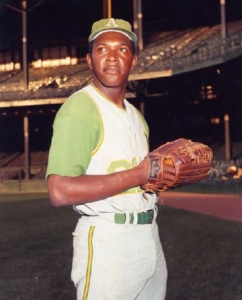

Vida Blue

Vida Blue burst onto the scene in major-league baseball as a fire-balling left-hander for the Oakland A’s and served as one of the primary characters in the A’s streak of five division championships and three World Series championships. His career, which spanned from 1969 to 1986, would see high points, including the multiple World Series championships and outstanding pitching performances, as well as dark days, such as his suspension from the game for drug use and his involvement in one of the most publicized contract holdouts in the history of the game. In many ways, the ups and downs of Blue’s baseball career, both on and off of the field, reflected the times during which he played perhaps more than any other of his contemporaries.

Vida Blue burst onto the scene in major-league baseball as a fire-balling left-hander for the Oakland A’s and served as one of the primary characters in the A’s streak of five division championships and three World Series championships. His career, which spanned from 1969 to 1986, would see high points, including the multiple World Series championships and outstanding pitching performances, as well as dark days, such as his suspension from the game for drug use and his involvement in one of the most publicized contract holdouts in the history of the game. In many ways, the ups and downs of Blue’s baseball career, both on and off of the field, reflected the times during which he played perhaps more than any other of his contemporaries.

Vida Rochelle Blue, Jr. was born on July 28, 1949, in Mansfield, Louisiana, a small town in the northern part of the state. He was the eldest of six children born to Vida Blue Sr. and Sallie Blue. His father was a laborer, and Blue remembered having everything he needed, although not everything that he wanted, as he grew up.1 He recalled Mansfield as a town that was still segregated, with a white high school and a black high school, DeSoto High, which Blue attended. As a youngster Blue played baseball and football with his peers. He was a good athlete, and could throw a baseball very hard when he was still quite young.

When he entered high school, the school did not have a baseball team. However, the principal recognized Blue’s talent and formed a school baseball team around him.2 Blue’s pitching prowess got the attention of scouts, including Kansas City A’s scout Ray Swallow. Despite Blue’s wildness – he once pitched a no-hitter and struck out 21 in a seven-inning game, but lost the game due to ten walks – his skill was evident. Blue was equally renowned as a high-school football player, starring as a quarterback. He was recruited by major colleges, including Notre Dame, Purdue, and Houston. Houston was recruiting Blue to play quarterback at a time when there were no African-Americans playing quarterback for major colleges. But Blue’s father died during his senior year in high school, and he decided that he needed to support his family. Baseball would provide that support sooner than football might. He was selected by the Kansas City Athletics in the second round of the 1967 draft and was offered a two-year contract a $12,500 per year. Although he later said he had a stronger desire to play football than baseball, Blue signed with the A’s.

Blue’s professional baseball career began in the Arizona winter instructional league in 1967. He pitched in nine games, striking out 26 batters while walking 22 in 34 innings. At age 18, he reported to spring training with the A’s for the 1968 season, then was assigned to the Burlington Bees of the Class A Midwest League. Blue started the season opener against the Quad City Angels and struck out 17 while giving up only three hits in eight innings. On June 19, in the first game of a doubleheader, Blue pitched a no-hitter in the seven-inning game. Throughout the season, Blue developed his curveball to go along with his dominant fastball, and improved his control. He finished with a record of 8-11 in 24 games, pitching 152 innings and striking out 231 while walking 80.3

For the 1969 season, Blue was assigned to Double-A Birmingham. He pitched in 15 Southern League games, going 10-3, with 112 strikeouts and 52 walks in 104 innings. Oakland A’s owner Charlie Finley was anxious to bring Blue up to the majors, seeing him as his next pitching star. Blue was called up in July, and made his major-league debut on July 20, starting against the California Angels. He lost the game, pitching into the sixth inning and giving up home runs to Aurelio Rodríguez and Jim Spencer. He started three more games, including a win on July 29 over the New York Yankees, before being sent to the bullpen for the rest of the season. In his first major-league season, he finished with a record of 1-1, pitched 42 innings, struck out 24 while walking 18, and finished with an earned-run average of 6.64. Joe DiMaggio, then a coach with the A’s, said of Blue, “It was a shame to bring up a kid like that when he hasn’t pitched two pro years. He throws as hard as anybody, but he hasn’t learned to pitch yet.”4

