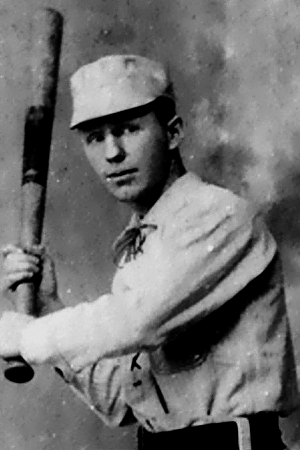

Paul Radford

Overcoming the physical obstacle of often being his team’s smallest ballplayer, Paul Radford played in 1,361 games for nine different teams during a 12-year major-league career that spanned 1883 to 1894. A biography written at the end of his career summarized how that the 5-foot-6, 150-pound Radford was able to survive so long in the major leagues: “While he did not excel in either batting, base running or fielding, he certainly ranked high in all when taken together, and his reputation has been solidly built, and is thoroughly established by reliable, honest and earnest work.”1

Overcoming the physical obstacle of often being his team’s smallest ballplayer, Paul Radford played in 1,361 games for nine different teams during a 12-year major-league career that spanned 1883 to 1894. A biography written at the end of his career summarized how that the 5-foot-6, 150-pound Radford was able to survive so long in the major leagues: “While he did not excel in either batting, base running or fielding, he certainly ranked high in all when taken together, and his reputation has been solidly built, and is thoroughly established by reliable, honest and earnest work.”1

Another obstacle, less well known, hampered the diminutive Radford’s longevity in professional baseball: he was a Sabbatarian, i.e., a person who strictly observes Sunday as a day of rest, which caused him to refuse to play in Sunday ballgames. Radford was one of the few Sabbatarians in the history of major-league baseball, who notably included Hall of Famers Christy Mathewson and Branch Rickey.2

Paul Revere Radford was born on October 14, 1861, in Roxbury, Massachusetts, the son of Benjamin and Anna (Hale) Radford.3 Paul was the youngest of their four sons who survived to maturity (six other children died in childhood).4 In 1865 the Radford family relocated to the town of Hyde Park, where his father worked as superintendent of construction at the American Tool and Machine Company.5 Paul grew up in suburban Hyde Park, a streetcar suburb 10 miles southwest of Boston, amid middle-class prosperity in a house on Fairmount Avenue, as his father advanced to general manager at American Tool.6

As part of the Radford middle-class lifestyle, Paul was a student through age 20, but the details, including college affiliation, remain elusive.7 A brief 1883 biography remarked about his education only that “during his school days the study he loved best was base ball,” and then focused on his three years playing for the amateur Hyde Park Base Ball Club from 1880 to 1882.8 During this period he had very few opportunities to play professional baseball. Beyond the Boston, Worcester, and Providence clubs in the National League, there were no longer any New England-based teams in an organized professional baseball league, as the region’s nascent minor leagues of the 1870s had all collapsed by 1880.9

The Radfords’ lifestyle also imbued in Paul the Sabbatarian belief that no activity was permitted on Sunday other than attending services at the local Methodist church.10 The Methodist denomination was one of the strongest proponents of Sabbatarian belief in the nineteenth century.11 The Hyde Park team played no ballgames on Sunday. Massachusetts then had a strict Sunday law, which prohibited not only “work, labor, or business” but also “any sport, game, or play,” with fines for the latter meted out to both participants and spectators.12

In 1882 the Hyde Park team, with Radford alternating between pitcher and outfielder, played two dozen games against the best amateur teams in eastern Massachusetts. Many of the team’s games were reported in the Boston Globe, including two exhibition games at the South End Grounds against the Boston club of the National League.13 His performance in those two games convinced Boston to sign him for the 1883 season to be an outfielder and change-pitcher.14 The role of change-pitcher was important at the time, as no substitutes were then allowed to the starting nine players (unless a player was injured and the opponent approved the substitution), so a position player who could also pitch in a pinch was a valuable man. This was the primary early rationale for Radford’s existence in professional baseball.

