Denny McLain

On September 19, 1968, at Tiger Stadium, Detroit right-hander Denny McLain was cruising along in the top of the eighth with a 6-1 lead over the New York Yankees. He had won his 30th game five days earlier, and the Tigers had already clinched the American League pennant. When Yankees first baseman Mickey Mantle came to bat with one out and nobody on, McLain let Mantle know that he would give him whatever pitch Mickey wanted. After a few batting-practice fastballs were skeptically ignored or fouled off, Mantle signaled for a fastball letter high, McLain delivered it, and the Mick deposited it into the right-field seats. It was Mantle’s 535th career home run, passing Jimmie Foxx for third place all-time. McLain was coy in the locker room, and later received a stern rebuke from Commissioner William Eckert, but freely admitted the circumstances of the event over the subsequent years.

On September 19, 1968, at Tiger Stadium, Detroit right-hander Denny McLain was cruising along in the top of the eighth with a 6-1 lead over the New York Yankees. He had won his 30th game five days earlier, and the Tigers had already clinched the American League pennant. When Yankees first baseman Mickey Mantle came to bat with one out and nobody on, McLain let Mantle know that he would give him whatever pitch Mickey wanted. After a few batting-practice fastballs were skeptically ignored or fouled off, Mantle signaled for a fastball letter high, McLain delivered it, and the Mick deposited it into the right-field seats. It was Mantle’s 535th career home run, passing Jimmie Foxx for third place all-time. McLain was coy in the locker room, and later received a stern rebuke from Commissioner William Eckert, but freely admitted the circumstances of the event over the subsequent years.

It was classic McLain: charming, cocky, arrogant, reckless. Just 24 years old, and arguably the biggest star in his sport at that moment, McLain had played by his own rules his whole life, and as baseball’s first 30-game winner in 34 years, he was not going to be changing any time soon. He had a prickly relationship with his teammates, managers, the fans, and the city of Detroit, all of which he was apt to criticize at the slightest provocation. Bill Freehan, his catcher, once wrote, “The rules for Denny just don’t seem to be the same as for the rest of us.”1

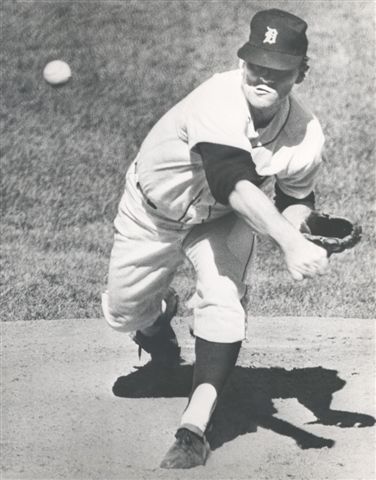

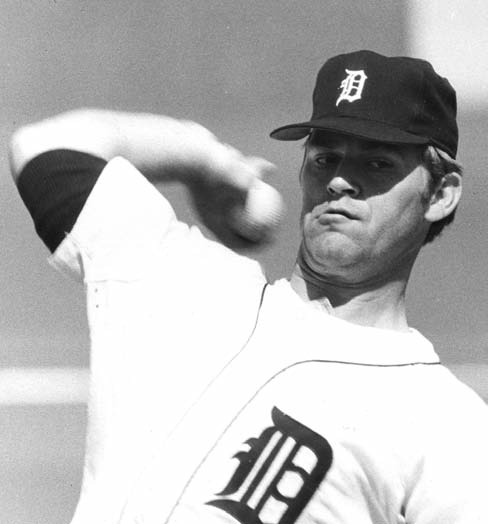

A virtual gunfighter on the mound, McLain pulled his hat brim down so low that he had to tilt his head backward to see the signs from his catcher. He worked fast and without deception, throwing pitch after pitch in the strike zone, even ahead in the count. Although he had a change and an overhand curve, he used fastballs and hard sliders for the most part, challenging the hitter with every pitch, often throwing one letter-high fastball after another. If a batter hit the ball hard, the next time up McLain would just give him the same pitch in the same location. “Here you go,” he seemed to say, “let’s see you hit it again.”

