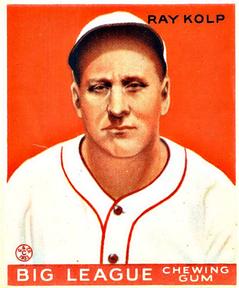

Ray Kolp

Ray Kolp had an average fastball that appeared better when used in tandem with his assortment of spinners, most notably a curveball. His greatest talent came as a bench jockey. Blessed with a high tenor voice, he could easily get an opponent’s attention from the bench. But Kolp took it one step further. Veteran catcher Clyde Sukeforth said he was “[t]he best needler of ’em all. Most jockeys worked from the bench, but Ray could work from the mound.”1 Player and minor-league executive Rosy Ryan said, “Kolp … stayed …12 years and he didn’t have a thing but a nasty disposition. He got you so mad at him that you went up to the plate with one thing on your mind. You were going to knock that ball right down his throat.”2

Ray Kolp had an average fastball that appeared better when used in tandem with his assortment of spinners, most notably a curveball. His greatest talent came as a bench jockey. Blessed with a high tenor voice, he could easily get an opponent’s attention from the bench. But Kolp took it one step further. Veteran catcher Clyde Sukeforth said he was “[t]he best needler of ’em all. Most jockeys worked from the bench, but Ray could work from the mound.”1 Player and minor-league executive Rosy Ryan said, “Kolp … stayed …12 years and he didn’t have a thing but a nasty disposition. He got you so mad at him that you went up to the plate with one thing on your mind. You were going to knock that ball right down his throat.”2

Rodney Dangerfield made a living decrying the fact that he “never got any respect.” Early in his career Ray Kolp earned respect and headlines, but for some reason his name was often garbled. He returned from World War 1 to his home in Ohio and played semipro baseball. Newspapers in Akron and Canton called him Jack Kolp in 1919. He joined the Akron Numatics (aka Buckeyes) of the International League in 1920 and appeared in the papers as Ray (and occasionally Jack) Culp. He was labeled “Ralph” Culp when he jumped the team in late August.3He joined the St. Louis Browns in 1921 and the newspapers all finally agreed that he was Ray Kolp. When he died in 1967 he still “got no respect”; The Sporting News managed to misidentify his hometown and place of death.4

Raymond Carl Kolp was born in New Berlin, Ohio, on October 1, 1894. Because of anti-German sentiment during World War I, the town would change its name to North Canton in 1917. The Kolp family lived in Belgium in the 1840s and had 17 children. From 1848 to 1851, three of the Kolp boys emigrated to New Berlin. The first was Ray’s grandfather Nicholas, who was a shoemaker. He wed Catherine Weisz. They welcomed Ray’s father, Peter Frank Kolp, in 1866.5The latter two arrivals, Henri and Louis, wed sisters of Catherine.

Peter Kolp wed Elizabeth Edington and the couple had two boys and two girls. Ray was the third child. Elizabeth was a very proper and refined lady. Ray was known as a sharp dresser, perhaps the influence of his mother. His father worked as a pad maker, probably for the local leather/harness business. That firm became the Electric Suction Sweeper Company around 1910 and then the Hoover Company in 1922. It was the preeminent employer in town for six decades.

Ray attended three years of high school before going to work for Hoover. He began playing for the town team as early as age 14 as a shortstop and pitcher. A right-handed thrower and batter, he would grow to 5-feet-11½-inches tall and play at 180 pounds.6

World War I swept up Kolp. He was given infantry training before being sent to Camp Sherman in Chillicothe, Ohio. Camp Sherman was a major training facility and Kolp most likely was involved in preparing troops for combat. He rose through the noncommissioned ranks and was mustered out as a sergeant late in 1918. Upon his return to North Canton, he moved into the family home and worked at the Hoover Company as a machinist.

Kolp’s personal life is as tricky to follow as his array of first names. According to records on ancestry.com, he was married to Ruth V. Williams on June 14, 1913.7 The couple had a son named Richard (aka Dick), born in 1913 (possibly on May 23). When Dick broke into minor-league baseball, he listed his birth as 1917.8 He would not be the first ballplayer to shave a few years off his age. In his case, he played semipro baseball in Cincinnati before joining the Paducah Indians in 1939-40 as a pitcher and first baseman.