Radford was the regular right fielder for Boston in 1883, even though he didn’t distinguish himself as a hitter, as he compiled a lowly .205 batting average. He never pitched in a regular-season game that season. However, because Boston won the National League pennant in 1883, Radford was considered to be a lucky mascot. He achieved this reputation early in the season by finding a discarded horseshoe that was stamped “O. Winn,” the shoe’s manufacturer (Owen Winn).15 When Boston won 11 of its next 13 games to move above .500, and 15 of the following 20 games to attain first place, the superstitious Boston players took the stamping on the horseshoe to have meant “win” ballgames and thus anointed Radford as the team’s lucky charm. Since the owners of the Boston club were not nearly as superstitious as its players, though, Radford was released in November 1883.16

For the 1884 season Radford took his lucky horseshoe to Providence, which signed him to serve as right fielder and change-pitcher.17 His fortuitous image as “the mascot of the base ball profession” was reinforced when Providence won the National League pennant in 1884.18 Once again Radford was a dismal hitter, with a .197 batting average, and in the two games he pitched was ineffective, with a 0-2 record. In October 1884 Providence won the inaugural World Series against the New York Metropolitans of the rival American Association. Radford, who went hitless in the Series, is best remembered today as a member of the first World Series championship team.

Providence retained Radford’s services for the 1885 season, the only time during his first 10 years in major-league baseball that he played two consecutive seasons for the same club. However, his luck as a talisman ran out as he could not deliver a third consecutive league championship. After the 1885 season, Radford gave his lucky horseshoe to the Boston club, which hung it in the rear of the grandstand at the South End Grounds.19

Although he pitched in three games for Providence in 1885 (two starts and one relief appearance), Radford’s value as a change-pitcher was now diminished. Clubs had expanded their pitching staffs from two men to three or more to handle the lengthened regular-season playing schedules of the 1880s. There was now less demand for a position player to serve as an emergency pitcher to replace a tired starting pitcher; the need for a change-pitcher would evaporate in 1889 when the free substitution rule was first established to allow a reserve player on the bench to enter the game to replace a starting player.

During the mid-1880s the primary reason Radford remained in the major leagues was that “the little fellow can cover ground better than any right-fielder.”20 Radford was such a student of the right-field position that he authored the “On Right Fielding” section of an 1889 book about how to play baseball. Radford considered right field to be the most challenging of the three outfield positions. “A large portion of balls going to right field from right-handed batsmen … curve toward the foul line, besides having a twist,” Radford wrote, adding that (in this no-glove era) these hits were “hard to judge, and even if judged correctly, difficult to hold, as such balls have a way of getting through a fielder’s hands.”21 The right fielder also was the only outfielder with a chance of throwing out a batter at first base, a common event in the 1880s. “It is no easy matter to judge a ground ball while running speedily,” Radford wrote, “and it is also difficult to instantly throw the ball true and hard after one has got hold of it.”22

Radford’s Sabbatarian beliefs were never a problem when he played for Boston or Providence, since the National League during the 1880s expressly prohibited Sunday games. However, he soon had to confront the possibility that Sunday baseball would impact his baseball career, when he would need to demonstrate additional skills to offset his absence from Sunday games.

On October 21, 1885, Radford married Mary Blair, who was known as Minnie.23 The wedding ceremony took place at her brother-in-law’s home in Cambridge, just north of Boston, and was performed by Rev. Tilden of the Baptist church in Hyde Park.24 It is unclear whether Radford converted to the Baptist faith (another bastion of Sabbatarian belief) or continued to worship the Methodist faith. For the next five years, the Radfords made their offseason home in Cambridge with her sister and brother-in-law, while they lived during the baseball season in the city for which Paul played baseball.25

After Providence was expelled from the National League, the new Kansas City franchise acquired Radford’s services for the 1886 season.26 Kansas City was the first stop of a six-year baseball odyssey, when he played just a single year for six different clubs from 1886 through 1891. Radford was the regular right fielder for Kansas City, but he also played 30 games at shortstop, to expand his repertoire of fielding skills on the diamond. He also worked to be a more frequent baserunner, by drawing 58 walks in 1886 (the same number he had in 1884 and 1885 combined), and to be an aggressive baserunner, by stealing 39 bases in 1886.

