Frank Howard

He was not the first man to be recognized as a threat to break Babe Ruth’s record of 60 home runs in a season, but Frank Howard was surely one of the first to draw such attention while still in the minor leagues, or even in college. This gentle, humble man would be no match for Ruth in personality nor, it would turn out, in ability. Howard got a relatively late start on his professional career, and took several additional years struggling to reach the heights baseball observers had predicted for him. But in the end, he became an All-Star, a home run champion, a World Series hero, and one of the game’s most feared, and most admired, sluggers.

He was not the first man to be recognized as a threat to break Babe Ruth’s record of 60 home runs in a season, but Frank Howard was surely one of the first to draw such attention while still in the minor leagues, or even in college. This gentle, humble man would be no match for Ruth in personality nor, it would turn out, in ability. Howard got a relatively late start on his professional career, and took several additional years struggling to reach the heights baseball observers had predicted for him. But in the end, he became an All-Star, a home run champion, a World Series hero, and one of the game’s most feared, and most admired, sluggers.

Frank Oliver Howard was born on August 8, 1936, in Columbus, Ohio, to John and Erma Howard. John was a large man (6-foot-4, over 200 pounds) and a machinist for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in Columbus, while Erma was a homemaker. Frank was the third of six children who lived with their parents in a modest frame house. “There was always lots of food on the table,” Howard remembered, “but if we kids wanted money, we had to earn it.” Frank shined shoes, caddied, and did the hard manual labor befitting his size. “When I was 14,” he recalled, “I worked a hundred-pound jackhammer in the streets for the city of Columbus, got paid maybe a dollar and a half an hour and was glad to get it.”1 By the middle of his tenure at Columbus South High School, he had grown to 6-foot-5, 195 pounds.

John Howard had played semipro baseball around Columbus, and encouraged his son’s interest in the game. Despite his size, Frank had no interest in football, but he played both basketball (at which he excelled) and baseball (which he preferred). Howard was good enough to be widely recruited to play college basketball, but he decided to stay at home and play at Ohio State. “Frank was anxious to get an education,” recalled Floyd Stahl, his basketball coach at OSU, “but he had almost no money. We didn’t have the grants-in-aid and the sports scholarships that we have today. I told Frank I thought we could find jobs for him.” Howard did get some assistance from the school, but also worked around campus for four years. When Stahl got him a job working on a cement crew, the foreman told him, “Frank does twice as much work as any laborer I’ve had.”2 Stahl was soon concerned that Howard would work too hard and overtrain. Howard became a basketball star for the Buckeyes, earning All-American honors as a junior, and setting a Madison Square Garden record in a holiday tournament with 32 rebounds in a game, and 75 for the three games.3 The next year Howard was drafted by the Philadelphia Warriors of the NBA.

He also played baseball for Ohio State, eclipsing the .300 mark in two seasons and displaying occasional glimpses of the power for which he would become known. The Brooklyn Dodgers first scouted him in 1956, and the next year, when Howard was a junior, Cliff Alexander filed a telling report: “Good arm. Fielding below average. Hitting below average (good potential). Running speed slightly below average. Major league power. Definite follow.” What Alexander saw was an unfinished product, with a lot of potential. Howard played that summer of 1957 for Rapid City in the Basin League, a circuit that drew a lot of attention from big-league scouts. He almost signed that summer, but had promised Stahl he would return to Columbus for his final year of basketball.4

After his basketball season ended, he let major-league scouts know that he was ready to sign. He had a lot of offers, but the Dodgers (now in Los Angeles) had been talking to him for a couple of years and he never seriously considered anyone else. Alexander remembers Howard calling him up to tell him that Paul Richards, who was running the Baltimore Orioles at the time, had offered a $120,000 bonus. Howard asked Alexander for $108,000—$100,000 for himself, and $8,000 to be put toward a new house for his parents. Alexander agreed, and Howard was on his way.5 He left Ohio State one semester short of a degree in physical education.

The Dodgers sent their big recruit to their Green Bay team in the Class-B Three-I League, where he played for former Brooklyn star outfielder Pete Reiser. This first stop proved no difficulty at all, as Howard hit .333 and led the league with 37 home runs and 119 RBIs. At the end of the year he was named the league’s Most Valuable Player. One evening at a local pizza parlor he met Carol Johanski, a secretary for the Green Bay Gazette. Six months later they married, and Howard soon bought a house in Green Bay and settled there.