The timing of Richard’s birth and the marriage of Ruth and Ray suggest a stressful start to the marriage. Matters got worse; the Canton Repository ran a story saying that immediately after the wedding Kolp deserted his wife. Three days after the ceremony she had not heard nor seen him.9 How the situation played out is unknown, but on January 21, 1919, Kolp filed for divorce on the grounds that Ruth was absent from the home.

Kolp’s Hall of Fame questionnaire lists a marriage to Bertha Willett on October 4, 1920. He and Bertha would be childless.10Kolp’s baseball persona carried over into everyday life. Rival players had poked fun at him for being cold, like an iced drink. He was not affectionate or particularly loving. In contrast, Bertha was much more warm and caring.

In 1919, Kolp was an integral part of the Hoover Sweepers baseball team. He and many of his teammates also played in the Akron leagues as the Gaylords. The National Baseball Federation was a loosely knit association of cities and towns from Chicago to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, that sponsored a championship for their top local teams. In 1919 the Sweepers emerged as NBF champions. In the championship game, a 14-inning, 6-5 win over Ambridge, Pennsylvania, Kolp opened the game at shortstop, but earned the victory on the hill in relief.

His performance attracted the attention of manager Dick Hoblitzell of Akron in the International League. Most of the Numatics roster were players who had already tasted life in the majors. The outfield of Jim Thorpe, Jimmy Walsh, and Joe Shannon had seen action in over 800 major-league games. Kolp was not the youngest member of the Akron team, but he was the only player who saw action in the majors after 1921.

Kolp had two offers for 1920; he was courted by Akron and the Detroit Tigers. Akron offered $300 a month to entice him to sign. Hoblitzell wasted no time in testing Kolp. The season opener against Reading was a slugfest and Kolp entered the game in the seventh as the third Akron pitcher. In the ninth, Kolp had runners on first and second with one out. He coaxed an infield grounder and potential double play, but second baseman Pete Shields made a wild throw to first, allowing the winning run to score in the 11-10 affair.

Kolp was a utility player for Akron. His next appearance was at first base. Besides his debut he had three notable games. On June 7, while playing shortstop, he launched two home runs in a 7-4 win over Rochester. He followed that up on June 20 with home runs in each game of a doubleheader with Syracuse. He made four errors in the first game, but Akron still won, 14-9. Coincidentally, during that same stretch, Babe Ruth hit four home runs for the Yankees.

Kolp’s best day on the mound came on July 28, when he was summoned from the bullpen with the Numatics down 4-0 in the third inning against Buffalo. The Buckeyes had the bases loaded and slugging catcher Frank Bruggy at bat. In 1921 Bruggy would bat .310 for the Phillies, but on this day, “like the mighty Casey of fiction, Bruggy was fanned.”11Kolp allowed only three hits the rest of the way. He poked a single to drive in the lead run, then scored. In the seventh, he made a sensational catch on a line drive headed toward center. Akron triumphed 7-4. For the season, Kolp batted .234 and posted a 4-5 record.

The same feistiness that made Kolp a caustic and effective bench jockey proved to be his undoing with Akron. Not pleased with his utility role, he threatened to jump the team on several occasions, but was always persuaded to see it through. Finally, on August 28 he left the team and returned home. That weekend he pitched for the Massillon Agathons. The Central Steel Company team was the state semipro champ and reportedly offered him $800 to play the rest of the season with them.12 Kolp was unaware that Hoblitzell had an offer from Clark Griffith and the Senators to purchase him at the end of the season. He had also been scouted by the Yankees and Red Sox.

Kolp made two relief appearances for the Agathons, earning the victory on August 29. The team then signed Al Leake from the PCL and Kolp disappeared from box scores except for a lone pinch-hitting appearance. By jumping from Akron, Kolp was technically an “outlaw” and had to reapply to play in Organized Baseball again. This usually involved a fine, but Kolp signed with Akron and avoided fines. There were indications he might have also signed a contract with Terre Haute.13 In March 1921, he was one of 19 pitchers St. Louis Browns manager Lee Fohl brought to the Browns training camp. Akron had transferred his rights to Fohl, who planned on looking at the rookie and then sending him to Terre Haute. Kolp performed so well in camp that he made the team.14

On March 25, Fohl split his troops and left training camp in Bogalusa, Louisiana. The “second team,” including Kolp, went to Memphis for a series of exhibitions. The veterans went to New Orleans for games with the Dodgers, Giants, and Pelicans.15Both squads then went north for the season opener in St. Louis against the World Series champion Cleveland Indians.