Blue was sent to the Triple-A Iowa Oaks (American Association) to start the 1970 season. There he crossed paths with fellow pitcher Juan Pizarro. Blue learned a great deal from the veteran Pizarro, and later said that “[Pizarro] helped me more than any single person in my career.”5 With Pizarro’s help, Blue made adjustments in his delivery that helped him to achieve greatness. He was rested for a few weeks in the middle of the season because of an injury, but came back to finish the season. In 17 games, Blue put together a record of 12-3 while striking out 165 in 133 innings.

He was called up to the A’s in September, and started the first game of a Labor Day doubleheader against the White Sox in Chicago’s Comiskey Park. Although he helped himself by hitting a three-run home run, he was knocked out of the game after giving up four runs in less than five innings. However, in his next outing he pitched a complete-game one-hitter against the Kansas City Royals, giving up a single to Pat Kelly with two outs in the eighth inning. After a lackluster start against the Milwaukee Brewers, Blue faced the division-leading Minnesota Twins on September 21. He was matched against Jim Perry, who would win 23 games and the Cy Young Award that season. Blue was the star that night, however, throwing a no-hitter and walking only one batter. Finley telephoned the locker room after the game to congratulate his new star pitcher and tell him he would receive a $2,000 bonus for the performance. Blue made two more starts that season and finished the season as one of the young star pitchers in baseball. Along with Catfish Hunter, Blue Moon Odom, and Rollie Fingers, the A’s pitching staff was one of the primary reasons the A’s would have high expectations for the next few seasons.

Although Blue made a spectacular splash in 1970, his 1971 season ranked among the great pitching seasons of all time. The A’s made the franchise’s first postseason appearance since 1931. It may have been their best season of the 1970s despite the fact that they won the World Series in the following three seasons, 1972-1974.

Blue pitched the 1971 season opener for the A’s in Washington against the Senators, and took the loss, pitching only into the second inning. He then won ten straight games, including nine complete games, and over the course of the season received the attention of the nation. He appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated and Time. As a hard-throwing left-hander, the press compared Blue favorably to Sandy Koufax. However, this comparison was clearly difficult for Blue as Koufax was one of the greatest pitchers ever, and his prowess was nearly impossible to match. Veteran player Tommy Davis was one of Blue’s best friends and a roommate that season. Davis helped him to navigate through the heavy load of press requests, as well other demands for his time. Anything Blue did drew the attention of the press. For example, it became known that he carried two dimes in his pocket when he pitched. Although it was likely a charm Blue used in his pursuit of winning 20 games, he would not verify that to the press, which drew even more attention.

Blue’s start on July 9 against the California Angels was perhaps his best performance of the season. Although he did not get a decision in the game (he was going for his 18th win), he went 11 innings, gave up seven hits, no walks, and no runs while striking out 17 batters. The A’s eventually won the game 1-0 in 20 innings. In his next appearance, Blue started the All-Star Game for the American League. Although he gave up home runs to Henry Aaron and Johnny Bench, he was the winning pitcher, the youngest in All-Star Game history. Blue’s performance declined slightly in the second half of the season. He won his 20th game on August 7, and won his next two starts, raising the question of whether he could win 30 games for the season. But after number 22, he won only two and lost four of his last nine starts of the season. Surely he tired as the season wore on. The previous season, between the minors and majors, Blue pitched only 171 innings. In 1971, he pitched 312 innings. He finished the season with a record of 24-8 and a league-leading ERA of 1.82, and allowed the fewest runners per inning in the American League.

In the American League Championship Series, Blue faced off against the defending champion Baltimore Orioles and pitcher Dave McNally in Game One in Baltimore. The Orioles matched the A’s in wins, with 101, and the opening game would be a test of Blue. He had a 3-0 lead going into the bottom of the fourth inning, but gave up a run in that inning, and four more in the eighth to lose the game. The A’s were swept in three games, bringing an anticlimactic close to Blue’s magical season.

