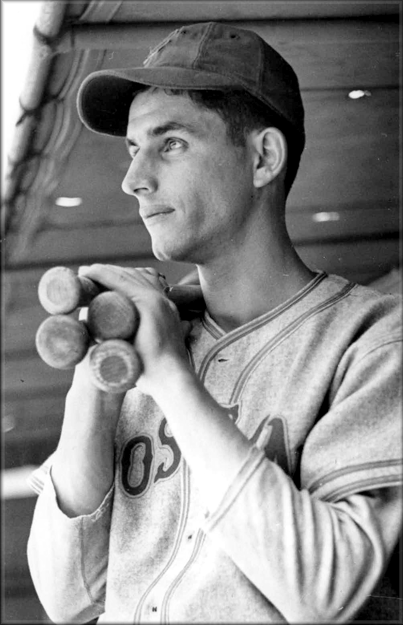

Vince DiMaggio

Nobody wrote a song about Vince DiMaggio. It was his lot in life to be outshone by his kid brothers. He’s the DiMaggio who set the single-season record for strikeouts by a batter.

Nobody wrote a song about Vince DiMaggio. It was his lot in life to be outshone by his kid brothers. He’s the DiMaggio who set the single-season record for strikeouts by a batter.

Vince and strikeouts go together like Joe and Marilyn. He led the National League six times. He didn’t deliver the home runs to justify the whiffs; his career high was 21. But he fashioned a 10-year big-league career as an elite center fielder with a powerful arm and was selected for two All-Star teams during World War II.

Most famously, Vince recommended brother Joe to the San Francisco Seals in 1932, and Joe took his job. “Maybe if I had kept my mouth shut, I’d be remembered as the greatest DiMaggio,” Vince said decades later.1 If we could hear his tone of voice, maybe we’d know whether he was joking.

The DiMaggio brothers’ father, Giuseppe, came to California from Sicily in 1898 and fished in San Francisco Bay from a tiny 16-foot boat. It took him four years to save enough to bring his wife, Rosalie, and their daughter, Nellie, to join him. Eight more children were born in California, one about every other year. Eldest sons Tom and Mike played some ball — Vince always said Tom was the family’s best player — but they dutifully took their places on the fishing boat with their father.

Vincent Paul DiMaggio, born in Martinez, California, on September 6, 1912, was the seventh child and third son, and the first to rock the boat. He aspired to be a singer, and he was a good one. Or a ballplayer. When he wanted to go to Northern California to play semipro ball, his father forbade it. Vince went anyway. When he met the girl he wanted to marry, his father forbade it. Vince married Madeline Cristani anyway. Giuseppe effectively banished him from the family.2

The 19-year-old Vince signed with the Pacific Coast League Seals in 1932 and was farmed out to Class-D Tucson. He was leading the Arizona-Texas League in home runs and batting average when the league shut down in midseason. The Seals called him up to San Francisco, and he walked into the family home unannounced. To pacify his father, Vince flashed the $1,500 he had saved. “I didn’t bring no check. I brought it in cash so he could see it was more than a piece of paper; he knows the cash, but he didn’t know anything about a check, so I had it all in cash — and the first thing he says when he saw the money was, ‘Where’d you steal that money?’”3

Vince introduced Giuseppe to his boss, Seals owner Charley Graham, who vouched that the money was earned. Hearing that, Giuseppe’s opposition to the childish game softened. He had always considered it a distraction from a man’s responsibility to provide for his family, but when youngest son Dominic started high school, his father asked, “And when are you going to play baseball?”4

Vince the handsome rebel was the son with personality. “He was always singing, full of life,” Papa DiMaggio remembered.5 Joe, as shy as Vince was voluble, began playing ball by tagging along with his big brother. He made a name for himself on the San Francisco semipro circuit. In the last week of the 1932 season, the Seals were shorthanded because they had allowed outfielder Hank Oana and shortstop Augie Galan to leave early for a barnstorming trip to Hawaii. Vince recommended Joe, not yet 18, and the brothers appeared in the lineup together for the first time. Playing three games, Joe slammed a double and a triple in nine at-bats while endangering spectators with his wild throws from shortstop.

Vince, in center field, hit .270 in 59 games for the Seals. The next spring he developed a sore arm and couldn’t throw. Joe won the right-field job, so the DiMaggios played side-by-side, but Vince lasted less than a month before he was released. The team cut several other players to reduce the payroll as the Depression held attendance down.

In probably the toughest minor league in the country, Joe was a sensation at 18 years old. Taking over in center field, he hit in 61 straight games and batted .340. Vince, picked up by the Hollywood Stars, hit .333 with 11 homers in 96 games.