In September the 22-year-old was brought up to Los Angeles to finish the season. He made his debut on September 10, 1958, at Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium. Batting against Robin Roberts, he finished 2-for-4, including a mammoth two-run home run in his second big-league at-bat. The drive hit a billboard atop the left-field roof, causing left-fielder Harry Anderson to say he was afraid the billboard was going to fall over onto his head.6 On the 16th, he came to bat in Cincinnati with teammate Duke Snider on third base. Up in the radio booth, Dodgers announcer Vin Scully commented wryly that Snider was standing way off the foul line in deference to Howard’s propensity for pulling line drives down the line. Just as Scully said this, Howard hit a vicious foul liner that hit Snider in the head, knocking him briefly unconscious and ending the Duke’s season.7 Howard finished his brief trial hitting .241 in 29 at-bats.

In 1959 the Dodgers sent Howard to Victoria of the Texas League, which also proved to be no challenge. Through 63 games he looked to be on his way to a Triple Crown, with 27 home runs, 79 RBIs, and a .371 average. Dodgers GM Buzzie Bavasi paid the club a visit, watched Howard hit a 520-foot homer to win a game, and brought him back to Los Angeles. Howard only stayed a week, going just 2-for-19 before getting sent to Spokane (Triple-A Pacific Coast League). He hit .317 with 16 more home runs with Spokane in the second half, then returned to the Dodgers in mid-September. The club was in the middle of a pennant race so Howard only got two at-bats, including a pinch-hit home run off the Cardinals’ Lindy McDaniel on the 23rd. The Dodgers ultimately won the pennant and the World Series. After the season The Sporting News named Howard their Minor League Player of the Year.

By the spring of 1960, with 50 big league at-bats to his credit, Howard’s size, strength, and power had already led to a fair bit of commentary. Tales of 500-foot minor-league home runs, and his line drives that threatened base runners and infielders, were told repeatedly. In a day when many major leaguers were not even six feet tall, and when the biggest stars in the National League—Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Frank Robinson—were no more than 180 pounds, Howard had reached 6-foot-8, and was a full 250 pounds. In later years he would occasionally be heavier. Jim Gilliam, Howard’s 5-foot-10 teammate, spoke for many when he said, “a man that big should hit fifty homers every year—and I mean every year.”8 He was still a work in progress in the outfield and first base (a fine arm but slow to get moving), and he swung at way too many bad pitches. As one scribe noted, “Huge Frank has little comprehension of his own mammoth strike zone and but slight control over his all-or-nothing uppercut swing. Until he develops a modicum of finesse, Los Angeles will string along with its present quota of mere mortals.”9

As ballyhooed as Howard was, he still faced the task of landing a spot on a world championship team. He did fairly well in spring training in 1960 (.278 with two home runs), but had a minor run-in with manager Walter Alston about his lack of playing time and ended up back in Spokane to start the year. In 26 games there he hit .371, and returned to the Dodgers in May, this time to stay. He soon became the regular right fielder and, despite a late-season slump, ended up hitting .268 with 23 home runs. After the season he was named the National League Rookie of the Year.

His 1961 season began slowly because of a chipped bone in his thumb. Alston had intended to move him to first base, but the injury and recovery kept Howard out of the lineup early, and he ended up mainly platooning in right field, starting just 72 times. He actually hit better than his rookie year — .296 with 15 home runs in just 267 at-bats, but grew increasingly frustrated when he could not stay in the lineup.

After the 1961 season the Dodgers lost both of their first basemen, Gil Hodges and Norm Larker, in the expansion draft, causing them to move Ron Fairly to first and open up more playing time for Howard. Although he still only started 123 games, he hit .296 with 31 home runs (seventh in the league) and 119 RBIs (fifth). He was still an undisciplined hitter, with 108 strikeouts and just 39 walks. The Dodgers were a great offensive team, finishing second in the league in runs while playing in the pitcher-friendly Dodger Stadium (in its first year), and won 102 games before falling to the Giants in a best-of-three playoff series to decide the pennant.

