Tom Burr

Eight major-leaguers died while serving in World War I.1 The third of these casualties, Eddie Grant, had the longest playing career and is also well remembered because he received a plaque in center field at the Polo Grounds. The shortest career on this list belonged to Alexander Thomson Burr, a pitcher who played just one inning in center field for the New York Yankees on April 21, 1914. The Williams College alumnus played just one professional season and then went into business. After entering the U.S. Army Air Service, he was killed in an airplane accident on October 12, 1918.

Burr was born on November 1, 1893 in Chicago, Illinois. His father, Louis E. Burr, worked for a firm called Kimball Carriage, which moved from Portland, Maine to Chicago in 1877 and turned to producing automobiles. In July 1892, Louis married Emily Thomson. The couple named their firstborn son for Emily’s father, Alexander MacQueen Thomson, who emigrated from Scotland to the U.S. in 1854 and became a coffee and spice merchant.2 The Burrs had one other child, a boy named Kimball. In 1905, Louis left Kimball Carriage (where he had been secretary, treasurer, and manager) and became the president of Woods Motor Vehicle Company of Chicago.3 Electric and hybrid cars have become a hot item in recent years, but Woods Motor produced battery-driven vehicles between 1899 and 1916 and introduced a hybrid in 1915.

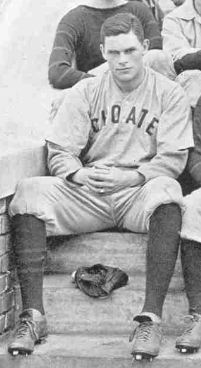

The Burrs must have been well to do, for they could afford two servants and to send their sons east to prep school and college. Baseball references have shown Burr’s nickname as Alex, but in the course of this research, nearly all contemporary references showed that the young man was known as “Tom” or “Tommy.” He first spent a year at Hotchkiss School, but in the fall of 1911, he transferred to another academy in Connecticut, Choate. He made the football team in 1911, then played shortstop and pitched for the baseball team in the spring of 1912.

In November 1913, a nearby newspaper, the Meriden Morning Record, wrote a feature full of praise for “the pride of Choate School,” looking ahead to the prospects for his collegiate career. The article said, “His record for 1912 was one to be proud of, but in 1913 his performances were even more spectacular.” To summarize, as a senior Burr allowed no earned runs and only 32 hits in 11 games, with 185 strikeouts and just 18 walks. The Morning Record added, “He was the biggest man at Choate this year as its leading athlete.”4

As former headmaster George St. John recalled in his 1959 memoir, Forty Years at School, Burr also founded St. Andrew’s Society at Choate in 1913.5 This was a non-denominational religious group; at the time, the school’s chapel was called St. Andrew’s (Burr probably enjoyed the coincidental link to his Scottish grandfather). Its members — who later included Adlai Stevenson and Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. — “contemplated the meaning of such concepts as sincerity, loyalty, and moral behavior.”6 The society also operated a camp for underprivileged boys from New York, which was staffed by Choate students. It lasted until 1965.

Of extra special interest in the Morning Record article was the endorsement of Hall of Fame pitcher Ed Walsh. Walsh, then playing with the Chicago White Sox, lived in Meriden during the off-season. His friends there sent him word of Burr. In the summer after he finished at Choate, the prospect got to work out with the White Sox (they took care not to jeopardize his amateur standing). Big Ed Walsh said, “As he was under my personal supervision I know pretty well what he has and what he can do, and I do not hesitate to say that he is one of the most promising ballplayers I have ever seen. He is a big, strong boy with a fine arm and lots of stuff. He has, I think, as much speed as anyone I have ever seen. Best of all, he is young, a willing worker, and anxious to learn.”7

By then Burr was a freshman at Williams; his choice of colleges may well have been influenced by his coach at Choate, Harry Blagbrough, a 1907 grad. His reputation as an athlete also included swimming and golf.8