Kolp was selected to start the fourth game of the series against George Uhle. Uhle was in his third season, having graduated from the 1918 NBF champion Cleveland Standard Parts. The Browns jumped out to a 4-0 lead after two innings. Kolp kept the Indians hits scattered until the ninth. At the plate he dropped two singles into right field, scored twice, and had a sacrifice. With the Browns up 7-3 to start the ninth, second baseman Bill Gleason made an error. A double scored the run and then Kolp issued his lone walk of the game. Urban Shocker came into the game and allowed the two runners to score, but closed out the 7-6 win.

Kolp took on the role of back-of-the-rotation hurler/reliever with the Browns and later had the same status with Cincinnati. In only one season, 1928, would he fill the spot as third starter and take regular turns on the hill. He posted an 8-7 mark as a rookie and counted a 1-0 win over the White Sox on June 30 as one of his better showings. He also had the honor of joining his Browns teammates for a visit to the White House that summer.

Led by George Sisler’s .420 batting average the Browns made a serious run at the pennant in 1922. Kolp posted his finest record, 14-4, by dropping his ERA about a point lower than his rookie year. He was especially adept at beating Cleveland. After dropping his first start to them, he won his next four, including a 9-0 four-hitter on June 28. The Browns’ pennant hopes died when they lost four of five to New York and Washington from September16 to 20. Kolp made two scoreless relief appearances, but no starts in that stretch. The Browns ended the season one game behind the Yankees.

The Browns finished fifth in 1923. Kolp’s use was erratic. After two relief appearances in April, he suddenly started three games from May 1 to May 7, losing them all. After a relief appearance, he then went three weeks without any action. In late August he joined the rotation and went 3-6 with a shutout of the White Sox to his credit. He ended the year 5-12. The Browns showed little improvement in 1924. Kolp started the year as the fourth starter, but lost his spot in early May. He was relegated to mop-up duty by August. He pitched only 96⅔ innings and saw his ERA swell to 5.68. Over the winter, he was packaged with other players and traded to the American Association’s St. Paul Saints for catcher Leo Dixon.

The Saints were a veteran outfit managed by Nick Allen coming off a championship season. Kolp quickly established himself as the ace of the staff when Cliff Markle and John Merritt floundered. Kolp threw a whopping 302 innings and won 22 games with a 3.78 ERA to help the Saints to a third-place finish. The Saints overhauled the pitching staff for 1926. They kept Kolp and Oscar Roettger and brought in George Pipgras and veteran Ferdie Schupp. The Saints lineup was greatly altered as they sent catcher Pat Collins and Mark Koenig to the Yankees and jettisoned Cedric Durst. Pipgras had a marvelous season, leading the team in innings pitched and wins. Kolp’s ERA was second best on the squad, but the Saints finished sixth in the standings. Kolp was sold to Cincinnati over the winter.

The 1926 Reds finished in second place for manager Jack Hendricks. In 1927, Kolp was added to their veteran pitching staff that featured Dolf Luque, Eppa Rixey, and young Pete Donohue. Carl Mays had won 19 games in 1926 and led the team in ERA. It proved to be his final glory and he was little used in 1927. The offense was seventh in runs scored and was outhomered by both Hack Wilson and Cy Williams 30-29, not to mention finishing 31 homers off The Babe’s pace in the American League. The team finished in fifth place. Kolp did have an opportunity to perform in front of family and friends in June. The Reds played an exhibition game in Canton, Ohio, against the local Ohio-Pennsylvania League entry. Kolp tossed a five-hitter in the 11-0 win.

Kolp became the number-three hurler in 1928 and led the Reds in ERA. He also finished three games in relief that would be called saves today. The team finished in fifth place again. The following season Kolp was dropped to spot starter/reliever. His spot on the bench gave him plenty of opportunity to perfect his sarcastic attacks on the opposition.