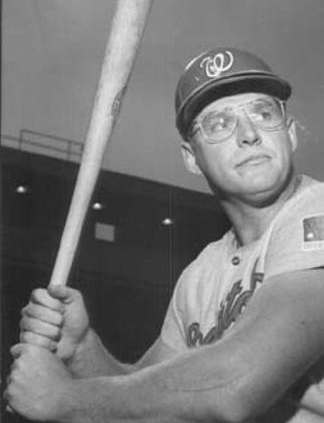

A big change for Howard came about in early 1963. “For years,” wrote Sports Illustrated, “he has tried to hit 90-mph pitches with 20/40 vision in his good eye and 20/60 in his left. He was second in the league in strikeouts last year, and his relations with fly balls were no better, particularly those appearing out of the L.A. smog. Last week Howard put on glasses and immediately whacked three home runs in four games.”10 Howard stayed hot for a while (.384 in April), but a bad slump (.167 in May, .194 in June) cost him his full-time job, as he alternated the rest of the season with Wally Moon in right field. He still managed 28 home runs (by far the most on the team) and a .273 batting average in 417 at-bats. Glasses or no, he set an all-time Dodgers record with 116 strikeouts at the plate. He wore glasses for the rest of his career.

Thanks mainly to their great pitching staff, the 1963 Dodgers returned to the World Series and swept the New York Yankees, who had won the Series the previous two seasons, in four straight game. Howard finished 3-for-10 in his three games, including two memorable shots. In the first game, facing Whitey Ford, he crushed a fastball 460 feet to deep left-center field for the “longest double in the 41-year history of Yankee Stadium,” reaching the fabled monuments that were on the playing field in that era. In the fourth game, in Dodger Stadium facing Ford again, he hit a slow curve 450 feet into the second deck in deep left field.11

After the 1963 season Howard was 27 years old and people no longer believed he would turn into Babe Ruth. In his four years he had been on the field about two-thirds of the time for the Dodgers, and had hit .282 and averaged 24 home runs per year. While others had called him the new Ruth, and then came down on him when he was less than that, Howard had a more measured view. “I think I am a realistic guy,” he said. “I have the God-given talents of strength and leverage. I realize that I can never be a great ballplayer because a great ballplayer must be able to do five things well: run, field, throw, hit and hit with power. I am mediocre in four of those — but I can hit with power. I have a chance to be a good ballplayer. I work on my fielding all the time, but in the last two years I feel that I have gotten worse as a fielder. My greatest fear was being on the bases, and I still worry about it. I’m afraid to get picked off. I’m afraid to make a mistake on the bases, and I have made them again and again, but here I feel myself getting better.”12 His throwing arm, once a strength, had been hurt when he shoved himself into a locker in a fit of anger.

Nonetheless, he wanted to know where he stood, and he went to see general manager Bavasi. “I didn’t go in and give it that old nonsense about play me or trade me, because the Dodgers have some mighty fine players,” said Howard. “I told Mr. Bavasi that these were my peak years as an athlete and that an athlete doesn’t get two or three sets of peak years. I wanted to play regularly, and Mr. Bavasi said I would get that chance this year. Manager Alston said it, too. Now it’s up to me.”13

Howard started the first 49 games of the 1964 season, but hit just .215 despite 14 home runs (second in the league to Willie Mays). At that point Alston began sitting Howard occasionally against right-handed pitchers, and he ended up with 433 at-bats, 24 home runs, and a .226 average. Alston and Bavasi had both come to believe that they could not win in Dodger Stadium with power; they needed pitching, defense, and speed. When Howard asked to be traded after the season, the Dodgers obliged. On December 4, they dealt Howard, third baseman Ken McMullen, and pitchers Phil Ortega and Pete Richert, to the Washington Senators for pitcher Claude Osteen, infielder John Kennedy, and $100,000. Without Howard, and ably abetted by Osteen in the starting rotation, the Dodgers went on to win the 1965 World Series without a single player who hit more than 12 home runs. “Disappointed in the trade? Oh, no,” recalled Howard. “I knew it was time. I was at the stage of my life where I had to find out if I could play every day.”14

The Washington Senators were an expansion team with four years under their belt — they had lost at least 100 games every year, and had reached no higher than ninth place. No matter. Howard was excited about going where he was wanted, and excited to play for Gil Hodges, his teammate from a few years earlier. Howard remained his own toughest critic, especially where his defense was concerned. “I’m not a complete player,” Howard admitted. “I can’t throw like a complete player should. And I don’t always hit the ball like I should. I do try, though.” Replied Gil Hodges: “Frank’s being paid to hit.”15 In 1965, Howard battled injuries all year, but played 149 games and hit .289 with 21 home runs and 84 RBIs, all team-leading figures. For the first time, he played mainly left field rather than right.

