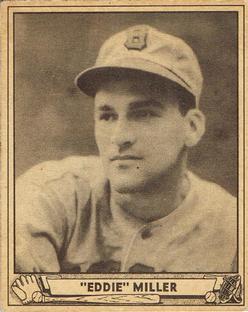

Eddie Miller

Eddie “Eppie” Miller, was, by the fielding metrics of his time, the finest fielding shortstop in the National League. He was seven times an All-Star during a career of 14 years.1 His contemporary, Marty Marion, stated that Miller was the best shortstop he ever saw.2 Eddie was always outspoken, managing to talk his way off one team with a single off-season speech, and not hiding his dislike for playing for the second-division Boston Bees and Casey Stengel.

Eddie “Eppie” Miller, was, by the fielding metrics of his time, the finest fielding shortstop in the National League. He was seven times an All-Star during a career of 14 years.1 His contemporary, Marty Marion, stated that Miller was the best shortstop he ever saw.2 Eddie was always outspoken, managing to talk his way off one team with a single off-season speech, and not hiding his dislike for playing for the second-division Boston Bees and Casey Stengel.

Edward Robert Miller was born in Mt. Lebanon, Pennsylvania, on November 26, 1916. He was one of five children, with siblings Ernest, William, Carl, and Mildred.3 Their parents were Carl and Marie (Wagner) Miller.4 Though information on Carl Sr.’s occupation is not presently available, the Miller family was poor and often did not have enough food to eat, so young Eddie often stayed with his best friend, Albert Ott.5

Miller attended South Hills High School. At first he was deemed too small for the high school team, but his desire to play led him to volunteer his time at a shoe store called Book’s so he could be on the store’s semipro team. He got a spot on the team as a bat boy but was allowed to work out with the players. A few years later, he was allowed to join the South Hills baseball team.6

Signed by the Pirates at age 17, he spent 1934 in the Class C Middle Atlantic League, hitting .286 in 122 games at shortstop for the Springfield (Ohio) Pirates. Sold to the Reds in the winter of 1934 for $1,000, he spent most of 1935 playing 100 games in the Class B Piedmont League for the Wilmington (North Carolina) Pirates, where he hit .283 with 11 home runs, and made 50 errors. He was promoted to the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League for 18 games, hitting .308. He stuck with Toronto for the 1936 season as their regular shortstop, playing 150 games with a batting average of .242, including eight home runs, with 40 errors.

In 1936 Eddie married Swan Anna Ott, the sister of his friend Albert.7 They remained together for 57 years until her death in 1994. They had three sons over the next five years — E. Robert, M. Glenn, and Gordon — and later a daughter, Carol.

Miller made his major league debut for the Reds at age 19 on September 9, 1936, against the New York Giants as a defensive replacement at second base. Not until ten days later did Miller get his first major league hit. He split 1937 between the big-league club, where he hit .150 over 36 games, and Syracuse of the International League, hitting .235 there while appearing in 75 games. At Syracuse he shared the shortstop duties with Eddie Joost. Of the two, Miller had the greater range and made fewer errors.

On December 3, 1937, the Reds sent Miller and $40,000 to the New York Yankees for Willard Hershberger, the troubled catcher who would commit suicide in his Boston hotel room in August 1940 at age 30. The Yankees sent Miller to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association for 1938, where he hit .290 with 14 home runs, while committing 33 errors in 147 games. However, the Yankees, with Frankie Crosetti playing every game in New York and Phil Rizzuto in the wings playing for the Class B Norfolk Tars, were able to trade Miller, Gil English and Johnny Riddle to the Boston Bees after the 1938 season, receiving in return Bobby Reis, Tommy Reis, Johnny Babich and Vince DiMaggio.

After a brief holdout, Miller was the Bees’ starting shortstop for the first 77 games of 1939, until he suffered a broken ankle as a result of a season-ending collision on July 16 with Bees’ left fielder Al Simmons while chasing a fly ball. Before the injury he had a .970 fielding percentage with only 14 errors, while hitting .267/.315/.361 with 31 runs batted in.

Able to play every day in 1940, Miller plated 79 runners in 151 games, had a .276/.330/.418 season with 14 home runs, and won his first selection to the All-Star Game. He duplicated his .970 fielding average, participated in 122 double plays to lead the league, and finished 13th in the MVP voting. Bees skipper Casey Stengel dubbed Miller “The Vacuum Cleaner.”

Miller was again the everyday shortstop for the Bees in 1941, although his offensive production dropped to 6 home runs and a .239 batting average. For the second consecutive year Miller was the backup shortstop at the 1941 All-Star Game. While playing for a salary of $12,500 (about $195,000 in 2018 dollars), he generated approximately the same results in 1942, finishing at .243/.279/.337 with 6 home runs. He was picked for the All-Star team for the third consecutive year and started at shortstop.

