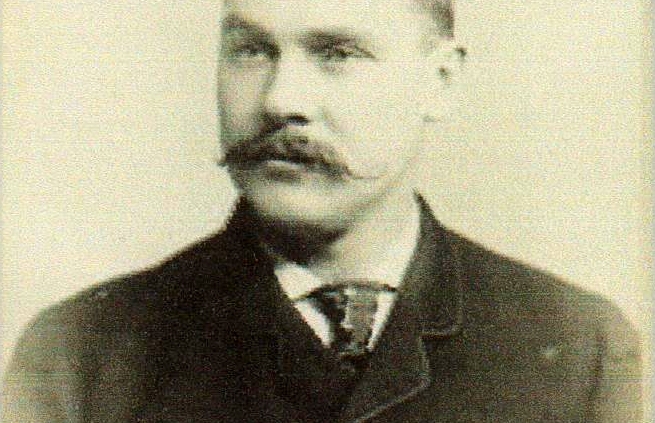

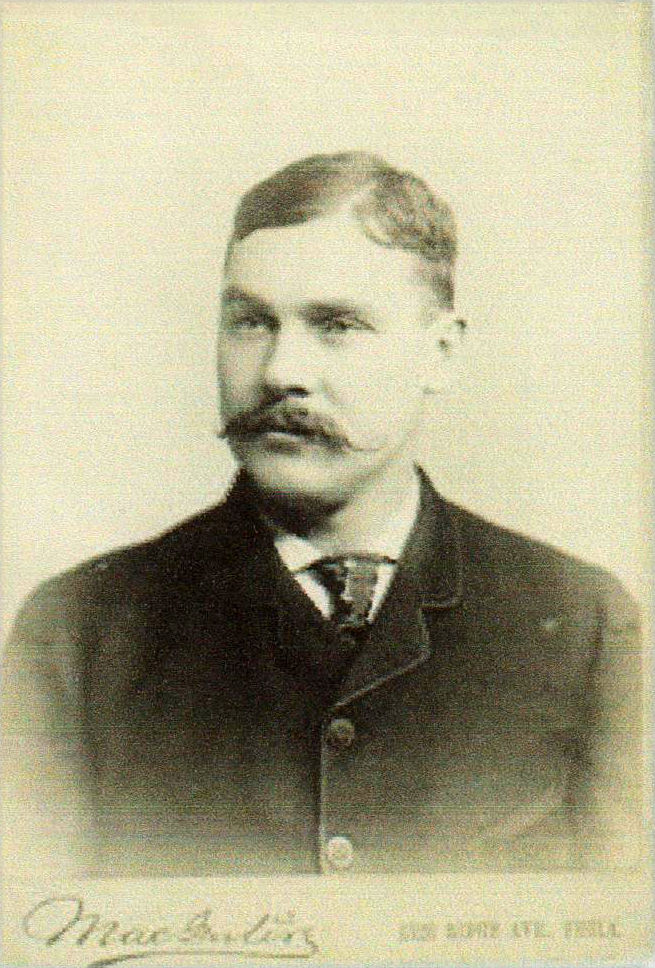

Andy Cusick

By late in the 1884 season, the amateur Fall River (Massachusetts) City League had placed five recent graduates in major league baseball. The star of this quintet was Charlie Buffinton, a right-handed pitcher then on his way to compiling numbers nearly worthy of the Hall of Fame. Fellow city league alumnus Frank Fennelly became a top-flight shortstop until a severely broken leg abruptly ended his career in the big leagues a few years later. Meanwhile, light-hitting infielder-outfielder Jimmy Manning and barehanded catcher Tom Gunning, while no more than journeymen major leaguers, distinguished themselves in other ways – Manning as a baseball executive and ball club owner; Gunning, a licensed physician, as a pathologist and longtime county medical examiner.

By late in the 1884 season, the amateur Fall River (Massachusetts) City League had placed five recent graduates in major league baseball. The star of this quintet was Charlie Buffinton, a right-handed pitcher then on his way to compiling numbers nearly worthy of the Hall of Fame. Fellow city league alumnus Frank Fennelly became a top-flight shortstop until a severely broken leg abruptly ended his career in the big leagues a few years later. Meanwhile, light-hitting infielder-outfielder Jimmy Manning and barehanded catcher Tom Gunning, while no more than journeymen major leaguers, distinguished themselves in other ways – Manning as a baseball executive and ball club owner; Gunning, a licensed physician, as a pathologist and longtime county medical examiner.

