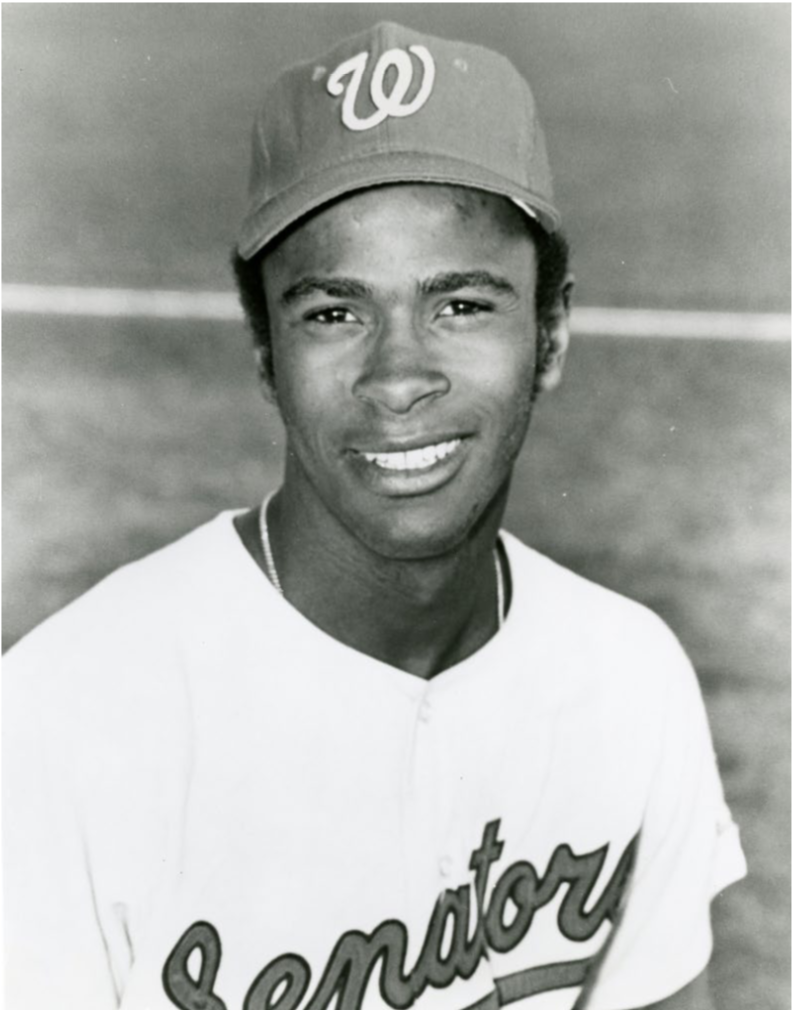

Tom Ragland

“Always smiling, made you feel good to be around him.”

Cleveland sportscaster Joe Tait on Tom Ragland.1

Tom Ragland wanted his mother to get him a baseball glove when he was 5 years old. There was no money for one, and it was a few years later when he found a discarded one on a Detroit street. For a boy who would be picking cotton when not in school, nothing ever came easy for Tom Ragland. He knew what it took to persevere. His journey to the major leagues took six years of bus rides in the minors, and once he made it to the top he mostly sat on the bench waiting for his opportunities. Ragland played 10 seasons of professional baseball, but in only one of them was he solely on a major-league roster. He played in only 102 games at the major-league level, including 25 with the 1972 Texas Rangers. The boy who found, cleaned, and stitched up his first glove after finding it on the street became a man called “Rags” who used his grit and glove to make it to the major leagues.

Tom Ragland wanted his mother to get him a baseball glove when he was 5 years old. There was no money for one, and it was a few years later when he found a discarded one on a Detroit street. For a boy who would be picking cotton when not in school, nothing ever came easy for Tom Ragland. He knew what it took to persevere. His journey to the major leagues took six years of bus rides in the minors, and once he made it to the top he mostly sat on the bench waiting for his opportunities. Ragland played 10 seasons of professional baseball, but in only one of them was he solely on a major-league roster. He played in only 102 games at the major-league level, including 25 with the 1972 Texas Rangers. The boy who found, cleaned, and stitched up his first glove after finding it on the street became a man called “Rags” who used his grit and glove to make it to the major leagues.