Off the field, McLain’s life was equally carefree and, it would turn out, even more reckless. His idol was Frank Sinatra, not just for the legendary singing voice but because Sinatra exuded wealth and power. “Sinatra doesn’t give a damn about anything, and neither do I,” said Denny.2 Likely due mainly to his pitching prowess, Denny had a successful side career as organist; he played on The Ed Sullivan Show, headlined performances in Las Vegas, and cut a pair of LPs. Not content with traveling like the rest of us, he bought his own airplane, and learned to fly it himself. Time magazine put McLain on its cover in 1968, comparing him to a “high-school wise guy.”3

For his 31 victories and 1.96 ERA, McLain won the American League’s Cy Young and Most Valuable Player awards in 1968, and his team won its first World Series in 23 years. He won the Cy Young again in 1969 (tying with Baltimore’s Mike Cuellar) when he won 24 games. He made nearly $100,000 from the Tigers, and much more than that off the field. He was living the dream life. Until he wasn’t.

Dennis Dale McLain was born on March 29, 1944, in Markham, Illinois, to Tom and Betty McLain, both Irish Catholics. Tom had been a star high-school shortstop in Chicago, but married Betty at age 18 in 1941, and adhered to her demand that he not travel around chasing a baseball career. When Dennis was born, Tom was in the Army in Europe; he later held jobs as a truck driver and insurance adviser, and made extra money giving electric-organ lessons.

Denny remembered Tom as a hard worker who chain-smoked and guzzled beer. Denny and his brother Tom lived in fear of their father’s angry outbursts, which often resulted in beatings. Tom also got in frequent fistfights, on at least one occasion responding to the heckler at one of his son’s Little League games. Denny did not try very hard to avoid his father’s wrath, though – once, at age 12, taking the family car for a joyride. This behavior became more and more typical. Denny’s memories of his mother are no better; he remained bitter over her failures to intervene on her children’s behalf, and he has depicted Betty as a cold and heartless woman.

Tom encouraged Denny’s baseball career, organizing the first youth baseball league in their hometown of Markham when Denny was 7, and a few years later driving his son to a neighboring town to play in a Babe Ruth baseball league. Denny dominated these leagues as a pitcher, just rearing back and throwing one fastball after another. Tom died suddenly of a heart attack at age 36 when Denny was a 15-year-old high school freshman. Betty quickly remarried, and Denny began doing whatever he pleased.

McLain attended Catholic schools, first at Ascension Grade School, then receiving a baseball scholarship to attend Chicago’s Mount Carmel High School. An indifferent student who had trouble keeping quiet, Denny led his team to three city championships, amassing a 38-7 record on the mound. Upon his graduation in June 1962, McLain signed with the White Sox, receiving a $10,000 bonus, and another $7,000 if he made it to the major leagues. Days later he reported to Harlan, Kentucky, to play for the Smokies in the Class D Appalachian League.

McLain had a spectacular professional debut on June 28 against the Salem Rebels, tossing a no-hitter and striking out 16. He lost his second start, but allowed no earned runs and struck out 16 more batters. Though he was in Harlan only a couple of weeks, that was sufficient time for McLain to exhibit the reckless behavior that would become his trademark, defying team rules by making a 30-hour round trip to visit his girlfriend in Chicago on an off day. He figured, correctly, it would turn out, that throwing a no-hitter would entitle him to more leeway than other players. This notion had been applied growing up in Chicago, and would stay with him all the way to the major leagues. After just two games, with a 0.00 ERA and 32 strikeouts, McLain was deemed to have mastered the Appalachian League, and was promoted to the Clinton, Iowa, C-Sox in the Class D Midwest League.

The Midwest hitters weren’t as overmatched by a pitcher who threw almost all fastballs, and Denny had to settle for a 4-7 record, but with 93 strikeouts in 91 innings. In Clinton he went AWOL on the team several times, costing himself several hundred dollars. On the mound, his promise was still apparent.