This profile focuses upon the last and least accomplished of the Fall River five: catcher-utilityman Andy Cusick. A teenage Irish Catholic immigrant, Cusick got a much later start on the game than the others, and his four-season major league career was a modest one. A decent receiver but weak batsman, he gave minor league umpiring a shot after his playing days were over. Thereafter, Cusick spent most of his working life as a Chicago police officer, eventually rising to the rank of district sergeant. Otherwise, he lived quietly with his wife, children, and extended family until his death in 1929. His story follows.

Andrew J. Cusick1 was born on an undetermined date in December 1857 in the centuries-old city of Limerick, a commercial hub situated in the middle-southwest of Ireland. He was one of at least four children born to common laborer John A. Cusick (1839-1913) and his wife Elizabeth (née Connor, 1840-1916). Nothing is known of our subject’s youth until mid-1875, when 17-year-old Andy emigrated with his parents and siblings to America. In time, the Cusick family settled in Fall River, a bustling mill town located about 30 miles south of Boston. There, Andy found employment as a plumber.

Fall River was also the place where Cusick was introduced to his new country’s emerging national pastime. The town hosted League Alliance and New England Association teams in 1877 and was a hotbed of 19th century amateur baseball. As such, it was a fertile spawning ground for talent, with prospects progressing from sandlot play to a highly competitive city league.2

Cusick (who batted and threw righthanded) was well-built (5-foot-9½; 190 pounds)3 and tough-minded. These attributes helped make up for his belated initiation into the game – he gravitated toward catcher, the most physically taxing position on the diamond. Protected by only a primitive face mask and receiving barehanded, Cusick would be beset by finger and thumb injuries as well as the other debilities that came with playing behind the bat in the 1880s. Natural athleticism, however, made Cusick versatile, allowing him to fill in at any position (except pitcher) when he needed time off from catching duties.

Cusick’s name first made newsprint in August 1881 when his defensive work, and that of shortstop Frank Fennelly, was cited as the highlight of Fall River’s play in an 8-1 defeat at the hands of the Flints and its battery of Charlie Buffinton and Tom Gunning.4 The following summer, second baseman Cusick, catcher Gunning, and shortstop Jimmy Manning supplied most of the Fall River offense in a 7-6 triumph over Taunton.5

Cusick entered the professional ranks over the winter, signing with the Wilmington (Delaware) Quicksteps of the independent Inter-State Association.6 In addition to contests against ISA rivals, the Quicksteps played a steady diet of games against National League, American Association, unaffiliated professional, and semipro clubs, and thus required an ample complement of backstops. Cusick, however, was the receiver usually paired with staff ace Charley Dorr. He also played the outfield on occasion.

Wilmington struggled out of the gate in ISA play, and by mid-June strife between manager Charlie Waitt and his charges was out in the open. Waitt proposed to remedy the problem by releasing Cusick, Dorr, and three others who clashed with him.7 But soon thereafter it was Waitt who got the gate. As the season continued, Cusick suffered finger and hand injuries on a regular basis; he was also put out of action briefly by a foul tip that creased his mask and put a nasty gash in his forehead. Notwithstanding the battering, his defensive work was regularly complimented in the local press. “Cusick played an excellent game behind the bat” during an 8-2 win over Trenton, observed the Wilmington Republican in early July.8 The following day, the Wilmington Gazette informed readers that catcher “Cusick played a splendid game” in a 4-3 loss to the Pottsville (Pennsylvania) Anthracites.9 And he played “a faultless game” behind the plate in a 12-0 drubbing of the Ross club of Chester, Pennsylvania, in September.10

His batting, alas, was another matter. In 47 ISA contests, Cusick posted a feeble (31-for-200) .155 batting average, with but two extra-base hits. And despite the glowing praise for his defensive work in the local press, his .860 fielding percentage placed him toward the bottom of the rankings for ISA catchers.11 Still, at season’s end Wilmington (24-49, .329) was quick to re-engage Cusick, signing him for the upcoming season.12 Sporting Life approved his retention, stating that “Andy Cusick … is no doubt one of the pluckiest catchers in the profession … [but] is only fair at the bat. Andy is a great favorite here [in Wilmington].”13 Cusick then returned to Fall River to resume his winter job as a plumber.

