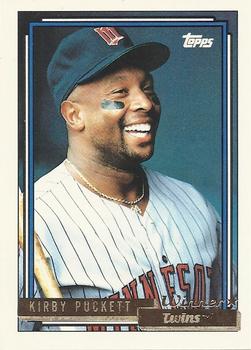

Kirby Puckett

On his way to the big leagues, he outshined his teammates every step of the way. Once in the majors, he quickly established himself as one of the legends in Minnesota Twins’ history, taking his place with stars like Harmon Killebrew and Rod Carew. His image as a player and a person was sterling throughout his career, although his reputation became tarnished by allegations of abusive behavior after his playing days, which ended prematurely because of an eye disease.

On his way to the big leagues, he outshined his teammates every step of the way. Once in the majors, he quickly established himself as one of the legends in Minnesota Twins’ history, taking his place with stars like Harmon Killebrew and Rod Carew. His image as a player and a person was sterling throughout his career, although his reputation became tarnished by allegations of abusive behavior after his playing days, which ended prematurely because of an eye disease.

Kirby Puckett was made for baseball, and, it seems, baseball was made for him. It was baseball that Puckett clung to as he beat the lure of crime and drugs in the projects of South Chicago, where he had grown up, the youngest of nine children of Catherine and William Puckett.

Puckett was born March 14, 1960. However, throughout his playing career, his birth year was listed as 1961, making it appear that Puckett was a year younger than he really was. Often playing with kids several years older, Puckett learned his craft in makeshift ball games on the asphalt and hard dirt fields that surrounded the housing project. He didn’t play a baseball game on a grass diamond until he was a teenager, two years after the Puckett family had moved out of the projects.

At Calumet High School in Chicago, Puckett played third base and received All-America honors. But few scouts–either from professional teams or colleges–came to watch Calumet’s games. The only scholarship offer Puckett received after graduation was from Miami Dade North Junior College in Florida.

Although Miami Dade had a good baseball program, Puckett didn’t feel like venturing far from home. Besides that, he decided to get a dose of the real world by working. Puckett got a bigger dose than he bargained for. He was making good money installing carpeting in Thunderbirds at a Ford plant when he was let go by the company. Unsure what to do next, Puckett worked at a temporary job and then heard about a major-league baseball tryout camp being held in Chicago. He attended the camp and caught the eye of Dewey Kalmer, head baseball coach at Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois. Kalmer offered Puckett a scholarship to play for the Braves. Puckett jumped at the chance to play ball and get an education only a few hours from home.

The Bradley infield was stocked with seniors, leaving little chance for a freshman to break in. Rather than languish on the bench, Puckett agreed to give the outfield a try. He fit right into the lineup and led the team with eight home runs. This would be his only year at Bradley. Soon after Puckett had started college, William Puckett died. The following year, Puckett transferred to Triton Junior College, on the outskirts of Chicago, so he could be closer to his widowed mother.

Before starting at Triton, though, Puckett spent the summer of 1981 playing for the Quincy team in the Central Illinois Collegiate League. This was the summer that major-league baseball players were on strike for nearly two months. With revenues barely trickling in because of the strike, many major-league teams cut back on operations, such as scouting. Jim Rantz–then the assistant farm director for the Minnesota Twins–used his free time to visit his son, Mike, who was playing for Peoria in the Collegiate League. By chance, Peoria was playing Quincy the night that Jim Rantz showed up. Rantz had come to watch his son, but it was Puckett who caught his eye. “He had something like four hits and made a great throw from center field to throw out a runner at the plate,” Rantz recalls. “And the best thing was that there were no other scouts in the stands to see him.”

Based on Rantz’s report, the Twins selected Puckett with their first pick (the third overall) in the January 1982 amateur draft. They were unsuccessful in their first attempts to reach agreement on a contract with Puckett, who played that spring for Triton. Puckett was spectacular, hitting .472 with 16 home runs (including four in one game) in 69 games. He led Triton to the national finals and was named the Region IV Junior College Player of the Year.