Despite his dominant regular-season performance, Blue had competition for the American League Cy Young Award. Detroit’s Mickey Lolich had surpassed Blue in wins with 25 to Blue’s 24, and in strikeouts, 308 to 301 (although Lolich pitched a staggering 376 innings). However, Blue edged out Lolich to win the Cy Young Award. Blue actually had an easier time winning the American League Most Valuable Player Award, finishing well ahead of teammate Sal Bando in the voting.

In 1971 Blue became involved in his first controversy with owner Charlie Finley. Finley offered Blue $2,000 to change his middle name legally to “True.” The always creative Finley saw the nickname as another way to market his pitching superstar. Blue declined the offer. He liked his name, thought it unique as it was, and had no desire to change it. Finley however would not let the idea rest. When Blue pitched, his name appeared on the scoreboard as “True Blue.” Finley instructed the A’s radio and television announcers to refer to Blue by the nickname. Blue asked them to stop, and also asked the team’s public-relations people not to refer to him as True Blue in press releases or to use the name on the scoreboard. This situation began the friction between Blue and Finley that blew up after the end of the season.

After his spectacular 1971 season, Blue demanded a pay raise. In 1971 he had made $14,750 in salary and $6,365.58 as his share of the postseason money, and also got a Cadillac as a bonus from Finley. Finley offered a raise, but not nearly what Blue wanted. Bob Gerst, an attorney representing Blue, presented an opening offer to Finley of $115,000. Later he told Finley that Blue would accept $85,000, which was a little less than the average salary paid to the top ten highest paid pitchers in baseball. Finley said he would pay Blue no more than $50,000.

Finley held firm, making the negotiations public and declaring that Blue would not be seeking so much if he had not hired a lawyer to represent him. Both sides made their case to the press and the public, and the acrimonious situation became referred to as “The Holdout.” The situation also served to elevate scrutiny of the reserve clause, which was under new attack by the players. Marvin Miller, director of the Players Association, was critical of Finley and the reserve system.

The holdout extended into spring training. On March 16 Blue and Gerst held a televised press conference to announce that Blue was withdrawing from baseball to take a position with the Dura Steel Products Company. While Blue actually did work for the company for a time, this was obviously an effort to combat Finley as it was clearly Blue’s desire to play baseball.

When the season started, Blue was placed on the restricted list, meaning he could not play for the first 30 days of the season. The major-league season was delayed ten days by a players strike in spring training, and opened on April 15 without Vida Blue. In late April Commissioner Bowie Kuhn organized a meeting between Finley, Blue, and Gerst. They reached an agreement on a $63,000 deal. However, Finley and Blue couldn’t agree on the wording of the announcement of the agreement. Finley did not want to appear as conceding anything, and insisted that he was paying Blue $50,000, an additional $5,000 signing bonus, plus $8,000 for Blue’s college fund. Blue wanted the deal to state what it was: payment of $63,000. Finally, on May 2, Blue signed for the package.6

Although Blue had missed only 18 playing days, he had not been conditioning and practicing as he would have during spring training and was not ready to pitch. He did not make his first appearance, which was only one inning long, until May 24. The 1972 season was tough for Blue. Although he did post a relatively good ERA of 2.80 and allowed only 165 baserunners in 151 innings, he finished with a disappointing record of 6-10.

His team, of course, won the American League West and faced the Detroit Tigers in the League Championship Series. Blue pitched exclusively out of the bullpen, pitching middle relief in Games One, Three, and Four. In each appearance, the games were in the balance, and Blue acquitted himself well. In the fifth and decisive game, Blue relieved Blue Moon Odom in the sixth inning of a 2-1 game, and pitched the final four innings for the save.

In the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds, Blue pitched in relief in Game One, picking up the save, as well as in Games Three and Four. With the A’s leading three games to two, he started Game Six. He was not as sharp as a starter as he had been in relief, and allowed three runs, including a Johnny Bench home run, in 5⅔ innings, and took the loss. The A’s won Game Seven, 3-2.