Thomas Junior Ragland was born on June 16, 1946, in Talladega, Alabama. His parents, Thomas Garrett and Catherine Ragland, never married, and young Thomas split his childhood between Alabama with his sharecropper maternal grandparents and Catherine, who lived in Detroit. He had several half-brothers and half-sisters. He also for a time lived in Cleveland with an aunt, Claudia Borden, who “helped raise me and was a great influence in my life.”2 When he was 5 years old, Ragland, living in Alabama, asked for a baseball glove for Christmas. His grandmother “almost had a stroke,” Ragland recalled. In Alabama, he lived in his grandparents’ house with about 15 others. A baseball glove was a pure luxury. “I needed clothes,” Ragland said, acknowledging that that was the common item on their Christmas list. “To want a baseball glove at five years old,” he laughed. “I was born to do it.”3

His surroundings in Alabama were devoid of baseball. The family would sit in the living room, some playing dominoes or checkers, but he was up close to the radio, listening to a ballgame with his grandfather. He remembered hearing Washington Senators games and Mickey Vernon playing.4 When Rags found that glove on a Detroit street, he was living with his mother and stepfather. He attended Breitmeyer and Sherrard, two Detroit elementary schools. Because of an abusive situation involving his stepfather, Ragland lived in Detroit and then Gadsden, Alabama. “I was living with my mother and stepdad, who was a real bad person to me and my mother,” Ragland recalled. Then came a moment that changed his life forever. Jim Bibbs, Ragland’s elementary-school gym teacher, had already been a godsend to Ragland, paying his travel when he needed to leave home for Detroit and Gadsden. This time, Bibbs sent him $25 for Christmas, a gift that came with a choice. The $25 could be used to get himself something nice for Christmas, or it could buy a bus ticket back to Detroit. Bibbs offered to let Ragland live with him while finishing his junior and senior years of high school, and also play baseball. Ragland bought the bus ticket, and Bibbs got him a spot in a Babe Ruth League. Ragland was grateful. Bibbs “always put me in the right spot,” he said. “He became my dad.” In high school, Ragland was the MVP of the league in both his junior and senior years, leading Northern High School to back-to-back East Side championships in 1964-1965.5 Bibbs went on to become a track coach at Michigan State, the first African-American coach in the university’s history. He was inducted into the Michigan State Athletic Hall of Fame in 2010, and the Track & Field and Cross Country Coaches Hall of Fame in 2015.6 “I know that God sent Mr. Bibbs to me,” Ragland said. “Mr. Bibbs is a living angel.”7

Ragland was discovered by Charles “Tommy” Thompson, a scout for the Washington Senators. After graduating from high school, he was drafted by the Senators in the 15th round of the inaugural June 1965 amateur draft. With his $4,500 signing bonus, Ragland showed his thankfulness by sending $1,000 to his mother and buying his grandparents a car. He offered money to Bibbs, who refused, “but he told me to help another kid whenever I got the chance.”8 He took his first airplane ride in July, landing in Virginia, where he began his professional career with the Wytheville Senators of the Rookie Appalachian League. Ragland batted an impressive .301 and his 17 doubles tied him for second in the league. He hit eight home runs, two in one game, and played 53 games at shortstop with a .925 fielding percentage, best among shortstops.9 He also tied for the league lead in being hit by a pitch (6). Ragland was surprised at the amount of segregation and racism he saw that existed not only in the South, but also within baseball teams themselves. Ballplayers on the same team were segregated according to hotel accommodations. “I discovered how ugly things were,” Ragland said. “I didn’t realize how things were like that in baseball. I thought it would be different in the pros.”10

In 1966, Ragland moved up to the Geneva (New York) club in the Class-A New York-Pennsylvania League. Manager Gordon MacKenzie reported in April that Ragland “is a good hitter and he shows some power. He improves every time I see him play second base. He’s got a good flip motion on his throws which should help him make the tough plays.”11 Ragland batted only .216, but in 123 games at second base, his .969 fielding percentage, putouts (254), and assists (285) were tops in the league for second basemen. Ragland represented Geneva at the league’s all-star game in July.12 At the last home game of the season, he was presented with a suitcase for winning the fans’ vote as the most popular player on the team.13 Even more impressive for Ragland was that his hero, Pete Rose, had won the award in 1960. “Pete Rose was my idol. I loved Pete Rose. I still do.”14

Ragland would need that suitcase in 1967. On January 28, he wed Ida Mae Goldman. He began the season with the Burlington (North Carolina) Senators of the Class-A Carolina League. Ragland continued to find discrimination, as white players on the Burlington team were able to stay in a nice trailer park, while he and Ida had to rent a room from a high-school principal. He called this the “tail end” of the days of Jim Crow and segregation.15 He batted .237 in 49 games, 39 of them at shortstop with a fielding percentage of .916. Geneva tried several players at second as a replacement for Ragland but was unsuccessful, so they reacquired him from Burlington at the end of July.16 “I like it here,” Ragland said of playing in Geneva.17 After the season, the Raglands had an addition to their family, as daughter Althea was born.18