Vince spent the next three seasons in the Coast League. After the Hollywood franchise moved to San Diego in 1936, he was a teammate of teenagers Ted Williams and Bobby Doerr. He earned a reputation as the league’s best defensive center fielder while batting .286 with 60 home runs over the three years. Meanwhile, Joe moved up to the Yankees in 1936 and was anointed as the successor to the retired Babe Ruth.

In December 1936 the news broke that “Vince DiMaggio, Joe’s brother,” had been sold to the Boston Bees.6 Manager Bill McKechnie, who built his teams around strong defense, wanted Vince for his center-fielding skills. Since the Bees and Yankees both trained in St. Petersburg, Florida, the brothers got together for dinner in the spring and could celebrate Dominic’s signing with San Francisco.

But the 24-year-old Vince’s wild swinging appalled his manager. “Why, that fellow DiMaggio is missing pitches by so wide a margin that I can see a foot of daylight between the ball and the bat,” McKechnie reportedly said. “I can’t understand how someone can swing at a ball so many times without even ticking it once.”7

DiMaggio struck out twice in his big-league debut and seven times in his first seven games. After he fanned four times in one game, McKechnie ordered him to choke up on the bat and shorten his swing. DiMaggio reeled off a 10-game hitting streak from May 7 through May 21, but then went 0-for-15 and fell back on his old habits.

As the strikeouts piled up and he struggled to keep his batting average above .250, DiMaggio changed batting stances as often as he changed shirts. He tried wearing glasses for a while. Nothing plugged the hole in his swing. “Vince could hit the low ball as well as anybody,” Dominic explained years later, “but he couldn’t follow the ball in a certain high spot, and the pitchers started throwing to it.”8

His rookie season ended with 111 strikeouts, most in the majors, a .256 batting average, and a weak .699 OPS. He did live up to his defensive reputation, leading National League center fielders in putouts, assists, and range factor per game as well as errors. It was no consolation that the DiMaggios set a major-league record for home runs by brothers: 13 for Vince and 46 for Joe.9

Vince set his unwanted record in 1938, when he struck out 134 times.10 He whiffed in almost 22 percent of his plate appearances, more than twice the league average. His batting average slid to .228 and his OPS to .682.

That wouldn’t do. In 1930s baseball, a strikeout was an embarrassment, 134 of them a humiliation. Babe Ruth never struck out 100 times in a season. The few who did were either fearsome sluggers — Jimmie Foxx, Dolph Camilli — or all-American outs — Frankie Crosetti. Joe DiMaggio never struck out more than 39 times in any season and often had more homers than strikeouts.

The Bees’ new manager, Casey Stengel, had seen more than enough. “Vince is the only player I know who could strike out three times in one game and not be embarrassed,” Stengel said. “He’d walk into the clubhouse whistling. Everybody would be feeling sorry for him, but Vince always thought he was doing good.”11

Not good enough. Boston packed DiMaggio off to Double-A Kansas City after the season. He had passed through waivers, a sign that there was no market in the majors for the strikeout king. “Other managers would talk a lot about some of his catches and some of the throws he made,” Bees president Bob Quinn said, “but none of them was interested enough in acquiring his services to make us a deal for him.”12

Kansas City was a Yankees farm club, but there was no chance of a brotherly reunion. The powerful rookie Charlie Keller was set to join Tommy Henrich flanking Joe in the New York outfield, and the club had George Selkirk, a lifetime .302 hitter to that point, on the bench.

Vince, shocked and angry, at first said he wouldn’t accept the demotion. He relented — he had no choice if he wanted to continue playing. He took out his frustration on American Association pitchers, slamming 25 home runs in his first 53 games. He finished the 1939 season leading the league with 46 homers and 136 RBIs. Manager Bill Meyer said DiMaggio had fixed a hitch in his swing. “I have never in all my baseball experience known a player who worked with more zeal to correct a fault,” the manager applauded.13

DiMaggio’s power splurge helped the Blues win 107 games and the pennant. And it won him another shot in the majors. The Cincinnati Reds, managed by Bill McKechnie, bought his contract for delivery at the end of the American Association season. The Reds were on their way to the National League pennant, but had outfield problems.

Vince wasn’t the answer. In eight September games, he totaled one hit and 10 strikeouts in 14 at-bats. The Reds were swept by Joe’s Yankees in the World Series, but Vince, as a late-season call-up, was not eligible to play.

Still, 1939 was a game-changing year for the DiMaggios. While Vince was slugging for Kansas City, Joe was elected the American League Most Valuable Player, Dom the Pacific Coast League MVP. In 1940 Dom, 23, joined his brothers in the majors, winning the center-field job with the Boston Red Sox.