The Washington Senators were an expansion team with four years under their belt — they had lost at least 100 games every year, and had reached no higher than ninth place. No matter. Howard was excited about going where he was wanted, and excited to play for Gil Hodges, his teammate from a few years earlier. Howard remained his own toughest critic, especially where his defense was concerned. “I’m not a complete player,” Howard admitted. “I can’t throw like a complete player should. And I don’t always hit the ball like I should. I do try, though.” Replied Gil Hodges: “Frank’s being paid to hit.”15 In 1965, Howard battled injuries all year, but played 149 games and hit .289 with 21 home runs and 84 RBIs, all team-leading figures. For the first time, he played mainly left field rather than right.

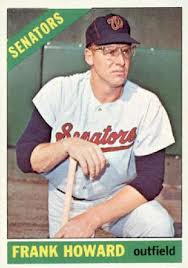

The next season his statistics were fairly similar (.278, 18, 71 in 146 games). In judging his record today, it is important to remember just how depressed run scoring was in the 1960s, especially in the American League. Although Howard was not a star, his OPS of .790 compared favorably to the AL’s .670. And he continued to make news, and add to his legend, with his long home runs — such as one he hit against the White Sox at D.C. Stadium in April. “Tommy John threw him something,” recalled teammate Fred Valentine, “and he hit a line drive back at him. John fell off the mound trying to get out of the way of the ball. [Center-fielder Tommie] Agee started in like he was going to catch a line drive. It was like a 2-iron, and it ended up in the upper deck in centerfield. They painted another seat.”16 (The Senators had begun painting seats in the upper deck to represent some of Howard’s long home runs.)

Before the 1967 season, Hodges worked with Howard to retool his swing. He felt that Frank’s level swing was producing hard ground balls, and asked Frank to try a slight uppercut and to stand closer to the plate so he could pull the ball more.17 The results were obvious, as Howard had 24 home runs by midseason in 1967, and ended with 36 (third in the league) and a .256 average. He led the league with 155 strikeouts, and walked only 60 times, but his OPS of .849 was still eighth in the AL. It was his best season to date.

In 1968 Hodges moved to New York to manage the Mets, and was replaced by Jim Lemon, a former outfielder for the old Washington Senators who had been an all-or-nothing slugger like Howard, hitting as many as 30 home runs and leading the AL in strikeouts three times. This year, 1968, is historically recognized as the Year of the Pitcher, as the AL hit .230 and had shutouts in 20 percent of its games. Bucking this trend, Howard took a step forward and became the hitter people had predicted he would become a decade earlier.

He hit .338 in April, but his best stretch came in early May when he collected 10 home runs and 17 RBIs in a span of six games. In so doing, he set records for home runs in four games (7), five games (8), and six games (10). Detroit pitcher Joe Sparma, who gave up the eighth home run in this streak, said, “He always was good for 30 home runs anyway, but this year he’s clobbering my best pitches. I think he’ll hit 70.” “No,” contradicted teammate Jim Northrup, “he’ll hit 75.”18 As late as June 9, Howard held league leads in home runs (22), runs batted in (47), and batting average (.342). As the AL had had Triple Crown winners in each of the last two seasons (Frank Robinson and Carl Yastrzemski), Howard’s statistics were getting quite a bit of attention. As usual, the slugger himself was less impressed than the media. “All I’m trying to do is get three good cuts each time up. I haven’t changed my swing, and I don’t kid myself — I’m a streak hitter and I’m hot.”19