In 1968 Ragland remained at the Class-A level, playing for High Point-Thomasville (North Carolina), managed by Jack McKeon, in the Carolina League. Ragland showed his durability by leading the league in games played (141) and was second in being hit by a pitch (10). He batted only .240 but led all second basemen in putouts (355) and in turning double plays (98). “We finished second in our division, then won five straight in the playoffs,” Ragland remembered of the championship club.19 That winter, Ragland spent time in Bradenton, Florida, with the Senators team in the Florida Instructional League.

Ragland made the jump to Buffalo of the Triple-A International League in 1969, despite the original plans that he would remain in Double A. That all changed when Washington manager Ted Williams paid a visit to the minor-league camp. Williams “saw me hit a double off the Tigers’ Triple-A team. He told the farm director Hal Keller to play me at second base for Buffalo,” Ragland remembered.20 “Tom Ragland didn’t figure very prominently in the Bisons’ 1969 plans when spring training opened,” wrote Joe Alli of the Buffalo Courier-Express, “but the 22-year-old second baseman is attracting a lot of attention with his excellent play in exhibition games.”21 Ragland was batting .368 near the end of March and manager Hector Lopez was impressed. “That boy Ragland is doing a good job,” he said. “He handles the bat pretty good, can run, and makes the plays in the field.”22 In game one of an Opening Day doubleheader, he batted in the top of the ninth at Louisville with the bases loaded and the score 3-3. He looped a single to center, driving in the go-ahead run in what would become an 11-3 laugher for Buffalo. “I want to tell you I was nervous when I went to the plate,” Ragland admitted. “When I reached first base I said, ‘Thank you, Lord!’”23 The hit calmed his nerves and he doubled and singled in his first two at-bats in the second game.

In Buffalo’s home opener, Ragland smashed a three-run home run. “He’s our second baseman until he plays himself out of a job,” Lopez promised.24 Ragland went 3-for-5 on his 23rd birthday to lead Buffalo to a 7-3 win.25 His biggest contribution, however, was his steady play at second. “Ragland isn’t hitting as much as some of the other second baseman,” Lopez said, “but he makes the double play better than anyone in the league.”26 Ragland led the team in stolen bases (13), walks (65), games (135), and plate appearances (521), and was second in runs scored (57). He led all second basemen in the International League in assists and double plays, and tied for the league lead in putouts. He batted .252 with 3 home runs and 40 RBIs. Ragland left a game on May 8 and raced to the hospital, where Ida gave birth to their second daughter, Kimberly.27 He returned to Florida at the end of the season and played again in the Instructional League.

In 1970 Ragland played for the Senators’ Triple-A farm team, the Denver Bears of the American Association. He again led his team in games played (126) and in plate appearances (503), and was second in walks (61) and doubles (19). He had a .979 fielding percentage at second base, and also played some at shortstop and helped turn 75 double plays. His 10 hit-by-pitches led the league again. He batted .259 with 2 home runs and 40 RBIs. His pinch-hit bases-loaded double in the ninth powered Denver to a win over Wichita on May 25.28 Denver won the Western Division title and met Omaha in the playoffs. Ragland doubled in a five-run first, then doubled home two in a Game Four 8-3 win.29

After six years of toiling in the minor leagues, Ragland made it to the Senators out of spring training in 1971. A veteran power hitter who stood 6-feet-7 made sure the young, light-hitting 5-foot-10 Ragland was taken care of in this new experience. “He’s just the greatest person in the world,” Ragland said of his towering yet compassionate teammate, Frank Howard. “When I first came north, he took me aside. He said, ‘Rags, listen to Hondo. For the next two weeks, wherever Hondo goes, you go. Whatever Hondo eats, you eat. It takes two weeks for the first paycheck. I know you’re not making any money.’ He carried me for two weeks. I’ll never forget him for that.”30

Ragland made his major-league debut on Opening Day, April 5, 1971, as a defensive replacement at second base. It was the Senators’ final Opening Day. He handled two putouts in the 8-0 win over Oakland, but did not get an at-bat. “I finally made it to the show,” he recollected in 2005. “To hear that national anthem, that was just awesome.”31 He entered three more games as a late-inning replacement, going hitless in two at-bats. He was optioned to Denver on April 20 when Don Wert came off the disabled list.32

