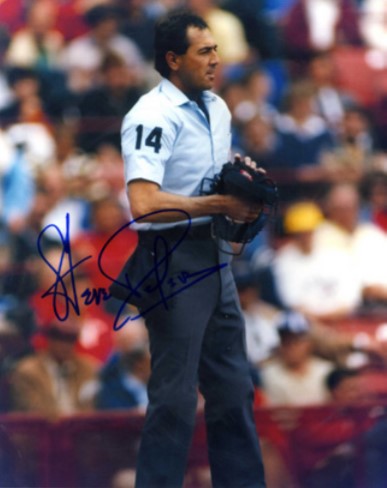

Steve Palermo

Steve Palermo thought about becoming a French interpreter at the United Nations. But he got into umpiring instead, paid $2 per game in his first professional job as a baseball umpire at age 13.

Steve Palermo thought about becoming a French interpreter at the United Nations. But he got into umpiring instead, paid $2 per game in his first professional job as a baseball umpire at age 13.

Oxford, Massachusetts was a small town of around 11,000 people, not that far from Worcester, where Palermo had been born on October 9, 1949. He spent his first nine years in Worcester, but his father was principal of an elementary school in Oxford and when the town mandated that principals were residents of the town, the family made the move and Steve became a third-grade student in the school where his father was principal. Steve’s mother was a “professional homemaker…the consummate housewife and mother. She’s done this job 24/7 and she’s 90 years old and she’s still doing it.”1 It was indeed a fulltime job; Steve had two sisters and three brothers. Sisters Linda and Ann, and brother Jim, became teachers. Brothers Michael and Jim became investment bankers. Linda was first born, Steve was the oldest boy.

Steve himself expected to become a teacher, majoring in education with a minor in French. His freshman year was at Norwich University, transferred to Leicester Junior College, and then to Worcester State. He was a year and a few credits from graduating when he decided he wanted to go to umpire school.

Both Palermo parents promoted the kids going into athletics. Linda was a very good athlete, and played both basketball and softball. Steve played Little League, Babe Ruth League, high-school ball, American Legion, and even some baseball and basketball at Norwich. It was basketball that interested him most there. At baseball, he started out at shortstop, and some second base, though at one time or another played every position on the field. The Little League program in Oxford was a successful one, playing in state finals for a shot at going to Williamsport.

How did he get his first paid job umpiring? “I elevated to the Babe Ruth League when I was 13 years old but my brother was still playing Little League, so I still had some fascination with that. Somebody said, ‘Why don’t you start to try umpiring, Steve? It’s two dollars a game.’ It was a way of making a little bit of pocket money. Monday through Saturdays. Stan Johnson, who was the administrator for District 5 Little League, was very instrumental in making sure that the Little League ran and that it ran well. He made sure the kids had rides to the ballpark so they could make their practices. He was a great promoter of Little League Baseball, to try and help the kids.”

After he was old enough, Palermo started working construction at age 16, for the next four years, “building bridges and roads here in Massachusetts. I put money away because I was going to college. We had a rather large family. My dad, being a principal, there wasn’t a ton of money coming in. We weren’t poor, but by no means were we wealthy.” For the next four years, he worked construction while going to school and over the summers, until a day when Stan Johnson called him and said he was in a bind and needed someone to work home plate at a Little League all-star game.

It was quite an active game with some unusual plays at the plate. Watching the game, by happenstance after his nephew urged him to go to the game, was Barney Deary, administrator of Baseball Umpire Development, and he was in the area looking over a couple of umpires. Deary gave his card to Palermo. The card sat on Palermo’s dressed for a year until August 1971 when he suddenly decided to go to umpire school in February, even at the expense of not completing college. His parents were not at all pleased, but figured he’d get it out of his system and finish his schooling. “Five years later, my first game’s at Fenway Park and my mom and dad are sitting three rows behind home plate. My mom turned to my dad and said, ‘You know, this isn’t that bad a job, really.’”

First, though, there was umpire school and years in the minor leagues.

Umpire school was a six or seven-week program in St. Petersburg. It was a relatively new program, just started a couple of years earlier.2 His first assignment was to work spring training games, based at the Cincinnati Reds camp in Tampa. His class was a productive one – “I believe this class of 1972 had more students who became major-league umpires than any other umpire class to date. That is what I have been told: Eddie Montague, Durwood Merrill, Mike Reilly, Al Clark, and Steve Palermo.”

