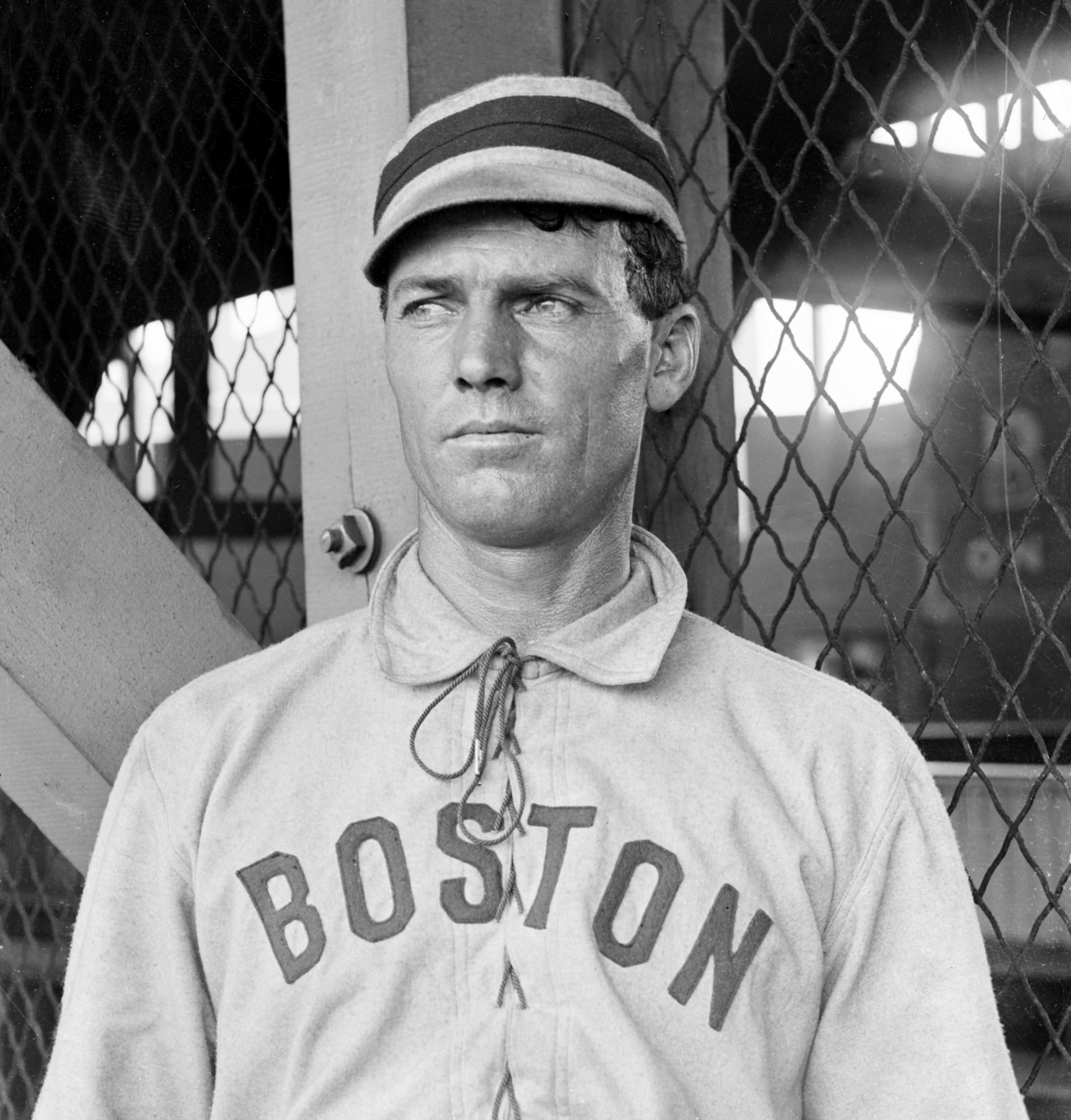

Buck Freeman

The first legitimate home run hitter in baseball history, Buck Freeman escaped the coal mines of Northeastern Pennsylvania to become one of the premier sluggers during the first decade of the American League. Freeman won seven home run titles during his professional career, and his astonishing 25 homers for the Washington Senators in 1899 shocked the baseball world. After jumping to the Boston Americans, Freeman played a key role in that club’s capture of the 1903 World Series and 1904 pennant. Umpire Tim Murnane called Freeman “the batting wonder of the age.”1 The Washington Post agreed: “Modern base ball has never produced his like,” a Post reporter wrote. “Even the eagle-eyed Anson, the slugging Brouthers of the falcon-eye, the mighty Tip O’Neill… all move back a niche in the game’s history, and make room for one who is their master.”2 Freeman broke the single-season home run records in the New England League, Eastern League, and American Association, while nearly doing the same in both the American and National leagues. During his peak from 1899 through 1905, Freeman led all major-league players with 77 home runs, outdistancing his nearest competitor, Nap Lajoie, by 28.

The first legitimate home run hitter in baseball history, Buck Freeman escaped the coal mines of Northeastern Pennsylvania to become one of the premier sluggers during the first decade of the American League. Freeman won seven home run titles during his professional career, and his astonishing 25 homers for the Washington Senators in 1899 shocked the baseball world. After jumping to the Boston Americans, Freeman played a key role in that club’s capture of the 1903 World Series and 1904 pennant. Umpire Tim Murnane called Freeman “the batting wonder of the age.”1 The Washington Post agreed: “Modern base ball has never produced his like,” a Post reporter wrote. “Even the eagle-eyed Anson, the slugging Brouthers of the falcon-eye, the mighty Tip O’Neill… all move back a niche in the game’s history, and make room for one who is their master.”2 Freeman broke the single-season home run records in the New England League, Eastern League, and American Association, while nearly doing the same in both the American and National leagues. During his peak from 1899 through 1905, Freeman led all major-league players with 77 home runs, outdistancing his nearest competitor, Nap Lajoie, by 28.