For the season, Howard settled down to hit .274, which was still 10th in the AL. He led the league with 44 home runs, 330 total bases, and a .552 slugging percentage, huge numbers for 1968, and finished second with 106 RBIs. He started his first All-Star Game, playing right field and batting fourth, going 0-for-2 in the AL’s 1-0 loss in the Astrodome. In August he turned 32, and people were writing like he had finally figured out how to hit. For the first time in his career, he also played quite a bit of first base, starting 51 times there. “Jim Lemon did a marvelous job with me,” Howard recalled. “He just took it a little further than Gil took it in ’67. He moved me a little closer to the plate, spread me out a little bit more, cut down on the overstride, and as a result, I was starting to get a little more selective at the plate, and probably had my first really good year in the big leagues.”20

Howard had picked up the nickname “Hondo” early in his career, and it endured. Once he joined the Senators, and especially once he became a star, he picked up two more nicknames: the “Washington Monument” and “Capital Punisher.” The names played on his new environs along with his strength and formidable presence in the batter’s box, but both sobriquets belied his gentle nature. He was nice to everyone but pitchers.

After the Senators’ 10th-place finish, new owner Bob Short took over in January 1969 and decided to replace Lemon after his single season. To replace Lemon, Short lured Ted Williams out of his eight-year retirement, surprising everyone around the game. For Howard, this would be another turning point, perhaps the most important one. Williams believed he knew how to make Howard a better hitter. “He called me into his office one day in the spring of ’69,” Howard recalled. “He said, ‘Bush! Come on in here.’ I’d only been in camp a couple of days, and I’m thinking, ‘Gee, I’m not in his doghouse already, am I?’”

“Can you tell me how a guy who hit 44 home runs only got 48 walks?” asked Williams. After Howard offered some explanation, his manager got to the point. “Well, let me ask you. Can you take a strike? I’m talking about if it’s a tough fastball in a tough zone, first pitch. Or if it’s a breaking ball, you’re sitting on a fastball … Can you take a strike? You know, try to get yourself a little better count to hit in?” Howard said he could. “Well try it for me.”21

In the event, Howard increased his walk total from 54 to 102, while his strikeouts fell from 141 to 96. He took advantage of more hitter’s counts, and ended up hitting .296 with 48 home runs and 111 RBIs. He led the league with 330 total bases, and finished among the leaders in on-base-percentage (.402) and slugging percentage (.574). He hit a home run off Steve Carlton in the All-Star Game, held at his home park of RFK Stadium.

“I did it without even trying to walk,” said Howard. “I was ready to hit, if it was my pitch, but if it was something other than I was looking for, I took it. I was laying off some bad pitches, getting more counts in my favor, and all because of Ted Williams. He’s one in a million! A marvelous, marvelous, man!”22 One wonders what kind of career Howard might had if he had learned to do this 10 years earlier. People had been trying to get him to lay off bad pitches his entire career. Williams, with a very simple piece of advice, succeeded. Williams was impressed. “He still hit more home runs, some of them out of sight. I mean he crushed the ball. I think without question the biggest, strongest guy who ever played this game.”23 Williams had quite an influence on the rest of the team as well, as they finished in third place in the new six-team AL East with an 86-76 record. Williams was named the league’s Manager of the Year.

The next year the team fell back to 70 wins and last place (losing their final 14 of the year), though Howard kept hitting. Playing 161 games in left field and first base, he led the AL in home runs (44), RBIs (126), and walks (132). Twenty-nine of his walks were intentional, as pitchers had begun to realize that they could no longer get him to chase bad pitches with runners on base. Indians manager Al Dark walked him intentionally 12 times in 18 games. His star pitcher, Sam McDowell, was particularly afraid of Howard, who hit .368 with five home runs in 68 at-bats off McDowell in his career. It might have been worse; McDowell walked Howard 25 times, including nine times intentionally. Twice in 1970 Dark moved McDowell to another position with Howard due up, then moved him back to the mound when the coast was clear.

