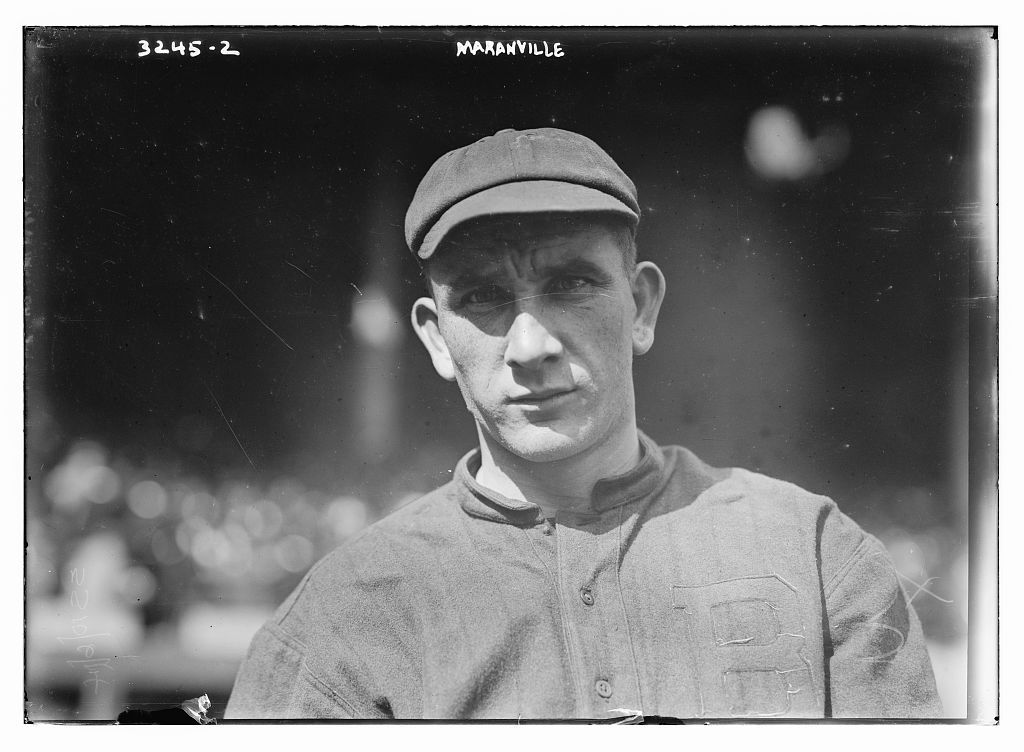

Rabbit Maranville

Standing only 5’5″ and weighing a good deal less during the Deadball Era than his listed playing weight of 155 lbs., Rabbit Maranville compiled a lifetime batting average of just .258 and is known as much for his zany escapades and funny stories as for anything he accomplished on the diamond, but his outstanding glove work kept him in the big leagues for 23 seasons and eventually earned him a plaque in Cooperstown. “Maranville is the greatest player to enter baseball since Ty Cobb arrived,” said Boston Braves manager George Stallings. “I’ve seen ’em all since 1891 in every league around the south, north, east, and west. He came into the league under a handicap—his build. He was too small to be a big leaguer in the opinion of critics. I told him he was just what I wanted: a small fellow for short. All he had to do was to run to his left or right, or come in, and size never handicapped speed in going after the ball.”1

Standing only 5’5″ and weighing a good deal less during the Deadball Era than his listed playing weight of 155 lbs., Rabbit Maranville compiled a lifetime batting average of just .258 and is known as much for his zany escapades and funny stories as for anything he accomplished on the diamond, but his outstanding glove work kept him in the big leagues for 23 seasons and eventually earned him a plaque in Cooperstown. “Maranville is the greatest player to enter baseball since Ty Cobb arrived,” said Boston Braves manager George Stallings. “I’ve seen ’em all since 1891 in every league around the south, north, east, and west. He came into the league under a handicap—his build. He was too small to be a big leaguer in the opinion of critics. I told him he was just what I wanted: a small fellow for short. All he had to do was to run to his left or right, or come in, and size never handicapped speed in going after the ball.”1

The third of five children, Walter James Vincent Maranville was born on November 11, 1891, in Springfield, Massachusetts. His mother was Irish but his father and the Maranville name were French. Walter (then known as “Stumpy” or “Bunty”) attended the Charles Street and Chestnut Street grammar schools and played catcher during his one year at Technical High. His father, a police officer, allowed him to leave school if he apprenticed for a trade, so at age 15 he quit to become a pipe fitter and tinsmith. To his father’s dismay, Walter devoted less attention to his apprenticeship than he did to baseball. He was playing shortstop for a semipro team in 1911 when Tommy Dowd, manager of the New Bedford Whalers of the New England League, signed him to a contract for $125 per month. The 19-year-old shortstop batted .227 and committed 61 errors in 117 games.