Palermo said that the most influential men at umpire school were Frank Pulli, Rich Garcia, John McSherry, Larry Napp, Barney Deary, and Joe Linsalata.3

After spring training, he worked for a couple of months in a Spring rookie league in Florida and then was assigned to the New York-Penn League starting in June. He worked the season, then went to the Florida Instructional League in mid-September for a couple of months. “It was a great learning experience in the instructional league and every day we had a supervisor there that we’d talk baseball with for an hour, hour and a half after the ballgame. He resided at the same place we did so we’d all congregate in either his room or some room and everybody would talk about the plays that they had in their particular games that day. We all learned from that. It was very advanced training and I was very fortunate to be able to do that.”

He started 1973 working in the Carolina League, “a very, very tough league…a very advanced A-ball league at the time. I worked a half a year there and there just happened to be an opening in the Eastern League and I got promoted to the Eastern League in mid-1973. I worked there for a year and a half. After that, I got assigned to the American Association.”

Palermo worked the A.A. for the 1975 and 1976 seasons and the beginning of 1977. In October 1975, he married Andrea Lee Giannotta, a flight attendant for United he had met while working winter ball that January. The marriage lasted eight years.

In 1976, he’d worked the Triple-A playoffs and a little while after his postseason was done, he got a call asking him if he could come to Boston. He’d worked with Nestor Chylak, the Hall of Fame umpire, in spring training both in ’75 and ’76. “He was a mentor to me. He was a very demanding taskmaster. You just thought he was tough, but you come to realize later on that it was tough love. He was tough on me for my benefit although I thought he was doing it just because he could yell at me and scream at me about everything. He was one of the biggest influences on my umpiring career. He approached Mr. Butler – Dick Butler, who was the supervisor of umpires in the American League – in 1976, and said, ‘Stevie’s home. He’s worked his playoffs in Triple-A and he’s got time. Would you allow him to come up and work with my crew the last couple of days with Baltimore and Boston at the end of the season? There’s a good chance he’ll be here in ’77, so let’s let him get some dirt on his shoes.’”

Butler called Palermo and asked him if he could come to Boston. “I had no idea or inkling. ‘How’d you like to go up to Boston for a couple of days?’ ‘You want me to come up and sit with you, kind of just visit?’

“He said, ‘No, you won’t be sitting. You’ll be standing the entire game.’ I said, ‘Really?’ I’m thinking, is it so crowded we’re just going to have standing room only? He said, ‘No, you’re going to be standing at third and second base.’ I said, ‘REALLY?’ I said, ‘Yes, sir!’ And so I just packed everything up and I got to Boston way before they needed me.”

Both leagues had been interested in him – they were not yet united in Major League Baseball –but the American League had acted quicker and bought his option.

Chylak sat out the October 2, 1976 game and sat in the stands grading the umpires – Jim Evans at home plate, Greg Kosc at first, Joe Brinkman at second, and Palermo at third. It was a 1-0 game, Reggie Cleveland and two relievers each getting one out for the Red Sox over Dennis Martinez of the Baltimore Orioles. Chylak worked the plate the next day, and Palermo worked second base. The game went 15 innings, a 3-2 Red Sox win.

Palermo was signed to a league contract starting in 1977 – “the first game I ever worked under contract, they wouldn’t let me open in this country; I had to go to Toronto.” It was the first game the Blue Jays ever played in the major leagues, a 9—5 win over the White Sox.

It had been fast advancement to the major leagues. Most first-year umpires at the time were in their early 30s. “Here I was a baby-faced 26-year-old kid and I’m up in the big leagues. It just didn’t happen all that often. I was very fortunate, to have very good instructors and very good instruction. It’s not a political thing. You are out there. You are exposed. You have to be very productive and you have to be very good at what you do…The only way you get to the big leagues is you earn it…You either do the job or the job won’t be there for you to do.”