Although Howard had just had his three best seasons, he had turned 34 years old. He dropped back at bit in 1971, hitting .279 with 26 home runs, though his 83 walks helped him remain one of the league’s most valuable offensive forces. His dropoff might have been aided by showing up in camp weighing 297 pounds. He worked hard in the spring to remove the weight, though it might have weakened him to start the season. The big story in Washington that season was the protracted public effort to find a local buyer for the team, a story that resolved itself late in the season when Short received permission from the American League to move the Senators to Arlington, Texas. In the team’s last game, on September 30, 1971, Howard hit the final home run by a Washington Senator, though the game was ultimately forfeited to the Yankees when the angry fans stormed the field in the ninth inning. After Howard hit the home run, he received a standing ovation, and waved to the crowd from the dugout steps with tears in his eyes.24 Major-league baseball did not return to Washington for 34 years.

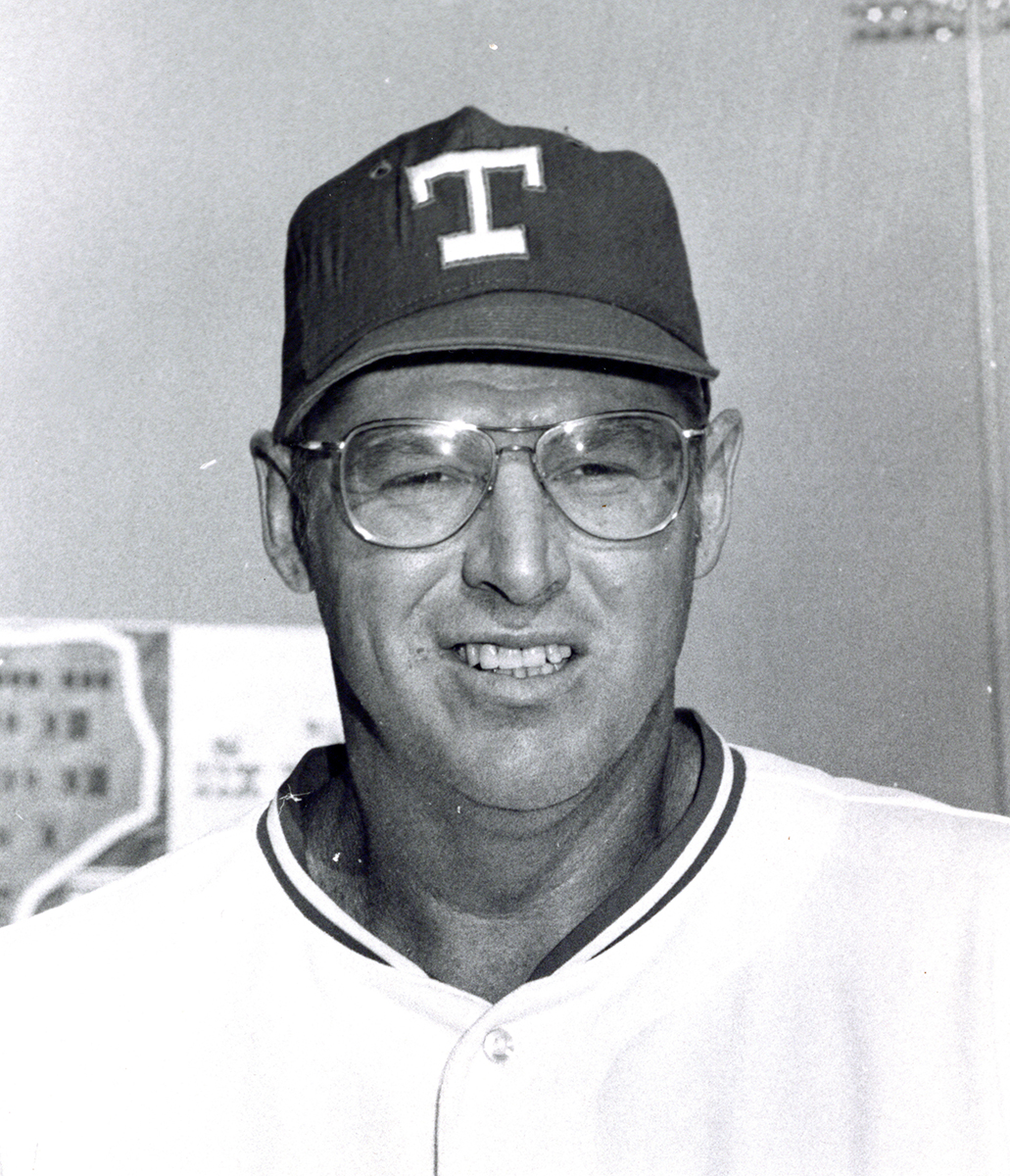

Howard had become one of the higher-paid players in the game, reaching $125,000 by 1970 and staying there for a few years. In early 1972, prior to reporting to the brand new Texas Rangers, he held out for a small raise but likely settled for maintaining his $120,000 salary. He still lived in Green Bay, where he owned several shopping centers, but at least one scribe thought he ought to head to camp: “Considering the prevailing temperatures in Green Bay this time of year, it’s a wonder Howard doesn’t settle just to get warm.”25 After he did so, and after a brief player strike that spring, on April 21, 1972, Howard appropriately hit a home run in his first home at-bat for the Rangers, the first hit in Arlington Stadium, a long drive to dead center. “A guy just does the best he can,” said Howard. “We’re aware you can’t peddle a poor product to the public. It’s nice to think that these people’s first memory of major league baseball might be my home run, but I really hope that their memory is the win.”26

Howard had become one of the higher-paid players in the game, reaching $125,000 by 1970 and staying there for a few years. In early 1972, prior to reporting to the brand new Texas Rangers, he held out for a small raise but likely settled for maintaining his $120,000 salary. He still lived in Green Bay, where he owned several shopping centers, but at least one scribe thought he ought to head to camp: “Considering the prevailing temperatures in Green Bay this time of year, it’s a wonder Howard doesn’t settle