His value now firmly established, Puckett signed with the Twins and reported to their rookie team in Elizabethton, Tennessee. He led the Appalachian League in a number of offensive categories, including batting average, runs, hits, total bases, and stolen bases. Baseball America named him the league’s Player of the Year.

In 1983, Puckett was promoted to the Visalia Oaks and was named Player of the Year again, this time in the Single-A California League. In addition to hitting safely in the first 16 games of the year and hitting .314 for the season, Puckett also displayed his strong arm, leading the league’s outfielders in assists.

Puckett jumped two classes in 1984, moving to the Triple-A International League with the Toledo Mud Hens. Two coaches with the Twins–Tom Kelly and Rick Stelmaszek–had worked with Puckett in instructional leagues the previous two seasons and even suggested he might already be ready for the majors.

But the Twins didn’t want to rush Puckett–at least not that much. They waited until May before calling him up. The Twins were in California and the Mud Hens in Maine when the call came. Puckett’s cross-country journey was a nightmare. With his connecting flight in Atlanta held up by a long mechanical delay, Puckett got to Los Angeles International Airport hours behind schedule and hopped a cab for Anaheim Stadium. The fare by the time he got there was $83, far more than Puckett had in his pocket. He rushed into the stadium and got the money to cover the fare. It was too late to play in the game, though; manager Billy Gardner had already scratched Puckett’s name from the starting lineup.

His chance came the next night when he became the 298th member of the Minnesota Twins. He also became only the ninth player in the 20th century to break into the majors with four hits. After grounding out his first trip to the plate, leading off the game, Puckett singled in his next four times up.

The following week, Puckett made his first appearance in the Metrodome in Minneapolis. The recorded attendance for the game was 26,761. In reality, fewer than 10,000 fans saw Puckett’s Minnesota debut. This was the first game of a ticket buyout, orchestrated by the Minneapolis business community, to see to it that the Twins sold enough tickets to avoid being able to exercise an escape clause in their lease and possibly leave the area. Before long, though, real fans were filling the seats at the Metrodome as the Twins found themselves in their first pennant race since 1979. They ended up falling short in the final week of the season, but baseball fever had returned to Minnesota, thanks in large part to the newcomer in center field.

Puckett didn’t homer his rookie season but connected early in 1985. It came at home, a three-run shot off Matt Young of Seattle that just cleared the plexiglass in left field. The plexiglass extension that topped the left-field wall at that time made it harder to hit home runs in the Metrodome. There was a different kind of barrier–at least for visiting batters–in center field. That barrier was Kirby Puckett. Minnesota fans became accustomed to watching Puckett drift back and plant himself on the warning track, then leap high to turn a sure home run into an out. Lou Whitaker of the Tigers learned he needed a bit more loft in a July 26, 1985 game. Detroit trailed, 6-5, with two out in the top of the ninth and Alex Sanchez on second when Whitaker hit a long fly to center. He thought it was good for a two-run homer to put the Tigers ahead, but Puckett had other thoughts. He snared the drive before it could become a home run and ended the game with his catch.

Puckett hit well throughout the 1985 season and had a chance for 200 hits as the Twins concluded the season at home against Cleveland. It looked like he had it when he hit a sharp grounder past first baseman Mike Hargrove. However, the play was ruled an error on Hargrove rather than a hit for Puckett. He still finished with 199 hits, many of them bunt singles that he legged out.

Puckett’s stocky build made him look like he was designed for power rather than speed. He was often compared to two other power hitters with a fireplug look–Jimmy Wynn, the “Toy Cannon” who had a fine career with Houston and Los Angeles, and Hack Wilson, a great slugger for the Chicago Cubs in the 1920s and 1930s. But Puckett displayed little power when he broke in. He followed up his homerless rookie year with only four home runs in 1985. It was his speed that made him stand out as he racked up triples and stolen bases in addition to the bunt hits.