John Frank Freeman was born on October 30, 1871, in Catasauqua, Pennsylvania, near Allentown, to Irish immigrants John and Annie Freeman. The elder John Freeman, born in Ireland at the height of the potato famine, emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1865. When young John was 8 years old, the family moved to coal mining country near Wilkes-Barre, where first the father and later the son found work at what was reputed to be the largest coal breaker in the world. Young John lied about his age to get the job, and worked his way up from slate picker to – at age 12 – the more glamorous job of mule driver. Much to the dismay of his parents, John found he liked baseball more than the mines, and starred as a pitcher on various local semipro teams. In 1891 the Washington Statesmen of the major-league American Association gave Freeman a trial, but the 19-year-old southpaw quickly earned his release by walking 33 batters in five games.

Back in Wilkes-Barre, Freeman began pondering the sage advice given him a few years earlier by Bud Fowler, the first African-American player in professional baseball, who had reportedly witnessed the 16-year-old Freeman hit two home runs in an 1888 sandlot game. “I never gave batting a thought until Fowler tipped me off,” Freeman said. “You have pretty good control of the ball for a left-handed pitcher, kid,” Freeman claimed Fowler told him. “But batting is your hold. Keep on practicing with the stick. It will get you more money.”3 Freeman pitched for Wilkes-Barre’s Eastern League squad in 1893 before moving on to Haverhill, Massachusetts, where in 1894 he destroyed the New England League in his first season as a full-time hitter. Buck won the batting title at .386, while clubbing 34 home runs (including four in one game) and driving in a whopping 167 runs. After a brief stint with Detroit in 1895, the latter half of that year found Freeman in Toronto, where he would spend four seasons. Buck’s “wicked bat made the hearts of the Eastern League pitchers quake with craven fear,” according to one reporter.4 The free-swinging Freeman slugged 20 homers for the Toronto Canucks in 1897 and a league-record 23 in 1898.

At the conclusion of the 1898 Eastern League season, Toronto manager Arthur Irwin took over as skipper of the NL’s Washington Senators. He took five of his best players with him to Washington, including Freeman, who was given a month to “make good” or be sent back to the minors. On September 14, after a seven-year absence from the major leagues, Buck made his National League debut and in his second at-bat, drove the ball deep into the right-field bleachers for his first major-league homer. Freeman impressed the Washington press corps by hitting the ball hard six times in eight at-bats during his debut doubleheader. “Freeman has a free, natural swing,” the Washington Post reported. “His position at the bat indicates a natural hitter.”5 Buck turned in a two-homer game five days later, and his .364 average and .523 slugging percentage during his 29-game trial eliminated any possibility of returning to Toronto.

