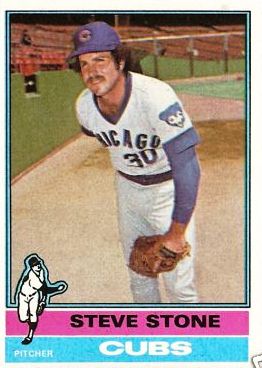

Steve Stone

Rene Descartes: “I think; therefore, I am.”

Steve Stone stepped off the mound, mopped his brow, and took a long look at the crowd in the stands. “This is nice,” he said to himself. But it wasn’t always this way for Stone. For some time, he had struggled to find himself as a pitcher and as a person. Through self-examination, Steve had become a fine pitcher and an insightful person.

He was not your ordinary ballplayer. He wrote poetry, authored a book, played chess, and was good at table tennis. He was a restaurateur nicknamed the “Galloping Gourmet” by Chicago newspapers. He became a believer in positive and metaphysical thinking. When he injured his arm, he refused surgery and cortisone shots and instead underwent cryotherapy, a procedure in which the arm is frozen and then exercised to increase blood flow. A true Renaissance Man.

Stone was Jewish. The Jewish culture emphasized education and intellectual accomplishment. Parents of Jewish athletes would say, “Are you meshugah?” (crazy). “Nice Jewish boys and girls don’t engage in sports.”

Henry Ford, a notorious anti-Semite as well as a mechanical genius, proclaimed, in 1921, “Jews are not sportsmen. … Whether this is due to their physical lethargy, their dislike of unnecessary physical action or their serious cast of mind, others may decide. … It may be a defect in their character, or it may not; it is, nevertheless, a fact which discriminating Jews unhesitatingly acknowledge.” Steve Stone stood this statement on its head. He was a good athlete and combined his athletic ability with education, writing, and thought.

For nine years in the major leagues, Stone labored but all he had to show was a 78-79 won-lost record. A journeyman pitcher, he had a good but not terrifying fastball and a solid curve. He was not physically imposing, standing a bit under 5 feet 10 and weighing 170 pounds Baseball people felt that he could not go an entire season without breaking down, especially in the dog days of July and August.

Steven Michael Stone was born on July 14, 1947, in Euclid, Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland, to Paul and Dorothy Stone, Orthodox Jewish parents. Times were not easy for the Stones. His mother was a waitress and his father changed records in juke boxes. In time, Paul became an insurance salesman and the family moved to a more upscale but still modest neighborhood. Dorothy and Paul encouraged Steve to engage in sports. Both parents played softball and tennis. They bought Steve his first baseball glove, a catcher’s mitt, when he was 2 years old. Steve was always throwing a ball. Sometimes against a wall, sometimes against some neighbor’s steps, and, on occasion, through some neighbor’s windows. Steve did not lie to his parents about breaking the windows. Punishment for these misdeeds was banishment to his room. There were times when Steve would come home and immediately go to his room. A phone call would follow shortly after, announcing another broken window. Papa Stone would always pay for them.

It was at a Little League game when Steve was 9 that he switched from catching to pitching. His father, coach of the team, had to pull the pitcher out of a game after he had walked nine straight batters. Mr. Stone put his son into the game as the pitcher, with the admonition, ” Just throw the ball over the plate.” Steve did just that and he was now a pitcher. The tools of ignorance became a thing of the past.

After Steve became an established professional ballplayer, the following often occurred: “Meet my son the doctor,” says one woman to Mrs. Stone, who she replies, “Meet my son the ballplayer.” The other woman responds, “Wouldn’t you rather have a son who is a doctor?” Mrs. Stone answers, “Absolutely not.”

At Charles F. Brush High School, Stone was an all-around athlete. He played baseball, tennis, and golf. In 1963, he pitched victories in both halves of a doubleheader in the Class D city playoffs. In 1968, Steve pitched in the Cape Cod League in Massachusetts and had an earned-run average of 2.00.

At Kent State University, he played baseball, bowled, and was on the volleyball and tennis teams. But it was baseball that he most enjoyed. Steve was selected to the All Mid-American Conference baseball team. When he was a junior, he was named captain of the baseball team. His catcher was Thurman Munson. In 1970, Stone graduated with a teaching degree in social studies.