It was at New Bedford in 1912 that Maranville acquired his distinctive nickname. Some sources say that it came from his protruding ears, but he told a different story: “I was very friendly with a family by the name of Harrington. One night I was down to their house having dinner with them when Margaret, the second oldest daughter, asked me if I could get two passes for the next day’s game, as she wanted to take her seven-year-old sister to see me play. I said, ‘Sure, I’ll leave them in your name at the Press Gate.’ She said, ‘And come down to dinner after the game.’ I left the two passes as I promised and after the game I went down to their house for dinner. I rang the door bell and Margaret came and opened the door and said, ‘Hello Rabbit.’ I said, ‘Where do you get that Rabbit stuff?’ She said, ‘My little seven-year-old sister (Skeeter) named you that because you hop and bound around like one.’”2

Maranville improved his batting average to .283 during his second year at New Bedford, and the Boston Nationals purchased his contract for $1,000. Reporting to the club on September 4, Rabbit got into 26 games and made 11 errors while batting .209. “The fall of 1912 my fielding was above the average, but my hitting was not so good,” he recalled. “However, I was the talk of the town because of my peculiar way of catching a fly ball. They later named it the Vest-Pocket Catch. Boston wasn’t drawing any too good, but it seemed like everyone that came out to the park came to see me make my peculiar catch or get hit on the head.”3 Maranville settled himself under pop-ups with what seemed to be total unconcern, arms at his side; as the ball plummeted towards earth, apparently ignored, he suddenly brought his hands together at waist level and let the ball fall into the pocket of his glove. “Many of the players passed different remarks about my catch which wouldn’t go in print,” Rabbit said. “I do, however, remember what Jimmy Sheckard said: ‘I’ll bet you he don’t drop three balls in his career, no matter how long or short he may be in the game. Notice the kid is perfectly still, directly under the ball, and in no way is there any vibration to make the ball bounce out of his glove.’”4

At training camp in the spring of 1913, new manager George Stallings scheduled two-a-day practices, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. “The players would dress after the first workout and return to the hotel where they’d loaf for an hour or so,” Rabbit recalled. “Seizing the opportunity that was before me, I got a dozen kids to pitch to me before the next session, sometimes to the point that I was groggy.”5 Despite his hard work, Maranville still couldn’t crack the starting lineup. “Coming from the park after our afternoon session, I was walking with a big first baseman by the name of Gus Getz. He said, ‘Rabbit, did you see where they have the ballclub picked?’ I said, ‘No, who have they decided on for shortstop?’ He said, ‘Art Bues, Stallings’ nephew.’ I said, ‘If I couldn’t play ball better than that guy I’d quit.’ Walking behind us was Stallings, and he overheard what I said unbeknown to us. That evening after dinner I was loafing around the lobby of the hotel when Stallings came along and said, ‘I want to talk to you.’ We went over to a sofa and sat down. Stallings said, ‘You don’t like my selection of Bues for shortstop over you.’ I said, ‘No, I don’t.’ ‘Well,’ Mr. Stallings said, ‘you have a lot to learn and I’m running this club and I’ll make my own selections no matter what you or anybody else thinks.’ I said, ‘That’s okay with me; I’m not trying to run your ballclub, but if I’m not a better ballplayer than that relative of yours, I’ll quit.’ He said, ‘No, you will not; I’ll keep you until we get back to Boston, then use you in a trade if I have the opportunity.’”6

Maranville sat the bench during the 1913 exhibition season until the Braves arrived in Atlanta on Easter Sunday. After going to church that morning, he put on his uniform in his hotel room and boarded the team bus. “Going up Peach Tree Boulevard on our way to the park, a player who I don’t remember right off hand told me I was to play shortstop that afternoon as Bues came down with a sore throat,” Rabbit recalled. “We left Bues in Atlanta as he was a very sick boy and came into New York to open the season with the Giants. Game time came along and Stallings yelled down the bench at me, ‘Rabbit, you’re playing shortstop today.’ I said, ‘Yes, and you will never get me out of there.’”7 Maranville picked up three hits against Christy Mathewson on Opening Day as the Braves won, 8-3. He went on to hit .247 in 143 games that season and remained the regular shortstop for Stallings’ entire tenure in Boston.