It helped that Chylak, a senior umpire with 24 years in the big leagues and one who had basically been self-taught, liked his work. Palermo was eager to learn. “I have cocktail napkins – after games – after games, we’d go have a beer or grab something to eat and I used to stuff all these cocktail napkins in my pockets. He’d grab another napkin and diagram where I should be on a particular play when a throw comes in from right field versus center field versus left field. He’d draw a circle around a base and say, ‘Never get inside the circle. You always stay outside the circle. This way you have a wider perspective of the play and the play won’t explode on you.’ All these great little catch phrases and advice that he gave me, I followed to the letter. All it was going to do was enhance my umpiring and make me better. That’s what he was all about. He was all about teaching you things. You’d learn great life lessons with him, and great umpiring lessons with him.”

Life in the majors was a quantum step up from working the minor leagues – new cities, meeting people who knew the crew he was assigned to – Chylak, Richie Garcia, and Joe Brinkman. “There really are three teams out there on the field. There’s that home team, the visiting team, and the third team is that crew of umpires.

“And they work as a team. Being familiar with everybody and their personalities and what they’re going to do on the field. When a ball is hit, in a certain situation, depending on how many runners are on, you know exactly what your responsibilities are, your crewmate knows what responsibilities are his. Everybody knows what to do, and so you know you have to operate like a team and be very well-coordinated in order to be able to cover any and all plays that could possibly happen.”

As of 2014, Palermo works as Major League Supervisor of Umpires. The philosophy regarding an umpire crew remains the same as when he broke in.

“The way we have it set up, we hope the same crew will stay together. Because of the Collective Bargaining Agreement, umpires are granted this time off now and after X amount of days on the road…. Mark Wegner should be on this crew right now, but his vacation slot is now and that’s why Tom Woodring is in here. He’s filling in. Mike Winters was off last week and so Tom was also working for Mike last week, so he just remained with this crew from last week to this week. We like to keep guys on a crew for as long a period of time as we can, with guys’ vacations, because we want everybody to be familiar with each other instead of shuttling guys in and out.”

The core of the crew might be together the whole season, with one person coming and going now and again. And then, beginning with the 2014 season, that same crew will rotate in to New York as a group to work on replay. “Yes, they’ll go into New York a week at a time and all four guys will go in as a crew, and there will also be another crew of four guys in there. There are time slots when they are to report in to the Command Center – I call it the ROC. It’s the Replay Operations Center. It’s in Chelsea.”

After getting that little bit of dirt on his shoes at the end of 1976, Palermo worked as a major-league umpire from 1977 into 1991, when a very unfortunate incident ended his time on the field. Naturally, he had the opportunity to work some key games, including the 1978 single-game playoff to determine the winner of the American League pennant, one ALDS and three ALCS, Dave Righetti‘s no-hitter, the 1983 World Series, and the 1986 All-Star Game.

The 1978 playoff was between the Red Sox and the Yankees at Fenway Park, the so-called “Bucky Dent game,” named after the Yankees shortstop whose wholly unexpected three-run homer in the top of the seventh carried the day. Palermo was the third-base umpire and thus the one who called the ball fair and signaled it was a home run.

Palermo’s father was still working as school principal. “I called my dad up over that weekend and told him that if there was a playoff game, I’d be coming into Boston Sunday night and do you want to come to the game that afternoon? It was a Monday afternoon. I think it was a 2:30 start. He played hooky from school that day. He and I went to the umpires’ room and I grabbed a sandwich and he had a Coke, and he was like a kid in a candy store. He just sat there and listened to everybody as we talked. After the game, he came back up. We used to dress above the Red Sox clubhouse. He knows never to mention anything about the game or what we do. It was just small talk. He just sat there quiet. We all showered and everybody wished everybody well for the offseason. Guys were talking about we got golf games tomorrow, 9 o’clock. Everybody’s excited to get home and get to their families and everything. I jumped in the car with my dad – my mom sat in the back and we got on Storrow Drive and then got on the Mass Pike to get out to Oxford. For the first 15 minutes, I’m playing this game over in my head and trying to wrap my head around its historical meaning in all of baseball. I don’t know whether my mom and dad were talking together or not, because I was just…

“Finally I turned to my dad and then it just popped out of my head, ‘That was a hell of a game, wasn’t it?’ He turned to me and said, ‘You couldn’t have called that ball foul?’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘Bucky’s home run. You couldn’t have called that foul?’ I said, ‘Pop, that ball was 15 feet to the right of the foul pole!’ He said, ‘So what? You’re in Boston. Nobody would have said a word.’ Well…there are some far-reaching circumstances that reach far beyond Boston. I said, ‘Pop, I’d be looking for a recommendation from you because I wouldn’t be doing this very much longer if I did that.’ When I talk to people, I say, ‘You have no idea what internal pressure is, until your parents might be rooting for a team.’