Chosen by the San Francisco Giants in the fourth round of the 1970 offseason draft, Stone was sent to Fresno of the California League. From July 17 to August 22, he won seven straight decisions, including three shutouts. For the season, he won 12 and lost 13, with a 3.16 earned-run average. He began the next season with Amarillo in the Texas League, where he hurled in 19 games with a 9-5 record. During the season, the Giants moved him up to Phoenix of the Pacific Coast League, where he was 5-3 with a 1.71 ERA.

When Stone was promoted to the San Francisco Giants in 1971, someone told him of the Jewish ballplayers who had played for the New York Giants, such as Sid Gordon, Phil Weintraub, Harry Danning, and Andy Cohen, none of whom, he said, he could identify with. “A guy my age,” he volunteered, “can only identify with Sandy Koufax.” And he rejected manager Charlie Fox‘s philosophy that the only way a ballplayer could perform well in the majors was to chew tobacco, wear a sloppy uniform, and “not be afraid to get a bloody nose.” Stone felt that chewing tobacco would make him sick to his stomach, wearing a sloppy uniform would not make him a better pitcher, and a bloody nose was not his idea of a good time.

Steve made his major-league pitching debut on April 8, 1971, starting against the San Diego Padres at San Diego. The first batter he faced, Dave Campbell, singled, and the next, Larry Stahl, hit a home run. Two of the next three batters got hits and Stone was down, 3-0, after the first inning. He held the Padres scoreless in the second and third innings and was lifted after a leadoff double in the fourth. The Giants went ahead with three runs in the seventh, but the Padres pulled out a walk-off victory in the ninth. Appearing in 24 games for San Francisco, with 19 starts, he won 5 games and lost 9, with a 4.15 earned-run average. Before the season was over, the Giants sent him down to Phoenix, where he went 6-3 with an ERA of 3.98. Returning to the Giants in 1972, he was 6-8 in 27 games, 16 of them starts, with a good earned-run average of 2.98. A sore arm cropped up during the season, and after the season, the Giants traded Stone and outfielder Ken Henderson to the Chicago White Sox for pitcher Tom Bradley.

With the White Sox in 1973, he was used as both a starter and reliever, posting a 6-11 record with an earned-run average of 4.24. Again Stone was traded at the end of the season, this time to the crosstown Chicago Cubs, one of four White Sox sent to the Northsiders for Ron Santo.

With the Cubs in 1974, Stone turned in his first winning season, with an 8-6 record (23 starts) and a 4.14 earned-run average. In 1975, appearing in 33 games, all but one of them as a starter, he improved to a record of 12-8 with an ERA of 3.95. He struck out 139, had six complete games, and hurled one shutout.

Because he felt he had had a decent year with the Cubs, Stone expected to get a pay raise in 1976. Instead, the Cubs asked Stone to accept a pay cut. He declined the “offer” and played out his contract.

Stone’s salary problem was exacerbated when he suffered a torn rotator cuff early in the season. The Cubs wanted him to have surgery. But Stone refused. The Cubs then asked him to take cortisone shots and again he refused.

Stone found his own doctor, a kinesiologist, from the University of Illinois. The doctor put Stone’s arm through a series of treatments in which the shoulder was frozen and then exercised, in order to increase the blood circulation to the part of the body undergoing exercise. The exercises were also intended to strengthen Stone’s arm. The result was an astounding success. Free of his contractual obligations with the Cubs, he was courted by five teams for the 1977 season. Steve decided to go back to the White Sox, with a salary of $60,000. White Sox owner Bill Veeck took a chance with Stone and he delivered with a 15-12 record.

Stone got a raise to $125,000 for 1978. He finished that season with a 12-12 record. At the end of the season, Stone decided to cast his lot as a free agent again, and again he received five offers. This time, Stone, who hadn’t yet played in the postseason, picked a team with a chance to win it all, the Baltimore Orioles. He signed a four-year deal with the Orioles for $760,000.

Steve was feeling good; he had an excellent contract and a solid team to play on. But disappointment soon followed. Orioles manager Earl Weaver told Stone that he would be the fifth pitcher in a rotation of four–in other words, a spot starter. By the All-Star break, his record stood at a disappointing 6-7 with an earned run average of 4.40.