Unlike almost every other hitter of the day, Freeman’s batting style was to swing from the heels, and for the fences. Umpire Pop Snyder compared Freeman’s batting approach to the pugilistic style of then-World Heavyweight Champion Bob Fitzsimmons. “When Fitz drives one of his pile-driver favorites into the enemy the blow is supported by the force of the body,” Snyder said in 1898. “Freeman seems to push his full weight against the ball… he meets the ball about half way in a well-gauged, sweeping stroke. But his knack of meeting the ball is supported by a keen, correct eye for judging the angles.”6 Freeman, an amateur boxer himself, was no doubt flattered by the comparison to the heavyweight champ.

In 1899 Freeman became the talk of baseball, clouting an unheard-of 25 home runs in his first full major-league season. He also batted .318, slugged 25 triples, scored 107 runs while driving in 122, and even stole 21 bases during what still stands as one of the greatest rookie seasons in baseball history. Reds manager Buck Ewing called the rookie “one of the greatest batsmen that ever came into the League.” John McGraw publicly lusted after Freeman’s services, calling him “the best developer of heart disease among pitchers.” Meanwhile, Irwin, Freeman’s manager, claimed that half of Buck’s homers had come on hit-and-run plays, and praised him as “one of the best natural batsmen I have ever seen.” Not everyone was so pleased, however. The 1900 Spalding Guide virulently denounced Freeman without ever mentioning him by name, excoriating “sluggers” whose “sole object was to hit it out of sight.” The Guide concluded that a good slap hitter was “worth a dozen of your common class of home-run hitters.”

Although the Washington Post predicted that “his triumph at skirting the bases for homers will stand as a red-letter record for many a season to come,” Freeman’s 25 round-trippers were not technically the major-league record.7 In 1884, Chicago’s Lakefront Park boasted distances of 180 feet to the left-field fence and 196 feet to right. Four White Stockings took advantage of these cozy dimensions to post 20-homer seasons, led by Ed Williamson with 27. Until 1899, they were the only four 20-homer seasons in major-league history, and because of their illegitimate nature, Freeman’s mark of 25 in 1899 was widely considered the standard until Babe Ruth arrived.

Freeman didn’t need short porches to pad his home-run totals; he was noted for holding distance records at several different ballparks. In 1899, Buck slugged what Ned Hanlon and others described as the longest home run ever hit at Brooklyn’s Washington Park. “The ball sped far over a canvas awning in the right center corner of the lot,” the Washington Post reported, “and was picked up by a small boy on the opposite side of the street, in front of a row of tenement houses half a block from the grounds.”8 Although Freeman claimed the pitch was eight inches outside, he still had enough plate coverage to pull it to deepest right field. Meanwhile, in Louisville that year, a Freeman drive hit the wall of a distillery 50 feet behind the outfield fence. In Washington, he smashed two opposite-field drives off the distant left-field scoreboard. On August 20, 1903, Freeman became the first man ever to hit the ball completely out of Chicago’s South Side Park. And at Philadelphia’s Columbia Park, he once hit a ball so far that it reportedly sailed out of the stadium, over several houses, and through an open second-story window.

As part of the National League’s contraction from 12 teams to eight before the 1900 season, the Washington club went out of business. On February 9, 1900, owner J. Earl Wagner sold off eight of his best players, including Freeman, Bill Dinneen, and Shad Barry to the Boston Beaneaters for $8,500. Freeman, who made a point of never engaging in holdouts, immediately agreed to a $2,000 contract with Boston for 1900. Even the Boston papers called Washington’s dumping of Freeman and the others “the rankest offense ever perpetrated on a sport-loving public.”9

