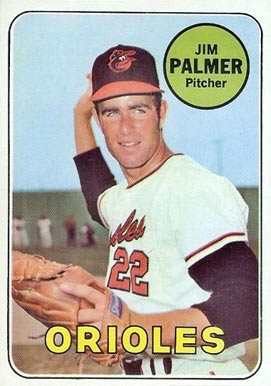

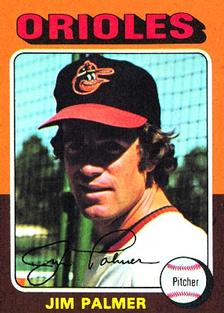

Jim Palmer

In an era filled with pitching stars, many of them working for the Baltimore Orioles, it took Jim Palmer a few years to rise to the top of the heap. Once he did, he became the greatest pitcher in his league for a number of seasons, and one of the best pitchers who ever lived. Along the way, he achieved success as a model and as a television broadcaster, becoming one of the sport’s most visible and successful figures for several decades.

In an era filled with pitching stars, many of them working for the Baltimore Orioles, it took Jim Palmer a few years to rise to the top of the heap. Once he did, he became the greatest pitcher in his league for a number of seasons, and one of the best pitchers who ever lived. Along the way, he achieved success as a model and as a television broadcaster, becoming one of the sport’s most visible and successful figures for several decades.

Jim Palmer was born on October 15, 1945, in New York City. When he was just two days old, he was adopted by Moe Wiesen, a wealthy executive in the garment industry, and his wife, Polly Kiger Wiesen, who owned a dress shop. The newborn was named James Alvin Wiesen, and he was joined by sister Bonnie, who was 18 months older but adopted about the same time. Moe Wiesen was Jewish and Polly was Catholic, but religion did not play a big role in the family’s upbringing. They lived at first in a large house on New York’s Park Avenue, joined by several servants. They later moved north to Westchester County, where Jim attended schools in Rye and White Plains. He and his neighbors had large houses and property large enough to allow the playing of baseball in the front yard.

When Jim was 9 years old Moe Wiesen died, and Polly soon moved with her two children first to Whittier, California, and then to Beverly Hills. While in California, Polly married Max Palmer, a character actor who had appeared in Dragnet, Highway Patrol, Playhouse 90 and many other television shows. (There was another Max Palmer in movies at the time—an 8-foot-2 inch man who played monsters in B-movies and later became a professional wrestler. Some web sites have conflated the two Max Palmers, even suggesting that Palmer’s stepfather was a pro wrestler.) Max Palmer eventually adopted Jim and his sister, and Jim became very close to Max.

The boy who was now Jim Palmer dreamed of becoming a baseball player, and starred in Little League, Pony League and the Babe Ruth League. Before he started high school the Palmers moved to Scottsdale, Arizona, where Jim earned all-state honors in baseball, football, and basketball, and a 3.4 grade point average in school. On the baseball team he pitched and played center field, both very well, while he was a high-scoring forward in basketball and a receiver in football. He had several college offers, and considered UCLA, USC and Stanford, and later briefly enrolled at Arizona State in nearby Tempe.

After his high-school graduation, Palmer played summer ball for a team in Winner, South Dakota, a team that included future major leaguers Jim Lonborg, Merv Rettenmund, Bobby Floyd, and Curt Motton. The club lost in the league finals, but Palmer impressed Baltimore Orioles farm director Harry Dalton, who scouted the series. Some league observers thought the 17-year-old Palmer threw harder than anyone they had ever seen.1 On the 1,200-mile drive home, a friend of Palmer’s (driving Palmer’s car) fell asleep at the wheel, and the car careened into a ditch and flipped several times. There were no seatbelts in the car, and Palmer escaped with a sore left knee, an injury that eventually required surgery. The Orioles were unaware of the injury when they signed Palmer to a $50,000 contract right after he returned home.

Just before heading to spring training, Palmer married Susan Ryan, whom he had known throughout high school The couple headed to Aberdeen, South Dakota, where the Orioles had a Single-A affiliate in the Northern League. The club was managed by Cal Ripken Sr., and featured several future major leaguers, including Mark Belanger and Lou Piniella. Aberdeen ran away with the league pennant, while Palmer finished 11-3 with a 2.51 earned-run average, throwing a no-hitter in June. He battled control problems—130 walks in 129 innings—but otherwise kept the opponents off the bases.

