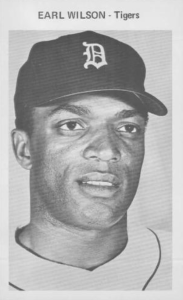

Earl Wilson

Ponchatoula, Louisiana, in the 1930s was a small town that had suffered a number of lumber mills closing in the previous decade. By the 1930s, it was known primarily as a strawberry farming region. It was into this area that on October 2, 1934, Earl Lawrence Wilson was born. He later changed his name to Robert Earl Wilson. The family’s roots were in this area as both, his father, Earl, and mother, Amanda, were from the region. Amanda’s father, in fact, ran a nearby strawberry farm. Earl had been preceded by a sister and eventually would become the middle child upon the birth of another sister. Both his parents were known as hard workers with his father employed as a school custodian and his mother, besides looking after her own household, was employed as a housekeeper.

Ponchatoula, Louisiana, in the 1930s was a small town that had suffered a number of lumber mills closing in the previous decade. By the 1930s, it was known primarily as a strawberry farming region. It was into this area that on October 2, 1934, Earl Lawrence Wilson was born. He later changed his name to Robert Earl Wilson. The family’s roots were in this area as both, his father, Earl, and mother, Amanda, were from the region. Amanda’s father, in fact, ran a nearby strawberry farm. Earl had been preceded by a sister and eventually would become the middle child upon the birth of another sister. Both his parents were known as hard workers with his father employed as a school custodian and his mother, besides looking after her own household, was employed as a housekeeper.

Wilson grew up loving sports. He went to Hammond Colored High School, where he played varsity basketball. His passion, however, was baseball and he played whenever and wherever he could get the chance. He played at Athletic Park in Ponchatoula for as many community teams as he could. As he grew, his parents, according to son Greg, instilled in him a strong work ethic and desire to always strive to be successful. These characteristics would be very important in Earl’s life as it unfolded.

Wilson began playing as an outfielder but soon switched to catching. He was always a strong hitter. In 1953, in what the Baseball Library web site describes as his first real season as a professional, he, because of his strong arm, was changed into a pitcher. He went he went 4–5 with a 3.81 ERA—and more walks (61) than strikeouts (56) for the Bisbee-Douglas Copper Kings of the Arizona-Texas League.

It was during this season that the Boston Red Sox began to notice the young ballplayer. The scouting report sent to the team’s head office is indicative of the racial bias that Wilson had to overcome in his early years as a professional ballplayer. It stated, “He is a well mannered colored boy, not too black, pleasant to talk to, well educated, has a very good appearance and conducts himself as a gentleman.” That year the Red Sox signed Earl; the first African American to play a game for the Bosox, Elijah “Pumpsie” Green, wasn’t signed until 1956. Still, these were the first two African Americans ever signed by Boston. Earl was drafted into the Marines in 1957. Although he continued to play military ball his opportunity to become the first black player to crack the Red Sox lineup was delivered a setback. It looked like Pumpsie Green would get there first

In 1959, Green had hit .400 during spring training with the parent Sox and was named “Camp Rookie of The Year” by the press. Even with those accomplishments, Green had not secured anything. When writers asked owner Tom Yawkey if Green would make the team, he replied, “The Sox will bring up a Negro if he meets our standards.” By the time camp had broken, General Manager Bucky Harris seemed to indicate that Green had made the team—but this was not the case. Reports were that manager Pinky Higgins had gone to Yawkey and had Harris overruled. Boston sportswriter Al Hirshberg later claimed that Higgins had made the following statement, “There will be no niggers on this team as long as I have anything to do with it.”

The demotion of Green caused a furor among civil rights groups. The NAACP called for an investigation into the affair. The Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination held hearings into the matter. Neither Yawkey nor Harris attended. They put the team’s defense into the hands of a young team lawyer by the name of Dick O’Connell. He argued the Red Sox were employing eight black personnel at the time, one at Fenway Park and eight in the minor leagues. The outcome of the hearing resulted in the Red Sox being absolved of any charges of discrimination for the promise of making every effort to end the apparent segregation that existed on the team.