At this point, Cusick’s hometown mates were further along in their ballplaying careers, and all would be major leaguers in 1884. Charlie Buffington had won 25 games for the National League’s Boston Beaneaters during the 1883 campaign, and would be joined for the new season in Boston by Fall River friends Jimmy Manning and, in mid-July, Tom Gunning. Meanwhile, Frank Fennelly, the ISA leader in base hits, runs scored, and home runs, had signed with the Washington Statesmen of the major league American Association and would go on to have a standout rookie season.

Cusick’s route to the majors was more circuitous. While he was home in Fall River, the Quicksteps were being courted by the Union Association, an upstart major league in the making bankrolled by the well-heeled Henry V. Lucas of St. Louis.14 For the time being, however, Wilmington opted for a berth in a newly formed minor loop, the Eastern League. The star of the 1884 Quicksteps (and at $325/month its highest-salaried player) was right-handed pitcher Ed “The Only” Nolan. His regular batterymate was Andy Cusick ($150/month).15 Behind the pair, the Quicksteps dominated the competition, posting a scintillating 50-12 (.806) record into mid-August. Splitting his time between catching (31 games) and various infield-outfield positions (parts of 33 games), Cusick did his share, batting a respectable .242, with 10 extra-base hits and 66 runs scored, with excellent defensive work behind the plate.16

Unhappily for club backers, Eastern League games did not attract much attendance to the Wilmington ballpark. On August 12, the Quicksteps quit the circuit – but did not disband. Rather, a week later the club assumed major league status, entering the Union Association as a replacement for the recently defunct Philadelphia Keystones.17At first, it was reported that the Nolan-Cusick battery had abandoned Wilmington to sign with the Philadelphia Quakers of the National League.18 But after several anxious days in Wilmington, the two were induced to stay with the Quicksteps.19 Little good it did the club. That Wilmington was out of its depth in the Union Association was reflected in the 12-1 trouncing administered by the Washington Nationals on August 21, 1884 – Andy Cusick’s major league debut. He went 0-for-3 at the plate. Thereafter, he managed but five singles in his next 10 games, and was batting a paltry (5-for-34) .147 when Wilmington (2-16, .125) gave up play in mid-September.20

Although he had posted only a 1-4 record, Nolan had pitched well during his brief UA stint and was now a widely coveted free agent. But the willful hurler was not disposed to breaking in a new catcher; Nolan and Cusick had to be taken as a package. That was agreeable to Harry Wright, manager of the NL Quakers, who signed the two for his struggling Philadelphia club.21 Cusick hit National League pitching no better than he had UA offerings, registering only four singles in 29 at-bats for the Quakers. But his .930 fielding percentage was the best of the nine Philadelphia backstops who caught more than a single game, and Philadelphia reserved Cusick for the following season.22

The Quakers’ 56-54-1 (.509) record in 1885 represented a 27-game improvement in the win column over the previous season. But little of that advancement was attributable to the work of the Nolan-Cusick battery. The former, plagued by arm miseries, posted a disappointing 1-5 record in only seven appearances and was released at season’s end.23 Cusick, meanwhile, registered lackluster numbers on both offense and defense. His.177 batting average in 39 games (25-for-141) was about on par with that of fellow Philadelphia catchers Jack Clements (.191 BA in 52 games) and Charlie Ganzel (.168 BA in 34 games). But only one of his base hits took him past first base, and he struck out 24 times while drawing but one walk. And his backstopping – a whopping 57 errors against 180 putouts and 60 assists, with 34 passed balls – was decidedly inferior to that of the Quakers’ other receivers. In fact, on the basis of fielding percentage Cusick was the worst defensive catcher in the National League in 1885.24

Statistics, however, may not present the same picture of Cusick as that seen in person by his contemporaries. He evidently called a good game, and rookie right-hander Ed Daily (26-23, with a 2.21 ERA) blossomed with Cusick as his primary receiver. Whatever the basis, Philadelphia wanted Cusick back and reserved him for the 1886 season. Over the winter, however, it was reported that he would be released prior to spring training.25 As he awaited his fate, the year’s bright moment for Cusick occurred on October 21, 1885: marriage to Mary Callahan of Chicago, like himself an Irish Catholic immigrant. For much of the ensuing 44 years, the couple would make their home in the Windy City.

