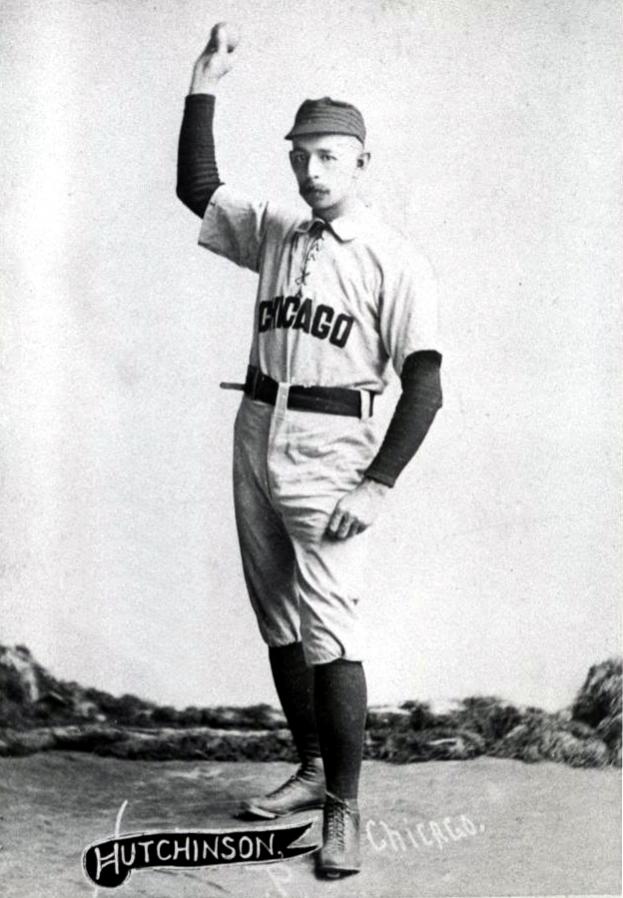

Bill Hutchison

Bill Hutchison was among the last of a breed. Over a three-year stretch, from 1890 to 1892, the ironman right-hander averaged 40 wins, 595 innings, 63 complete games, and 65 starts per season. He led the NL in every one of those statistical categories each season during a time when the pitching distance to home plate was 55½ feet. In 1893, the distance from the mound to home plate was increased to 60 feet 6 inches to generate more offense; that change also ended Hutchison’s statistical dominance. Here’s the story of a reluctant and oft overlooked hurler, who began his professional baseball career late, but whose impact helped bring about substantial rule changes for pitching.

Bill Hutchison was among the last of a breed. Over a three-year stretch, from 1890 to 1892, the ironman right-hander averaged 40 wins, 595 innings, 63 complete games, and 65 starts per season. He led the NL in every one of those statistical categories each season during a time when the pitching distance to home plate was 55½ feet. In 1893, the distance from the mound to home plate was increased to 60 feet 6 inches to generate more offense; that change also ended Hutchison’s statistical dominance. Here’s the story of a reluctant and oft overlooked hurler, who began his professional baseball career late, but whose impact helped bring about substantial rule changes for pitching.

William Forrest Hutchison was born on December 17, 1859, in New Haven, Connecticut.1 He was named after his parents, Reverend William Hutchison and Forresta Germana (Shepherd) Hutchison. The elder Hutchison, who earned his bachelor’s degree from Yale University and subsequently a doctorate of divinity there as well, was a respected Congregational minister and missionary, and served as the principal of Norwich (Connecticut) Free Academy, an independent college-preparatory school, from 1865 to 1895.2 The Hutchisons also had a daughter, Sylvia, who died before reaching adulthood.