In 1973 Blue returned to form as an All-Star-caliber pitcher. He went 20-9, with an ERA of 3.28. While he was not the power pitcher that he was in 1971, striking out 158 in 263⅔ innings, he was described by many as a smarter pitcher. A Sports Illustrated article quoted teammate Sal Bando as saying, “In the first part of 1971 Vida was overpowering everybody, now he is overmatching them.”7 The article described Blue’s pitching style: “He jogs out to his position and works with quick efficiency, throwing his left-handed darts out of a fluid, high-kicking motion.” Blue’s pitching repertoire included his highly regarded fastball as well as a good curveball and changeup.

For the first four months of the 1973 season, Blue pitched well, but was often inconsistent. He hit his stride in August, winning six straight starts, including four complete games. He put together another streak of five consecutive wins in September, helping to lead the A’s to a division win over the Kansas City Royals. In the American League Championship Series, Blue started Game One against the Baltimore Orioles’ ace, Jim Palmer. Blue did not make it out of the first inning, giving up three hits and two walks before being relieved by Horacio Piña. Baltimore got four runs in the inning, and won, 6-0.

Blue again faced Palmer in Game Four and pitched much better. Through six innings he shut out the Orioles, giving up only two hits as the A’s held a 4-0 lead. However, after getting one out in the seventh, Blue gave up a walk to Earl Williams, a single to Don Baylor, an RBI single to Brooks Robinson, and a three-run home run to Andy Etchebarren, tying the game, 4-4. He was relieved by Rollie Fingers, who went on to lose the game, 5-4.

In the World Series against the New York Mets, Blue’s postseason troubles continued. He started Games Two and Five, both against Jerry Koosman. In Game Two, a high-scoring affair, Blue gave up solo home runs to Cleon Jones and Wayne Garrett. He was relieved in the sixth inning after allowing two baserunners who would later score. The Mets went on to win the game 10-7 in 12 innings. In Game Five, Blue gave up two runs in 5⅔ innings and lost to Koosman who, with reliever Tug McGraw, shut out the A’s, 2-0. The A’s won the Series, softening the effects of Blue’s lackluster pitching.

In 1974, although his won-lost record was not as impressive as in 1973, Blue pitched equally well. He finished with a record of 17-15 and an ERA of 3.25. He was durable, making 40 starts, and struck out 174 batters in 282⅓ innings. The A’s faced off again against the Orioles in the AL Championship Series. With the series tied one game apiece, Blue started Game Three, matched up again against Jim Palmer. Unlike 1973, Blue pitched brilliantly. He pitched two-hit, no-walk shutout, striking out seven in the 1-0 win. In the World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers, Blue started Games Two and Five, matched up against Don Sutton in both games. In Game Two he was bested by the Dodgers, giving up a run in the second and a two-run homer to Joe Ferguson in the sixth, taking the 3-2 loss. In Game Five Blue pitched five shutout innings before giving up two tying runs in the sixth. After allowing a walk in the seventh, Blue was relieved by Blue Moon Odom, who went on to win the game for the A’s.

The 1975 season was Vida Blue’s best since his masterful 1971 season. He started the All-Star Game and finished the season with a record of 22-11 and an ERA of 3.01. With the departure of Catfish Hunter to the Yankees, Blue and Ken Holtzman starred on the A’s pitching staff and helped to lead the A’s to their best record since 1971. Among his pitching highlights that season, Blue was the starter and one of four A’s pitchers to pitch a combined no-hitter against the California Angels on September 28, in the last game of the season. However, after three straight World Series championships, the A’s were swept in the AL Championship Series by the Boston Red Sox. Blue started Game Two against Reggie Cleveland. He gave up a two-run home run in the fourth inning to Carl Yastrzemski and two more hits before being relieved. Although he had ten more seasons in the major leagues, this was Blue’s last postseason appearance. Over his career, his postseason numbers were unexceptional, with a record of 1-5 and an ERA of 4.31 in 17 appearances.