Stone decided to take stock of himself with the intention of improving his pitching. He decided, “No one who has ever played this game has said it was anything less than eighty percent mental.” He sought advice on pitching from Oriole pitchers Jim Palmer and Mike Flanagan. He began to follow fixed routines. He would listen over and over to the same music and eat the same meals. He meditated and talked to a psychic. Doug DeCinces, an infielder, told Stone that the players were concerned about his taking too much time between pitches. Steve drastically speeded up his time between pitches. The fielders responded and actually looked forward to playing behind Stone. Ever the thinking man, he reasoned to himself that perhaps the problem of his taking too much time between pitches was due to a lack of confidence.

Stone tried to reconnect with his boyhood idol, Sandy Koufax, by reading his autobiography five times. He changed his uniform number from 21 to Koufax’s number. 32. Stone went to the mound every time with the firm idea that he was going to win, the fielders behind him would make the plays, and he would walk off the mound victorious. He taught himself to believe in himself. Stone did not lose another game after the All Star break and wound up with an 11-7 won-lost record and an ERA of 3.77.

Nine years had come and gone for Steve Stone as a major league pitcher and he had a mediocre record of 78-79. The 1980 season started and Stone settled in for his tenth year in the majors. He had been with four teams, the Giants, the White Sox, the Cubs, and now the Orioles.

Little did anyone envision what was to be a great season for Steve Stone. He was masterful, winning 25 games and losing only 7, with an earned-run average of 3.23. He had a winning streak of 14 games. He pitched three scoreless innings in the All-Star Game. He won the Cy Young Award as the best pitcher in the American League. Steve accepted the award with grace and gave credit to his teammates for their clutch hitting, strong defense, and solid relief pitching. The journeyman had risen to star status, if only for one year.

How did this turnaround happen? Stone had decided before the season that he would throw many more curveballs than in previous seasons. He knew it would put a greater strain on his arm. It paid off for one year.

With a remarkable season behind him, Stone had high hopes that 1981 would be as successful as 1980. But it was not to be. Steve had a miserable season, pitching in only 15 games with a 4-7 record. His decision to throw many more curveballs resulted in tendonitis, so severe that he retired as a player after the 1981 season. Curveball after curveball had wrung out his arm. His career totals were 107 wins, 93 losses, and an earned-run average of 3.97. Though disappointed, Stone had ended his career with a better than mediocre record.

Surgery, cortisone shots, and trying to hang on as a hurler were not options for Stone. “I had seen all facets of the game,” he said. “I had been a bad pitcher and a good pitcher. I had been a mediocre pitcher and a great pitcher. I didn’t want to go back to being a mediocre pitcher anymore.”

Stone turned poet to sum up his career and the vagaries of being a professional ballplayer:

Your supreme effort of yesterday may

fall short of winning tomorrow — then what? …

You have to go out tomorrow and win

again because the people like their heroes

A day at a time.

The top of the world and the bottom aren’t

really that far apart — now, are they?

Still, Stone could joke about his career. He said, “I can say honestly and unequivocally that I am the best right-handed Jewish pitcher to come into the majors in the past 20 years –mainly because I don’t know of any others.”

His playing days over, Stone began a career in broadcasting. In June 1982, he teamed with Al Michaels, Keith Jackson, Don Drysdale, Bob Uecker, and Howard Cosell to make up two teams of three apiece on ABC’s Monday Night Baseball.

Stone was a committed Jew and never found that his Jewishness was any obstruction to becoming a baseball player. He told writer Michael Elkin that he had had “a regular Jewish upbringing” while growing up in Cleveland. “We were affiliated with a Conservative temple, but as I got older I became more Reform.”

After ending his relationship with ABC, Stone became a color commentator for the Chicago Cubs on WGN. He teamed with Harry Caray from 1983 to 1997. Caray was a mentor to Stone. He told Stone, “Be yourself on the radio, be human; that will help you identify with the fans more readily.” After Harry Caray died in February 1998, Steve was paired with Chip Caray, Harry’s grandson. In 2000, Steve left the broadcast booth because of ill health, returning for the 2003 and 2004 seasons.

As to his personal life, Stone plays it very close to his vest. He was married when he was 23 years old to a girl named Nancy, but they divorced after 2 1/2 years. In 2006 he married Lisa, a family attorney.

After the 2004 season, Stone was unhappy that the Cubs hierarchy had let Chip Caray slip away to the Atlanta Braves radio and television scene. Stone and Chip, like his grandfather Harry, were a great team in the booth and enjoyed each other’s company. When the Cubs front office failed to meet Chip Caray’s demands, and let him get away, Steve resigned. According to reports, he would have stayed on if Chip had been signed.