As the son of an established New England family, young Bill benefited from an excellent education. He attended Heness German School in New Haven for his first eight years, and then Norwich Free Academy, graduating in 1875. He followed in his father’s footsteps, enrolling at Yale, where he was by all accounts an exemplary student. He was a member of the Glee Club, College Choir, Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, and the Scroll and Key Club, the institution’s oldest secret society. Bill also played baseball for Yale, excelling on the field as a shortstop and occasionally as pitcher, and served as team captain in 1880, his senior year. According to his obituary published by Yale, Bill took engineering courses at Sheffield Scientific School at Yale in the 1880-1881 academic year, and remained on the baseball team for a third season, helping it to the American College Association championship.3

Baseball served as an amateur leisure pursuit for Hutchison as he embarked on a career as a businessman. After a short stint in Biddeford, Maine, learning about cotton manufacturing, he relocated to Kansas City and entered the railroad business. He took a job as an agent with the Burlington, Cedar Rapids & Northern Railroad Company, eventually relocating to Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Standing 5-feet-9 and weighing 175 pounds, Hutchison developed a reputation as a hard thrower for town teams in Cedar Rapids. His professional baseball career can be traced to 1883, when he appeared in a few games for Springfield (Illinois) in the Northwestern League. The following season he hurled two games for the Kansas City Cowboys in the only season of the Union Association, considered a major league. Newspapers described him as a “phenomenal pitcher”4 and of “local distinction”5 in May 1887. According to one report, Albert Spalding, president of the Chicago Base Ball Club in the National League, had traveled to Cedar Rapids in an attempt to sign him.6 Other papers reported erroneously that the hurler had signed with Chicago.7 He eventually signed with Des Moines in the Northwestern League, reportedly for an exorbitant salary of $3,500, and joined the club around June 1. In just over half a season of the circuit’s final year of existence, the 27-year-old Hutchison went 27-10 and completed 37 of his 39 starts as the Hawkeyes finished fourth (73-47) in an eight-team league.

Hutchison spurned professional offers from National League clubs in Chicago, Detroit, and New York in 1888, supposedly because he thought that “the reserve rule smacks too much of slavery.”8 A successful businessman by this point, Hutchison didn’t need baseball to earn a living; nonetheless, the attraction of the sport proved too much for him to ignore. In early July of 1888 he signed with Des Moines, a charter member of the 10-team Western Association.9 In uniform again for just of half the season, Hutchison went 23-10 and completed 32 of 34 starts, helping the Prohibitionists to second place (73-40). They finished a half-game behind the champion Kansas City Blues, led by a quartet of hurlers, one of whom was 18-year-old future Hall of Famer Kid Nichols.

Despite his objections to the reserve clause, Hutchison signed with Chicago in mid-October. Led by 37-year-old player-manager Cap Anson, it was coming off a second-place finish and was expected to compete for the pennant in 1889. However, the team played inconsistently, struggling to play .500 ball (67-65) and finishing 19 games behind the champion New York Giants. A bright spot was the emergence of Hutchison as the team’s most effective hurler. He led the staff in almost every category, including complete games (33) and starts (36), innings (318), and wins (16), tying Frank Dwyer and Ad Gumbert, However, strikeouts (136) were the only mark that placed him within the top 10 of the league’s pitchers.

At the time pitchers tossed from a box measuring 5½ feet long (from home to second base) and 4 feet wide. In his excellent history of nineteenth-century baseball fields, Erik Miklich explained that the rear of the box was located 55½ feet from the center of home plate.10 Pitchers were required to have one foot on the back line when delivering the ball and to hold the ball so that the umpire could see it. They threw from a flat surface; the pitcher’s mound was not introduced until the twentieth century.

Hutchison distinguished himself off the diamond as much as he did on it. Whereas the sport was characterized by rough-and-tumble, hard-living players, Hutchison was noted for his education, behavior, and upper-class background. “He is as diffident as a modest girl, is a gentleman and don’t [sic] drink and bum,” reported one newspaper about the devout Congregationalist.11 Another gushed that Hutchison “was never known to smoke, chew, drink, or swear, but … can outpitch anything that walks.”12 He was even described as the “premiere (sic) danseuse of Chicago pitchers” – apparently meant as a compliment.13 Given his religious convictions, he refused to play on Sundays.14 Sportswriters gave Hutchison several sobriquets; Willie William, Willie Bill, and Hutch were the most common. He was described as “wild” as a rookie in 1889; however, the moniker Wild Bill appeared later in his career and after the pitching distances were changed in 1893.15 Contemporaneous newspapers, even those in Chicago, often misspelled his name, inserting an extra “n” – a tendency that the Chicago Inter Ocean even noted.16