Denver won the American Association title in 1971. Ragland contributed by slamming an inside-the-park home run in the ninth inning in a 3-2 win over Omaha on May 27.33 He doubled in the winning run in the bottom of the ninth in a 6-5 win on July 25.34 The Bears trailed Indianapolis three games to two in the best-of-seven championship series. The final two games were a doubleheader at Denver’s Mile High Stadium. Ragland went 2-for-3 in the first game, a 4-2 victory.35 Denver won the second game, 5-2, to take the title and move on to the Junior World Series, which they lost to Rochester (New York). He finished the season batting .301 with 4 home runs and 32 RBIs. He also had a strong .986 fielding percentage at second base. Ragland briefly played winter ball in Venezuela for the Zulia team, but was released during their season.36

Ragland was recalled to Washington for the final games of the season. These were the final games played by the expansion Senators franchise that began in Washington in 1961, and the end of the 71-year history of the combined teams known as the Washington Senators. The original Senators (1901-1960) left for Minneapolis, and this team was now headed to Arlington, Texas. Ragland’s first game back was a start in Boston on September 24. Batting eighth and playing second base, he singled off Roger Moret to get his first major-league hit. On September 30, Ragland started at second base in the last game of the Senators’ franchise. He went 1-for-4 and scored a run in the eighth inning that would be the last run scored in Washington for a long while. The run gave Washington a 7-5 lead, but because fans stormed the field in the top of the ninth, the game was forfeited to the New York Yankees. The statistics counted, except that there were no winning or losing pitchers. Ragland finished with a .174 batting average with four singles in 10 games.

While the Senators moved to Texas and became the Rangers, Ragland, after spending spring training with them, went back to Denver to start the season. “Ted [Williams] was big on experience,” Ragland said, noting that the Texas manager felt there were too many right-handed hitters on the team.37 In 88 games with Denver, he batted .245 with 6 home runs and 38 RBIs. On July 23, Ragland was recalled by the Rangers. Because he was called up after the All-Star break, he didn’t receive a $5,000 bonus he had been hoping for. From July 27 to August 22, he started four games and finished five others, going 0-for-16 at the plate. “But in those four (starts) I faced Vida Blue, Wilbur Wood, Dave Lemonds, and Ken Holtzman. I got a few hits after that and they started to fall in a little better.”38 He had a nine-game hitting streak from August 25 to September 5 in which he batted .357 (10-for-28) with a .400 on-base percentage. He finished the final seven games of the season 0-for-14 to drop his season average to .172. He had an impressive .982 fielding percentage, however, committing only one error in 89 innings.

Ragland’s time in the Washington/Texas organization came to an end after eight seasons. On November 30, 1972, he was traded to the Cleveland Indians for pitcher Vince Colbert. Assigned to Cleveland’s Triple-A team at Oklahoma City, he was invited to spring training as a nonroster player. A .303 batting average won him a spot on the Cleveland roster, which impressed manager Ken Aspromonte. “Tom has done everything we’ve asked of him,” the manager said. “I like the boy very much.”39 Ragland was overjoyed. “I don’t see how anybody could possibly be any happier than I am,” he said. “I appreciate this chance and I hope I can continue to please Kenny. I’ve worked hard and I’ll keep on working hard. This is what I’ve always wanted.”40 It also meant he finally received the $5,000 bonus, which the Raglands used to purchase a home in Detroit.41

Ragland didn’t get into a game until the first game of a doubleheader against Boston on April 22. He entered to play second in the eighth inning. With one on and one out, Cleveland trailed 7-4 in the bottom of the ninth. Ragland singled off John Curtis in his first at-bat of the year. After a walk loaded the bases, pitcher Ron Lolich hit a walk-off grand slam to win 8-7. In May, with Jack Brohamer injured, Ragland took advantage of more playing time, starting 19 games and batting .338 with a .373 on-base percentage. He went 3-for-4 in an 8-3 win at Chicago on May 25.