In March 1886, Philadelphia had an overabundance of catchers under contract, and Cusick’s roster prospects looked grim. But he reported to manager Wright in such excellent physical condition that the Philadelphia skipper decided to bring him south for an audition. Given the chance, Cusick impressed. He demonstrated “such good work and has shown such marked improvement, both in batting and fielding, over last season that he will be kept as a regular member of the team.”26

Once the regular season began, Philadelphia, by then more often called the Phillies, continued on the upswing, eventually finishing 71-43-5 (.623). But that handsome mark was good only for fourth place, well behind the NL champion Chicago White Stockings (90-34, 726). For most of the season, Cusick was the third man in a catching troika behind Clements (.205 in 54 games) and Deacon McGuire (.198 in 50 games). Cusick outhit the other two (.221 in 29 games) but showed little power, with only six extra-base hits and four RBIs in 104 at-bats. His receiving stats (120-35-19 = .891 FA, with 21 passed balls) were comparable to those of Clements and McGuire and much improved over his previous season’s work.27 As a result, this time it came as no great surprise when Philadelphia reserved Cusick for the 1887 season.28

From the previous year’s experience, Cusick knew that being on the club’s reserve list did not guarantee him a roster spot. He was also prone to in-season weight gain. Thus, to enhance his chances, after the season ended he “lost 30 pounds of flesh”29 via winter workouts with Charlie Buffinton and Tom Gunning at the Fall River ice skating rink.30 Cusick, however, was not the only beneficiary of these sessions. Plagued by shoulder problems, Buffinton had pitched poorly (7-10, 4.59 ERA) in Boston the previous year. (He had also antagonized Beaneaters club boss Arthur Soden with union activism.) Largely based on assurances by Cusick that Buffinton’s arm was sound, Philadelphia purchased the contract of his available Fall River friend at the bargain price of $500.31 The inclusion of catcher Gunning in the deal, however, created a new threat to Cusick’s own future with the Phillies.32

Sure enough, Gunning quickly supplanted Cusick as Philadelphia’s third catcher. But for the time being, his versatility – veteran infielder Arthur Irwin considered “the portly Andy as good a first baseman as there is in the business”33 – secured Cusick a roster spot. He saw little game action, however, and was advertised as available for purchase by other clubs, but without takers.34 In the meantime, Cusick was put to use as emergency umpire in a late-May Detroit vs. Philadelphia contest and “gave universal satisfaction.”35 Thus, a new career avenue was opened.

Disaffected by his lack of playing time, Cusick went AWOL in mid-July and was promptly suspended by the club.36 But he was just as quickly reinstated when hand injuries left Jack Clements and Tom Gunning unable to catch.37 Whether rusty or out of shape, Cusick’s performance behind the plate was atrocious. In four games, he committed 10 errors and permitted six passed balls. As a three-game fill-in at first base, however, he handled 28 chances without a miscue.38 And in limited at-bats, Cusick even hit a bit (7-for-24, .292). Nevertheless, the Phillies had little need of Cusick and gave him notice of his release in late August.39 Before he took his leave, Cusick was again pressed into service as a game arbiter and “umpired very satisfactorily” during a 4-1 Philadelphia win over Pittsburgh.40 Whether a direct result of this performance or not, it was reported that Phillies manager Wright had recommended that Cusick be chosen to fill the first vacancy in National League umpiring ranks.41

His release by Philadelphia brought the major league playing career of Andy Cusick to an end. Over four seasons, he appeared in 95 games, batting a tepid .193 (64-for-332), with little extra-base power (one triple, no home runs, .220 slugging percentage). Except for first base, his defense had also been substandard, with 100 errors and 95 passed balls in only 82 games behind the plate, and five misplays in six games as an infielder.