Maranville appeared in all 156 games during the miracle season of 1914, driving in 78 runs out of the cleanup spot even though he batted only .246. He came up with many big hits during the Braves’ pennant drive, but none was more important than the game-winning home run he belted in the tenth inning on August 6—even though he was suffering from a severe hangover from drinking too much champagne at a dinner party the night before. “In the clubhouse while I was undressing Stallings came over to me and said, ‘You go back to choking up; you are no home-run hitter,’” Rabbit remembered. “Truthfully, I never did see the ball I hit, and years later Babe Adams, who was the pitcher that day, asked me if it was a curve or a fastball I hit over the fence. I told him I never saw it and he said, ‘I know darn well you never did.’”8

Maranville’s greatest contributions, of course, came with the glove. Boston had purchased second baseman Johnny Evers from the Chicago Cubs during the previous winter, and he and Rabbit gave the Braves the best middle infield in baseball. Though no sportswriter ever penned a poem about Maranville-to-Evers-to-Schmidt, that combination turned far more double plays in 1914 than Tinker, Evers, and Chance ever did in any one season. “It was just Death Valley, whoever hit a ball down our way,” Rabbit recalled. “Evers with his brains taught me more baseball than I ever dreamed about. He was psychic. He could sense where a player was going to hit if the pitcher threw the ball where he was supposed to.”9

Evers’ omniscience paid off in a big way during Game Two of the World Series. Heading into the bottom of the ninth, the Braves led, 1-0, but the Athletics had men on first and second and only one out. The batter was Eddie Murphy, a fast left-handed hitter who Maranville claimed hadn’t hit into a double play all season. Rabbit was already playing only 10 feet from second base, but Evers looked over and told him to move closer. The young shortstop followed orders, moving only five feet from the bag. Bill James was about to deliver his pitch when Evers called time and instructed Rabbit to move even closer. Maranville moved within one yard of second base. On James’ first pitch, Murphy hit a rifle shot between the pitcher’s legs. Rabbit was practically standing on second when he fielded the grounder and fired the ball to first to complete a game-ending double play. “If it hadn’t been for Evers insisting I play closer to second base, I would never have made the play, which seemed almost impossible to make from the spectators’ point of view,” he said.10

Evers and Maranville finished one-two in the 1914 Chalmers Award voting, and that off-season they were approached by Bill Fleming, a scout for the Federal League’s Chicago Whales. “We met him and he laid down $100,000 in front of Evers and $50,000 in front of me as a bonus with a three-year contract to play for the Chicago Feds,” Rabbit recalled. “Evers refused and so did I.”11 Maranville remained a fixture in the Braves infield for another six years, though he missed nearly all of 1918 when he enlisted in the Navy and served as a gunner aboard the USS Pennsylvania. On November 10, 1918, Rabbit told his shipmates that they would get big news the next day. “Everyone kept asking me what the big news was going to be,” he remembered. “I said, ‘Wait until tomorrow; I will tell you then.’ At 6:30 the next morning we got word that the armistice had been signed. That afternoon I was called in to the captain’s quarters. The captain said to me, ‘How is it you knew the armistice was going to be signed today? Who gave you that information?’ I said, ‘I didn’t know anything about the armistice being signed. The reason I said the big day is tomorrow and they would hear great news is that today is my birthday.’”12

In January 1921 the Braves traded Maranville to the Pittsburgh Pirates for Billy Southworth, Fred Nicholson, Walter Barbare, and a sum of money said to be $15,000. Rabbit remained with the Pirates through the 1924 season, giving them their first reliable shortstop since the retirement of Honus Wagner. He then spent one season with the Chicago Cubs, serving as player-manager for a short time, and another with the Brooklyn Dodgers, drawing his release in August 1926. A drunk by his own admission, Maranville was considered washed up as a big leaguer, but he swore off alcohol at Rochester in 1927 and returned to the NL in 1928 as the starting shortstop for the St. Louis Cardinals, appearing in the World Series and batting .308, the same average he had posted in the 1914 World Series. Over the caption “Rab’s Top Fan,” the New York Journal-American ran a photograph of Rabbit’s father with his arm around his son, wearing a look of genuine pride on his face.