That changed by 1986. He still had the quickness and speed, but now he added the long ball to his arsenal. Over the off-season, Puckett worked with Twins batting coach Tony Oliva, who helped him develop the leg kick that became his trademark for the rest of his career. The coaching paid off. Puckett didn’t have any homers in the first seven games of the 1986 season but then started connecting steadily. By the end of April, he led the league with 8 home runs, 22 runs scored, and 36 hits; in addition, he had a .396 batting average and 16 runs batted in through just 21 games. This performance earned him American League Player of the Month honors.

He continued the hot hitting into May, homering at Yankee Stadium as the Twins wrapped up a series in New York and moved on to Detroit. A strong wind was blowing in from left field as Puckett led off the game against the Tigers’ Jack Morris. But the wind wasn’t strong enough to hold up Puckett’s drive as he homered on the first pitch of the game. The next night he did it again–homering on the first pitch of the game. It was his ninth home run in the Twins’ last 11 games and enough for manager Ray Miller to consider spots other than leadoff for Puckett in the batting order.

By the following week, Puckett found himself in the number-two spot of the order in a couple of games. Soon after the All-Star Game–which Puckett started for the first time–Miller called Puckett into his office and said, “You’re my number 3 hitter.”

“Isn’t that the spot for the team’s best hitter?” Puckett asked.

“You’re my best hitter,” Miller replied.

Puckett actually alternated between the number-three and leadoff spots in the order and was batting leadoff in an August 1 game against Oakland, starting the bottom of the first with a triple. Bert Blyleven grabbed the spotlight in the top of the fifth when he struck out the 3,000th batter of his career and went on to fan 15 in the game, tying a Twins’ record. But Puckett got the attention back on himself with a double in the last of the fifth and a single in the sixth. He was just a home run shy of hitting for the cycle and would have at least one more trip to the plate.

He had faced the same situation only a few days before and, needing a homer for the cycle, instead struck out. This time, as he walked to the plate in the eighth, he was determined not to swing for the fences. It worked. Not trying to go deep, Puckett hit the long ball he needed to give him a home run, triple, double, and single in the same game.

Puckett finished the season with 31 home runs, the most he would ever hit in his career. He became the first player ever to be held without a homer in a season with at least 500 at bats to later hit at least 30 home runs in a year. In addition to his batting prowess that season, Puckett won his first Gold Glove (the first of six he would receive for his outstanding play in center field) and finished sixth in the AL’s Most Valuable Player (MVP) balloting.

That fall, Puckett married Tonya Hudson, a Minneapolis woman he met after coming to Minnesota. The Pucketts adopted two infants in the ensuing years, Catherine in 1990 and Kirby Jr. in 1992.

Puckett was anchored in the number-three position in Minnesota’s batting order starting in 1987 and quickly showed that he was well suited for the spot. In the opening game in what was to become a magical season for the Twins, Puckett hit a two-run homer in the last of the third to put Minnesota ahead of Oakland, 2-1. The Twins fell behind again, but Puckett opened the eighth with a single and came around to score the tying run. Then, in the tenth, he dropped a double into right field as part of a game-winning rally. He also showed fans he could still display his old tricks in center field. In the top of the tenth inning, Puckett leaped in front of the center-field fence to rob Mickey Tettleton of a home run that would have put Oakland ahead.

Puckett stayed hot through the first half of the season, sharing the team lead in runs batted in with Kent Hrbek at the All-Star break. He cooled down over the next six weeks and added only three homers and 12 RBI going into the final two games of a weekend series at Milwaukee.

Before the Saturday game against the Brewers, Oliva lectured Puckett about being more aggressive with his bat. Puckett responded with four hits, including two home runs. The next day, he sat on a tarpaulin with Oliva before the game and said, “You know, Tony, I feel great. I feel like something’s going to happen.”