However, there was another important issue that triggered his resignation. On September 30, after the Cubs had ruined their chances for a playoff spot, Stone gave his appraisal of why things had gone wrong. He described the team as “(a) bunch of talented guys who want to look at all directions except where they should really look and kind of make excuses for what happened. … At the end of the day, boys, don’t tell me how rough the water is, you bring in the ship.”

The next day, Stone was called on the carpet by Cubs president Andy MacPhail, general manager Jim Hendry and manager Dusty Baker. They were upset by his comments and a rift developed between the Cubs’ brain trust and Stone. Less than a month later, on October 28, 2004, Stone resigned.

Very popular with Chicago Cubs fans, Stone was not that popular with the Chicago ballplayers because of his criticisms. The fans and baseball experts were amazed by his insight and ability to predict what would happen next in baseball situations. They enjoyed his high energy in pointing out the nuances of the game. Stone announced his resignation before the end of the season. After the Cubs’ last home game ended, fans at Wrigley Field rose in unison, saluted Steve, and wished him a happy life.

Stone has spent 15 years in the Cubs’ radio booth with Harry Caray. When Caray died on February 18, 1998, Stone lost a close friend as well as a mentor. With Barry Rozner, a Chicago area sportswriter, he wrote a book, Where’s Harry?, which celebrated the life of Caray. It took the reader through Harry’s painful childhood as an orphan and through his great years as a Cubs broadcaster. It revealed a man who told it straight from the shoulder: “Harry was one of those people who was what you see is what you get. He was outrageous and wildly entertaining.”

Stone kept busy. As of 2008, he had an online site on which he answered questions from fans. A Chicago resident, he did three radio shows a week on WSCR, and on the same station he was in the television booth for White Sox games with former pitcher Ed Farmer. Stone also did occasional broadcasts on ESPN radio and TV. He owned restaurants in Chicago and Scottsdale, Arizona. He wrote poetry and played chess and ping pong.

Still, there was one ambition that eluded him: to be the general manager of a major-league team or to be an owner or part-owner of a team. Why were these doors closed to him? He was too much the outsider.

Asked what he would have done if he had not played professional baseball, Stone told an interviewer in an article on file at the Baseball Hall of Fame, “I had a teaching degree and I was planning to be a coach probably at the high-school level and then working my way up to college. I majored in history and government, so I probably would have been a history teacher and a baseball coach. I would have been involved in baseball in some way because of my love for the sport.”

Asked whom he admired in baseball, Stone mentioned Edward Bennett Williams, the former owner of the Baltimore Orioles. “He was as smart a man and as tough a lawyer as I’ve ever seen in my life. I could ask him anything and he knew the answer,” Stone said. He also had praise for Bill Veeck.

Stone’s father played a large part in his road to the major leagues. Essentially he taught Steve his pitching motion. When Stone was a youngster, his father told him that he should develop a smooth motion and that as he matured and got bigger and stronger he would be able to throw harder. As it turned out, Stone was a pony sized hurler and in his best season, 1980, relied on his curveball as his out pitch. However, the greatest asset Steve Stone brought to the mound was his mental approach: I think; therefore, I am going to win.

Steven Michael Stone stepped off the mound, mopped his brow, surveyed the crowd in the stands, and inhaled deeply. The thinking man knew he had drunk it in, had felt it, and that made him smile.

Steven Michael Stone, who began life in very modest circumstances, had attained the American Dream. Steve Stone has marched to his own drummer. He has paved his own road in life. As that famous singer crooned, “I did it my way.”

Sources

Baseball Hall of Fame Archives, Steve Stone Items. Cooperstown, New York.

Horvitz, Peter, and Joachim Horvitz. The Big Book of Jewish Baseball. New York: SPI Books, 2001.

Levine, Peter. Ellis Island to Ebbets Field: Sport and the American Jewish Experience. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Ribalow, Harold U., and Meir Z. Ribalow. Jewish Baseball Stars. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1984.

Steve Rosenbloom, Rosenblog: http://blogs.chicagosports.chicagotribune.com/rosenblog.

Steve Stone online site: http://www.stevestone.com/stevespitch.html.

Stone, Steve, with Harry Rozner. Where’s Harry? Steve Stone Remembers His Years with Harry Caray. Dallas: Taylor, 1999.

USAToday.com.

Picture Credits

The Topps Company

Full Name

Steven Michael Stone

Born

July 14, 1947 at Euclid, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.