During spring training in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1890, team President Spalding told reporters, “I think [Hutchison] will become the star of the league, and I am not forgetting Clarkson either.”17 Sportswriters must have had a field day with the sporting-goods magnate’s audacity to compare Hutchison with the sport’s premier hurler, John Clarkson, who had led the NL in wins (49) for the third time in five seasons and innings (620) for the fourth time in that stretch. But Spalding’s pronouncement was prescient: Hutchison commenced a phenomenal three-year stretch.

Hutchison began his second season by defeating the Reds, 5-4, in front of 6,500 spectators in League Park in Cincinnati.18 The Colts, as the Chicago team was called, struggled to play .500 ball for almost four months. In the first game of a double header against the Cleveland Spiders in League Park on August 6, Hutchison lost 8-1 to hurler making his first big-league appearance, Cy Young. The following day, the club languished in fifth place (44-43), 14½ games behind the front-running Brooklyn Bridegrooms. Unexpectedly, the club went on a roll the next day. Hutchison tossed a one-hitter, yielding only a scratch hit in the ninth inning, in beating the Cleveland Spiders, 7-0, on August 8.19 The Colts won 18 of 23 games, all but four on the road, and returned to Chicago on September 4 to play their final 27 contests in front of partisan fans at West Side Park. The homestand commenced with 11 straight victories, two of which were shutouts by Hutchison. The Chicago Inter Ocean gushed that the right-hander’s fastball “came like meteors through the star-lit sky” in his five-hit, 1-0 victory against the Reds on September 6.20 The Colts eventually moved into second place and pulled to within five games of the Bridegrooms with seven left to play, but the deficit proved too much to overcome. On September 29 Hutchison tossed what might be his best game as a big leaguer, a one-hit shutout with 10 K’s against the Boston Beaneaters. He also had the winning hit, a two-run single in the seventh.21

Hutchison led the NL in wins (41), innings (603), starts (66), complete games (65), and games (71); and finished second in strikeouts (289) and walks (199) to the Giants’ 19-year-old phenom, Amos Rusie. Pitching was a young man’s position, making the accomplishments of the 30-year-old Hutchison even more striking. He was the oldest, by two years, of the 13 20-game winners and 12 hurlers who logged at least 300 innings.

After the regular season Hutchison participated with the Colts in a series of exhibition games against the Milwaukee Brewers of the Western Association and the Whitings, the Chicago City League champions, and continued this practice in subsequent seasons, though against different teams, on “barnstorming” tours to earn extra income. Throughout his baseball career, he spent his offseasons in Cedar Rapids, where he continued to work as a railroad executive.

Hutchison was known for his primary pitch, the fastball, though he later developed a curveball. Sportswriters described his heater in poetic terms and by how hard he threw at a time (1889-1892) when games averaged fewer than seven strikeouts. “[T]he muscles jut out from his forearm like the roots of an old oak tree,” exclaimed the Inter Ocean about Hutchison’s physical prowess, “and sometimes he casts a ball athwart the batter that it looks like a streak of pale moonshine in a cellar.”22 Hutchison finished runner-up to Rusie, considered to have the most overpowering heater in the game, in punchouts in 1890 and 1891. He then topped the Hoosier Thunderbolt by nine strikeouts in 1892, fanning a career-best 314. Overhand, hard-throwing pitchers were still a relative novelty in baseball – the sport was still evolving, pitching specifically. As John Thorn, the official historian of baseball, explained, the NL required pitchers to throw underhanded through the 1883 season, lifting all restrictions in 1884; in addition, batters were permitted to request high or low pitches until 1887.23 An excerpt from the Inter Ocean captures the exciting, albeit exaggerated, effect Hutchison’s fastball had on spectators and fans: “[Hutchison] brought so much speed down to the grounds with him that part of the ball was still kissing his lily fingers when the other part was eating into the catcher’s mitt. He really mined the ball in so swiftly that when the air came together again, it was with a noise like hitting a fat man with a bass viol.”24