The 1976 season was another controversial year in Blue’s career, although the controversy was not of his doing. Starting with the departure of Catfish Hunter to the Yankees before the 1975 season and the trade of Reggie Jackson and Ken Holtzman to the Orioles before the 1976 season, the dynastic A’s were being dismantled. Through mid-June, the A’s were in fifth place in the West Division, 11 games behind the Royals. Blue had a record of 6-6 in 15 starts, with an ERA of 3.09. Then, just a few hours before the June 15 trade deadline, Charlie Finley announced that he was selling Blue to the New York Yankees for $1.5 million, and Joe Rudi and Rollie Fingers to the Red Sox for $2 million. However, the transactions were held up by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn. Kuhn and Finley had battled over a number of issues over the years, but this event brought their rancorous relationship to a breaking point. In retrospect, the attempted sale of these players was yet another step in the process of transitioning from the rule of the reserve system and moving toward free agency for players. It foreshadowed transactions in the years to come. Kuhn justified his concern with the transactions, stating: “The issue is whether the assignment of the contracts is appropriate or not under the circumstances. That’s the issue I have to wrestle with. I have to consider these transactions in the best interest of baseball.”8

On the 18th Kuhn announced that the sale of the three players would not be in the best interests of baseball, and disallowed them. Blue thus remained with the A’s. However, with all of the legal threats made by Finley after Kuhn’s ruling, Blue did not pitch again until July 2. Both he and the A’s improved over the remainder of the season. Blue finished 1976 with a record of 18-13 and an ERA of 2.35, and the A’s finished in second place, 2½ games behind the Royals.

In 1977 the team was truly dismantled, not by Finley’s actions, but by his inaction in signing his players who were now eligible for free agency. Joe Rudi, Rollie Fingers, and Sal Bando, who had all been with the team throughout the championship years, left the A’s via free agency. However, Blue had signed a three-year contract before the “trade” to the Yankees, and was ineligible for free agency. The 1977 season was a forgettable one for Blue. He led the league in losses with a record of 14-19, and had an ERA of 3.83. The A’s finished last in the American League West, behind even the expansion Seattle Mariners.

During 1978 spring training, Blue was traded to the San Francisco Giants, giving him a new opportunity. For Blue the A’s got seven players and $300,000. The new environment with the Giants and distance from Charlie Finley helped to restore his career as he became the ace of the Giants’ pitching staff. The Giants were a solid squad, and were in first place as late as August 15 before fading and finishing in third for the 1978 season. Blue started the All-Star Game for the National League, making him the first pitcher to start the game for both leagues. He had a very good year overall, going 18-10 with a 2.79 ERA. He finished third in the balloting for the NL Cy Young Award and was named The Sporting News National League Pitcher of the Year. Although he was only 28 years old and his career would extend on for several years, 1978 was Blue’s last great year. In 1979 he and the Giants saw a significant decline. Blue finished the season with a record of 14-14 and an ERA of 5.01 while the Giants finished 19½ games under .500 and in fourth place. In 1980 Blue rebounded a bit, with a record of 14-10 and an ERA of 2.97. In the strike-shortened 1981 season, he went 8-6 with a 2.45 ERA. It was the first full season in Blue’s career in which he did not win 14 or more games. He did pitch and get the win in the All-Star Game, becoming the only pitcher to win the game for each league.

On March 30, 1982, at the end of spring training, Blue was traded with another player to the Kansas City Royals for four players. He pitched pretty well for the Royals, with a record of 13-12 an ERA of 3.78, and led the pitching staff in strikeouts. He did fade at the end of the season. After throwing a one-hitter against the Mariners on September 13, Blue started four more games, losing his last three decisions while his ERA grew from 3.36 to 3.78. In 1983 Blue struggled mightily. After seven starts and a record of 0-3 he was relegated to the bullpen. He stayed in the pen and made spot starts, but did not pitch well in either role. With a record of 0-5 and an ERA of 6.01, he was released by the Royals on August 5.

