seasons through 1941—Toporcer’s strength in “developing young talent” helped in constructing his long career as a manager and later as a farm director.9

“[Toporcer] knew more baseball than you could ever think about,” Rocky Mount hurler Charlie Wagner recalled years later. “[Moreover, we learned from him how to live the right way . . . It was a joy to play for him.”10

When Ralph Kiner was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1975, Toporcer took pride in having been his first professional skipper.

In October 1938, Toporcer and Southworth competed with several other candidates for the managerial post with the Montreal Royals before the Class-AA club selected former pitching great Burleigh Grimes. Two months later Toporcer signed a three-year contract to manage the Red Sox Class-A-1 affiliate in Little Rock AR. He lasted just one year. As indicated in April 1937 when he nearly came to blows with Trenton Senators player-manager Bud Shaney over whether a ball should remain in play, age had done little to arrest Toporcer’s irascible nature. Clashing with the Little Rock owners throughout the 1939 season—there is no indication these clashes resulted in fisticuffs—both parties appeared satisfied when the multi-year contact was terminated after just one season.

In November, another Cardinals associate, former teammate and newly hired Pittsburgh Pirates manager Frankie Frisch, convinced the team’s owner to tap Toporcer as manager of the club’s Class-A Albany Senators. “Don’t let his glasses fool you,” Frisch told an Albany audience shortly after the hiring. “[Toporcer] is not only an able leader, but a grand fellow.”11 In 1940 a late-season surge by the Senators allowed Toporcer to steer the club into the Eastern League playoffs. But no such fortune prevailed the next season as the club tumbled to a sixth-place finish, a dismal result that ended in Toporcer’s release.

Shortly afterward Toporcer returned to the Red Sox as a scout. In 1942, after the United States entered the Second World War, he found work in Rochester with a company that made aircraft surveillance cameras while continuing his scouting in the Northeast. A year later he spurned an offer to manage in Montreal to accept an appointment with the Red Sox as the club’s farm director after the incumbent, former pitching great Herb Pennock, departed to take the GM job with the Phillies. Toporcer approached his new responsibilities with the same emphasis on detail that he’d applied to his former posts. “I’d rather have a fistful of emeralds than a bucket of rhinestones,” he explained. “We select the best leaders money can hire . . . Then I, as head of [owner Tom] Yawkey’s farm system, travel around and have sessions with the managers—making sure they teach exactly the same methods of operations that [Red Sox manager Joe] Cronin himself teaches . . . A boy coming up to the Red Sox can be sure he’ll receive a lot of personal attention.”12 One of Toporcer’s hires was Charlie Niebergall, his East Side teammate whose 1920 recommendation had helped launch Toporcer’s long professional career. Toporcer’s tenure as the Red Sox farm director lasted five years until he got caught up in the club’s housecleaning following Boston’s playoff loss to the Cleveland Indians on October 4, 1948.13

A month later Toporcer, never one to be unemployed for long, was appointed as the farm field director for the Chicago White Sox. He remained in this capacity for two seasons before the lure of an on-field job deposited Toporcer in upstate New York to manage the Triple-A Buffalo Bisons. Though he earned the circuit’s 1951 Manager of the Year award for lifting the last-place club to a 79-75 record, Toporcer was not with the team when the honor was announced.

In January 1948, Toporcer had surgery to restore sight to his left eye following a retinal detachment. When the operation proved unsuccessful he was blind in one eye. Around July 1951 the same symptoms began affecting his right eye, forcing Toporcer to leave the Bisons. He underwent three operations between October and November in a failed attempt to save his sight. Toporcer returned to Rochester, his home since the winter of 1928-29, where his wife Madeline became his fulltime aide.

Throughout his playing career Toporcer maintained a frenetic lifestyle during the off-seasons. In 1933-34, he became a radio celebrity in Rochester working alongside WHEC radio station manager and Red Wings’ broadcaster Gunner O. Wilg on a program called “Hot Stove Baseball.” Toporcer would return to the broadcast booth several off-seasons thereafter. He worked as a salesman for the Standard Oil Company in Rochester before eventually starting an amateur baseball school. Despite this busy schedule Toporcer, an avid hiker, was known to walk 30 miles a day. In 1934 he added piano lessons to the little leisure time he had (it is unclear how long he continued this musical pursuit). Also uncertain was whether he maintained a strict vegetarian diet that was heavy on cold cereals during the off-seasons and after his playing career. In February 1939, for the first of at least two years, Toporcer made up part of an All-Star lineup that included Southworth, Branch Rickey, Rabbit Maranville and others who participated in a baseball clinic at the University of Rochester. Toporcer’s frenzied behavior seemingly increased in 1945 as he appears to have tried to drown his sorrow with work following the March 18 death of his 16-year-old son Robert, a three-sport athlete at Rochester’s Brighton High School before an undisclosed illness left him bedridden for six months prior to his passing. Toporcer was also a favorite on the rubber chicken circuit. Except for the last, almost all these pursuits went astray after Toporcer went blind.