A couple of months later, in January 1914, Sporting Life carried an item saying, “A.T. Burr, a phenomenal schoolboy pitcher, was also signed by the New York Americans. . .Burr is a right-hander, six feet two inches tall, and weighs 190 pounds.”9 In its next issue, Sporting Life followed up with a snippet saying, “‘Doc’ Barrett, trainer of the New Yorks, is sounding the praises of A.T. Burr, the Williams College pitcher he snared for [player-manager Frank] Chance under the very maws of Hughie Jennings and Connie Mack.”10 In addition to Philadelphia, reportedly the Chicago White Sox and Boston Red Sox were also bidding for the services of Burr, “who, it is said, has never lost a game.”11

Only nine Williams Ephmen have ever played in the majors, and none since 1934. Yet four of those nine made their debut in a span of just three years, from 1911 to 1914. It is no coincidence that three — Burr, George “Iron” Davis, and Paul “Bill” Otis — played for the Highlanders/Yankees. Charles “Doc” Barrett (a.k.a. “Bonesetter”) served double duty as trainer for both Williams and New York, joining the big-league club in 1910.12 Barrett only ever saw Burr in practice at college, though, as well as a fall series between freshmen and sophomores.13 The pitcher turned pro before he got into a college game.

It is also likely that Burr, as a Chicago native, fondly remembered Frank Chance from the first baseman’s great days with the Cubs several years before. The Providence Evening News wrote, “He turned down offers from at least three major league clubs, to play under Chance’s direction.” That report added, “Arthur Irwin [another Yankees scout] says that Burr is one of the best natural pitchers he has ever seen, and predicts a brilliant future for him.”14

Burr didn’t rely on his fastball alone. “According to Charlie Barrett, Burr throws a natural curve on account of a bend in his right arm. This bend is not the result of a break, but is simply due to the fact that the young man’s arm chose to grow in a curve rather than in a straight line. The drop, which most pitchers find difficulty in throwing, is easy for Burr. His team-mates have christened him ‘The man with the bowlegged arm.’”15

One of Burr’s personal diaries, with entries for February 27 through June 6, 1914, remains in existence. On the site that offered the volume for sale, the description noted, “Because he was a literate writer, Burr conveys what it was like to be brought into the Yanks as a highly sought after prospect, moving around with the team, spending time with his teammates, getting scolded by the team’s manager, getting paid for doing nothing, etc. Burr writes a daily log of what he did, saw and thought, including his growing increasingly tired of sitting on the bench, noting teams and scores of various Yankee games, rainouts, eating out with friends and teammates, batting practice, going to plays, who he is dating, killing time by playing cards, gambling, traveling by train and bus, playing at the Polo Grounds, working out, what time he woke up, etc. At the back he notes daily expenses such as car fare, haircuts, food, cigarettes, etc.”

Before this remarkable document surfaced, however, glimpses of Burr’s time in pro baseball were visible in the newspapers. The Yankees trained in Houston, Texas in the spring of 1914. Burr caught the team train in Memphis after riding down from Chicago. Even though a sprained ankle sidelined him for a while, the newcomer impressed Chance. In a March game, “under Chance’s personal supervision, the Yannigans [rookies] roasted Houston [of the Texas League] to the tune of 9-4, with Burr, [Ray] Caldwell, and [Marty] McHale as chief undertakers.”16

In mid-March, the New York Herald reported, “Charlie Barrett. . .in a letter to the club offices here, says that his protégé, Alexander T. Burr, erstwhile Williams college student, will stick. . .Burr is a right hander who works with a free swing and little wasted motion.” This report was also accompanied by a photo of 12 Yankees pitchers in a line, observing that 10 of them were six-footers.17