In October 1886 Radford glimpsed the future testing of his Sabbatarian beliefs when he had to refrain from playing in a postseason exhibition game that Kansas City played on Sunday in Denver.27 In March 1887 the Kansas City club left the National League, after just one season, to play in a minor league that permitted Sunday games. In the dispersal of the Kansas City players, when no National League team expressed an interest in Radford, the New York Metropolitans of the American Association acquired his services for the 1887 season.28

With the Metropolitans, Paul’s Sabbatarian beliefs became an issue for the first time in his baseball career, since the American Association allowed Sunday games where legally permissible. While it was “distinctly stated in his contract that he was not to be called upon to take part in any game played on Sunday,” Radford probably had to accept a lower salary in exchange for this contractual provision.29 He missed all 10 Sunday games played by the Metropolitans in 1887, since, as the New York Times noted, “Radford never takes part in Sunday games.”30

Radford mostly played infield for the Metropolitans (76 games at shortstop, 18 at second base), with less time in the outfield (37 games), and two relief appearances as a pitcher. He also took advantage of a rule change for 1887 that characterized walks as base hits to enhance his value to the club and partially counteract his Sunday absences and his weak hitting. With a league-leading 106 walks, Radford posted a .404 batting average that season, good for seventh highest in the league.31 His adjusted figure in today’s records, not counting walks as hits, is a mediocre .265 average. However, this one season ostensibly as a .400 hitter was the focus of his nationally distributed Associated Press obituary in 1945, which misleadingly termed Radford as “one of baseball’s old-time great batters.”32

When the Metropolitan club went out of business after the 1887 season, the Brooklyn club acquired all of its ballplayers, including Radford, for the 1888 season.33 His Sabbatarian beliefs were now a bigger concern, however, since the Brooklyn club played every Sunday during the 1888 season, 19 Sunday home games (when the club played at isolated Ridgewood Park in Sunday-baseball-tolerant Queens) and seven Sunday road games in the Western cities.34 By being absent on the 26 Sunday dates, Radford missed nearly 20 percent of Brooklyn’s games in 1888.

Minnie Radford was often seen at the Brooklyn ballpark during the 1888 season. “Among the most graceful tricycle riders in the city is Mrs. Paul Radford, the wife of the center fielder of the Brooklyn Club,” the Brooklyn Eagle noted. “She is also a very correct scorer of the game, and has a complete record of all of her husband’s fine work in the field.”35

Prior to the 1889 season, because the Brooklyn club wanted an everyday outfielder, Radford was released “on account of his inability to play on Sunday.”36 He caught on with the Cleveland club, which transferred for the 1889 season from the American Association to the National League, where Sunday baseball issues would not impact Paul’s services.37 Playing in 136 games as an outfielder, Radford had his most productive National League season with a .238 batting average in 1889.

For the 1890 season, Radford, like many National League players, jumped to the Players League, established by the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players due to its squabbles with the National League club owners. Playing with the Cleveland club in the new league, Radford played free of Sunday baseball issues for a second consecutive year, since the Players League did not allow Sunday games.

Radford had his most productive hitting season in 1890, compiling a .292 batting average, in the high-scoring Players League that used a lively ball rather than the National League’s dead ball. He also played seven field positions in 1890, all except first base and catcher, to demonstrate a wide range of fielding ability.38 This flexibility to be a utility player extended Radford’s career in professional baseball, since it gave clubs another reason to overlook his Sabbatarian beliefs about Sunday baseball, which once again became an issue in 1891.

When the Players League folded after its lone season in 1890, the Boston club of the American Association acquired Radford’s services for the 1891 season.39 This club was the former Boston club in the Players League, which was allowed to transfer to the American Association despite the objection of the Boston club in the National League. Part of the deal was that the American Association team could not publicize itself as being from Boston, so the club adopted the nickname Reds to promote its games at the Congress Street Grounds.