At the time, Blue’s problems on the field paled in comparison with his problems off the field. Blue and Royals teammates Willie Wilson, Jerry Martin, and Willie Mays Aikens were implicated in buying cocaine. Blue pleaded guilty to cocaine possession and served 81 days in prison. On December 15, 1983, he was suspended for a year by Commissioner Kuhn. He was out for the 1984 season, then after being reinstated he signed with the Giants in the spring of 1985. Considering that he had missed a full season, Blue pitched respectably as both a starter and reliever, going 8-8 with a 4.47 ERA in 1985. In 1986, he returned to the Giants, pitching exclusively as a starter, and went 10-10 with an ERA of 3.27. Blue was a free agent after the season and signed with the A’s for 1987, but abruptly retired during spring training. It was rumored that he had tested positive for drugs and retired rather than face another possible drug suspension. In announcing his retirement, Blue suggested that he still struggled with drug addiction, stating, “I reached the point where I had to choose between baseball and life.”9 In an autobiography published in 2011, he indicated that he had struggled with substance abuse for much of his career: “Along with all the glory that I’d achieved, there was a growing darkness reaching for me. And the light began to dim as early as 1972.”10 It makes one wonder what his career might have been but for his struggle with drugs.

In 1992 Blue became eligible for election to the Baseball Hall of Fame. He received a modicum of support in the four years he was considered, with his highest vote total, 8.7 percent, occurring in 1993. He was automatically removed from the ballot in 1995 because of his low vote totals. Some have wondered why Blue did not receive more serious consideration for the Hall of Fame, considering that his career numbers are quite similar to those of his former teammate, Hall of Famer Catfish Hunter. Perhaps the negative impressions created by his drug problems led to his lack of consideration. Regardless of his worthiness for the Hall of Fame, Vida Blue was one of the top pitchers of his time. In his 2001 Historical Baseball Abstract, Bill James ranked Blue as the 86th best pitcher in the history of baseball. Blue finished his career with 209 wins and 161 losses, 2,175 strikeouts, three 20-win seasons, a Cy Young Award, and a Most Valuable Player Award in his 17-year major-league career.

After retirement Blue retained a close association with baseball. He played in the Senior Professional Baseball Association in 1989 and 1990. He became active in philanthropic work, and spoke to a number of audiences about his struggle with substance addiction. Most recently, Blue served as a television analyst for the San Francisco Giants.

Postscript

Vida Blue died at the age of 73 on May 6, 2023. The cause was complications stemming from cancer, according to a statement released by the Oakland Athletics.

Sources

Blue, Vida, as told to Marty Friedman, Vida Blue: A Life (Nashville, Indiana: Unlimited Publishing LLC, 2011).

Clark, Tom, Champagne and Baloney: The Rise and Fall of Finley’s A’s (New York: Harper and Row, 1976).

Clark, Tom, Baseball: The Figures (Berkeley, California: Serendipity Books, 1976).

Clark, Tom, Blue (Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press, 1974).

Clark, Tom, Fan Poems (Plainfield, Vermont: North Atlantic Books, 1976).

James, Bill, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001).

James, Bill, and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide To Pitchers (New York: Fireside, 2004).

Kuhn, Bowie, Hardball: The Education of a Baseball Commissioner (New York: Times Books, 1987).

Libby, Bill, and Vida Blue. Vida: His Own Story (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1972).

Markusen, Bruce, A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s (Haworth, New Jersey: St. Johann Press, 2002).

Neyer, Rob, and Eddie Epstein, Baseball Dynasties (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2000).

baseball-reference.com

Notes

1. Bill Libby and Vida Blue, Vida: His Own Story, 16.

2. Libby, 20.

3. Libby, 43-45.

4. Libby, 49.

5. Libby, 51.

6. Libby, 231-248.

7. Ron Fimrite, “Vida’s Down With the Growing-Up Blues,” Sports Illustrated. September 10, 1973.

8. Ron Fimrite, “Bowie Stops Charlie’s Checks,” Sports Illustrated, June 28, 1976.

9. Ron Fimrite, “Oakland A’s Pitcher Vida Blue,” Sports Illustrated, May 19, 1997.

10. Vida Blue, as told to Marty Friedman, Vida Blue: A Life, 55.

Full Name

Vida Rochelle Blue

Born

July 28, 1949 at Mansfield, LA (USA)

Died

May 6, 2023 at Tracy, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.