“It’s funny. I walk off a field and we’ll go to a restaurant and know somebody there who’ll ask, ‘What was the score of the game?’ and I’ll say, ‘I don’t know. I think it was 5-4, but I don’t know who won.’ You don’t care who wins or loses. You just make sure that you keep that playing field level all the time.”

Truly? He worked the whole game and didn’t really know who won or lost? “Yeah. If you stop and think for a second. Come August, you’ve been to all these different towns and sometimes you wake up in a hotel…these Hyatt rooms all look the same or these Marriott rooms all look the same, and you’ll call the hotel operator and say, ‘Can you tell me what town this is?’ She’ll say, ‘Yes, sir. You’re in Chicago, Illinois.’ ‘OK, thank you. Good night.’ It happens. You wake up and you go, ‘Where am I today? Is this Chicago or are we in Milwaukee?’ That isn’t the importance of your job.”

The importance of the job is to make the calls correctly and tunnel focus can be key in doing so. Umpires don’t care about how the official scorer may rule on certain plays. The difference isn’t taught in umpire school. “We don’t want to know if it’s a base hit or an error. We don’t know if that run is scored as an earned run or an unearned run. If you asked an umpire, ‘How would you rule that?’ – they probably don’t know how to score a game, because it is not taught to them. They don’t want to learn it, and the people who teach don’t want that to be an influence on an umpire’s decision…All the subtleties of official scoring, I have no idea. And even now, even though I am not on the field umpiring, I still don’t, because I want to look at the game as objectively as possible.” Official scorers, of course, can change their determination after the game, the next day, or even later. Umpires don’t have that leeway.

Working another Red Sox/Yankees game, on the Fourth of July 1983, Palermo was the home-plate umpire – and perhaps the only one at Yankee Stadium who didn’t know until the ninth inning that Dave Righetti was pitching a no-hitter. He was focused on calling the balls and strikes correctly, and in position and ready to make any other call he might need to.

There was one call in that game he should have made, but could not. It was 94 degrees and a pretty close game, 2-0 in favor of the Yankees after 7 ½ innings. Righetti hadn’t given up a hit. With the Yankees batting in the bottom of the eighth, Lou Piniella hit a foul popup over by the seats on the first-base side. Just as Boston catcher Jeff Newman started to reach into the stands, Palermo blew out his knee. “It felt like somebody took a boat oar and just knocked my left knee out from underneath me and I went flying toward the crash pad.” First-base umpire Rick Reed was in position to make the call. Though the injury cost Palermo six weeks after surgery, the severity was not so certain at the time and he finished the game.

After eight full, with only three outs standing between Righetti and a no-hitter, the 41,077 at Yankee Stadium gave the Yankees pitcher a standing ovation as he walked out to the mound. Palermo thought, “That’s nice. They’re giving him a nice round of applause. The kid didn’t get selected to the All-Star Game and these people are kind of sending him off after the first half of the season with good thoughts.” As Righetti was taking his warmup pitches, Palermo glanced up at the scoreboard and saw no runs, no hits, and one Red Sox error. He thought maybe the scoreboard was broken and told Yankees catcher Butch Wynegar that he wanted to talk to him after the game. Wynegar said, “Steve, I might be jumping up and down when this game’s over. Whatever you’ve gotta ask me, ask me now.” Palermo thought to himself, heck, he didn’t believe in superstition and so said, “I didn’t know this guy had a no-hitter going.” Wynegar was taken aback and laughed, “That’s what makes you the wizard. You just stay right in the moment.”4 Palermo was so focused on one play at a time, he hadn’t realized there was a no-hitter in progress.