Still, there remained interest in Cusick’s services, albeit confined to the minor league level. Over the winter, he was signed as a first baseman by the Milwaukee Brewers of the Western Association.42 In spring 1888, however, Cusick reported to Milwaukee “in poor condition.”43 He was released in mid-July after having hit .260 in 48 games.44

Almost immediately thereafter, he was hired as an umpire by the Western Association and finished out the season wearing blue. Of interest, the WA crown was captured by the Kansas City Blues, a club captained, managed, and owned by another of Cusick’s Fall River friends, Jimmy Manning.45

Although his umpiring had not been well received in certain league venues – it was even feared that Sioux City would refuse to play if Cusick were assigned to umpire its games – the Western Association reengaged him for the 1889 season.46 This time, the censure of his work was near universal, with the Omaha Bee denouncing Cusick’s umpiring of a Omaha-Denver game in late May as “the vilest ever seen on the home grounds.”47 Days later, the Milwaukee Journal took a critical, but more measured, view of Cusick’s work. “Andy Cusick, who umpired, gave some very doubtful decisions on both sides and was especially incorrect on calling balls and strikes,” the newspaper opined after Omaha defeated Milwaukee, 8-7.48 In mid-June, he was a no-show for a game in St. Paul.49 Thereafter, Cusick’s name disappeared from WA box scores.

During the ensuing winter, it was reported that Cusick was “working at his old trade, plumbing,” in Omaha and lending his support to the Players League movement.50 He was also said to be trying to get back into the game as either a first baseman or umpire in the Texas League.51 A month later, the Omaha Bee reported that “Andy Cusick … a ballplayer” had been arrested for brawling at a local saloon.52 But follow-up reportage suggests that our subject had been confused with a former ballplayer named Dan Cusick.53 In any event, Andy was re-hired when the Western Association needed replacement umpires that June.54 But his work was no better received around the circuit than it had been the season before. He was sacked in August, supposedly because “he looked upon the wine while it was red during his last visit to Kansas City.”55 If credible, it is the only discovered news report of Cusick having an alcohol-related problem during his baseball years. Whether true or not, Cusick was back in harness and umpiring WA games at season’s end.56

From this point on, our subject’s whereabouts and activities become commingled with those of others with the surname Cusick. It is, for example, difficult to reconcile a January 1891 Sporting News report that “Andy Cusick is now a deputy constable in St. Louis”57 with government records that make him a resident of Chicago at that time.58 Likewise, the December 1892 birth of a son in Chicago, the first of Andy and Mary Cusick’s five children, makes it improbable that our subject was the “Dan Cusick” arrested for rigging downstate boxing matches in February 189359 or getting into further scrapes with the law in St. Louis.60

Sometime during the 1890s, Andy Cusick became a member of the Chicago Police Department. By the time of the 1900 US Census, he was the head of a household that included a wife, three young children, both his parents, and various in-laws. The Cusick brood had grown to five by 1910.61 By the time of his retirement from the force in the early 1920s, he had risen to the rank of district sergeant.62 His beat, however, must have been a quiet one, for a newspaper search for mention of Sergeant Cusick’s exploits came up empty.

Andrew J. Cusick died in Chicago on August 6, 1929. He was 71. Following a Funeral Mass said at St. Felicitas Church, his remains were interred at Mount Olivet Cemetery, Chicago. He was survived by his widow Mary; children Daniel, Elizabeth, Andrew, Kathlyn, and Charles; and three siblings.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info imparted above include the Andy Cusick file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; the Cusick profile in Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 1: The Ballplayers Who Built the Game, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2011); US Census and other government records accessed vis Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Andrew J. Cusick is the birth name given to our subject by modern baseball authority. Find-A-Grave and other general reference works sometimes give his birth name as Andrew Daniel Cusick. So does David Nemec’s The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball (New York: David I. Fine, 1997). No original source for either birth name was discovered by the writer during research for this profile. Rather, Cusick’s name in contemporaneously published newsprint and government records appeared without middle name or initial. The putative nickname Tony sometimes listed for Cusick is specious. During his lifetime, he was always known as Andy Cusick.