Aside from the same dark, curly hair and a vague facial resemblance, the three were not much alike. Joe, 6-foot-2, was the greatest star on the greatest team; Vince, 5-11¾ by his own reckoning, was trying to resurrect his career; and Dom, 5-9, trying to establish his. Their personalities were just as different. “Likable and affable, Vince has a far warmer personality than either of his brothers,” wrote Arthur Daley of the New York Times. “Whereas a brief ‘uh-huh’ was a full-flowered conversation for the reticent Joe and where Dom is shy and retiring, Vince is expansive.”14 They were most similar in center field, where all were among the best in the game.

Whatever Vince had found in Kansas City, he brought it back to the majors with him. After Cincinnati passed him on to the Pittsburgh Pirates in early 1940, he put up the best numbers of his career, a .289/.364/.522 batting line with 19 homers in 110 games for the Pirates. The next year he cut his strikeout rate to 15.5 percent and registered career highs with 21 homers and 100 RBIs. He strung together a 12-game hitting streak and a pair of 10-gamers, but combined they added up to only about half of Joe’s historic 56-game streak that summer.

Vince delivered two more productive seasons, although he led in strikeouts both times. In 1943 he made his first All-Star appearance, contributing a home run, triple, and single to lead the NL to a 5-3 victory. (Joe and Dom had gone into military service; Vince was draft-exempt because of a stomach ulcer.)

But manager Frankie Frisch was growing impatient with the strikeouts and nagging him to take extra batting practice — as if that was likely to help a guy who had been fanning the air since he was a teenager. “I said so often to him, ‘Vince, throw that glove away,’” Frisch complained. “‘Get in some pepper games and get the feel of the bat. Hit every chance you get. There isn’t a better fielder in baseball than you.’ But does he do it? He does not. He grabs the glove and forgets the bat.”15

The Pirates and DiMaggio parted company over a steak. Returning to the team’s hotel after a night game in New York in July 1944, he found that the only eating place still open was the nightclub. When he ran up a $9 tab, twice the Pirates’ meal allowance, management deducted the excess from his paycheck. Incensed, he demanded a trade.16 (“Feed me or trade me”?) He spent the last two months of the season in the doghouse and mostly on the bench.

DiMaggio said he wouldn’t play for Pittsburgh again. He went to work in a California shipyard and stayed there when spring training opened in 1945. On March 31 the Pirates traded him to the bottom of the National League, the Philadelphia Phillies. “One sure way of getting to Philadelphia or other sections of the league’s salt mines is to up and say one is discontented with his present berth,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette writer Havey J. Boyle commented.17

As the Phillies slogged to another last-place finish, DiMaggio put his name in the record book again, this time for an accomplishment worth remembering. He hit four grand slams during the 1945 season to tie the major-league record shared by Frank Schulte, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Rudy York.18 Just to show that he hadn’t changed, he led the league in strikeouts for the sixth time.

On September 7 at Cincinnati, DiMaggio slammed an RBI double in the first inning off 18-year-old Hermie Wehmeier, who was making his major-league debut, then doubled home another run in the second off 46-year-old Hod Lisenbee, pitching the final game of his career. DiMaggio crashed into the center field wall in the eighth, breaking his right elbow and ending his season.

The likes of Wehmeier and Lisenbee vanished from the majors in 1946 when the war veterans came home. Army veteran Johnny Wyrostek took DiMaggio’s job in center field. On May 1 Philadelphia traded the 33-year-old DiMaggio to the Giants, his fifth team. His stay in New York, where Joe had just rejoined the Yankees, lasted barely a month. He went 0-for-25 and was sold to the San Francisco Seals, where he had started 14 years before.

Seals manager Lefty O’Doul achieved the DiMaggio trifecta; Vince’s arrival meant he had managed all three brothers. While Dom played in his only World Series with the Red Sox in 1946 and Joe struggled to recapture his prewar form, Vince was a benchwarmer in Triple A. San Francisco released him after the season.

DiMaggio was working in a sporting goods store the next spring when his old manager Casey Stengel signed him for the PCL Oakland Oaks. He hit over .330 and belted 11 homers in the first two months of the season, but tailed off to a final .241 average. In 1948, he began a new career as a player-manager, first at Stockton in the Class-C California League and then for 2½ years at Class-D Pittsburg, California, until that franchise folded midway through the 1951 season. After finishing the year with Class-B Tucson, he left the game at 38.