That offseason McLain began dating Sharon Boudreau, daughter of former star shortstop Lou Boudreau, then an announcer for the Chicago Cubs. The two had met in high school, but their relationship escalated enough that they were engaged by January 1963, and married the following offseason.

At the time, players with one year of service in the minor leagues were susceptible to a draft if not promoted to the major leagues. The White Sox were faced with this dilemma with McLain, along with fellow pitchers Bruce Howard and Dave DeBusschere. In the end, the White Sox chose to protect the other pitchers and not McLain, the local boy. The Detroit Tigers soon claimed McLain.

McLain did not take long to soar through the Detroit system. He began the 1963 season in the Class A Northern League with Duluth-Superior, and after 18 starts he was 13-2 with a 2.55 ERA, with 157 strikeouts in 141 innings. He then moved on to Knoxville in the Double-A Sally League, and finished 5-4 in 11 starts. In September he was in the major leagues.

McLain’s major-league debut was almost as spectacular as his pro debut in Harlan. Taking the hill against the White Sox in Tiger Stadium on September 21, he came away with a 4-3 complete-game seven-hitter, starting the Tigers’ scoring by belting a home run off Fritz Ackley in the fifth inning. This would be the only home run of his major-league career.

McLain began the 1964 season with Syracuse in the Triple-A International League, but he did not stay long. After fashioning a 3-1 record and a 1.53 ERA in eight starts, he was promoted to the Tigers in early June. Just 20 years old, Denny joined the rotation for the rest of the season, winning four of nine decisions for the fourth-place Tigers.

McLain later claimed he turned the corner as a pitcher in the winter of 1964-1965 when he pitched for Mayaguez in the Puerto Rican Winter League, finishing 13-2 to help his team to the championship. Back in the States, Denny’s first full season resulted in a 16-6 record and a 2.61 ERA. McLain relied essentially on one pitch-a letter-high fastball with movement, a pitch that was a strike in the 1960s but would not be a generation later. Tigers manager Charlie Dressen advised McLain to just throw strikes, and said he’d get a lot of hitters out with his stuff. He struck out 192 in 220 innings, including a league-record seven in a row in a relief appearance on June 15.

His success continued in 1966. Starting the season 13-4, he was selected to start the All-Star Game in St. Louis and responded by retiring all nine National League hitters he faced. He did not pitch well after the break, but finished 20-14 with a 3.92 ERA, with 192 strikeouts. Dressen, whom McLain has always credited for his breakthrough, had to leave the team after suffering an early-season heart attack, and died soon thereafter. Denny would never find another manager to his liking.

McLain’s outsized personality, combined with his pitching success, began to earn him a lot of money off the field. He played the organ, either by himself or with a group, in clubs around the Midwest, and earned a $25,000 endorsement deal with Hammond organs. McLain’s biggest personal vice was his huge appetite for Pepsi-Cola, on the order of 24 bottles every day. When the company heard of his obsession, they signed him as a sponsor, paying him $15,000 a year, plus 10 cases (240 bottles) delivered to his house every week. By the age of 22, McLain was earning more money off the field than he was from the Tigers.

Detroit lost a heartbreaking four-team pennant race in 1967, due in large part to an off year from McLain. He finished 17-16 with a 3.79 ERA, and was winless after August 29. After several poorly pitched games — no wins, two losses, 13 runs in 13⅔ innings in four starts — on September 18 McLain reported that he had severely injured two toes on his left foot. His foot had fallen asleep while he was watching television, he said, and he stubbed it getting up when he heard some raccoons that were getting into his garbage cans. In the heat of the pennant race, McLain did not pitch again for 13 days, until the very last game of the season. (If Detroit had won, the club would have forced a one-game playoff with the Red Sox for the American League pennant.) McLain was again ineffective, and the Tigers lost to the California Angels to fall one game short. His teammates were not happy about McLain’s efforts that season, and many doubted his injury story.