By that July, Green was hitting .325 at Minneapolis and had just been named an American Association All-Star for the second straight year. On July 21, 1959, Green made his debut for Boston to become the first African American to play for the Red Sox. One week later, Robert Earl Wilson, who had a record of 10–2 at the time, made his first appearance.

During the remainder of that season, Wilson appeared in nine games and compiled a modest 1–1 record with a 6.08 ERA. He recorded his first victory in the majors August 20 in an 11–10 win over the Kansas City A’s. Besides picking up his first big-league win, he also showed his bat was a serious weapon as he picked up three RBI in the game.

In the 1960 season, Wilson appeared in 13 games and had a 3–2 record. He lowered his ERA to 4.71 and lowered his walk to strikeout ratio as well. His control at this early stage of his career was always a concern. In spite of what appeared like good progress Wilson would not make a major league start in 1961.

The following season, 1962, saw Wilson come back to stay. It did not take long for him to distinguish himself. On June 26 of that year, he took the mound against the Los Angeles Angels and Bo Belinsky in front of 14,002 fans in Fenway Park. That night he became the first African American to hurl a no-hitter in the American League, pitching the Sox to a 2–0 win. He helped his own cause by hitting a home run, which proved to be the game-winning run. During the contest, Wilson faced 31 Angels hitters. He gave up four base on balls, struck out five, had eight ground-ball outs and 14 fly-ball outs. The Red Sox made several key defensive plays behind Wilson, as happens in most no-hitters. These included a fine catch at the wall by Carl Yastrzemski, a grab of a line drive by shortstop Eddie Bressoud, and a catch of a 400-foot fly ball to center field by Gary Geiger. Following the game, Wilson commented, “Honestly, I didn’t think I had as good as stuff as I had in other games I’ve had this year. I never had any idea anything like this would ever happen to me. The good man was with me tonight.” Owner Yawkey gave Wilson a $1,000 bonus for his achievement, declaring, “I am more excited now than I was during Mel Parnell’s no-hitter as Wilson is just arriving at what could be a brilliant career.”

The victory was Wilson’s sixth of the season. He went on to finish the year with a 12–8 won-lost record with a 3.90 ERA. He pitched 191.1 innings. For the first time his strikeouts outnumbered his walks (137–111). It was also in 1962 that Wilson became one of the first professional athletes to have an agent represent him in contract negotiations. It occurred as a result of a minor accident in which Earl was involved. He was referred to a young lawyer by the name of Bob Woolf. The association of Woolf with Wilson marked the start of Woolf’s career as a sports agent. It worked out well for both parties as besides being involved in contract discussions for Earl, Woolf also achieved several endorsement deals for the player.

Wilson’s next few seasons saw his won-lost record reflect the overall ineptitude of the Red Sox. In 1963, he earned 11 victories and 16 defeats. Still, he lowered his ERA to 3.76. He also threw more than 200 innings for the first time in his career.

The 1964 season saw Wilson compile an 11–12 record with a 4.49 ERA. He once again had more than 200 innings of work. In the 1965 season Earl had 13 wins to lead the Red Sox. He had 14 losses with an ERA of 3.98 and threw 230.2 innings. He gave up 77 walks but struck out 164 opposing hitters. Two of the highlights of that season for Earl occurred in August. On August 16 he hit two home runs but ended up losing the game 5–4 to the Chicago White Sox. On August 25, he struck out 13 Washington Senators in an 8–3 victory.

Early 1966 saw an event occur that had a monumental effect on the rest of Wilson’s life. During spring training, while in Lakeland, Florida—the spring home of Wilson’s next team, the Detroit Tigers—Wilson and a couple of his teammates, Dennis Bennett and Dave Morehead, decided to go to a local bar named the Cloud 9 for a drink after a day at the park. In Bennett’s words he describes what happened that night: “The bartender asked Dave and I what we wanted. He then turned to Earl and said, `We don’t serve niggers in here.’ So we all got up and left the place. Earl was upset at first as he had never been refused service before.”