Freeman batted a solid .301 in 1900, but did not get along with Beaneaters manager Frank Selee, who, like the Spalding Guide, abhorred Buck’s power-hitting ways. “I know the Boston public like to see Freeman in the game, as he is likely to hit the ball very hard at times,” Selee said. “But this style of play is not a winner, for when Freeman is dangerous the pitchers keep the ball away from him, and his hitting counts for little. He is a poor fielder, thrower, and base runner.” Although previous observers in Washington had called Freeman’s outfield defense “above average,” Selee’s comments were the start of a bad defense rap that would follow Freeman the rest of his career. Meanwhile, Boston’s season spun out of control, with the franchise posting its first losing season in 14 years. “The Boston team is now playing every man for himself, and floundering about like a ship without a rudder,” Tim Murnane wrote in the Boston Globe.10 The “Napoleon-like” Selee pounced upon Freeman as a scapegoat, leaving him off the traveling squad for a late-season road trip and insulting him in the press: “I have often thought of playing [Freeman] at first and trying [Fred] Tenney in the outfield,” Selee said, “but brains are needed in the infield.”11

It was no surprise, then, that Freeman chose to jump to the fledgling American League in 1901 rather than play for a manager who openly despised him. In March, Buck signed a contract with the Boston Americans and rebounded to have one of his best seasons, ranking third in the AL batting race at .339 while finishing second to Nap Lajoie in homers (12), RBIs (114), and slugging percentage (.520). Freeman also contributed several game-winning hits in the ninth or extra innings, helping the Americans to a second-place finish in their inaugural season. Freeman posted equally strong numbers in 1902, finishing second with 11 homers while leading the AL in extra-base hits (68) and RBIs (121).

Ballplayers of Freeman’s day shunned conditioning and weight training, often believing that it would make them muscle-bound and restrict their movements. “The successful ballplayer never hardens his muscles,” Ty Cobb wrote in 1913. But Freeman was a notable exception. Indeed, he was a forerunner of the power-hitting workout gurus of the 1990s. A dedicated member of the local gym in his offseason home of Wilkes-Barre, Freeman kept himself in shape by walking 12 miles a day in addition to weightlifting, parallel bars, boxing, and other activities. “What work I have done as a batsman I owe in large measure to my exercise in the gymnasium,” Freeman said, “which… developed the muscles that come into play when I hit the ball.”12

Freeman also carefully studied the mechanics of hitting, adapting his stance to get as much of his weight behind the swing as possible. “I gather myself for a swing, and, as a rule, take a forward step in order to place myself at such an angle that the whole weight of my body moves at once in the same direction as the bat.”13 This approach to hitting was enhanced when Freeman began playing for Irwin, who spent long hours in Toronto teaching the dead pull hitter how to hit for power to the opposite field. Freeman was also an expert at intentionally fouling off pitches he didn’t like – a practice which, though commonly accepted today, was illegal during Buck’s career. On August 15, 1899, umpire Hank O’Day enforced the little-used rule against Freeman, calling a strike against him (foul balls did not yet count as strikes) for intentionally fouling off a Cy Young pitch.

In 1903 Freeman was the best hitter on Boston’s World Championship team, winning his second consecutive RBI title with 104 while also pacing the league in home runs (13), extra-base hits (72), and total bases (281). He thus became the first hitter ever to lead both the National and American leagues in home runs, later to be joined by Sam Crawford, Fred McGriff, and Mark McGwire. That October, Freeman played a key role in helping Boston win the inaugural World Series, batting .290 with three triples in the eight-game Series. Freeman continued to bludgeon opposing pitchers in 1904, leading the league with 19 triples while finishing second in RBIs (84) and tying for second in homers (7).

In 1905, however, the 33-year-old Freeman slipped dramatically, his batting average dropping 40 points to .240, while he failed to finish among the league leaders in home runs for the first time since 1898. In 1905 he also ended his impressive streak of playing 541 consecutive games and 5,431 consecutive innings, the latter a record which would stand until broken by Cal Ripken in 1985. In 1906 Freeman’s downhill slide continued, as he posted a .302 on-base percentage with only one homer in 436 plate appearances. When Freeman started off the 1907 season 2-for-12, Boston gave up on him, selling him to the Washington Senators on April 24 for the waiver price of $1,000. But four days later, before Freeman played in a single game for Washington, the Senators sold him to Minneapolis.