Entering the 1968 season, the Tigers were considered a talented group of individuals who could not play together. They proceeded to debunk that theory by leading the league nearly wire to wire on the way to a 103-win season and an impressive 12-game margin over the second-place Orioles. The star of the team, and of all of baseball, was Dennis Dale McLain, who captured the attention of the sports world with his 31-6 record. No pitcher had won 30 games since Dizzy Dean in 1934, and by midsummer McLain’s pursuit drew attention across the country. The 30th win came on September 14 on national television against the Oakland Athletics, a 5-4 victory. His 31st came five days later, the game in which he grooved the pitch to Mantle. In the Tigers’ World Series triumph over the St. Louis Cardinals, McLain lost twice to Bob Gibson to help put the Tigers in a 3-1 hole, but won Game Six as the team pulled out the Series. Mickey Lolich won three times to lead the Tigers.

Entering the 1968 season, the Tigers were considered a talented group of individuals who could not play together. They proceeded to debunk that theory by leading the league nearly wire to wire on the way to a 103-win season and an impressive 12-game margin over the second-place Orioles. The star of the team, and of all of baseball, was Dennis Dale McLain, who captured the attention of the sports world with his 31-6 record. No pitcher had won 30 games since Dizzy Dean in 1934, and by midsummer McLain’s pursuit drew attention across the country. The 30th win came on September 14 on national television against the Oakland Athletics, a 5-4 victory. His 31st came five days later, the game in which he grooved the pitch to Mantle. In the Tigers’ World Series triumph over the St. Louis Cardinals, McLain lost twice to Bob Gibson to help put the Tigers in a 3-1 hole, but won Game Six as the team pulled out the Series. Mickey Lolich won three times to lead the Tigers.

After the season, McLain won the American League Cy Young and Most Valuable Player awards, among many other honors. He spent the offseason flying around the country playing the organ, making money, and running his mouth. When asked during a performance in Las Vegas about teammate Mickey Lolich, who had saved the Tigers’ season with his performance in the World Series, McLain responded: “I wouldn’t trade (one) Bob Gibson for 12 Mickey Loliches.”4

McLain had another big year in 1969, winning 24 games and capturing a second consecutive Cy Young Award (tying with Baltimore’s Mike Cuellar). The best pitcher in the game, the 25-year-old McLain was also raking in money on endorsements, appearing on national talk shows, and performing as a headliner in Las Vegas. As the 1960s ended, Denny McLain had reached a level of fame that very few baseball players have ever reached. When considering his outside income along with his baseball salary, he made more money than anyone in the game, and he spent it as fast as it came in.

The good times ended very suddenly.

In February 1970 Sports Illustrated featured McLain on its cover next to the headline “Denny McLain and the Mob, Baseball’s Big Scandal.”5 The mob? According to the magazine, in early 1967 McLain invested in a bookmaking operation based in a restaurant in Flint, Michigan; several of his partners were part of the Syrian mob. When a gambler named Edward Voshen won $46,000 on a horse race, his bookie couldn’t pay it off, suggesting instead that Voshen find the bookie’s partners. One of his partners was McLain. Voshen spent several months trying to get his money, finally enlisting the aid of mobster Tony Giacalone. According to the magazine’s sources, Giacalone met with McLain in early September and, while threatening much worse, brought his heel down on McLain’s toes and dislocated them. This would have coincided with time of McLain’s ankle-toes injury in September 1967. The magazine also reported that Giacalone had bet heavily on the Red Sox and Twins to win the pennant, and had made a large bet on the Angels in McLain’s final start.

McLain denied most of the story. He admitted to investing in the bookmaking business to the tune of $15,000, but claimed that his partners reneged on him, causing McLain to withdraw his support. He told Bowie Kuhn, baseball’s commissioner, that he was completely uninvolved in the ring at the time of the Voshen bet, but oddly admitted that he had loaned $10,000 to one of the partners to help pay off the debt. Furthermore, he had never met Giacalone, and McLain retold the story of his toe injury. (In subsequent years, McLain recalled that it was an ankle sprain, not injured toes.) Just prior to spring training, Kuhn suspended McLain indefinitely while he conducted an investigation.