The Orioles had seen enough, and the 19-year-old Palmer made the big club out of spring training in 1965. The team had a lot of young pitching talent, and Palmer was mainly used as an emergency starter (six starts) and mop-up reliever, finishing 5-4 with a 3.72 ERA in 92 innings. He later recalled learning a lot that season from his roommate, Robin Roberts, the former Phillies star pitcher what was near the end of his career. Palmer’s first major-league victory came in relief on May 16, 1965, against the Yankees. In the same outing he hit his first home run, a two-run shot off Jim Bouton.

The next season, Palmer had a great spring and made the starting rotation. In the season’s second game, in Boston, he took a three-hit shutout into the ninth inning, and settled for a 5-1 victory and his first complete game. His best pitch throughout his career was a high fastball, though his first major-league manager, Hank Bauer, told him he couldn’t win throwing high. Even by 1966 there were opponents who were impressed. “I think he’s the hardest thrower in the league,” said Bill Skowron, veteran White Sox first baseman.2

For the 1966 season, Palmer finished 15-10 with a 3.46 ERA in 30 starts, leading a deep Baltimore staff in victories. The Orioles won the American League pennant, with Palmer winning the clincher with a five-hitter in Kansas City on September 22. He drew the Game Two World Series start in Dodger Stadium against Sandy Koufax, and the 20-year-old Palmer came through with a 6-0 four-hitter, besting Koufax in his final career appearance, and the Orioles went on to a 4-0 series sweep. It was during this season that Palmer earned the nickname Cakes for his habit of always eating pancakes on the morning of his starts.

Although Palmer seemed on the fast track to stardom, his career hit its biggest obstacle the next season. In fact, Palmer later recalled feeling arm soreness in the 1966 World Series. He began the 1967 season well and threw a one-hit masterpiece in Yankee Stadium on May 12: A single by Horace Clarke leading off the seventh was the only hit, and Clarke was quickly erased on a double play. Unfortunately, Palmer’s shoulder stiffened up in this very game, and after lasting only one inning in his next start, he soon found himself in the minor leagues. He pitched seven games for Miami and Rochester before making it back to the Orioles for two starts in September. He finished 3-1, 2.94 for Baltimore, but with an aching shoulder and back. Palmer later believed that his injury started as bicep tendinitis, but his favoring of the arm led to a torn rotator cuff in his shoulder.3

The 1968 season was another lost year for Palmer—he started ten total games for Miami, Elmira, and Rochester, losing his only two decisions and throwing just 37 innings. He never made it to Baltimore, and was so distressed that he considered attempting a comeback as a position player. Palmer was placed on waivers late in the season, and was not protected in that fall’s expansion draft to stock the new teams in Seattle and Kansas City. He went unselected, and many feared his career had come to an end.

The Orioles did not believe in pampering sore arms. George Bamberger, the Orioles pitching coach, wanted his charges to pitch through soreness until it was determined that the injury required surgery. Accordingly, Palmer pitched in the Florida Instructional League in the fall, then for the Santurce Crabbers (managed by Frank Robinson) in the Puerto Rican Winter League. Just as Bamberger had hoped, in Puerto Rico Palmer’s pain suddenly went away. He showed up at spring training to give it another shot. “It was a miracle as far as I was concerned,” recalled Palmer. “Like getting a new toy.”4

In mid-1968, while Palmer was in the minor leagues, the Orioles hired a new manager, Earl Weaver, with whom Palmer would publicly battle over the next 14 seasons. Weaver loved Palmer the pitcher, however, and a good spring got Palmer a start in the fifth game of the 1969 season. He responded with a five-hit shutout of the Senators, striking out slugger Frank Howard four times. “I think I’m back in business,” Palmer said.5 By the end of June he was 9-2 with a 1.96 ERA; his two losses were 2-0 to Denny McLain and 1-0 to Joel Horlen. He soon returned to the disabled list with a torn muscle in his lower back, missing six weeks of action, but in the second start after his return he pitched a no-hitter against Oakland, walking six but coasting to the 8-0 win. He finished the season 16-4, and his six shutouts and 2.34 ERA were both second best in the league. He easily defeated the Twins in the third game of the playoffs (11-2) to complete a Baltimore sweep, but lost to the Mets’ Gary Gentry in Game Three of the World Series, and watched New York go on to its historic five-game upset.