Some bench jockeys made it a point to belittle the rookies, but Kolp seemed to pick veterans as his targets. He got under Ruth’s skin while in the American League. Ruth got a small measure of revenge for the taunting when he launched two home runs off Kolp on August 5, 1923. Now in the National League, Kolp made John McGraw a frequent target. He got McGraw’s attention by calling him Mugsy, a nickname McGraw disliked.

The most reported incident of Kolp’s needling came on July 4, 1929. Hack Wilson had singled and while he was on first Kolp shouted from the bench, “You were pretty lucky to get that hit. If I had been pitching you wouldn’t have made it. You couldn’t get a hit off me in a month.”16 The Chicago Tribune reported that Kolp even dared him to come into the dugout.17 Suddenly Wilson sprinted from first base and attacked Kolp in the dugout. Kolp suffered a black eye and both players were escorted from the ballgame.

As luck would have it, both teams were taking the Gotham Limited from the station that evening. Wilson made it known that he was going to come to the Reds’ coach and make Kolp apologize. Teammate Pete Donohue warned him that coming into the car would be a mistake. Donohue took two blows from Wilson and went down before club officials could break them apart.18 President John Heydler of the National League fined Wilson $100 and suspended him three games.19After a hearing, he censured Wilson for fighting in public, but did not add additional fines or suspensions for the Donohue fight.

In 1930, under the direction of Dan Howley, the Reds fell to seventh place. In 1931 and 1932 they occupied the cellar. Kolp had remarkably similar losing records and innings totals over those three seasons. He was joined by brash Leo Durocher and the duo made life miserable for opposing players’ ears, but the bench jockeying did not produce victories. Donie Bush took over as manager in 1933 but the results were the same. Kolp’s last season was 1934 when he pitched a mere 61⅔ innings. On February 12, 1935, the Reds released him.

The Cincinnati experience fit perfectly with a saying that Kolp had about player’s talents. His pet expression was “[y]ou can’t make chicken salad out of chicken feathers.”20 The Reds would not post a winning mark until 1938.

Now nearly 40, Kolp signed with the Minneapolis Millers in the American Association. He posted 11 wins in 1935, but then had a dismal 2-7 mark with a 7.56 ERA in 1936. He appeared with three teams in 1937-38, then returned to Minneapolis as a coach from 1939 through 1942. He served as first-base coach as well as pitching instructor. The Millers made the playoffs the first three seasons, but fell short of championships.

As a coach, Kolp turned from bench jockey to cheerleader. The local newspapers likened his voice from the first-base box to a loud speaker. He was fond of booming out encouragement, “Come on, the Millers always have a big inning”21 was his favorite phrase. The 1942 team was a second-division ballclub. Over that winter Kolp took a defense job with a business called Northern Pump as he had the previous offseason. He spent 1943 out of baseball working for the the company.

Kolp returned to the diamond in 1944 as manager of the Williamsport Grays in the Eastern League. Playing talent was slim during the war years and the Grays had a working agreement with the Washington Senators. The Senators sent 13 players from Cuba and Mexico to the Grays. This created a language barrier for Kolp that he overcame by hiring 19-year-old Manuel de la Rios as clubhouse boy and translator. The Grays did not reach the playoffs, but Kolp became a fan favorite. On August 2, the Williamsport Community Baseball Association staged a “Ray Kolp Night” and made special presentations between games of a doubleheader with Albany. Mrs Kolp received a large bouquet of orchids. Kolp was presented with a $1,000 War Bond and his players presented him with a trophy. Albany put a damper on the night by winning both games.

The gift of a War Bond for Kolp was fitting. A few weeks earlier, the team had staged a “War Bond night” at which contributions to the war effort were made for team members. The team raised $231,000. Kolp posted the largest sum, a whopping $42,000 pledged in his name. Kolp reenlisted with the Grays for the 1945 season.

Despite his reputation for sarcasm and a fast tongue, Kolp seldom ran afoul of umpires. Besides his ejection in the Wilson affair, he was run from the bench by Umpire Cy Rigler in 1930. The 1945 Grays opened the season strong and were in first place on June 1, but Kolp had missed a few days under doctor’s orders and the stress may have been getting to him.