The problem with all of these accusations was that many of the people making them were criminals and lowlifes, as Sports Illustrated acknowledged. Although he has continued to deny the allegations regarding his injury, his denials have been in themselves damning. In his 2007 memoir I Told You I Wasn’t Perfect, he wrote that he was heavily distracted in September 1967. “I was spooked about the ghost of Ed Voshen and worried about being exposed,” he wrote. “I kept expecting someone to tap me on the shoulder and say, ‘Hey, where’s my money?’ or that my car was going to blow up.”6 This fear is precisely why baseball has a paranoia about gambling.

If these problems were not enough, McLain was also suddenly broke. Though his annual income was close to $200,000, McLain had entrusted it all with a lawyer, who either mishandled it or stole it before fleeing to Japan. Without his baseball income, McLain’s financial problems caused him to file for bankruptcy. Claiming that all of his problems were due to poor business decisions, his petition listed debts of $446,069 and assets of only $413.7

On April 1, 1970, Kuhn announced his decision. He continued McLain’s suspension until July 1, roughly half of the season. Kuhn’s report, among other things, said: “While McLain believed he had become a partner in this operation and has so admitted to me … it would appear that he was the victim of a confidence scheme. I would thus conclude that McLain was never a partner and had no proprietary interest in the bookmaking operation.”8 Kuhn also absolved McLain from any charges that his actions had any effect on baseball games or the 1967 pennant race. (On the contrary, McLain’s later recollection that he feared for his life in September 1967 suggests that the pennant race was quite affected.)

After Kuhn read his statement, a reporter asked him to explain the difference between McLain attempting to become a bookmaker and actually becoming one. “I think you have to consider the difference is the same as between murder and attempted murder,” responded the wise commissioner.9 Reporters all over the country, and especially in Detroit, thought the decision was a whitewash. Denny’s teammates seemed surprised as well. Dick McAuliffe spoke for many when he said: “If Denny’s innocent, it should be nothing. If he’s guilty, then this is not enough.”10 Jim Price, the Tigers’ player representative, said that most Tigers thought McLain would get one or two years, or else nothing at all. Nonetheless, three months it was.

McLain returned on July 1 to a packed house but struggled that night and for the next several weeks. On August 28, in what he claimed was a harmless prank, he doused two Detroit writers with buckets of ice water, earning a seven-day suspension from the Tigers. Before the week was up, Kuhn discovered that McLain had carried a gun on a team flight in August, so Denny was declared through for the season. His 1970 record was 3-5 with a 4.63 ERA.

McLain had lived the past several years by his own rules, and his stunning success on the pitcher’s mound allowed him tremendous leeway. He showed up late, flew his plane to music gigs after games, and popped off about teammates, management, the fans, the ballpark, or the city. When you win 31 games, all of this is forgivable. When you finish 3-5, you are a pain in the neck.

A few days after the 1970 season, McLain was traded to the Washington Senators in an eight-player deal. Although he was just 26 years old — and was just six months removed from being considered one of the best players in the game — the Tigers considered themselves fortunate to acquire pitchers Joe Coleman and Jim Hannan and infielders Aurelio Rodríguez and Eddie Brinkman. They were fortunate indeed.

In his one year in Washington, McLain carried on a yearlong battle with manager Ted Williams, and finished 10-22. He spent 1972 with the Oakland A’s, the Birmingham Barons, and the Atlanta Braves, getting hammered at all three stops, before finally drawing his release by the Braves the next spring. He spent a few weeks with Shreveport and Des Moines in 1973, but the magic was long gone.

His baseball career was over, at age 29, four years removed from winning 55 games over a two-year period. How could this have happened? McLain claims to have suddenly lost his fastball in 1970, but one couldn’t help but notice that he was putting on ten pounds of fat a year. At the time of his release, he was 29 and looked 45. Denny McLain had a remarkable right arm, but he did not seem willing to do the work necessary to stay in the game. He had time to fly around the country playing the organ, but he didn’t have the time to stay in shape. The case of Pepsi he still drank every day likely did not help his waistline.

Without his baseball career to get in the way, McLain could now devote all his energies to his “successful” business ventures. Always looking for the fast buck, he invested in a big-screen-television business, ran a bar, wrote a book, opened a line of walk-in medical clinics. In the mid-1970s he was the general manager of the minor league Memphis Blues, who soon went belly up. McLain filed for bankruptcy again in 1977. His wife, Sharon, left him several times, but he always managed to get her back.