After four weeks of spring training primarily in Denver playing against clubs in the Western Association in 1891,25 the Colts, and Hutchison, continued their momentum from the previous campaign. The Opening Day start against the Pirates in Pittsburgh on April 22 went to Pat Luby, coming off a fabulous rookie campaign with 18 consecutive victories.26 Hutchison relieved Luby to begin the eighth, scored the tying run in the ninth, and the Colts won the game in the 10th.27 Hutchison “was entirely too much” for the Pirates the next day, tossing a six-hitter to win his first start, 9-2.28

The Colts’ 1891 season was filled with tension and controversy. It proved to be the last time the team would seriously contend in a pennant race until 1906, when it won a franchise-record 116 games. In and out of the top spot during the first three months, the Colts regained sole possession of first place on July 22. Once again, Hutchison carried the team and was “always the man expected to help out,” noted the Chicago Tribune about the hurler’s ironman strength.29 The pennant race boiled down to three teams: the Colts, the Beaneaters, and the Giants. On August 6 in Boston Hutchison battled the Beaneaters’ Kid Nichols for 13 innings. Nichols was en route to winning 30 games for the first of seven times in eight seasons, but Hutchison emerged victorious, 3-2.30

The Colts’ title aspirations suffered a serious blow on August 13 when Hutchison suffered what the Tribune called a strained tendon in his left leg.31 Given some extra time between starts, Hutchison forged on and the Colts won 11 straight games beginning August 15. On August 31 the two strikeout kings – Hutchison and the Giants’ Rusie – engaged in an 11-inning scoreless tie. Sportswriter Leonard Washburn of the Inter Ocean gushed, “[T]here’s been nothing like it in the league for years.” It set up a tumultuous last month of the season.32 Hutchison’s two-hit, 10-1 victory against John Clarkson and the Beaneaters on September 3 extended the Colts’ lead to six games over Boston, and the Colts moved to a season-best seven games the next day. When Hutchison tossed another gem against the Beaneaters 11 days later – a four-hit, 7-1 win at South End Grounds – the Tribune announced euphorically, “Anson and his Colts have captured the pennant beyond question.”33

The Colts beat the Beaneaters again the next day to increase their lead to 6½ games, but then the roof caved in. The Beaneaters won the rubber match of the series, the first of 18 straight victories (plus a tie), while the Colts lost four straight games, including all three to the Giants in New York. The Colts and Hutchison suffered a crushing loss on September 28 to the second-division Cleveland Spiders and their hurler, described as a “big slack twisted lob … who throws a ball like a man climbing a stake and rider fence.”34 That “lob” was Cy Young.

Nonetheless, the Colts maintained a precarious half-game lead. Controversy and charges of cheating exploded the next two days, when the Beaneaters overwhelmingly beat the Giants in consecutive doubleheaders. The Inter Ocean ran the headline “Looks Like a Conspiracy,” and the Colts were suddenly 1½ games behind the Beaneaters with three games to play. Hutchison took the mound against the cellar-dwelling Reds on October 1 in the most important game of the season. Despite playing in front of a partisan crowd in the Windy City, the Colts lost, 5-1, subdued by Tony Mullane’s two-hitter, thus ending their pennant quest.35 The Beaneaters won the pennant, but as historian Brendan Macgranachan explained, the club had to wait until November 11 to be officially crowned champion.36 Colts President James A. Hart filed a formal complaint with the NL office, which investigated the Beaneaters’ sweep of consecutive twin bills against the Giants, an injury-riddled club that played without many of its top players.37

Hutchison once again proved to baseball’s rubber-armed twirler. He led the NL in 44 wins (11 more than runners-up Clarkson and Rusie), games (66), starts (58), complete games (56), and innings (561).