For the rest of his life, DiMaggio bounced from one job to another, scuffling to support his wife, Madeline, and daughters Joanne and Vicky. He worked for a time handling purchasing and inventory for the family restaurant, DiMaggio’s Grotto, on Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco. Customers often prevailed upon him to sing, and they didn’t have to ask more than once. He sang operatic arias and popular love songs in a fine tenor voice. Dom thought he had missed his calling by not pursuing an opera career.19

Vince was especially happy driving a milk truck, when he “would start at 4 a.m. delivering milk, butter and eggs to homes, and in the afternoon I would be going after bass in the Sacramento River.”20 Fishing was a pleasure as long as he didn’t have to do it for a living. He finally settled in the Los Angeles area and had stints as a bartender and a liquor salesman.

His life changed in 1971 when he was watching evangelist Billy Graham on TV. “I got up from my chair — I didn’t think I did it on my own — got down on my knees and prayed.” His embrace of born-again Christianity became the guiding principle of his later years. “I used to be a sinner,” he told an interviewer. “I enjoyed drinking, gambling and sex. Most everything — you name it, I did it.” Now, he said, he and Madeline went to church every day.21

While Joe made a comfortable living getting paid for being Joe DiMaggio, Dom prospered in business. He built a multimillion-dollar manufacturing company in the Boston area and became wealthy enough that he twice tried to buy the Red Sox. Vince, who had left the majors a year before the players’ pension plan began, was still working as a Fuller Brush salesman in his 70s. “When Joe got tired of his clothes, he’d send them to my dad,” Joanne said. “Dad would take them to a tailor and get them fitted. Dominic, the same thing.”22

The brothers sometimes went years without speaking more than a few words to each other. “Joe’s always been a loner, and he always will be,” Vince said. “When the folks were alive, we were a lot closer.”23

They got together in uniform for occasional old-timers games. They first played in the same outfield at a 1956 San Francisco Seals reunion organized by Lefty O’Doul. Thirty years later, after Joe and Vince had a falling-out, Dom persuaded both to join him for an old-timers day at Fenway Park. Soon afterward Vince was diagnosed with colon cancer. He died at 74 on October 3, 1986.

“I’ll tell you this, I never felt I played in the shadow of either of them,” he insisted in old age. “Joe was a better batter, but I could play rings around him as far as knowledge of the game and plays in the outfield. I could smoke those throws. If you put a dime on second base, I could hit it from the outfield.

“No club owner ever paid me on the basis of what my last name was.”24

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Edward Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, Vince DiMaggio? (New York: Bantam, 1983), 260.

2 Family history from Tom Clavin, The DiMaggios (New York: HarperCollins, 2013) and Richard Ben Cramer, Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000).

3 David Halberstam, The Teammates (New York: Hyperion, 2003), 123.

4 Ibid.

5 J.G.T. Spink, “‘That’s Our Pop’ — Dominic DiMaggio, Sr.,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1941: 4. The story erroneously identified Giuseppe DiMaggio as Dominic Sr.

6 Burt Whitman, “Vince DiMaggio, Joe’s Brother, to B’s in Deal for Chaplin, Thompson, Cash,” Boston Herald, December 5, 1936: 19.

7 Arthur Sampson, “Bill McKechnie Seeks Whiffer,” Boston Herald, August 13, 1939: 60.

8 Dave Larsen, “A DiMaggio Named Vince … And His Brush With Baseball Fame,” Los Angeles Times, February 27, 1983: VIII-1.

9 The record stood for 54 years, broken by Jason (41) and Jeremy (20) Giambi in 2002.

10 The record stood for 22 years, until Detroit’s Jake Wood registered 141 strikeouts in 1961.

11 “Morning Briefing,” Los Angeles Times, October 6, 1986: III-2.

12 Whitman, “B’s Use Vince DiMaggio as Installment on Miller,” Boston Herald, February 5, 1939: 38.

13 Ernest Mehl, “Vince DiMaggio Is Transformed into a Big Threat of Baseball,” Kansas City Star, May 24, 1939: 21.

14 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, July 29, 1943: 23.

15 Ibid., April 23, 1944: S2.

16 Havey J. Boyle, “Hunger Strike in Reverse Looms in Buc Nosebag Issue,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 11, 1944: 14.

17 Boyle, “Mirrors of Sport,” Post-Gazette, April 2, 1945: 14.

18 Ernie Banks broke the record with five grand slams in 1955. In 2018 the record is six, by Don Mattingly and Travis Hafner.

19 Larsen, “A DiMaggio Named Vince.”

20 Ibid.

21 “Joe DiMaggio’s brother tells how faith helped him conquer booze and gambling,” unidentified clipping in Vince DiMaggio player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

22 Clavin, The DiMaggios, 262-263.

23 Kiersh, Where Have You Gone, 260.

24 Larsen, “A DiMaggio Named Vince.”

Full Name

Vincent Paul DiMaggio

Born

September 6, 1912 at Martinez, CA (USA)

Died

October 3, 1986 at North Hollywood, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.