Radford no doubt was happy to play baseball once again in his hometown, but his return also revived the Sunday baseball issue that had plagued his two previous years in the Sunday-playing American Association. His Sabbatarian beliefs were a rarity among ballplayers in the American Association, as the league’s only other recognized Sabbatarian in 1891 was Scott Stratton, a pitcher for the Louisville club.40 While the Boston Reds played road games in Western cities on Sunday, the club also played several Sunday exhibition games at the Rocky Point Grounds in Rhode Island, a Sunday baseball haven that operated with legal impunity in contravention of state law.41 Despite having to substitute for Radford in these Sunday games, the Boston Reds easily won the American Association championship in 1891.

Minnie Radford gave birth to the couple’s only child, Ruth Hale Radford, on November 20, 1891.42 The Radford family relocated from Cambridge to Hyde Park to be closer to Paul’s ill father.43

When the American Association merged with the National League after the 1891 season, Radford had to troll for work yet again when Boston was not among the four American Association clubs absorbed into the National League. With Sunday games permitted in the National League beginning in 1892, his employment search was even more challenging. The Washington club, which transferred from the Association to the National League as part of the merger, acquired his services for the 1892 season.44

Radford lasted three seasons with Washington, the longest stretch of his baseball career with the same club. He experienced minimal issues with Sunday baseball, as Washington played just eight to ten Sunday road games each season. Paul remained one of a tiny fraction of ballplayers during the 1890s who exercised their Sabbatarian beliefs to abstain from playing on Sunday. By 1894 Radford was one of “three prominent players rigidly opposed to Sunday playing,” the other two being pitchers Addison Gumbert and Bill Hutchison.45 Cleveland pitcher Cy Young also practiced strong Sabbatarian beliefs in 1894, although he recanted that position in 1895 and thereafter did pitch on Sundays.46

As a utility player for the untalented Washington club, Radford remained in the major leagues by utilizing his fielding skills to play multiple outfield and infield positions and by exercising patience at bat to get on base, posting top-10 levels of walks in 1892 (86) and 1893 (104). Neither effort lifted Washington higher than 10th place in the 12-team National League standings those three years.

Radford’s father, “one of Hyde Park’s foremost citizens,” died in November 1894.47 After the funeral, Radford retired from major-league baseball at age 33. The Philadelphia Inquirer noted that he had inherited enough money and property “to make himself altogether independent of base ball in the future.”48 For the next dozen years, Radford played baseball for the love of the game, rather than the money.

During his 12-year major-league career, as he pursued his Sabbatarian beliefs to abstain from Sunday baseball, Radford compiled unexceptional lifetime statistics: .242 batting average, .901 fielding average, and 0-4 won-loss pitching record. However, his .351 on-base percentage, which ranks him among the top 700 players lifetime, does point to his skill at becoming a baserunner despite his relatively weak hitting.

Like many players of his era, Radford played minor-league baseball after his major-league career. In 1895 he joined the Scranton, Pennsylvania, club in the Eastern League, but he was released in July when the club “insisted that he play on Sunday” in the many upstate New York cities that were then experimenting with Sunday baseball.49 For 1896 he played with the Bangor, Maine, club in the New England League, which did not play Sunday baseball. Radford played 103 games at shortstop to help Bangor to a disputed first-place finish.50 He crossed paths in 1896 with another staunch Sabbatarian, future major-leaguer Walter Woods, who played for the Portland club. When Bangor dropped out of the New England League after the league awarded the 1896 championship to Fall River, Radford joined the Hartford, Connecticut, club in the Atlantic Association (where only two New Jersey clubs staged Sunday games) to play shortstop for the 1897 season.

Now financially comfortable, Radford worked part time as a machinist.51 In 1901 he moved his family into a house at 62 Highland Street in Hyde Park, where he lived for the next four decades.52 He continued to play baseball on Saturday afternoons and holidays for semipro teams in eastern Massachusetts, including the town teams in North Attleboro and Norwood.53 Because Massachusetts law continued to forbid Sunday ballgames (both amateur and professional), this environment meshed well with his Sabbatarian beliefs. During 1903 Radford played second base for the Hyde Park town team, returning to his roots in baseball two decades earlier.54 In 1904 he joined the Lynn Association semipro team that played a more ambitious schedule, with games during the week as well as on Saturdays and holidays.55