just to get warm.”25 After he did so, and after a brief player strike that spring, on April 21, 1972, Howard appropriately hit a home run in his first home at-bat for the Rangers, the first hit in Arlington Stadium, a long drive to dead center. “A guy just does the best he can,” said Howard. “We’re aware you can’t peddle a poor product to the public. It’s nice to think that these people’s first memory of major league baseball might be my home run, but I really hope that their memory is the win.”26

It was not a harbinger, as Howard’s days of stardom were behind him. He hit just .244 with nine home runs in 95 games before being sold to the Detroit Tigers on August 31. The Tigers were in a fight for the AL East title, and acquired Howard to platoon at first base with Norm Cash. Howard hit .242 for the month, but had one big day — a 3-for-4 performance against the Orioles on September 21 that included a home run off Dave McNally. As the Tigers won the division by a half-game, Howard’s contributions were important. Because he did not report to the Tigers until September 1, he was ineligible to play in the AL Championship Series against Oakland, which defeated Detroit in an agonizingly close five-game series.

The next season marked the advent of the designated hitter rule in the AL, a change tailor-made for the 36-year-old Howard — or the 26-year-old Howard, for that matter. He played 85 games for the Tigers, only three times in the field, and hit 12 home runs and batted .256. In October he drew his release, ending his major-league career. He signed for 1974 to play with the Taiheyo Lions of Japan’s Pacific League, but he hurt his back in his very first at-bat, and never played again. Howard’s playing career was over at age 37.

With his popularity, it is not surprising that Howard enjoyed an extensive post-playing career in the game. He managed the Spokane Indians in 1976, but returned to the major leagues as a coach with the Milwaukee Brewers the next and remained in the majors for most of the next 20 years. He had two brief trials as manager. He led the San Diego Padres in the strike-marred 1981 season, but was let go after the team finished last in both halves of the split season. Two years later he took over the New York Mets when George Bamberger was fired 46 games into the 1983 season, but Howard was not offered the job after the Mets finished last. Howard was well respected as a coach, but his employers seemed to feel that he was too nice a guy to be a successful manager. Besides the Brewers and the Mets, he also served as coach with the Seattle Mariners, the New York Yankees and the Tampa Bay Devil Rays.