On May 31 the Grays were hosting Utica with league President Tommy Richardson and pitching legend Cy Young in attendance. In the eighth inning, up a run, the Grays were rallying until Hector Arago was called out at home plate by umpire John Sammon. Kolp argued vociferously and was ejected. One of his players on the bench was ejected a few moments later. Utica rallied for four runs to win in the ninth. At some point in all this action, some of the Williamsport fans took to tossing bottles at Sammon. Oddly, the fans’ actions were not reported in the league newspapers. Richardson was swift to take action. Kolp was fined $50 for “inciting a riot.”22

The Grays’ season crumbled after that. They posted a 39-76 mark the rest of the way to finish in last place. Kolp chose not to return and joined Tom Sheehan and the Minneapolis Millers as pitching coach. He also directed traffic at first base. The Millers finished fourth and dropped the first round of playoffs to Indianapolis. Kolp left baseball after the season and moved back to Cincinnati.

The Kolps settled on the northside of Cincinnati in the Carthage area. Kolp took a job as a watchman with the Ridgewood Ordinance Plant. Bertha died after a lengthy illness in 1956. Ray eventually left the factory and worked in a hardware store. He befriended the owner of a small café in the Carthage sector near his home. Kolp enjoyed her company and left some of his memorabilia, including his lifetime pass, with her family.

Kolp died on July 29, 1967, in Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati. He and Bertha are buried in St. Stephen Cemetery in Fort Thomas, Kentucky. Kolp left his son, four grandchildren, and one great-grandchild. Former sports editor Tom Swope said simply of Kolp, “He was never a great pitcher, but a smart one and a hard worker.”23

Sources

Thank you to Roger Kolp, who administers the raykolp.com website. He shared the results of research and most importantly conversations with family and friends of Ray. Baseball-Reference was the source for statistics. The first edition of The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball was used for team records.

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside, 2004), 269.

2 Dick Cullom, “Cullom’s Column,” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), January 28, 1954: 14.

3 “Culp Jumps Team,” Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, August 31, 1920: 11.

4 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, August 12, 1967: 38. The article has Kolp dying in New Orleans and growing up in Kent, Ohio.

5 raykolp.com has done a marvelous job of collecting photos and information on the family.

6 The physical numbers are from the Hall of Fame questionnaire that Kolp filled out. It should be noted that on a form for Baseball Magazine he listed himself as 6-feet, 175.

7 search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&dbid=61378&h=902205599&tid=&pid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=VjY471&_phstart=successSource.

8 The Stark County, Ohio, Health Department does not have any record of Richard Kolp’s birth in 1913 or 1917. But as the clerk said, “Records are sketchy back then.” November 8, 2017, phone call.

9 “Girl Bride of 3 Days Waits in Vain for her Ball-Player Husband,” Canton Repository, June 17, 1913: 14.

10 The 1920 census adds a bit of confusion. Conducted in January 1920, it lists Kolp’s wife as Georgia. Did he have a third wife or was Georgia a nickname for Ruth? No information was found to corroborate the census listing.

11 “Ray Culp’s Twirling and Batting Are Big Feature of Victory,” Akron Beacon Journal, July 29, 1920: 16.

12 “Jack Culp Has Sealed His Own Fate,” Akron Beacon Journal, August 31, 1920: 14.

13 “With a Stopover Privilege,” Canton Daily News, February 13, 1921: 16.

14 The Sporting News, March 17, 1921: 8.

15 “Browns Break Bogalusa Training Quarters Today,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, March 25, 1921: 14.

16 Salem (Ohio) News, April 7 ,1932: 7.

17 “Hack Wilson as Pugilist Has a Big Day,” Chicago Tribune, July 5, 1929: 1.

18 Chicago Tribune, July 5, 1929.

19 “Wilson Fined $100, Suspended for 3 Days in Kolp Attack,” New York Times, July 7, 1929: 3.

20 “How About It, Will?” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), September 4, 1943: 8.

21 “Big Innings Engineer Recent Miller Wins,” Minneapolis Star, August 18, 1954: 45.

22 “Kolp Fined $50 for Part in ‘Inciting Riot,’” Elmira (New York) Sun Gazette, June 4, 1945: 9.

23 “Former Reds Pitcher Ray Kolp Dies at 72,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 31, 1967: 29.

Full Name

Raymond Carl Kolp

Born

October 1, 1894 at New Berlin, OH (USA)

Died

July 29, 1967 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.