He had good reason for feeling that way. After driving in a run with a first-inning single, Puckett homered in the third to give the Twins a 2-0 lead. Milwaukee came back with three runs, but Puckett singled and scored the tying run in the fifth. Milwaukee retook the lead in the bottom of the inning, but it could have been worse. With the bases loaded, Robin Yount hit a long drive to center that Puckett hauled in with a leaping grab, robbing the Brewer star of a grand slam. Puckett doubled in the eighth as part of a three-run rally that put the Twins back in front. Then in the ninth, with Greg Gagne on first base, Puckett got another chance. This time he went the opposite way this time, drilling a home run to right for his sixth hit of the game. The ten hits in consecutive games set an American League record and tied the major-league mark.

Puckett was back. He kept it up a few days later back at the Metrodome. The Twins trailed Boston by a run with two out and no one on in the last of the ninth. It looked like a Boston win, but the Red Sox still had to face Puckett, who drilled a liner to left for a game-tying homer, a drive that left the yard as quick as any ever hit there. The Twins went on to win in extra innings and, from there, to win the American League Western Division title. This time, Puckett finished third in the MVP voting, behind George Bell of Toronto and Alan Trammell of Detroit.

The Twins were underdogs the entire season but defied the odds and continued befuddling the experts as they polished off Detroit in the league playoffs. Next, they faced against the St. Louis Cardinals in a hard-fought World Series.

The Cardinals held a three-game-to-two lead and had ace southpaw John Tudor on the mound in Game Six at the Metrodome. St. Louis built a 5-2 lead after four-and-a-half innings. If Tudor could last a couple more innings, Cardinal manager Whitey Herzog could get into his bullpen, which had been tough all year. The Twins had to do something quick. They did. Puckett–already with two hits in the game–lined Tudor’s first pitch of fifth the inning up the middle for a single, starting a four-run rally that put the Twins ahead. In the sixth, Puckett walked and scored on a grand slam by Hrbek that broke the game open. For good measure, Puckett led off the eighth with another hit and scored again. The headlines in this game belonged to Hrbek and Don Baylor, whose fifth-inning homer tied the game. Almost overlooked was Puckett’s performance of getting on base five times and scoring four runs. However, a few years later there would be another Game Six that would carry Puckett’s indelible signature.

In the seventh game, Puckett had two hits (tying the Cardinals’ Willie McGee for the most hits in the series) as the Twins beat St. Louis, 4-2, to win their first world championship since moving to Minnesota.

The Twins didn’t repeat in 1988, but Puckett had his best year ever. Over the off-season, he had worked out, lifting weights with Vikings’ punter Greg Coleman and playing basketball. He laid off red meat for a few weeks and reported to training camp both lighter and stronger. Before the season was done, he had collected the 1,000th hit of his career, becoming only the fourth player to reach that level in his first five seasons; Joe Medwick, Paul Waner, and Earle Combs having reached this milestone previously. Puckett topped 100 in both runs scored and batted in; he had over 200 hits, leading the majors in that category as well as in total bases. His .356 batting average was second in the league to Wade Boggs (who won his fourth consecutive batting title and fifth overall), but it was the highest American League batting average for a right-handed hitter since Joe DiMaggio hit .357 in 1941. For the second straight year, Puckett finished third in the league’s Most Valuable Player race.

Puckett’s numbers weren’t quite as good in 1989, but he did hit well enough to lead the American League in batting average, joining Rod Carew and Tony Oliva as the only Twins ever to capture a batting crown. Puckett was in a virtual tie with Carney Lansford of Oakland on the final day of the season. But while Lansford was held hitless, Puckett produced a pair of doubles to finish at .339.

For the third straight year, he led the American League in hits, joining Oliva and Ty Cobb as the only players ever to do that. He continued to show great range in the outfield, tying a league record by recording his fifth consecutive season with 400 or more putouts.

Puckett was being heralded by some as the best player in baseball. The three-year, $9-million dollar contract he signed with the Twins after the 1989 season reflected that status as he became the first player ever to make $3 million a year.