By 1942 the United States was at war, but Miller was not subject to the draft because he was supporting three young boys.8 His finest fielding season was 1942; he made only 13 errors in 748 chances, earning a .983 fielding percentage. However, Miller was dissatisfied with the salary the Bees could pay him, felt stuck in the second division, and was reported by The Sporting News as not getting along with Stengel.9 As a result of his discontent — and his 50 errors,10 Miller was traded to the Reds for $25,000, Nate Andrews, and Eddie Joost, his minor league teammate. Andrews, a frontline pitcher, was the main piece the Bees wanted.11

In 1943, playing in every game, Miller led the second-place Reds with 71 runs batted in despite his .224/.271/.293 numbers. He struck five hits at Wrigley Field on June 12, including a double and triple. For the third year in a row Miller led the league in double plays (the Reds led the National League in twin killings) and made only 19 errors. Miller made the All-Star team again, striking out in his only plate appearance, and finished 10th in the MVP voting that year.

Miller was again the everyday shortstop for the Reds in 1944, finishing at .209/.269/.289 while playing every game, and garnering another All-Star berth, while committing only 27 errors.

Miller did not play his first game in 1945 until May 26; he had split open his left knee cap while walking on ice on February 1 while hosting a party for his kids.12 Miller played in 115 games for the Reds that year improving to .238/.275/.404 with the bat, attributable in part to his 13 home runs, two of which he hit in a home game against the Phillies on September 7. He participated in five double plays in a game against the Pirates on June 24.

Miller spent January and February 1946 as an instructor (with Bob Feller) at the Ray Doan Instructional Camp in Palatka, Florida, which was free to returning veterans and youngsters.13 He was voted to the All-Star team again in 1946, but begged off. Hampered by injuries, described as a sore shoulder caused by headfirst slides,14 he appeared in only 20 games after the All-Star game. He had his worst batting year by far, achieving a .194/.258/.288 slash line over 328 plate appearances.

By contrast, 1947 was a banner year for Miller offensively; he played in all but three games, led the team with 87 runs batted in, stroked 19 home runs, led the league in doubles with 38 and posted a slash line of .268/.333/.457. Miller was selected to his seventh and last All-Star squad and finished 24th in MVP voting. He was again outspoken about not liking his manager’s tactics, criticizing Johnny Neun occasionally during the season for too much emphasis on “hit and run,” only to have other teammates repeat the disparaging remarks to Neun.15

But Miller talked himself right off the Reds when he made what he considered to be off-the-record comments to the Quarterback Club of Hamilton, Ohio, on January 12, 1948. Miller’s remarks on that date showed him to be an equal opportunity offender. In a single speech, he asserted the 1948 Reds would be lucky to tie for last place, that he preferred the managerial style of former Reds manager Bill McKechnie over current skipper Neun, and added it was unlikely that many Reds youngsters (including Hank Sauer, Grady Hatton, Benny Zientara, Frank Baumholz and Bobby Adams) would ever amount to anything on the major league level. 16

Miller spoke with Neun on January 19 to soothe tempers, but sealed his fate with the Reds by refusing to retract his prior comments when he returned to the Quarterback Club on January 26, carrying (as a joke) the Dale Carnegie book How to Win Friends and Influence People. That night he told the audience he hadn’t lost sleep over his comments and that as someone over 21 years of age he was free to make such comments.17 Combined with the disparaging remarks Miller had made during the season, these two speeches sparked Reds President Warren Giles to state Miller had decreased his value to the team, making a trade inevitable.18

Miller went to the Phillies in February 1948 for Johnny Wyrostek, who was three years younger (31 vs. 28).19 Phillies’ Manager Ben Chapman, upon learning of the trade, was quoted as saying, “I don’t care what he said, all he has to do is hit and field.”20 As the regular shortstop for the Phils in 1948, Miller played in 130 games, hitting .246/.281/.382 with 14 home runs and 61 runs batted in, including five runs batted in against the Pirates at home on June 20. Off the field, Miller was a member of a barbershop quartet with Bert Haas, Emil Verban, and Harry Walker.21 Miller even had the temerity to go back to the Hamilton Quarterback Club in May and again not truly apologize, stating he meant no harm with his remarks and that he was just stating his opinion about the Reds.22

By 1949, the Phillies, fully engaged in the youth movement that would result in the “Whiz Kids” of 1950, moved the 32-year-old Miller to second base, while Granny Hamner was the everyday shortstop. Miller had a poor offensive year, batting .207/.294/.320 with 29 runs batted in, while earning a salary of $13,500. After hitting a grand slam at home against the Giants on April 26, Miller received a television set.23 He was also part of another barbershop quartet known as the Philharmonics, along with Richie Ashburn, Russ Meyer, and Andy Seminick, who were photographed on a wagon.24 For the Phils’ third place finish in 1949, each player received $721.85.