Later that month, Chance announced that two rookies — Burr and Guy Cooper — had indeed made his club. “I will keep Burr around, as I want to look him over more than I have,” said The Peerless Leader.18 He added, “I think both Burr and Cooper are good prospects. They may need some experience, but I think it would be a good idea to keep them around to see how things go in the big league. I like their style. Both have speed and seem to know more about pitching than the average hurler breaking into the big league.”19

W.J. McBeth of The Sporting News was more critical: “Tom Burr, the Williams College offering, is still too green for fast company. He has a lot of natural ability, but too green to know how to use it. He pitches to all batters alike and keeps too close to the center of the plate. Two years from now he should be a wonder, if he behaves and is properly schooled.”20

On April 19, the Yankees played an in-season exhibition game against the Newark Indians. Burr lost a 4-2 decision. The very next day, Burr’s namesake grandfather died. The day after that, at the Polo Grounds, Burr made his only major-league appearance. The Washington Senators took a 2-0 lead into the ninth inning, but then the Yankees rallied. With one out, Jimmy Walsh walked and pinch-hitter Bill Reynolds singled. Center fielder Bill Holden then brought Walsh in with a single, and Chance inserted two pinch-runners, including himself — it was the Hall of Famer’s last action as a player in the majors. New York got the tying run in, and with all the substitutions he had made, Chance had to bring Burr off the bench to replace Holden in center. (Ed Walsh had noted that Burr could handle himself in the outfield and at bat.) The rookie did not field any chances, and then the Yankees won it in the bottom of the tenth before his turn in the batting order came up. Burr’s diary entry for the day was brief and matter-of-fact. It started by mentioning “Received wire from Dad about grandpa” and did not go into any detail about his game action. It concluded “Movies and bed early.”

In late May, New London (Connecticut) in the Eastern Association acquired Burr, as he was sent out with an eye toward rejoining the Yankees later in the season. In his diary entry for May 27, Burr wrote, “Mr. Chance called me into his office and wants me to go to New London for the summer to get some actual experience and lots of work. Told him I would think it over and let him know to-morrow. . .Think I will go all right.”

Shortly thereafter, Burr returned to Choate. It was Commencement Day, and there was an array of festivities, including a student-alumni baseball game. At first, he “stated to friends in town that he did not care to pitch Saturday’s game but would be pleased to watch it. He may be persuaded to don a uniform for a few innings, however, as his many friends at the school and among the alumni will of course wish to watch him in action.”21 The coaxing worked, as the young pro got on the mound. “Burr toyed with the students, struck out the first nine batters to face him and knocked out a home run for good measure. There was another large crowd of townspeople on hand to watch the sport and especially to see Burr.”22

Burr pitched in at least one game for New London, winning a 12-inning shutout on June 11. Despite walking four and hitting three more, he allowed just three hits.23 In early July, however, Planters manager Gene McCann returned the prospect to New York. The Sporting News wrote, “Tom Burr, ball tosser extraordinary, who broke into Class B Ball with an auto and a bankroll. . .had the goods but was unable to deliver.”24 On July 8, however, he got into a game as a guest at the Hotel Griswold, a summer resort in New London, coming on in relief after the employees’ team had knocked out the guests’ starter.25

After that, Burr was assigned to the Jersey City Skeeters of the International League. There he appeared in seven games, going 0-1 while allowing 10 runs in 19 innings pitched. He struck out nine but was quite wild, walking 20. When he walked six men and hit one in three innings in the second game of a doubleheader at Toronto, the Toronto World called him “wilder than the proverbial March hare.” The man who relieved him that day was the great Cuban pitcher Adolfo “Dolf” Luque.26

A few days later, when Burr walked another six men against the Montreal Royals, the Montreal Daily Mail put it in these elaborate words: “The Pests passed out a pair of very mediocre pitchers, in the persons of Messrs. Bruck and Burr. Neither of these gentlemen were able to puzzle the local batsmen, and their extreme generosity in the matter of free tickets to first was of very great assistance to the local cause.”27

Information is lacking on Burr’s choice to quit pro ball after 1914. Accounts also differ as to whether he returned to Williams. A Chicago Historical Society publication reported that he was a student there at the time of his enlistment in 1917, but the Williams yearbook for 1915 lists him among “sometime members” of the Class of 1917. In addition, the College’s obituary record for 1918-19 stated that he entered business in Chicago after his brief experience as a ballplayer. His draft registration also showed that he was working for the American Radiator Company, a forerunner of the well-known plumbing and fixtures company American Standard. His passport application called him a salesman.