In 1952 the Bisons and Cardinals raised approximately $28,000 in charity exhibitions against the Cincinnati Reds and Red Sox, respectively, to help Toporcer defray the costs of his numerous eye operations. Around the same time Toporcer began dictating to his wife a part-autobiography, part- baseball instruction book entitled Baseball—From Backlots to Big Leagues, a text that was well received when it was released in 1954. Even before the book’s release Toporcer’s story was picked up by America’s rapidly-growing sensation, television. On October 9, 1953, ABC-TV’s series “Comeback Story” broadcast “Toporcer’s courageous battle against blindness.”14 Hosted by entertainer George Jessel, the program included in-person tributes from various dignitaries including then-NL president Warren Giles and recent Hall of Fame inductee Frankie Frisch, as well as submitted testimonials from Branch Rickey and James Cagney.

Citing overly rough hands from his long baseball career, Toporcer was never able to learn braille. He was forced to rely heavily on his wife for the simplest things throughout the remainder of his life. Around 1954 he launched a second career as baseball’s goodwill ambassador. Chauffeured by Madeline, Toporcer toured large portions of the United States to speak about the sport he so loved. Between fall 1956 and spring 1957 he logged thousands of miles and spoke to an estimated 100,000 students during a tour of 200 schools throughout the Midwest. During this time, Toporcer was a fan favorite at various Old Timers Games around the country while also drawing various honors, including his induction into the International League Hall of Fame and the Rochester Sports Hall of Fame, and being selected by Rochester sportswriters as the Red Wings all-time greatest second baseman. On August 22, 1976, Toporcer was one of eight surviving members present at Busch Stadium (two were unable to attend) when the Cardinals celebrated the 50th anniversary of the club’s first world championship.

Around January 1956 Toporcer moved from Rochester to Huntington Station, Long Island, where he remained over the next three decades. On May 17, 1989, three months after his 90th birthday, he died from injuries suffered in a fall at his home. He was buried at Melville Cemetery in Melville, Long Island. He was survived by his wife, his youngest brother William, and five grandchildren, his daughter having preceded him in death three months earlier.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank SABR member Norman Macht for review and edit. This biography was fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 “Specs Toporcer, Now Blind, Looks Back Over Career,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1952: 37.

2 “Maglie, Toporcer Receive Awards at Buffalo March of Dimes Meeting,” ibid., January 23, 1952: 18.

3 Fred G. Lieb, “Sightless Toporcer Game’s Speaking Ambassador,” ibid., May 14, 1958: 28.

4 George and his siblings dropped the “z” from their surname during the 1920s.

5 George (Specs) Toporcer, “Toporcer, Blind, Tells of Struggles,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1952: 3.

6 “Five Cards Who Look Like Triumph to Rogers Hornsby,” ibid., March 25, 1926: 3.

7 “’29 Wings Set O.B. Record: 223 DPs, Two Triple Plays,” ibid., December 1, 1962: 6.

8 “Branch Rickey’s Eloquent Plea Lifts Toporcer Suspension,” ibid., December 12, 1929: 3.

9 “Travelers All Set for Fast Get-Away,” ibid., February 23, 1939: 6.

10 Interview with Norman L Macht, December 9, 1991.

11 “Rose-Colored Glasses Given ‘Specs’ Toporcer,” The Sporting News, January 25, 1940: 8.

12 Roger Birtwell, “Toporcer Rates B.R. Genius, But—” ibid., March 19, 1947: 4.

13 Though one source reported that Toporcer, citing ill health, resigned, all other reports indicate that he was swept up in the complete makeover of the Red Sox farm system.

14 “Dramatize Spec Toporcer Story,” The Sporting News, October 21, 1953: 25.

Full Name

George Toporcer

Born

February 9, 1899 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

May 17, 1989 at Huntington Station, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.