On August 16, 1904, Radford suited up one last time to play in a major-league ballgame, with the Chicago club of the National League for a doubleheader against Boston at the South End Grounds.56 Because shortstop Joe Tinker was injured, manager Frank Selee sought a capable short-term replacement rather than continue to use utility player Shad Barry. However, after Barry played shortstop in the first game of the doubleheader, the second game was rained out, so the 43-year-old Radford never made an official appearance for Chicago. Radford played with the Lynn Association team for the remainder of 1904 as well as the 1905 season.57

For the 1906 season, Radford returned to the minor leagues to play right field for the Lynn club in the New England League.58 However, the 44-year-old Radford produced a very subpar .151 batting average in 26 games for Lynn.59 Radford was released in early June.60 He played one more year of semipro ball, with the Hyde Park town team in 1907, before retiring from the baseball diamond.61

Radford lived a quiet life with his family in suburban Hyde Park, where he continued his work as a machinist.62 When the town of Hyde Park was absorbed into the city of Boston in 1912, the Boston Post noted that “Paul Radford was Hyde Park’s one contribution to major league baseball.”63 In September 1922 Radford appeared in one more baseball game, when the 60-year-old played a few innings at shortstop for the National League old-timers in a charity game in Boston to benefit Children’s Hospital.64

In January 1930 the Newspaper Enterprise Association produced a syndicated article about Radford and his lucky horseshoe, since the Boston Red Sox were interested in its whereabouts.65 The horseshoe hadn’t been seen since 1894 when the South End Grounds burned down.

Paul Radford died on February 21, 1945, at his home in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Boston and is buried in the Brookdale Cemetery in nearby Dedham.66

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and verified for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Sources

Baseball information and statistics, unless otherwise footnoted, are from the Paul Radford pages, both major and minor league, at the Baseball-Reference.com website.

Notes

1 “Paul R. Radford,” New York Clipper, December 22, 1894.

2 Charlie Bevis, Sunday Baseball: The Major Leagues’ Struggle to Play Baseball on the Lord’s Day, 1876-1934 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 145-147.

3 Birth records for Roxbury in 1861 in the Massachusetts State Archives (Volume 142, Page 314).

4 Federal census records for 1870 and 1880 for Benjamin Radford, Hyde Park, Norfolk County, Massachusetts.

5 “Benjamin F. Radford,” Hyde Park Historical Record, January 1892.

6 Town Register and Business Directory of Hyde Park, 1879.

7 Paul was listed as a student in the 1880 federal census (when age 18) and in the Town Register and Business Directory of Hyde Park, 1882 (when age 20).

8 “Paul R. Radford,” Boston Globe, October 1, 1883.

9 After the 1878 season the remnants of the New England Association and the International Association congealed into one league for the 1879 season, called the National Association (dropping the “inter” since there was no longer a Canadian team). This organization reduced to a three-team league for 1880 (with no teams in New England) and then disbanded before the 1881 season.

10 His father was listed as a trustee of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Hyde Park in the Town Register and Business Directory of Hyde Park, 1879; his father’s biography in the Hyde Park Historical Record, January 1892, also notes that he was a Methodist.

11 Alexis McCrossen, Holy Day, Holiday: The American Sunday (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 49-50.

12 Abram Herbert Lewis, A Critical History of Sunday Legislation from 321 to 1888 A.D. (New York: Appleton, 1888), 226.

13 Box scores in Boston Globe, October 22 and 29, 1882.

14 “Baseball,” New York Clipper, December 2, 1882.

15 “Fair Balls,” Detroit Free Press, June 10, 1883, quoted in Edward Achorn, Fifty-Nine in ’84: Old Hoss Radbourn, Barehanded Baseball and the Greatest Season a Pitcher Ever Had (New York: Smithsonian Books, 2010), 118-119.

16 “Contracts Approved,” Cleveland Herald, November 27, 1883.

17 “The Providence Club,” New York Clipper, January 12, 1884.

18 “Paul R. Radford,” Boston Globe, October 18, 1884.

19 “The Jonah Found,” Boston Globe, May 27, 1888.

20 “From the Hub,” New York Clipper, December 5, 1885.