Maranville returned to Boston in 1929 for a second stint with the Braves, playing regularly at shortstop for three years and second base for two. Legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice thought of Rabbit at that point in his career “as the link between the old days and the new in baseball. He broke in with the hard-bitten crew in Boston and wasn’t exactly a sissy, reveling in the atmosphere in which he found himself. For years he was a turbulent figure on the field, fighting enemy ball players and umpires—and even the players on his own team when he found it necessary.”13 Then in his early 40s, Maranville still played with the same old hustle, and it ultimately caused the end of his major-league career. In a 1934 spring exhibition against the Yankees, with Boston down by a run, Rabbit attempted to score even though the catcher was blocking the plate. When the dust finally cleared, Maranville lay in agony, a bone jutting out of his ankle. “Out!” roared the umpire. Rabbit reportedly pointed to his limp foot resting on the edge of the plate and said, “You see where that foot is, don’t you?”14 He then passed out.

After missing the entire 1934 season, Maranville tried to come back in 1935 but played only 23 games before giving up. “For a quarter of a century I’ve been playing baseball for pay,” he wrote in 1936. “It has been pretty good pay, most of the time. The work has been hard, but what of it? It’s been risky. I’ve broken both my legs. I’ve sprained everything I’ve got between my ankles and my disposition. I’ve dislocated my joints and fractured my pride. I’ve spent more time in hospitals than some fellows ever spend in church. I’ve ridden on railroad trains until a steam shovel couldn’t lift the cinders I’ve combed out of my hair. I’ve eaten lousy food and slept on lousy beds. I’ve been socked with fists and pop bottles and insults. I’ve been awakened out of bed in the middle of the night by fat-headed bums who only wanted to know what Pop Anson‘s all-time batting average was. I’ve lost a lot of teeth and square yards of hide. But I’ve never lost my self-respect, and I’ve kept what I find in few men of my age—my enthusiasm.”15

Maranville managed at Elmira in 1936, Montreal in 1937, Albany in 1939, and back home in Springfield in 1941. When he finally left Organized Baseball for good, he worked for youth baseball programs in Rochester, Detroit, and finally New York City. As director of the New York Journal-American sandlot baseball school after World War II, Rabbit taught thousands of kids how to play the game in clinics at Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds. Among his pupils were future big leaguers Whitey Ford, Bob Grim, and Billy Loes.

Rabbit Maranville died at age 63 of coronary sclerosis on January 5, 1954, just a few weeks before his election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He is buried in St. Michael’s Cemetery in his hometown of Springfield.

A version of this biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Potomac Books, 2004), edited by Tom Simon. It is also included in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Related link: Download your free e-book copy of Run, Rabbit, Run: The Hilarious and Mostly True Tales of Rabbit Maranville

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 “Maranville Best Shortstop,” September 1914 newspaper interview with George Stallings.

2 “Springfield’s Rabbit,” Springfield Republican, August 5, 1979.

3 Citation from unknown source, in Maranville’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

4 Walter “Rabbit” Maranville, Run, Rabbit, Run (Phoenix, AZ: Society for American Baseball Research, 2011), 13.

5 “The Credo of Maranville,” St. Louis newspaper (newspaper unknown), August 3, 1933. Located in Maranville’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

6 Maranville, Run, Rabbit, Run, 14.

7 Maranville, Run, Rabbit, Run, 15.

8 Maranville, Run, Rabbit, Run, 22.

9 Maranville, Run, Rabbit, Run, 16.

10 Citation from unknown source, in Maranville’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

11 “Springfield’s Rabbit,” Springfield Republican, August 5, 1979.

12 Maranville, Run, Rabbit, Run, 41.

13 Grantland Rice, unattributed newspaper column, January 1937.

14 “Maranville Mourned As Hustler and Scrapper,” January 6, 1954. Located in Maranville’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

15 Rabbit Maranville, “Hot Stove Stuff,” American Legion Monthly, No. 11, January 1926.

Full Name

Walter James Vincent Maranville

Born

November 11, 1891 at Springfield, MA (USA)

Died

January 5, 1954 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.