Burr entered the First Officers’ Training Corps at Fort Sheridan, on the shore of Lake Michigan near Chicago, but he was discharged after a severe attack of double pneumonia. He tried for the second camp but was rejected because of his age. Nonetheless, he was determined to serve.

Burr’s passport application shows that he was slated to join the American Field Service, one of the units of “gentlemen volunteers” who drove ambulances. The AFS recruited heavily on college campuses, including Williams. Many of the young men had to learn to drive first, but given his father’s background in the auto industry, Burr was prepared already. “Privately financed, he went to France as a truck driver, but finding that older men were doing this work, he felt that it would be unpatriotic to continue, and enlisted at once with the American aviation corps.”28

The U.S. Army Ambulance Service absorbed the AFS on August 30, 1917. There was already a strong connection between the AFS and both the French and U.S. Air Service. The latter, forerunner of the U.S. Air Force, was then an army unit. Burr was a member of the 31st Aero Squadron. He went first to the American flying school at Issoudun in central France (where “Ace of Aces” Eddie Rickenbacker was the engineering officer). “It is said that he went through his course without bending a wire or breaking an axle.”29

Gill Robb Wilson, who later founded the Civil Air Patrol, remembered Burr in his memoir. They and several other pilot cronies “developed a routine of frequently inviting one or the other of our French instructors for dinner at a farmhouse near the tiny French hamlet of Vouvray. The old couple who lived there would roast a half-dozen chickens, fry up a mess of potatoes and come up with truly vintage ‘Vouvray, ’84.’”30

Burr also still did a little pitching overseas. In a rundown of military games in 1918, the 1919 edition of Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide showed that on June 23, he struck out 21 batters for the Aviation Instruction Center team, which handed another post team, St. Pierre de Corps, its first defeat.31

After completing his acrobatic training at Issoudun, Burr was ordered back to Tours to serve as instructor in preliminary training. From there he became a member of the staff of instructors at Issoudun. He passed his examination for the rank of first lieutenant and was on his way to the front. Before that, however, he made a brief but fateful stop.

From Issoudun, many new pilots went to Cazaux, in the southwestern part of the country, near Bordeaux. There, amid the pine-covered wastelands of the Landes de Bussac, was a gunnery school called École de Tir Aérien, which supplied additional training to the flyboys in their Nieuport biplanes. Targets were towed across Lac de Cazaux, a 21-square-mile local lake.

Colonel Edgar S. Gorrell’s History of the American Expeditionary Forces Air Service, 1917-1919 noted, “Several fatal accidents marred the work at Cazaux. . .the school was famous for its many narrow escapes.” The next page revealed how Burr’s life was cut short at the age of 24, just 30 days before the armistice that ended World War I. “On October 12th, 1918, occurred the worst accident in the life of the school at Cazaux, when pilots Burr and Kennedy collided at an altitude of 4500 feet while shooting on the sleeve target and fell into Cazaux lake at its deepest part, each with one wing fluttering down after. One fuselage was discovered, and twelve days later the body of Lieut. Burr came to the surface, but neither the machine nor the body of Lieut. Kennedy could be found, although every possible effort was made to locate it, from the air, in boats, and by diving.”32

George St. John wrote, “When I had to tell Tom’s brother Kim, Kim said, ‘I won’t believe it. That kind of thing doesn’t happen to Tom!’”33A letter from one of his comrades echoed the feeling. “At the field, we just can’t believe it. We know it was absolutely unavoidable because Tom was a perfectly wonderful flyer. His skill was the marvel of every man who saw him in the air.”