He still remembers the final at-bat. On a 1-2 count –one strike away – “Righetti threw a pitch on the outside part of the plate, that was just off the plate, outside down and away, and I called it a ball and everybody at Yankee Stadium booed like hell. I thought they were going to come over the wall after me. I remember that pitch.”5 There was no debate about strike three; Wade Boggs swung and missed. Palermo never said, “Strike three!” He says he just turned and walked away, and headed to the umpires’ room. “Jerry Neudecker had worked Catfish Hunter’s perfect game so he knew what it was like to work a no-hitter. He said, ‘They aren’t easy, are they, Kid?’ I said, ‘No, they’re not.’ Then I said, ‘I’m glad I didn’t know it until the ninth inning.’ He said, ‘What????’ I told him.”

His first postseason was in 1980, when the Royals swept the Yankees in the ALCS. It was his fourth year. At that time it was kind of an unwritten rule that a young umpire won’t work the postseason until at least their sixth year. I was in my fourth year and I got assigned and in my first game, I’m working home plate. That is rare, that you put a first-time umpire working in postseason, that his first game is behind home plate. It’s funny. I was picking up somebody at the airport and Mr. Butler just happened to be at that terminal. He got off the plane and said, ‘When are you playing?’ I said, ‘Tomorrow. I’m pumped up about working. Where are you going to put me?’ He said, ‘Make sure your plate shoes are shined.’”

And he was the home-plate umpire for the final game of the 1983 World Series where Baltimore’s Scott McGregor shut out the Phillies, 5-0. He knew who won that game. “Yeah, you see one team congratulating one another and jumping up and down and the other team walking toward the dugout with their heads down. You knew it was over. And I know that Eddie Murray hit two home runs in that game.”

But for the most part, it’s the plays that would stand out in his memory. “I appreciate the playing of the game and playing the game the right way. A spectacular play? Now, that’s a big-league play. Like that kid catching the ball over the bullpen wall last night and the other kid in center field reaching over the Red Sox bullpen and pulling a home run back off the field. You appreciate those plays and it makes you pay attention to that kid the next time he’s playing, too. I’ve seen this kid do something special and he’s got the potential ability to do something special again. Like this kid Trout, when he walks on the field every day. He’s got the potential to do something that you might not have seen. He plays the game the right way. Robin Yount did it and George Brett did it. Ripken did it. Kirby Puckett did.

“People have asked me, as you did, do you have any kids? I said no, but if I had a son, I would definitely get a video of George Brett or Cal Ripken or Kirby Puckett or Paul Molitor or Robin Yount and I would sit him in a chair and put that videotape on and say, ‘Here. This is how you’re supposed to play the game of baseball.’”

Palermo remarried in 1985, Debbie Aaron, who worked for a property tax consulting firm.

He worked a total of 1,871 regular-season games, the last being on July 6, 1991 at Arlington Stadium. The Rangers beat the Angels, 4-3, and after the game Palermo stopped by to have dinner at Corky Campisi’s restaurant before returning to the Hyatt. A couple of the waitresses left to go home, and then another restaurant employee shouted out that they’d run into trouble. They were being beaten to the ground in a purse-snatching. Palermo and Terrence Mann ran outside and ended up chasing and catching one of the thieves, but there was a fourth man in a getaway car who circled back and fired five shots, hitting both Mann and Palermo.

“The first three bullets hit T-Mann – one in the throat that entered and exited from right side to left side. The second one hit him in the bicep of his right arm and then the third one hit him in his thigh. The fourth bullet missed all of us and it hit a brick wall behind us – Mrs. Baird’s Bakery. The fifth one hit me at belt level and took a path through my body, hit my left kidney and bounced off the kidney, hit the abdomen, and then went straight down and struck my spinal cord and then went out my left side. It hit what they call the cauda equine, the peripheral nerves that come out the bottom of your spinal cord that enervate your muscles in your lower extremities. I was paralyzed immediately.”

The police had already been called and they caught the shooter, who was sentenced to 75 years in prison.

Palermo was treated at Parkland Hospital in Dallas, the same hospital to which President John F. Kennedy had been taken after he was shot. It was a long, very difficult, and never-ending rehabilitation, and more than a dozen years later, Palermo still walks with supports. But he put in the months and months of work, and was eventually able to be assigned new responsibilities.