Palmer’s arm troubles were mostly over, and over the next nine seasons he won 20 or more games eight times and captured three Cy Young Awards. In fact, it is hard to separate Palmer’s outstanding seasons, as the honors and league-leading seasons piled up. During the Orioles’ great run of pennants (1969 to 1971) he was often considered the third starter on the team, behind Dave McNally (who won 65 games in the three seasons) and Mike Cuellar (who won 67), and Palmer pitched the third game in the playoffs in all three seasons. In reality, other than the missed time Palmer had in 1969 he was generally the team’s best pitcher, leading the Orioles’ great starting staffs in ERA every year between 1969 and 1973, and again between 1975 and 1978—nine times in ten seasons.

Although Palmer and Weaver had many public disagreements, about pitching, where the fielders should play, whether the team should bunt, many observers felt that they were made for each other. Paul Blair, the club’s center fielder, felt that the young Palmer would not want to stay in the game if he didn’t have his best stuff, and would come up with a twinge in his arm or something. While Hank Bauer would take him out of the game in these situations, Weaver would not. “So Palmer learned to get his fastball over, his curveball over,” recalled Blair, “and he learned to pitch because he was going nine. Earl made him grow up a little bit.”6

In 1970 Palmer finished 20-10 with a 2.71 ERA, leading the league with 305 innings pitched and five shutouts. Weaver employed a four-man rotation, and Palmer made 39 starts and completed 17 of them. In Game Three of the playoffs he dominated the Twins on a seven-hitter, also racking up 12 strikeouts as the Orioles completed a three-game sweep. In the World Series, against the Cincinnati Reds, Weaver switched up and gave Palmer the Game One start—he fell behind 3-0 early but the Orioles scraped out a 4-3 win for him. He came back in Game Four with a chance to sweep the Reds, and it looked for most of the game that he would succeed. The Orioles led 5-3 going into the eighth inning. After Palmer walked Tony Perez and allowed a single to Johnny Bench, Weaver brought in Eddie Watt to face Lee May. The Reds slugger promptly belted a home run, giving the Reds a 6-5 lead that would hold up. The Orioles won the Series the next day instead.

Palmer and the Orioles stormed back in 1971, this time highlighted by a pitching staff that featured a remarkable four 20-game winners (Palmer, Cuellar, McNally, and the newly acquired Pat Dobson). Palmer was the fourth to do it, with a 5-0 three-hitter over the Cleveland Indians on September 26. He went on to beat the Oakland Athletics in the playoffs to complete a series sweep for the Orioles, allowing three solo home runs in a 5-3 victory. This marked the fourth time Palmer had clinched a pennant for the Orioles, doing so in the 1966 regular season and all three years since the playoff format began in 1969. He also defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates in Game Two of the World Series, 11-3, then watched the Pirates win three straight to take a 3-2 lead in games. Palmer pitched well in Game Six, leaving after nine innings tied 2-2 in a game the Orioles won. Unfortunately for the Orioles, the Pirates wrapped up the series the next day.

The Orioles juggernaut took a big step back in 1972, though Palmer kept up his excellent pitching: He finished 21-10 with a 2.07 ERA as the club dropped to third place. In 1973 he did it all again, upping his record to 22-10 with a league-leading 2.40 ERA and capturing his first Cy Young Award, helping the Orioles win another division title. Palmer pitched a five-hit shutout to start off the playoffs against the A’s, but was knocked out early in the Game Four, a game in which the Orioles rallied to keep the series alive. Alas, Oakland wrapped up the pennant the next day. By this time, Palmer had finally moved to the head of the class among Oriole pitchers, though he had been a great pitcher for years. “If you had to pick one guy to win a game,” recalled first baseman Boog Powell, “he was my guy. As much as I loved Mike Cuellar, as much as I loved Dave McNally and Pat Dobson … if I had one game to win, Palmer was on the mound for me.”7

Palmer suffered an off-season in 1974, plagued by a sore arm and poor team support on both offense and defense. His record was just 7-12, though his ERA of 3.27 was better than the league average. His sore arm kept him out of action for two months. The Orioles staged a big team comeback—they were in fourth place, eight games behind the Red Sox with a 63-65 record on August 28, but finished 28-6 and won the division easily. Palmer threw two shutouts in September to help the cause. In Game Three of the playoffs he lost to Catfish Hunter 1-0, allowing only a solo home run to Sal Bando, and the Orioles went down in four games.