Miller’s role on the 1950 Phillies was to serve as backup to rookie second baseman Mike Goliat, but he was placed on waivers before the season began and picked up by the Cardinals. As the backup to starter Marion, Miller appeared in only 64 games for the 1950 Redbirds, hitting .227/.307/.326. He played his last major league game on September 24 and was released by the Cards three weeks later.

No longer playing, Miller spent three winters (1951-1953) as an instructor at the Jack Rossiter Baseball School in Cocoa, Florida, named for the longtime Washington Senators scout. Tuition at the four-week school was $35 for 1953 and players could expect to spend $22 a week for room and board.25 Miller opened his own “School of Baseball” located in Del Rio, Texas, in the spring of 1954 with instruction through slow motion movies.26 For 1955 Miller’s school moved to Stuart, Florida, and he found employment as a roving instructor in the Phillies farm system that same spring and the following spring.27 Miller spent 1957 as a coach for the Miami Marlins, the International League farm club of the Phillies, only to be fired at the end of the season, ending his connection to professional baseball.

By this time Miller had lived in the vicinity of Jupiter, Florida, for many years, working at nearby jai alai frontons and becoming a scratch golfer. He died on July 31, 1997, in Lake Worth, Florida, of either natural causes (according to his Florida obituary) or a stroke (as his Pittsburgh obituary indicated). He is buried at Union Dale Cemetery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.28

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Thomas Nester.

Notes

1 The Sporting News reported on December 27, 1945 that during the last six seasons (1940-1945) Miller handled about 700 more chances than Marty Marion and made 32 fewer errors, resulting in a fielding percentage for those years of .974, some .012 better than Marion’s. During those six years Miller also had 37 more runs batted in than Marion.

2 The Sporting News, October 19, 1944, 8.

3 “Edward Robert ‘Eppie’ Miller,” Palm Beach Post, August 3, 1997, 23. “Mildred E. (Miller) Rady,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 19, 2006.

4 “Mildred E. Rady,” Pittsburgh Tribune Review, March 19, 2006.

5 “Edward R. Miller: Shortstop in Major Leagues,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 3, 1997, 32.

6 Ibid.

7 1940 census records. Anna Swan Wittmer Ott obituary, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 3, 1955, 25.

8 “Navy Calls Gremp and Sain of Braves,” The Sporting News, October 22, 1942, page 8,

9 “New Vistas for Miller and Joost,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1942, 4.

10 Dan Daniel, “Daniel’s Dope,” New York World Telegram & Sun, December 9, 1948.

11 Jack Malaney, “Eddie Miller’s ‘Rib’ Fails to Tickle Braves,” The Sporting News, January 13, 1944, 12.

12 Tom Swope, “When Miller Makes Error, It’s News,” The Sporting News, February 22, 1945, 5.

13 “Eddie Miller and Lew Fonseca to Act as Instructors at Feller’s Free School,” The Sporting News, January 3, 1946, 13.

14 The Sporting News, January 22, 1947, 2.

15 New York World Telegram & Sun, March 5, 1948.

16 Tom Swope, “Reds Burned Up by Miller’s ‘Last Place’ Talk,” The Sporting News, January 28, 1948, 8.

17 Tom Swope, “Miller Takes to Stump Again; Hatton Jumps Into Reds’ Debate,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1947, 11.

18 Swope, “Reds Burned Up by Miller’s ‘Last Place’ Talk.”

19 Tom Swope, “Miller-for-Wyrostek Deal Likely to Keep Hatton on Third for Reds,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1948, 2.

20 “Phillies Obtain Shortstop Miller From Reds,” New York Times, February 9, 1948.

21 “Miller Sounds Off — as Song Leader,” photo caption, The Sporting News, March 31, 1948, 10.

22 “Miller Mounts Old Platform with Different Kind of Talk,” The Sporting News, May 19, 1948, 37.

23 “Eddie’s First Gift for Diamond Feats,” photo caption, The Sporting News, May 18, 1949, 9.

24 “Philharmonics Off to Fast Start,” photo caption, The Sporting News, May 11, 1949, 32.

25 “Rossiter to Conduct Two Schools in Fla.,” The Sporting News, December 31, 1952, 23

26 The Sporting News June 9, 1954, 42.

27 Stan Baumgartner, “Phils Low-Run Team in Florida Till Vets Begin to Show Power,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1955, 8.

28 Thomas R. Collins and Kristin Vaughan, “Edward ‘Eppie’ Miller, pro shortstop, dies,” The Palm Beach Post, August 5, 1997, 17.

Full Name

Edward Robert Miller

Born

November 26, 1916 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

July 31, 1997 at Lake Worth, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.