Puckett was a fixture in center field for the Twins, but that began to change in 1990. Before an August game in Cleveland, manager Tom Kelly told Puckett to check the lineup card carefully. When he did, he saw he was starting in right field–the first time in his major-league career he’d be somewhere other than center field. Before this game was out, though, Puckett would be playing three other positions. Shortstop Greg Gagne was removed for a pinch hitter in the top of the eighth. Kelly had a couple players who could play the infield, but he wanted to save them for possible pinch-hitting duty in the ninth. So, to keep the infield together, Puckett was moved to shortstop in the last of the eighth. Before the inning was out, he also played third base and second base as Kelly shifted him around, trying to put him where the ball was least likely to be hit. After the game, Twins’ utility ace Al Newman joked, “I’m glad Puck’s one of us utility guys now. Maybe he’ll raise the salary structure a little.” Kelly did use Puckett in the infield again but not regularly. The move to right field was different. The Twins were concerned about how much center field might be wearing Puckett down. They wanted him with them for many more years and thought an occasional move to right might help preserve his legs. Over the next few years he played both center and right field (and even left field on a couple of occasions), but it wasn’t until 1994 that he moved to right field for good.

The Twins finished last in the American League West in 1990 and no one figured they’d be a contender in 1991–no one, that is, except the Twins. The team struggled through the first two months of the season. But toward the end of May, Puckett and the Twins began to stir. On May 23, Puckett had the second six-hit game of his career; however, Minnesota stranded 21 runners on the bases (in 11 innings) and lost to the Rangers, who won their 10th straight game. The following week, though, the Twins snapped the Rangers’ winning streak at 14–Puckett drove in two runs in the 3-0 win–and then started an even longer streak a few days later. The Twins won 15 games in a row, a team record. It was their 15th consecutive win that finally moved the Twins into first place. Puckett had a home run to tie the game and a single as part of a two-run tenth inning rally in that game.

The Twins went on to win the Western Division title–a remarkable rebound after their last-place finish the year before–and met Toronto in the playoffs. Puckett had just one hit in his first eight at bats but then turned it on and helped the Twins finish off the Blue Jays, four games to one. In the final game, Puckett had a home run and a single, the latter hit putting the Twins ahead to stay. Puckett was named the series Most Valuable Player.

Having won the American League pennant, the Twins faced the Atlanta Braves in a classic World Series that went down to the wire. Five of the games were decided by one run with three games going into extra innings.

As they had been against the St. Louis Cardinals in 1987, the Twins were down three-games-to-two as they came back to the Metrodome. They had to win Game Six or the series would be over. Puckett felt good in batting practice and said to his teammates, “Jump on my back today. I’ll carry us.”

The Twins jumped on early. Puckett tripled home a run in the first inning and came around to score to give the Twins a 2-0 lead. His bat had put the Twins ahead and his glove kept them there. In the third, the Braves had a runner aboard when Ron Gant hit a long drive to left-center. Puckett rushed over–planting himself in front of the Twins’ display of retired numbers that would eventually include his own–leaped and snared the ball before it could bounce off the plexiglass for extra bases. In Minnesota baseball lore, the play has become known simply as “The Catch.”

The Braves did tie the game in the fifth, but Puckett quickly untied it, driving in Dan Gladden with a fly to center. But Atlanta came back again, and the game went into extra-innings. Puckett led of the last of the 11th, facing lefthander Charlie Leibrandt. Leibrandt fell behind in the count, then came in with a change-up that Puckett jumped on. He got all of it, sending the drive over the left-centerfield fence for a game-winning home run.

With his bat and his glove, Puckett had carried Minnesota back to a seventh game, another extra-inning nail biter that the Twins won for their second world championship in five seasons.

Puckett had great season again in 1992. He was named American League Player of the Month in May and June, becoming only the second player to win the honor in consecutive months. Through the season, he never went more than two games in a row without a hit and ended up leading the American League in total bases and the majors in hits and grand slams. He had his highest standing ever in the MVP balloting, finishing second to Oakland’s Dennis Eckersley. But while he was having a terrific year, Twins’ fans wondered if this would be his last in Minnesota. He would be a free agent at the end of the year, and negotiations between the Twins and Puckett had not produced a new contract. When the season was over, Puckett talked to several clubs but, in the end, re-signed with the Twins. He demonstrated his loyalty to Minnesota by signing for less money than he could have gotten elsewhere.