Palmer put together what might have been best season in 1975, finishing 23-11 with a league-leading 10 shutouts and a 2.09 ERA. His next season he went 22-13, leading the league in wins and innings pitched. Though the Orioles finished second in each season, Palmer captured both Cy Young Awards, becoming the first American League pitcher to grab the honor three times. Palmer was the last star remaining from the great teams of the early 1970s, which gave him more stature to bicker with Weaver. The two men both had big egos, and, as much as Weaver liked to tell Palmer what pitches to throw, Palmer like to tell Weaver how to manage the game. “He was Mr. Perfection,” recalled Weaver. “It had to be perfect. When things don’t go right, you’ve got to accept it. He didn’t want to. But he was a good pitcher.” As for Palmer, the pitcher allowed: “The bottom line is we were out there trying to do the same thing.”8

Palmer put together what might have been best season in 1975, finishing 23-11 with a league-leading 10 shutouts and a 2.09 ERA. His next season he went 22-13, leading the league in wins and innings pitched. Though the Orioles finished second in each season, Palmer captured both Cy Young Awards, becoming the first American League pitcher to grab the honor three times. Palmer was the last star remaining from the great teams of the early 1970s, which gave him more stature to bicker with Weaver. The two men both had big egos, and, as much as Weaver liked to tell Palmer what pitches to throw, Palmer like to tell Weaver how to manage the game. “He was Mr. Perfection,” recalled Weaver. “It had to be perfect. When things don’t go right, you’ve got to accept it. He didn’t want to. But he was a good pitcher.” As for Palmer, the pitcher allowed: “The bottom line is we were out there trying to do the same thing.”8

Along with the fame he gathered from being one of baseball’s greatest pitchers year after year, Palmer also became a very visible model for Jockey underwear. About 1977, he took part in an ad campaign involving several other athletes, including fellow baseball stars Pete Rose and Steve Carlton, with each man depicted in various styles of underwear in magazine ads. Eventually Jockey built its campaign around Palmer only. Jockey sold a very popular poster of Palmer in a pair of small briefs, and the photogenic Palmer appeared in Jockey ads for 20 years. His face was also used to sell other products nationally and in the Baltimore area.

Meanwhile, the great seasons kept coming. His 20-11, 2.91 campaign in 1977 included league-leading totals of 39 starts, 22 complete games and 319 innings pitched. He did not win his third straight Cy Young Award, finishing a close second to Yankee relief pitcher Sparky Lyle. Palmer attained 20 wins for the eighth time in 1978—only Warren Spahn (13 times) and Lefty Grove (8 times) have matched this feat among post-1920 major-league pitchers. Palmer’s 21-12, 2.46 season was nothing more than a typical Palmer season. He was only 32 years old, but had racked up 215 lifetime victories against only 116 defeats.

The 1979 Orioles surprised many observers by winning 102 games and easily capturing their first division title in five years. Palmer started typically well, and was 6-2, 2.80 at the end of May. For the rest of the season, however, he battled arm soreness and was on the disabled list twice, limiting him to just 22 starts and a 10-6 final record. Palmer was no longer the best pitcher on the club, but a respected leader to several promising young hurlers like Mike Flanagan, Dennis Martinez, and Scott McGregor. His stature helped earn him the Game One start in the playoffs against the California Angels, and he pitched nine strong innings in a game the Orioles won 6-3 in the 10th. In Game Two of the World Series against the Pirates he pitched seven innings and left the game tied 2-2. In Game Six he lost 4-0 to John Candelaria, and the Orioles lost Game Seven the next day.

Palmer came back strong in 1980, finishing 16-10 for a Baltimore team that won 100 games but finished second to the Yankees. Palmer no longer had the durability of his big seasons, leading to more no-decision outings. The next season was marred by a 50-day player strike in midsummer, and Palmer never really got on track, winning just seven games.