In 1994, he was asked to prepare a report on the pace of the game and presented it in June 1995 at the owners’ meeting in Minneapolis. In 1999, he started working for Sandy Alderson and in 2000 in Baseball Operations. Palermo now reports to Chief Baseball Officer Joe Torre.

“I’ve become basically a supervisor and instructor, where I supervise stuff and evaluate umpires. We kind of handle everything that takes place as far as on field. We give a talk to the teams during the course of spring training. We go to visit with all the managers, coaches, and general managers. Tell them of the new procedures, if there are any. There’s a host of duties. I also go out to the Fall League for seven weeks. We get 12 umpires to find out if they have the…to become major-league umpires.

“Frank Pulli was the first one named. Frank and I for a few years were the only two that worked for Major League Baseball. We started to add as time went on and as we implemented more and more things, the staff grew.”

Asked to describe his work as Major League Supervisor of Umpires, “To describe the position, I’d like to think of it as either a liaison or a conduit between management and umpires, so that you can bring the mentality of management to the umpires and let them understand it and try to bring the mentality of the umpire to management so that management can understand it. It’s a two-way street.

“This program all started after the breakup of the union in 1999 and the formation of another union. We were brought on board, starting in 2000, and even though I hadn’t umpired since 1991 – I’d been off the field for 10 years – you have to build up this trust. Through time. This is very new. They only had one supervisor in each league. Now we have five or six guys going around the big leagues, and four or five guys in the minor leagues.

“I don’t like to think of it as constructive criticism. It’s not tearing you down. It isn’t criticism. It’s constructive advice. Try not to commit a mistake that I made. You’re doing this and I made a mistake because of that. I’m trying to be proactive rather than reactive. That’s what teaching umpiring is all about. You teach them as much as they can possibly take it. I’ve had people tell me, ‘Steve, we’re trying to teach them math and you’re trying to teach them trigonometry.’ How do you know they can’t do trigonometry? Unless you’re talking with them, you don’t know. And if you see they can’t do trigonometry, you can go back to basic math. I believe you keep putting more and more and more out there, and then you find out where’s their threshold. Once you know that, then you understand and then you work with them. Then you can formulate a really good umpire regardless.”

The umpire observers file their reports, for every game, submitting four reports – one for each umpire. “I get to see everybody’s evaluations and they get to see mine. They go through Major League Baseball.”

And he’ll supply feedback directly to the umpires. “I let them decompress after a game. Give them a day to think about it. The only time you usually don’t have a chance is on getaway day. There might be a phone call, once they arrive in their next city. I might give a call and let them know. Generally, what I’ll do is I’ll deal with the crew chief and say, ‘Tell Tom this, tell Bill this, tell Dick this…This was excellent. He might need work on this….’ Whatever it might be. Generally, that’s what we do. We go through the crew chief and then the crew chief – being in that position – he’s going to let it all filter down. That’s part of his job. That’s part of his crew chief responsibility. It’s not only himself, but he’s got three other people. We give it to them, because we know that they can handle it.”

Palermo died at the age of 67 on May 14, 2017, due to complications from lung cancer.

An earlier version of this biography was included in “The SABR Book of Umpires and Umpiring” (SABR, 2017), edited by Larry Gerlach and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations from Steve Palermo come from interviews with the author on August 20 and 21, 2014.

2 His employer during his years in the minor leagues was Baseball Umpire Development – “the minor-league arm of Major League Baseball. They’re the ones who provided, or assigned, umpires to the Triple-A leagues, the Double-A leagues, the A+, rookie ball. I think they started the school in 1970. It was two years before I got down, when Baseball invested all this money. They basically subsidized umpire school at that time. It cost me $300 to go down, but Baseball picked up the rest of it. They said, ‘We have training for all the players, but for umpires we have nothing. We just go kind of searching for them and then try to train and develop them, stick them in the minor leagues.’ We did have the Al Somers School, which became the Harry Wendelstedt School. The only other thing was Baseball Umpire Development, and that was directly supported by the major-league teams that said, ‘Let’s develop the umpires, too.’”

3 E-mail to author, September 21, 2014.

4 Author interview with Steve Palermo, January 15, 2015.

5 Ibid.

Full Name

Stephen Michael Palermo

Born

October 9, 1949 at Worcester, MA (US)

Died

May 14, 2017 at Leawood, KS (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.