He continued to thrill fans not just in Minnesota but throughout the American League. And he showed what he could do when he had the chance against National Leaguers. In 1993, Puckett was named the All-Star Game Most Valuable Player–the first Twin ever to achieve this–as he homered and had a run-scoring double.

He reeled off more milestones over the next two seasons, getting the 2,000th hit of his career early in 1994. In mid-season, he reached his 2,086th hit–a two-run homer against the Royals–that broke Rod Carew’s team record for hits. The season was shortened because of a strike in August, but Puckett had 112 runs batted in by that time and became the first Twin since Larry Hisle in 1977 to lead the league in RBIs.

Puckett’s consistency both in scoring and driving in runs showed in 1995 when he reached 1,000 in both categories only nine days apart. Later in the season, he hit the 200th home run of his career. He looked like he’d reach 100 RBIs for the season as he stood at the plate against the Indians in the Twins’ final regular-season game. Chuck Knoblauch was on third with one out as Puckett leaned in, hoping to get a pitch he could drive to bring in the run. But the delivery from Cleveland righthander Dennis Martinez was high and tight. The pitch struck Puckett squarely in the face, breaking his jaw and ending his season.

Puckett was back in 1996 and feeling good during spring training. On March 27, less than a week away from the opening of the regular season, the Twins faced the Atlanta Braves and Greg Maddux, who had won the National League Cy Young Award the previous four seasons. Puckett had faced Maddux only once before–grounding out off him in the 1994 All-Star Game–but this time he produced a first-inning single. He got another hit in the game after Maddux had departed before being lifted for pinch-hitter Chip Hale.

That turned out to be Puckett’s final appearance as a player. The next morning he woke up with blurred vision. He hoped the black dot that clouded what he saw out of his right eye would leave, but it wasn’t to be. Puckett held out hope and was on the bench for Twins’ games while on the disabled list through the first half of the season. Finally, in July, Puckett and the Twins faced the reality that his vision would not improve. Puckett announced his retirement in a tear-filled ceremony at the Metrodome.

Even with his career prematurely ended, Puckett had compiled a magnificent résumé. He had been an American League All-Star the final ten years of his career. Five times he was named the Twins Most Valuable Player and finished in the top five in the American League voting on three occasions. Three times he led the American League in putouts and twice either tied or led the league in assists. For his efforts, he was rewarded with a Gold Glove six times.

He’ll be remembered for his free-swinging approach at the plate–“I’m just up there hacking,” was his standard line–that produced such impressive numbers. But more than that, he’ll be remembered for his smile, his infectious enthusiasm, and his competitive nature that has made him the most popular athlete in the history of Minnesota sports. Even with the bad break that ended his career, Puckett refused to feel sorry for himself. He assured fans that he was fine and had no worries for the future.

That seemed to be the case in the next few years. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in January 2001 in his first year of eligibility and inducted that summer. Within a year, however, came the beginning of a series of disturbing reports that caused some to question their perception of Puckett, with many fans going into denial over the news.

In early 2002 came the news that Tonya Puckett was seeking a divorce following years of alleged abuse from her husband. Tonya had called local police on December 21, 2001, several days after a phone conversation with Kirby in which she said he threatened to kill her as they argued over Kirby’s alleged infidelity. In a police report Tonya also alleged that in the past, Kirby had choked her with an electric cord, put a pistol to her face as she held her daughter, then two years old, and, on another occasion, used a power saw to cut through a door to get at her.

Puckett denied ever threatening to kill his wife. It did come out, however, that he had a long-time mistress, one who would eventually become fearful of him herself and would seek a protective order to keep him away from her.

Soon more serious charges emerged. In September 2002 a woman accused him of dragging her into a men’s room and groping her at a restaurant in a suburb of Minneapolis. Puckett was charged with false imprisonment, a felony, and gross misdemeanor sexual conduct. The trial was held in early 2003, and Puckett was acquitted. However, questions remained about what had really happened in the restaurant that night.