2 As with previous profiles of Charlie Buffinton, Tom Gunning, Frank Fennelly, and Jimmy Manning, the writer is indebted to Fall River historian Philip J. Silvia for generously supplying background information and archival material regarding 19th century baseball in Fall River.

3 Per Sporting Life, February 15, 1888: 5. Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet list Cusick as one-half inch shorter.

4 See “Sporting Summary,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Herald, August 8, 1881: 4.

5 See “Sporting News,” Fall River Herald, August 21, 1882: 4.

6 As reported in the Fall River (Massachusetts) Evening News, December 26, 1882: 2.

7 As reported in “Quickstep Troubles,” Wilmington (Delaware) Gazette, June 25, 1883: 1.

8 “Base Ball,” Wilmington (Delaware) Republican, July 5, 1883: 1.

9 “The Anthracite Game,” Wilmington Republican, July 6, 1883: 1.

10 See “Chester Pets Laid Out,” Wilmington Republican, September 11, 1883: 3.

11 Per ISA defensive stats published in Sporting Life, November 14, 1883: 2. Cusick’s fielding average ranked 15th among ISA receivers.

12 Per “Notes,” Wilmington Gazette, October 22, 1883: 1. See also, “Players of the New Quicksteps,” (Wilmington) Morning News, November 15, 1883: 4.

13 “Wilmington’s Pets,” Sporting Life, January 1, 1884: 2.

14 See again, “Players of the New Quicksteps,” above.

15 Per Wilmington Quicksteps player salaries published in the Wilmington Republican, September 16, 1884: 1.

16 After the season, the Nolan-Cusick combo was named the Eastern League’s best fielding battery by Sporting Life, December 3, 1884: 3. Cusick also played third base, shortstop, and the outfield for the EL edition of the Wilmington club.

17 See “Gone to the Unions,” Morning News, August 19, 1884: 4.

18 Same as above.

19 As reported in “From Wilmington,” Sporting Life, August 27, 1884: 3; “The Cleveland Here,” Trenton Evening Times, August 25, 1884: 1. See also, the Washington (DC) National Republican, August 23, 1884: 3, and Wilmington Republican, August 23, 1884: 4.

20 See “One Ball Club Less,” Morning News, September 16, 1884: 1; “At Last! At Last!” Wilmington Republican, September 16, 1884: 1.

21 As reported in “Diamond Siftings,” Boston Herald, September 19, 1884: 2; and elsewhere.

22 Per “The League Reserves,” Boston Herald, October 22, 1884: 1.

23 As reported in “Base Ball Notes,” Cleveland Leader, October 27, 1885: 3.

24 As expressly noted in the Cleveland Leader, October 27, 1885: 3; and (Springfield) Illinois State Journal, October 18, 1885: 2. Cusick’s 57 errors were the most committed by a National League catcher in 1885.

25 See e.g., “The Ball Players,” Philadelphia Times, March 14, 1886: 6.

26 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Times, April 3, 1886: 2.

27 Baseball-Reference lists Cusick as also playing for the Milwaukee Brewers of the Northwestern League during the 1886 season. This is mistaken, perhaps resulting from confusion of our subject for Milwaukee’s Opening Day pitcher. Milwaukee baseball historian Dennis Pajot identifies the pitcher as John Cusick, a local product. See The Sporting News, May 17, 1886: 3. In any case, Andy Cusick spent the entire 1886 season as a member of the Philadelphia Phillies.

28 As reported in the Evansville (Indiana) Courier, October 14, 1886: 1; St. Paul Globe, October 14, 1886: 2; and elsewhere.

29 Per “Sporting Splints,” Saginaw (Michigan) News, January 15, 1887: 3.

30 Per Sporting Life, April 6, 1887: 1. See also, “City Briefs,” Fall River Herald, February 28, 1887: 4.

31 As reported in “Buffinton and Gunning Go to Philadelphia,” Sporting Life, April 6, 1887: 1; “Philadelphia’s New Battery,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 5, 1887: 4; and elsewhere.

32 See “Base Ball,” Fall River Evening News, April 14, 1887: 2, citing the Philadelphia Record.

33 “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, June 1, 1887: 4.