Author Peter Golenbock, in his book Red Sox Nation, wrote that incidents such as this tended to bring negative publicity to the team rather than to the racist attitudes in the South. Wilson understood this was the case and although he revealed the incident to Boston writer Larry Claflin, he asked that the writer keep it to himself and not write about it. Claflin agreed but another writer found out about it and instead of exposing the racism of the incident focused his story on the Red Sox players going out drinking.

Most observers—including Wilson, according to his son—felt this incident was the reason the Red Sox decided to deal him. To Earl the writing was on the wall when on June 13, the Red Sox acquired two black players, John Wyatt and Jose Tartabull. That night, Earl told his roommate Lenny Green, who was also an African American, “There are too many black players on the team, someone will have to go!” The next morning manager Billy Herman informed Wilson that that he and a black outfielder, Joe Christopher, had been traded to Detroit for veteran outfielder Don Demeter and a player to be named later (a week afterward, Detroit shipped reliever Julio Navarro to the Bosox). Earl at the time had appeared in 15 games with the Sox that season and had a 5–5 record. His ERA was 3.84. Although upset at first, Earl quickly rebounded and went on to post a 13–6 record for the Tigers to finish the year with 18 wins overall and a sparkling Tigers ERA of 2.59. As it turned out, the trade was one-sided in the Tigers’ favor with Demeter retiring at the end of the 1967 season.

For Wilson, though, 1967 was without doubt his finest season. He appeared in 39 games and led the Tigers with 22 wins against just 11 defeats. He also racked up 184 strikeouts. Detroit finished the season just one game behind the “Impossible Dream” Red Sox.

The 1968 season saw the Tigers capture the American League pennant, dominating their opponents. They finished 12 games ahead of their nearest rival, the Baltimore Orioles. Besides Wilson, who finished with a 13–12 record and a 2.85 ERA, Detroit also had Denny McLain win 31 games and Mickey Lolich win 17. Wilson tied his career high with seven home runs during the season. In the World Series, the Tigers came from behind to take the fall classic over St. Louis in seven games. Earl pitched the third game of the Series, going 4.1 innings. He gave up three runs, all earned, on four hits and six walks. He had three strikeouts. The Tigers went on to lose the game 7–3. It was Earl’s only appearance in the Series.

In 1969, Wilson had his last winning season as a pitcher. He finished with a 12–10 record and a 3.31 ERA. He also pitched more than 200 innings for the last time. The Tigers finished the year in second place, 19 games behind the pennant-winning Orioles.

During his final season in Detroit, Earl was involved in one of the most unusual plays ever to occur in baseball. On April 25, 1970, in a game against the Twins, Wilson swung and missed on a pitch for what appeared to be the third out. The umpire believed the catcher had trapped the ball and did not call Wilson out. Not realizing this, the catcher rolled the ball toward the mound and the Twins began to leave the field. Earl started running around the bases and before the Twins recovered he had rounded third. He tried to get back to third but ended up getting tagged out by the left fielder. It probably was the only strikeout ever to be recorded in the scorebook as 7–6–7. The 1970 season was his final one in the majors. When he was sold to the San Diego Padres July 15, his record was 4–6 with an ERA of 4.41. The Padres were a terrible club that season and finished the year with 99 losses. Earl’s record with the Padres was 1–6 with an ERA of 4.85. He was subsequently released by the Padres on January 13, 1971, at which time he promptly retired from baseball.

In 11 seasons in the big leagues, Wilson had a 121–109 (.526) record. His lifetime ERA was 3.69 and he had 1,452 strikeouts, a rate of better than six for every nine innings pitched. He was a dangerous hitter as well. He had 35 home runs in 740 at bats—a ratio of one homer for every 21 at-bat. (a ratio many regulars would covet). Two of his home runs occurred in the role of a pinch-hitter. He was such a good hitter that Tigers broadcaster Ernie Harwell commented in Wilson’s obituary that appeared in the San Diego Union-Tribune that he recalled Wilson pinch-hitting on numerous occasions. Former Tigers catcher Bill Freehan commented in the same story that Earl was a better hitter than some in the regular Tiger lineup.