After spending offseasons in Green Bay for many years, by the early 1990s Howard had resettled in Northern Virginia where his years of stardom in Washington made him a popular and revered figure. He and Carol raised six children, but their marriage later ended and in 1991 he remarried, and he and second wife Donna were still happily together in 2012. When the major leagues returned to Washington in 2005, with the relocation of the former Montreal Expos, Howard became the most visible link to the previous major-league teams that had played there. Especially in the Nationals years at RFK Stadium, Howard’s old park, fans got a visible reminder of the old star anytime they looked at the painted seats, still visible in the upper deck. In 2008 the Nationals began play in the brand-new Nationals Park, and the next year unveiled three statues in their center field plaza, depicting Walter Johnson (who pitched for the first 20th-century version of the Washington Senators), Josh Gibson (who starred in the Negro Leagues for the Homestead Grays, who played in Griffith Stadium), and Howard (representing the expansion Senators). When the Nationals reached the postseason in 2012, Howard threw out the ceremonial pitch of the Division Series before Game Four.

The Nationals announced news of his death at the age of 87 on October 30, 2023.

Long after he had retired, Howard was often called upon to look at back on his career, especially the years prior to his stardom, and he always did so objectively. “To be totally honest, had I made some adjustments — hitting-wise — earlier in my career, instead of just going up there [swinging at everything], I would have had better years. When people look back on their careers, they say they wouldn’t change a thing. I would have. I would have made the adjustments. I would have given myself the chance to put up big numbers.”27

But let us not dwell on what Frank Howard did not accomplish, and instead marvel at what he did: 382 home runs, two home run titles, an RBI title, a World Series home run and championship, three All-Star Games, and the admiration of most of greater Washington, D.C. The man has a statue outside of a big-league ballpark, an honor not bestowed on many players. For a few years there, a big-league pitcher would rather face just about anyone in the world instead of Frank Oliver Howard, the Capital Punisher.

Photo credits

Frank Howard with Washington Senators: Trading Card Database.

Frank Howard with Texas Rangers: SABR-Rucker Archive.

Notes

1 John Devaney, “Frank Howard: Goliath Grows Up,” Sport, September 1968: 65.

2 William Leggett, “The Dodgers’ Troubled Giant,” Sports Illustrated, May 25, 1964.

3 Al Hirshberg, Frank Howard—The Gentle Giant (New York: Putnam, 1973), 22.

4 Ed Linn, “Frank Howard—The Man Behind the Babe Ruth Myth,” Sport, April 1961: 61. The Cliff Alexander report is included in this article.

5 Mike Bryan, “Reflections on the Game,” Sports Illustrated, May 25, 1989.

6 Ed Linn, “Frank Howard,” 67.

7 John Schulian, “The Boys Of Summer Were The Boys Of Slumber The First Year In Los Angeles,” Sports Illustrated, April 14, 1975.

8 Allan Roth, “Frank Howard’s Baseball Diary,” Sport, July 1960: 21.

9 “Los Angeles DODGERS,” Sports Illustrated, April 11, 1960.

10 “Baseball’s Week,” Sports Illustrated, May 6, 1963.

11 William Leggett, “Koo-foo the Killer,” Sports Illustrated, October 14, 1963.

12 William Leggett, “The Dodgers’ Troubled Giant,” Sports Illustrated, May 25, 1964.

13 Ibid.

14 James R. Hartley, Washington Senators (Washington, D.C.: Corduroy Press, 1998), 45.

15 Mark Mulvoy, “Baseball’s Week,” Sports Illustrated, June 14, 1965.

16 James R. Hartley, Washington Senators, 54.

17 “Rising Dynasty for the Birds,” Sports Illustrated, April 17, 1967.

18 Peter Carry, “Highlight,” Sports Illustrated, May 27, 1968.

19 Ibid.

20 James R. Hartley, Washington Senators, 91.

21 James R. Hartley, Washington Senators, 94.

22 James R. Hartley, Washington Senators, 105.

23 John Underwood, “Ted Williams—My Year,” Sports Illustrated, January 26, 1970.

24 Don Oldenburg, “No Place Like Home,” Washington Post, March 22, 2005: C1.

25 “People,” Sports Illustrated, March 6, 1972.

26 Harold Peterson, “New Home on the Range,” Sports Illustrated, May 1, 1972.

27 Bill Ladson, “Q&A with Frank Howard—Former Senators Slugger discusses career in Washington,” Washington Nationals Website (http://washington.nationals.mlb.com), January 22, 2009.

Full Name

Frank Oliver Howard

Born

August 8, 1936 at Columbus, OH (USA)

Died

October 30, 2023 at Aldie, VA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.