The Chicago Tribune article describing the accident was published before Burr’s body was discovered. Various baseball reference sites focused on this article, and as a result, the idea persisted that he was never found. In fact, another report in the Tribune the following March described how the Red Cross responded to the pleas of Louis and Emily Burr, locating and decorating their son’s gravesite. This article did not specify the location — but it was almost certainly a spot called Le Natus, between the town of Arcachon and Lac de Cazaux. Two small cemeteries were established there during the war. One held 940 men from Senegal, as well as 12 Russians. The other, American Expeditionary Forces Cemetery No. 29, was for Americans stationed at Cazaux who had died of the Spanish flu or in training exercises. The forested location tallies with the photo accompanying the March 1919 article.

During the years after the end of World War I, the American cemetery was deconsecrated. Some of the bodies exhumed — including Burr’s — were repatriated, while the rest were re-interred at the American military cemetery of Suresnes, outside of Paris.34 Tom Burr’s final resting place became Rosehill Cemetery and Mausoleum in Chicago.35 A marker at the Nécropole Nationale de la Teste de Buch also still commemorates the 87 Americans who gave their lives at Cazaux during The Great War.36

Acknowledgments

Continued thanks to Eric Costello and SABR member Bill Nowlin for additional research. Thanks also to Marion Bastien of Arcachon, France. Marion’s blog, Du Côté du Teich (http://ducoteduteich2.wordpress.com/), has carried many entries about the area’s unique World War I history.

Photo Credits

Burr in baseball uniform: Courtesy of Choate Rosemary Hall Archives

Burr in Salvation Army hat: from his passport application

Burr in military uniform: Courtesy of Williams College Archives and Special Collections

Sources

Alexander Thomson Burr obituaries:

“Flaming Plane Falls in Lake with Chicagoan.” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 18, 1918.

“Williams Pitcher Killed.” New York Times, December 29, 1918.

“A U.S. Flyer’s Grave in France.” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 30, 1919.

Obituary Record of the Society of Alumni, Williams College, 1918-19. Williamstown, Massachusetts, April 1919: 477-78.

Wood, Frederic T., editor. Williams College in the World War. Williamstown, Massachusetts: The President and Trustees of Williams College, 1926: 128.

History of the cemeteries of Le Natus, La Nécropole Nationale de la Teste de Buch, and the American Stele:

http://www.bassindarcachon.com/histoire_locale.aspx?id=170

http://ducoteduteich2.wordpress.com/2009/11/11/necropole-nationale-la-teste-de-buch-et-stele-des-americains/

Burr family background:

http://www.ancestry.com (1900 and 1910 census information, Burr’s World War I draft registration and passport application)

Encyclopedia of American Coachbuilders & Coachbuilding (www.coachbuilt.com)

Morrison, Leonard Allison. History of the Kimball family in America, from 1634 to 1897.

Burr’s personal diary:

This item was available for sale in September 2016 on the website blankverso.com (it had also been listed on eBay). According to the dealer, Steven Hill, he obtained it in an estate sale, but the family knew nothing of how it had come into their possession. While it was listed, pictures of various pages were posted; these are now in the author’s files (thanks to Steven Hill). The diary was subsequently purchased by a generous Choate Rosemary Hall alumnus, who has donated it to the New York Yankees Museum.

Others:

http://www.firstworldwar.com/poetsandprose/ambulance.htm

http://www.baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com

Notes

1 In addition to Eddie Grant and Burr, the others were Robert “Bun” Troy (killed in action in France); Ralph Sharman (drowned during training in Alabama); Larry Chappell and Harry Glenn (Spanish flu); Newt Halliday (tuberculosis/pneumonia), and Harry Chapman (died from wounds in Missouri).