34 See e.g., “Base-Ball Notes,” Indianapolis Journal, June 24, 1887: 4, revealing Pittsburgh’s rejection of a Philadelphia sale proposal involving Cusick. A report that Cusick had been released to Washington proved unfounded.

35 Per the Saginaw News, May 20, 1887: 3, reporting on a 16-5 Detroit triumph.

36 See “Base-Ball Notes,” Indianapolis Journal, July 20, 1887: 4.

37 Per “Good for the Phillies,” Philadelphia Times, July 19, 1887: 4; “Dust from the Diamond,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, July 18, 1887: 1.

38 Spelling injured first sacker Sid Farrar, “big, fat Cusick played first base in brilliant style” during an 8-0 Phillies win over Washington. See “Washington Shut Out,” Philadelphia Times, August 15, 1886: 2.

39 As reported in the Boston Herald, August 26, 1887: 5; Indianapolis Journal, August 23, 1887: 4; and elsewhere.

40 Per the Worcester Spy, August 31, 1887: 4.

41 Per “Base Ball,” Fall River Evening News, August 29, 1887: 2.

42 As reported in the St. Paul Globe, December 30, 1887: 6; Sporting Life, December 21, 1887: 1; and elsewhere.

43 According to Milwaukee “Manager Hart Writes about His Players,” Sporting Life, May 2, 1888: 1.

44 Per “Blakely Does ‘Em,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 19, 1888: 4.

45 Manning also led the Western Association in runs scored (123) and stolen bases (101).

46 Per St. Paul Globe, May 10, 1889: 2.

47 See “Took Two Out of Three,” Omaha Bee, May 28, 1889: 3. Days later Omaha club president J.C. McCormick informed Western Association officials that Cusick would no longer be permitted to “umpire any more games on Omaha grounds,” per “Cusick Goes,” (Denver) Rocky Mountain News, June 1, 1889: 3.

48 “General Sporting Notes,” Milwaukee Journal, June 3, 1889: 1.

49 See “Won in the Seventh,” St. Paul Globe, June 17, 1889: 2.

50 See “Gate City Gossip,” Sporting Life, January 22, 1890: 1.

51 Per “Texas League,” Sporting Life, January 29, 1890: 7.

52 See “Jailed for Fighting,” Omaha Bee, February 19, 1890: 1.

53 See e.g., “Dan Cusick Charged with Larceny,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 16, 1891: 9. See also, “Notes and Siftings,” Sporting Life, January 16, 1892: 3.

54 See “Notes and Gossip,” Sporting Life, June 21, 1890: 4; “Leach and Blogg Released,” Omaha World-Herald, June 13, 1890: 2.

55 See “The Selection of Umpires,” Bode (Iowa) Republican, August 29, 1890: 1; “Sporting Gossip,” Kansas City Times, August 16, 1890: 2.

56 As reflected in September 1890 Western Association box scores published in Sporting Life and elsewhere. His work during a late-season doubleheader between Omaha and Kansas City was described as “impartially bad.” See “They Won the Game Twice,” Omaha World-Herald, September 1, 1890: 2.

57 See “Notes and Comment,” Sporting Life, January 10, 1891: 2. See also, “News, Gossip, and Editorial Comment,” Sporting Life, December 27, 1890: 5.

58 The 1890 US Census has been lost, but State of Illinois voting records accessible on-line list Cusick as a Chicago resident since November 1890.

59 See “Arrests in the Madison Prize Fight,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, February 11, 1893: 7. Although the charge is preferred against Andy by 19th century baseball scholar David Nemec in Volume 1 of Major League Player Profiles, 1871-1900, 228, the accused in this matter was identified as one Daniel Cusick in contemporaneous newsprint. See “Prize Fighters Under Arrest,” Edwardsville (Illinois) Intelligencer, February 15, 1893: 1.

60 See e.g., “Dan Cusick Discharged,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 30, 1892: 6; “Minor Mention,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 27, 1892: 3.

61 Per the 1910 US Census.

62 As noted years later in the obituary of his wife. See “Mrs. Mary Cusick,” Chicago Tribune, October 9, 1945: 24.

Full Name

Andrew J. Cusick

Born

December , 1857 at Limerick, (Ireland)

Died

August 6, 1929 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.