Although the origin of his nickname is unknown, Freeman’s popularity was such that later players with that surname were automatically dubbed “Buck”. “Some day – but not in our generation,” Baseball Magazine wrote in 1913, “it will be possible for a man named… Freeman to escape being called ‘Buck.’”14 This phenomenon proved especially confusing in 1907, when there were three Freemans on the Minneapolis Millers, with the others dubbed “Buck II” and “Buck III” by the press. But the original Buck separated himself from the crowd, posting a .335 average while taking advantage of Nicollet Park‘s 279-foot right-field fence to set a new American Association record with 18 homers. Freeman returned to Minneapolis in 1908, but his season ended in late July when he dislocated his right shoulder sliding into home plate. Despite playing only half a season, his ten homers were still good enough to tie for the league lead.

Freeman recovered from the injury to serve as a player-manager in the outlaw Susquehanna League in 1910 and 1911, and in 1913 he embarked on a lengthy minor-league umpiring career. After a game on August 9, 1913, the rookie arbiter was mobbed by 2,000 angry fans in Wilmington, Delaware. As a squad of a dozen policemen rushed him off the field, Buck was pelted with a hail of stones and bricks, several of them hitting him on the head. With Freeman still under police escort, the mob trailed him from the ballpark to a local saloon and then a trolley stop, where Freeman was finally able to board a car and escape safely. Unbowed by the riot, Freeman umpired for the next 13 years in the Tri-State League, Canadian League, International League, American Association, and even, apparently, a brief stint in the Negro Leagues. (An umpire named Buck Freeman is known to have worked the 1924 Negro League World Series. Since Freeman was an active minor-league ump at the time, and since the Negro Leagues used white umpires then, it was almost certainly the same Buck Freeman.)

During his offseasons, though he didn’t need the money, Freeman kept in shape by working as a stoker in the boiler room of a local silk mill. He spent much of his time cockfighting, and became well known as a breeder of fighting birds, keeping a flock of more than 100 gamecocks in his barn. Even a 1937 police raid on a cockfight at Freeman’s home did not deter him. “I’d walk 20 miles to see a good cockfight,” he once said.15 In October 1906, Freeman purchased the New Haven Blues of the Connecticut League; by 1910 the team had been renamed the Prairie Hens. After his retirement from umpiring, Freeman scouted for the St. Louis Browns from 1926 to 1933, then managed an outlaw team in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania, for two years. After the 1935 season Freeman retired to the modest hillside home in the Georgetown section of Wilkes-Barre where he resided with his wife, the former Annie Kane (whom he had married in 1895), and their six sons. A well-known local institution, Freeman enjoyed regaling youngsters with tales from his playing days. “In Wilkes Barre he was just like Babe Ruth,” one of those youths recalled years later. “Every kid in town knew him.”16 Buck Freeman died of a stroke in Wilkes-Barre on June 25, 1949, at age 77. He is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in nearby Shavertown.

An updated version of this biography appeared “New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans,” edited by Bill Nowlin (SABR, 2013). The biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006), edited by David Jones.

Sources

Scott Labenski. Unpublished biographical sketch of Buck Freeman. 2004.

Boston Globe

Chicago Tribune

New York Times

Sporting Life

Washington Post

Notes

1 Washington Post, October 2, 1899.

2 Washington Post, October 15, 1899.

3 Ibid.

4 Washington Post, September 14, 1898.

5 Washington Post, September 15, 1898.

6 Washington Post, October 3, 1898.

7 Washington Post, October 2, 1899.

8 Washington Post, October 19, 1899.

9 Washington Post, February 12, 1900.

10 Boston Globe, October 5, 1900.

11 Washington Evening Star, October 12, 1900.

12 Washington Post, October 15, 1899.

13 Washington Post, October 15, 1899.

14 William A. Phelon, “The Decline and Fall of the Left Handed Batter,” Baseball Magazine, July 1913.

15 Scott Labenski, “Buck Freeman bio,” unpublished biographical sketch of Buck Freeman. 2004.

16 Ibid.

Full Name

John Frank Freeman

Born

October 30, 1871 at Catasauqua, PA (USA)

Died

June 25, 1949 at Wilkes-Barre, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.