After Palmer started poorly in 1982 (1-1 with a 6.84 ERA in five starts), General Manager Hank Peters let it be known to the press that Palmer no longer warranted a spot in the team’s rotation. Weaver disagreed, though he did briefly put Palmer in the bullpen (where he struggled for four more appearances). Weaver made it known that Palmer would turn it around, and once back in the rotation he did just that. In the four months encompassing June through September, Palmer made 24 starts and compiled a 13-1 record with a 2.24 ERA. Weaver had announced early in the season that 1982 would be his final season, and the Orioles spent most of the season seemingly out of contention, finding themselves seven games behind the Brewers in late August. As they had done so often during the Weaver years, the club got red hot in September (19-9) then beat the Brewers three straight games to tie them with one final game to go. The red-hot Palmer faced off against Don Sutton in the finale on October 4, but the Brewers prevailed, hitting three solo homers off Palmer and then pulling away against the bullpen, 10-2.

For the 1982 season Palmer finished 15-5 with a 3.13 ERA (third in the league). This marked the 10th time that he finished in the top five in earned-run average and earned the 36-year-old a second-place finish in the Cy Young balloting.

Jim started well in 1983, allowing no earned runs in either of his first two starts, but spent two long stretches of the season on the disabled list, ending the season 5-4 in just 11 starts. The Orioles returned to the postseason again, though Palmer did not play a large role in the pennant race or the playoffs. In his one postseason appearance, a relief effort in Game Three of the World Series against the Philadelphia Phillies, Palmer earned his fourth World Series victory; it made him the only pitcher in history to win World Series games in three different decades. His career postseason record was 8-3 with a 2.61 ERA in 17 games, 15 of them starts. His teams won three World Series titles in six tries.

Palmer again made the Orioles rotation in 1984, but after just three starts and two relief stints (0-3, 9.17 ERA) the Orioles gave him his release on May 17. Palmer believed he could still pitch and likely had offers from other teams but chose not to pursue them. He made news seven years later when he went to spring training with the Orioles to try a comeback but called it off after suffering a hamstring injury during an exhibition game.

Palmer remained visible and active after his retirement. He began working for ABC Sports while still an active player – providing color commentary during several postseasons and the 1981 World Series—and continued this work after he no longer played. He worked a total of five World Series and several All-Star Games for ABC, along with many other sporting events. After ABC lost its national baseball contract in 1989, Palmer became an announcer for the Orioles, a role he had performed for 37 years by 2025. He was a regular presence in documentaries about the game and the world of sports over the years. He published a book on pitching in 1975 (Pitching), an exercise book in 1987 (Jim Palmer’s Way to Fitness), and a humorous memoir largely focused on his relationship with manager Earl Weaver in 1996 (Together We Were Eleven Foot Nine).

Palmer’s number 22 was retired by the Orioles, and he was elected to their Hall of Fame in 1986. He made the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1990, overwhelmingly elected on his first try along with Joe Morgan. Their induction ceremony was rained out, and held the next day in a local high school.

Jim had two daughters (Jamie and Kelly) with his first wife, Susan, and in 2010 was married for the third time, to a woman also named Susan. While the Baltimore franchise had fallen on hard times in the new century, Palmer remained a link and a visible reminder of the club’s long period of success. He had conquered the fields of pitching, modeling, and broadcasting, and had shown no signs of slowing down.

Last revised: April 1, 2012

A version of this biography originally appeared in SABR’s “Pitching, Defense, and Three-Run Homers: The 1970 Baltimore Orioles” (University of Nebraska Press, 2012), edited by Mark Armour and Malcolm Allen.

Sources

Joel Cohen, Jim Palmer—Great Comeback Competitor (Putnam, 1978).

Jim Palmer, Together We Were Eleven Foot Nine (Andrews McMeel, 2006).

Notes

1 The Sporting News, July 27, 1963, 35.

2 Joel Cohen, Jim Palmer–Great Comeback Competitor (Putnam, 1978).

3 John Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards (Contemporary, 2001), 198.

4 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, 199.

5 Jack Zanger, “The Arm That Came Back,” Sport, August 1969.

6 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, 273.

7 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, 275.

8 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, 273-274.

Full Name

James Alvin Palmer

Born

October 15, 1945 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.