“I knew what Tommy could do because I saw him play for Denver in 1970 when I was managing Wichita,” Aspromonte said. “I figured he could provide us with back-up insurance at both second base and shortstop, but I never figured him for this.” The manager mentioned a time when he wanted to lift Ragland for a pinch-hitter and wanted to explain it to him. Instead, Ragland replied, “I’m just so grateful to you for bringing me up here and giving me this chance, you don’t have to explain anything to me. You’re tops and you do anything with me you think best.” Aspromonte said, “How can you beat a guy like that? He’s one in a million.”42

Ragland was reflective of how far he had come: “This is the first time in nine years of pro baseball that any organization or any person has shown any faith in me. Why shouldn’t I be very grateful? It’s also the reason I feel like I’ve got to go out there every day and prove myself over and over again … to justify that faith.”43 More than 40 years later he still had a special place in his heart for teammate Gaylord Perry, who thought Ragland was the best defensive infielder the Indians had. “If I’m pitching tomorrow,” Perry said, “I want Raggy at second base.”44

Ragland’s average plummeted through the rest of the season, however, from .347 on May 31 to .269 on June 30 as he went 3-for-32 over the month. Much of the blame could be placed on a hyperextended right knee as well as other bumps and bruises that he refused to let sideline him. “Rags is the guy who’s really hurting,” Aspromonte said. “He has a sore knee, back and arm, but never once did he ask to come out of the lineup. He’s the one who deserves credit.”45 When Jack Brohamer returned, Ragland’s playing time decreased, and so did his optimism. “When I was starting out in the minors,” he said, “it wasn’t sitting on the bench in Cleveland that I was dreaming of. It hurts, man, because I’ve proved I can do the job.”46 His final batting average was .257 with 12 RBIs, and his fielding was once again steady with a .984 fielding percentage.

Seeing little room for Ragland on the roster in 1974, Cleveland sold him to the Houston Astros for the $20,000 waiver price. Houston assigned him to Denver, now their minor-league affiliate.47 He played his fourth season in the familiar surroundings of Mile High Stadium, batting .249 with 3 home runs and 49 RBIs. Playing 120 games at second base, he had a .970 fielding percentage. It would be his final season, as the demotion to the minor leagues meant his salary was cut from $18,000 to $11,000 for the season. Denver offered him a contract. “I declined the contract, politely,” Ragland said. “I told them to give another kid a chance. My wife and I had our fourth child by then (in addition to Althea and Kimberly, the family also included a daughter, Katrina, and a son, Thomas Jr.). I was 28. I wasn’t ready to quit ball, but we had a mortgage payment and I had to provide for my family.”48 Ragland went home to Detroit and began working full-time at his offseason job: making ice cream at a Kroger milk-processing plant. He worked his way up to distribution manager.49 He also scouted in the Detroit area for the Rangers from 1977 to 1979. In 1999, after more than 20 years away from the game, Ragland decided to take a trip to spring training. “I had taken two weeks’ vacation and I was going to go to Florida and mingle, get my name back in the hat. Everybody in my family was grown. It was the right time to get back in the game.” While en route, however, he received word from back home that his son, Thomas Jr., was in critical condition following a car accident. Ragland returned home. His son died three weeks later. “It took me five years to get my cry out,” he said.50

Ragland said he still had a longing for baseball, and wished his career had taken a different path. “That’s my wish, that I could get back in the game again,” he said in 2005. “Not a week goes by that I don’t dream about baseball. It hurts sometimes.”51 Besides scouting for the Rangers, he also coached Little League and high-school baseball, including the St. Martin de Porres High School team that Thomas Jr. played for.52 Ragland also appeared with other former major leaguers in the Youth Baseball Clinic Series, sponsored by the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association. At one such gathering, organizer Jason Glasgow said, “We want to focus on the inner-city kids, because there’s not a lot of fields and coaches in Detroit, and we feel like the kids there are missing out on playing a great game.”53 Underprivileged kids can learn a lot from a guy named “Rags” who found his first glove on the street.

After 41 years working at Kroger, Ragland retired in 2009. He was humbled when company vice presidents attended his retirement ceremony. Many of them had tears in their eyes recalling the relationships they built with him over the years. “That made me feel good,” Ragland said.54

As of 2017 Tom and Ida Ragland had three grown daughters with four grandchildren and continued to live in Detroit. He was inducted into the Detroit High School Hall of Fame in 2017.55 Always with a thankful heart, when asked what one item he would definitely want in this biography, Ragland replied, “I just want to give a shoutout to all the people who stuck up for me.”56 No doubt, they would give a shoutout to Rags as well.

This article was published in “The Team That Couldn’t Hit: The 1972 Texas Rangers” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author was also helped by Baseball-reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Tom Ragland’s file from the Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame. Special thanks to Rod Nelson for research assistance.