In addition to his separation and subsequent divorce, Puckett and the Twins parted ways. Puckett had been a vice president, serving largely in a public relations capacity as the Twins sought public funding for a new stadium. Puckett moved to Arizona. His weight, which had steadily risen toward the end of his playing career, continued to balloon.

It was reported that he was well over 300 pounds when he suffered a stroke on Sunday, March 5, 2006. The next day he died.

Even in death, controversy surrounded Puckett as Jodi Olson, who had been engaged to him, battled with Tonya Puckett, acting on behalf of Catherine and Kirby Jr., over everything from Puckett’s possessions to the disposition of his cremated remains.

Minnesotans mourned the passing of one of the state’s most popular personalities ever. The grief was in some ways compounded by the revelations in recent years about a person many people idolized to an extreme degree. Learning the truth wasn’t easy for many, particularly those in Minnesota, and some had trouble reconciling the Puckett they had chosen to envision and the real Puckett–a human being with many virtuous qualities as well as some flaws.

Those unable to acknowledge the flaws directed their anger at the messengers reporting the news as well as those behind the allegations–“scorned women” as seen by those straining to hang on to their pristine visions of Puckett.

An article by Frank Deford in the March 17, 2003 Sports Illustrated stirred more resentment in Minnesota. Yet Deford’s opening paragraph may well sum up Puckett and his legacy as well as anything written about him:

In the final analysis, all they really know now in Minnesota is that he was one whale of a baseball player. They’ll never be so sure of anyone else again. So, maybe that’s a tough lesson well learned. The dazzling creatures are still just ballplayers; don’t wrap them in gauze and tie them up with the pretty ribbons of Nice Guy or Boy Next Door (and certainly not of Knight in Shining Armor). On the other hand, what a price did fans pay to lose their dear illusions. You see, when the hero falls, maybe the hero worshipers fall harder. After all, Kirby Puckett always knew who he was. Well, he probably did. Nothing seemed to faze him. It was all the other folks who decided he must be someone else, something more. Yeah, the lovable little Puck was living a lie, but whose lie was it?

Notes

Some of the information related to Puckett’s career came from a special section, “Remembering Kirby,” in the Friday, September 6, 1996 issue of the Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities. This section contained reprints of a number of Star Tribune articles from previous years.

Regarding the eventual correction in Puckett’s birth year, Doug Walden of the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Giamatti Research Library said that prior to Puckett’s 2001 induction, the Minnesota Twins informed Jeff Idelson, the Hall of Fame’s vice president of communications and education, that his birth day had been misreported and was actually March 14, 1960.

Sources

I Love This Game! My Life and Baseball, by Kirby Puckett. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993

“Puckett Remembers His Mom Quite Fondly–Every Day” by Curt Brown, Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, Sunday, May 13, 1990, p. 1C

“Puckett’s Zeal Is Still for Real” by Patrick Reusse, Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, Sunday, March 21, 1993, 1C

“Tonya Puckett Seeks Divorce from Kirby after Alleged Threat” by Jim Adams, Pam Louwagie, LaVelle E. Neal III, Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, Saturday, January 12, 2002, p. 1B

“Puckett Didn’t Sexually Assault Woman, Lawyer Says; Accuser Called 911 from Eden Prairie Restaurant” by Jim Adams, Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, September 21, 2002, p. 1B

“The Secret Life Of Kirby Puckett” by Bob Sansevere, St. Paul Pioneer Press, Tuesday, December 17, 2002, p. 1A

“The Rise and Fall of Kirby Puckett” by Frank Deford, Sports Illustrated, March 17, 2003, p. 58

“He Was Born in ’60, Not ’61” by LaVelle E. Neal III, Star Tribune: Newspaper of the Twin Cities, Tuesday, March 7, 2006, p. C6

Full Name

Kirby Puckett

Born

March 14, 1960 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

March 6, 2006 at Phoenix, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.