Denny made a living for a while hustling on the golf course. While involved with a financial services company in Tampa, he turned to loan sharking and bookmaking. With losses piling up, he and his colleagues got more adventurous. He once made $160,000 smuggling a fugitive out of the country in his airplane.

Eventually, the US Justice Department began to sniff around Denny’s associates, several of whom were willing to talk. In March 1984 McLain was indicted on charges of racketeering, extortion, and cocaine trafficking. McLain was tried, convicted, and sentenced to 23 years in prison. Thirty months later, an appeals court threw out the verdict on procedural grounds, setting McLain free, and the government ultimately decided to not retry the case.

McLain spent the next several years putting his life back together. He wrote another book, appeared at card shows, worked for a minor-league hockey team, and got his own radio show. He was doing what he could have done all along — making a living being Denny McLain. It was a good living, reportedly making him $400,000 a year.

It wasn’t enough. In 1993 McLain and a friend bought Peet Packing, a struggling 100-year-old meatpacking firm in Chesaning, Michigan. Within a month after the sale, $3 million was taken from the company’s pension fund, and by 1995 the company was bankrupt. Though he denied knowledge of the financial illegalities, McLain and his partner were eventually convicted on charges of embezzlement, money laundering, mail fraud, and conspiracy. McLain spent seven more years in prison.

Released in 2003, McLain made appearances and lived a life as a former baseball hero. His wife, Sharon, divorced him when he returned to prison, but they remarried when he got out. They raised four children: Kristen, Denny Jr., Tim, and Michelle. Kristen McLain was killed in an automobile accident in 1992 at age 26, a tragedy that McLain says caused his downward spiral that led to the debacle with Peet Packing. He continued to battle weight problems. When Sharon was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, Denny decided he needed to get healthier to help take care of her. He underwent bariatric surgery and lost 156 pounds — 24 pants sizes. “I’m trying to get to my playing weight [about 200 pounds],” said McLain. “I would just love one more time to go out to Tigers Stadium and throw one pitch and kick my leg up … and see what would happen.”11

McLain was a great pitcher for a few years before his shocking downfall. He lived by his own rules, and hurt countless people along the way, including teammates, friends, and his own family. But for many people in Detroit, he remained a hero for what he did on the mound for their beloved Tigers.

Last revised: July 1, 2015

An updated version of this article appeared in “Mustaches and Mayhem: Charlie O’s Three Time Champions: The Oakland Athletics: 1972-74″ (SABR, 2015), edited by Chip Greene. It originally appeared in “Sock It To ‘Em Tigers: The Incredible Story of the 1968 Detroit Tigers” (Maple Street Press, 2008), edited by Mark Pattison and David Raglin.

Notes

1 Bill Freehan with Steve Gelman and Dick Schaap, Behind the Mask (New York: World. 1970), 64.

2 David Wolf, “Tiger on the Keys and on the Mound,” Life, September 13, 1968, 82.

3 “Tiger Untamed,” Time, September 13, 1968, 76.

4 David Stevens, “Denny’s Vegas Debut Called ‘Less Than Smashing,’” The Sporting News, November 2, 1968.

5 Morton P. Sharnik, “Downfall of a Hero,” Sports Illustrated, February 23, 1970.

6 Denny McLain with Eli Zaret, I Told You I Wasn’t Perfect (Triumph: 2007), 73.

7 Jerome Holtzman, “Players, Umpires, Books, Law Suits …,” Official Baseball Guide 1970 (St. Louis: The Sporting News), 1970, 263.

8 Holtzman, “Players, Umpires,” 265.

9 Holtzman, “Players, Umpires,” 266.

10 Holtzman, “Players, Umpires,” 266.

11 “Ex-Detroit Tigers pitcher Denny McLain: I’ve lost over 150 pounds,” Detroit Free Press, February 27, 2014.

Full Name

Dennis Dale McLain

Born

March 29, 1944 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.