21 Arthur Aldridge, ed., Brawn and Brain: Considered by Noted Athletes and Thinkers (New York: John B. Alden Publisher, 1889), 24.

22 Aldridge, Brawn and Brain, 25.

23 Marriage records for Cambridge in 1885 in the Massachusetts State Archives (Volume 362, Page 299).

24 “Cambridgeport,” Cambridge Chronicle, October 24, 1885.

25 Cambridge City Directory, 1885-1890.

26 “From the Hub,” New York Clipper, March 13, 1886.

27 “Athletic Mention,” Rocky Mountain News, October 18, 1886.

28 “When They Will Play,” New York Times, March 10, 1887.

29 “Baseball Gossip,” National Police Gazette, October 6, 1888.

30 “Notes of the Game,” New York Times, August 23, 1887.

31 “Base-Ball and Athletics,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 6, 1887.

32 “Paul Revere Radford,” New York Times, February 24, 1945.

33 “The Metropolitans Sold,” New York Times, October 9, 1887.

34 Bevis, Sunday Baseball, 68.

35 “Sure of Second,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 27, 1888.

36 “Base Ball Matters,” Brooklyn Eagle, November 9, 1888.

37 “Smith and Radford Sign,” Boston Globe, December 21, 1888.

38 Fielding register on Radford’s page at Baseball-Reference.com website.

39 “Boston May Have Trouble Over Radford and Stricker,” Boston Globe, February 14, 1891.

40 “Base Ball,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 3, 1891.

41 Charlie Bevis, “Rocky Point: A Lone Outpost of Sunday Baseball in Sabbatarian New England,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History & Culture, Fall 2005: 84.

42 Birth records for Hyde Park in 1891 in the Massachusetts State Archives (Volume 413, Page 469).

43 Town Register and Business Directory of Hyde Park, 1891.

44 “Barnie Gets Radford,” Boston Globe, January 30, 1892.

45 “Personal,” Sporting Life, February 16, 1895.

46 Bevis, Sunday Baseball, 117.

47 “B.F. Radford,” Boston Daily Advertiser, November 28, 1894.

48 “Chat of the Diamond,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 16, 1894.

49 “Diamond Dust,” Scranton Tribune, July 26, 1895.

50 Charlie Bevis, The New England League: A Baseball History, 1885-1949 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008), 97-99.

51 Town Register and Business Directory of Hyde Park, 1898-1900.

52 Town Register and Business Directory of Hyde Park, 1901-1913; Boston City Directory, 1912-1945.

53 Box scores in Boston Globe, May 22, 1898, August 26, 1900, and July 14, 1901.

54 “Hyde Park to Open Memorial Day – Paul Radford Plays Second,” Boston Globe, May 19, 1903.

55 “Lynn Association Baseball Team Has Made Great Record,” Boston Globe, August 6, 1904.

56 “With Selee’s Band: Old Paul Radford to Get Into the Game Against Boston This Afternoon,” Boston Globe, August 16, 1904.

57 Box scores in Boston Globe, August 19, 1904, and May 21, 1905.

58 “Radford to Play in Lynn,” Boston Globe, April 1, 1906.

59 Minor-league page for Paul Revere Radford, which stands alone from Radford’s standard pages at the Baseball-Reference.com website.

60 “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, June 5, 1906.

61 “South Framingham 7, Hyde Park 3,” Boston Globe, June 23, 1907.

62 Federal census record for 1910 for Paul Radford, 62 Highland Street, Hyde Park, Norfolk County, Massachusetts; federal census record for 1920 for Paul Radford, 62 Highland Street, Boston, Suffolk County, Massachusetts.

63 “Who’s Who in Hyde Park, Soon to Be Boston’s Newest Ward,” Boston Post, November 12, 1911.

64 “Old Timers Again on Diamond Before 20,000,” Boston Globe, September 12, 1922.

65 William Braucher, “Hooks and Slides,” Lowell Sun, January 13, 1930.

66 “Paul Radford, Old-Time Ball Player, Is Dead,” Boston Globe, February 23, 1945; FindaGrave.com website.

Full Name

Paul Revere Radford

Born

October 14, 1861 at Roxbury, MA (USA)

Died

February 21, 1945 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.