Upon his retirement, Wilson decided to move back to Detroit for several reasons. Detroit was one of the few areas that he had been where blacks actually owned businesses rather than being employees. He also remembered the summers he had spent picking strawberries on his grandfather’s farm as a reason he did not return to his Louisiana birthplace. In fact, Earl was just more comfortable in Detroit than anywhere else. His greatest success as a major leaguer happened there and the area had a large number of successful middle-class blacks, many of whom were also entrepreneurs. In a book published by the Detroit Free Press titled The Corner: A Century of Memories at Michigan and Trumbull, Wilson made the following comment: “Back home in Louisiana, I had never seen black people who owned businesses. When I came to Detroit, I saw this. They had big homes. Just a lot of things I wasn’t accustomed to. I just fell in love with the Tigers and knew this was the place I wanted to be.”

Moving back to Michigan, Wilson established the Earl Wilson Company, which repaired forklift trucks for the Big Three automakers. He later started Auto Tech Fillings, a company that manufactured a substance that stopped echoes from occurring inside automobiles.

By 1989, Wilson had decided that he once again wanted to be involved in baseball but not in the usual way. He joined the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT) because he had a strong desire to help former major league baseball players and their families who were not as fortunate as he was. After three years in the organization, Earl was elected its vice president, and in 2000 he was elected president, holding the position until 2004. The organization was formed to provide assistance, especially to those who played before salaries or pensions were as generous as they are now. The assistance BAT offers takes many forms including health care, financial grants to those in need, rehabilitative counseling, or whatever is required to attain comfort and dignity for former ballplayers and their families.

According to BAT officials at Major League Baseball headquarters, Wilson was a very active member of the group. Besides holding executive positions, he helped raise financial contributions in a variety of ways, including the Earl Wilson Celebrity Golf Tournament, which ran for five years. Ted Sizemore, the current BAT president in 2007, said, “Earl was one of a kind. As a former ballplayer, he knew how important it was to help one of our own and that’s why he became involved with BAT and excelled in his duties as president and CEO.”

In 2002, as BAT president, Earl returned to Boston to attend the memorial service for Ted Williams. According to Earl’s son Greg, Wilson thought a lot of Teddy Ballgame. One of the few pieces of baseball memorabilia Wilson kept was a Ted Williams autographed baseball.

The world lost Robert Earl Wilson April 23, 2005, to a heart attack at his home in Southfield, Michigan, at age 70. In the words of ESPN announcer and Hall of Famer Joe Morgan, “I appreciated how he cared about former baseball players who were facing tough times. His death was not a loss for just his family but also for all of baseball.”

Sources

Golenbock, Peter. Red Sox Nation. Chicago: Triumph Books. 2004.

Nowlin, Bill. Mr. Red Sox: The Johnny Pesky Story. Cambridge, Mass.: Rounder Books. 2004.

Stout, Glen and Richard Johnson. Red Sox Century. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 2004.

Boston Globe, April 26, 2005.

San Diego Union-Tribune, April 25, 2005.

www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/ballplayers/W/Wils

www.baseballreference.com

www.boston.com/sports/baseball/redsox/articles/2005/04/26

www.fergiejenkinsfoundation.org/13

www.insider.espn.go.com/columns

www.1967alpennant.com/1967-tiger-retrospective-earl-wilson/

www.ponchatoula.com

www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earl_Wilson

www.retrosheet.org

www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20050426/news

Interviews with Greg Lawrence, son of Earl Wilson.

Interviews with the Office of the Baseball Assistance Team, New York.

Note

This article originally appeared in the book Sock It To ‘Em Tigers–The Incredible Story of the 1968 Detroit Tigers, published by Maple Street Press in 2008.

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Earl Lawrence Wilson

Born

October 2, 1934 at Ponchatoula, LA (USA)

Died

April 23, 2005 at Southfield, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.