Notes

1 Terry Pluto and Joe Tait, Joe Tait, It’s Been a Real Ball: Stories From a Hall-of-Fame Broadcasting Career. (Cleveland: Gray & Co., 2011), 83.

2 Russell Schneider, “Happiest Indian: ‘Daddy Rags,’” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 6, 1973: 34.

3 Author interview with Tom Ragland, April 26, 2017.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.; msuspartans.com/sports/c-track/spec-rel/081115aaa.html; msuspartans.com/genrel/093010aau.html.

7 Author interview.

8 Ibid.

9 “Know the Nats: Tommy Ragland,” Burlington (North Carolina) Times-News, April 27, 1967: 2B.

10 Author interview.

11 “Infield Could Be Key to Senators 1966 Hopes,” Geneva (New York) Times, April 23, 1966: 14.

12 Norm Jollow, “Wild Pitch in 10th Scuttles Senators, 3-2,” Geneva Times, July 16, 1966: 9.

13 “Popular Fellow,” Geneva Times, August 31, 1966: 3.

14 Author interview.

15 Ibid.

16 “Tom Ragland Arrives to Plug Hole at 2nd,” Geneva Times, July 26, 1967: 14.

17 “Mezich ‘Heps Out’ to Sink Senators Twice,” Geneva Times, July 27, 1967: 27.

18 “Highlightin’,” Burlington (North Carolina) Times-News, April 11, 1968: 12.

19 Joe Alli, “Ragland ‘Loose’ After First Hit,” Buffalo Courier-Express, April 28, 1969: 18.

20 Author interview.

21 Joe Alli, “Ragland Leads Herd Over Tidewater, 3-1,” Buffalo Courier-Express, March 27, 1969: 35.

22 Ibid.

23 “Ragland ‘Loose.’”

24 Ibid.

25 “Bisons Snap Wings’ Streak at Five, 7-3,” Buffalo Courier-Express, June 17, 1969: 21.

26 Joe Alli, “Herd Has Hopes for Star Berths,” Buffalo Courier-Express, July 21, 1969: 20.

27 Joe Alli, “Bisons Jeff Terpko Halts Columbus, 7-1,” Buffalo Courier-Express, May 9, 1969: 22.

28 “Denver Bears Top Wichita, Romp to Fifth Straight Win,” Greeley (Colorado) Daily Tribune, May 26, 1970: 25.

29 “Bears Down Omaha, 8-3, in Fourth Playoff Game,” Greeley Daily Tribune, September 9, 1970: 26.

30 John Woestendiek, “Last Men Out – Thirty-Four Years Later, Baseball and the Final Senators Game Still Resonate in the Lives of the Men in Washington’s Last Lineup,” Baltimore Sun, April 3, 2005: 1F.

31 Ibid.

32 “Washington Takes Wert Off List,” Abilene Reporter-News, April 21, 1971: 22.

33 “Ragland Homer Pushes Denver Past Omaha,” Greeley Daily Tribune, May 28, 1971: 28.

34 “Pitcher Gets Winning Run for Denver,” Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph, July 26, 1971: 14.

35 “Bears Win Title – in Junior World Series,” Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph, September 10, 1971: 14.

36 Eduardo Moncada, “Missing Stroke? Brant Finds It in Venezuela,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1971: 55. Eduardo Moncada, “Carew: Interim Pilot, Top Venezuelan Hitter,” The Sporting News, November 27, 1971: 55.

37 Author interview.

38 Russell Schneider, “Indians Tap Their Toes to Rags Time,” The Sporting News, June 9, 1973:19.

39 Russell Schneider, “Happiest Indian: ‘Daddy Rags,’” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 6, 1973: 34.

40 Ibid.

41 Author interview.

42 Russell Schneider, “Schneider Around,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 27, 1973: 50.

43 Ibid.

44 Author interview.

45 Russell Schneider, “Schneider Around,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 2, 1973: 34; June 6, 1973: 76.

46 Chuck Hickman, “Utilityman Suffers on Bench,” Daily Iowan (University of Iowa), August 28, 1973: 7.

47 Russell Schneider, “Schneider Around,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 30, 1974: 52.

48 Woestendiek.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid.

52 Author interview.

53 Jason Carmel Davis, “Former Major Leaguers to School Youngsters in Baseball Clinic,” C&G Newspapers (Warren, Michigan). Retrieved April 5, 2017. candgnews.com/sports/former-tigers-school-youngsters-baseball-clinic.

54 Author interview.

55 Author interview.

56 Ibid.

Full Name

Thomas Ragland

Born

June 16, 1946 at Talladega, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.