2 Annual Report of the Masonic Veteran Association of Illinois, 1914.

3 The Horseless Age, November 22, 1905: 689.

4 “Ed Walsh Praises Burr, Former Big Choate Pitcher.” Meriden (Connecticut) Morning Record, November 7, 1913: 4.

5 St. John, George. Forty Years at School. New York, NY, Holt, 1959:77.

6 Baker, Jean H. The Stevensons: An American Family. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996:238.

7 “Ed Walsh Praises Burr, Former Big Choate Pitcher”

8 “The Week in Society.” Town & Country, March 1, 1919: 48.

9 “More Men for New Yorks.” Sporting Life, January 24, 1914: 3.

10 “American League News In Nut-Shell.” Sporting Life, January 31, 1914: 14. See also “Burr of Williams Signed.” Boston Globe, January 20, 1914.

11 “Bidding for a Wonder.” Sporting Life, January 24, 1914: 6.

12 “Yankees to Have Own Bonesetter.” Pittsburgh Press, July 13, 1910: 16.

13 “Williams Loses Pitcher,” Boston Evening Transcript, January 21, 1914: 5.

14 Providence Evening News, January 21, 1914: 4.

15 “Crooked Arm Is Aid to Twirler.” Mansfield (Ohio) Shield, April 7, 1914: 6.

16 Dix Cole, Harry. “New York News Nuggets.” Sporting Life, March 14, 1914.

17 “Ten of Yankees’ Pitching Corps Are Six Footers.” New York Herald, March 15, 1914: 4.

18 “Chance Bars Poker Playing in Hotels.” New York Times, March 31, 1914.

19 “Burr Is Added to Yanks Pitching Staff.” Meriden Daily Journal, March 24, 1914: 3.

20 McBeth, W.J. “Yankees Home Primed to Show Fans Something New,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1914: 1.

21 “Burr In Town.” Meriden Morning Record, May 29, 1914: 3.

22 Meriden Morning Record, June 1, 1914: 3.

23 “Planters Win in Extra Innings, 2-0, from Wings.” New London (Connecticut) Day, June 12, 1914: 13.

24 The Sporting News, July 16, 1914: 5.

25 “Griswold Guests Lose.” The Day, July 9, 1914: 9. The Day noted on July 16 that Burr left the Griswold, where he had been staying, for New York.

26 Toronto World, July 31, 1914: 10.

27 “Royals Captured Another.” Montreal Daily Mail, August 4, 1914: 8.

28 “The Week in Society”

29 Ibid.

30 Wilson, Gill Robb. I Walked with Giants. New York, NY: Vantage Press, 1968: 106.

31 Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide for 1919. New York, NY: American Sports Publishing Company: 247.

32 Gorrell’s History of the American Expeditionary Forces Air Service, 1917-1919. National Archives and records Service, General Services Administration: 75 (available online at http://www.footnote.com/document/21586732/). The accident report itself is available for purchase from the website of Aviation Archaeological Investigation & Research. The summary page for 1918 is at http://www.aviationarchaeology.com/src/1940sB4/1918.htm.

33 St. John, Ibid., loc. cit.

34 My check of the Suresnes database did not show Burr’s name. Marion Bastien also confirmed this point with Patrick Boyer, co-author of the book 1914-18 : Le Bassin d’Arcachon.

35 Lewis, Eli Robert. The Roll of Honor, Containing the Names of Soldiers, Sailors, and marines of All Wars of Our Country Who Are Buried in the Cemeteries of Cook Country. Chicago, Illinois: Printing Products Corp., 1922: 286.

36 In addition, in the Memorial House dormitory at Choate Rosemary Hall (dedicated May 30, 1921), the contents of the cornerstone and the painting in the first-floor common room honor Burr and his 15 fellow Choate alumni who made the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of their country.

Full Name

Alexander Thomson Burr

Born

November 1, 1893 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

October 12, 1918 at Cazaux, (France)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.