The NL experienced massive change in 1892. The league expanded from eight to 12 teams, absorbing four clubs from the American Association, which disbanded after 10 seasons; the schedule increased from 140 to 154 games; and the season was divided into two halves, setting up a postseason championship series.38 Once again expected to challenge for the NL title, the Colts got off to a disastrous start, losing nine straight games in April. The Chicago Tribune blamed the Colts’ four-week training at Hot Springs, Arkansas, where the mineral baths supposedly zapped the players’ energy.39 Languishing in 10th place, the Colts unexpectedly won 13 straight games beginning on May 4, highlighted by Hutchison’s two-hitter against the Giants at South Side Grounds in Chicago on May 7, as well as a three-hitter against the Pirates and 35-year-old future Hall of Famer Pud Galvin on May 21.40

That success, however, masked the fact that the Colts were an offensively challenged team, scoring a league-low 4.3 runs per game and batting just .235. They finished in eighth place in the first half (31-39) and then seventh (39-37).41 Without Hutchison, the Colts would have fared far worse. He won three of his last four decisions, including a five-hit shutout in the season finale against the St. Louis Browns in a game that had been relocated to Kansas City, to finish at 36-36.42 The 32-year-old once again led the league in wins, innings (622), complete games (67), and starts (70). He also paced the circuit in strikeouts (314) and strikeout/walk ratio (1.65).

In order to generate more revenue and fan interest after a financially troublesome season, major-league baseball implemented far-reaching changes to pitching aiming to increase offensive production. As John Thorn and Eric Miklich explained, a 12-by-4-inch pitcher’s plate replaced the pitcher’s box and the pitching distance was increased to the now-familiar 60 feet 6 inches.43 The modifications had a dramatic effect on the game. Scoring increased from 10.2 to 13.2 runs per game; batting average rocketed from .245 to .280; the number of .300 hitters ballooned from 8 to 30. As for pitchers, total strikeouts decreased dramatically (from 5,978 to 3,342), though walks actually fell by 0.5 percent.44 The new pitching distance, with its increased physical stress on the pitchers themselves, signaled the end of the Hutchison-like ironman. No pitcher in big-league history since Hutchison has hurled 500 innings, let alone 600; while the 400-inning starter became rarer (dropping from 11 in 1892 to four in 1893).

The new rule changes marked the end of Hutchison’s three-year stretch of leading the league in wins, innings, starts, complete games, and games pitched. The oldest regular starting pitcher in the league, he hurled three more full seasons (1893-1895), yet did not lead the NL in any statistical category. He was among the pitchers most affected by the increased pitching distance; his strikeouts per nine innings dropped from 4.4 to 2.2, while his walks per nine increased from 2.9 to 4.2.

As the Colts concluded spring training in Atlanta and prepared for the 1893 season, which was reduced to 132 games, the Tribune opined that the club “seems stronger on paper than it did last year,” and suggested that “the team must be carried by its pitchers.”45 That pronouncement seemed accurate when Hutchison looked “invincible,” throwing a four-hitter in an 11-1 victory against the Reds in his season debut on April 28.46 By the end of May, however, it was clear that pitching was one of the club’s weaknesses. The 33-year-old Hutchison struggled mightily in adjusting to the new pitching distances. The Tribune regularly lambasted his “poor pitching.”47 The Beaneaters pummeled him for 20 hits (10 earned runs) in an 18-2 shellacking on May 29 in Boston.48 Three days later, the Athletics showed him no brotherly love in Philadelphia by victimizing him for 23 hits (seven earned runs) in a 16-1 laugher. That led the Tribune to run the subheading “Hutch Pitched Like a Farmer.”49

Hutchison gradually found his groove. On occasion he flashed his past mastery, such as on July 3, when he was once again the “terrific old Hutch.” He tossed a three-hit shutout against the reigning champion Beaneaters and Kid Nichols, 3-0, walking one, yet registering no strikeouts.50 However, those dominating moments were fleeting. Despite his age, Hutchison still proved to be the ninth-place (56-71) Colts’ most durable hurler, pacing the staff in starts (40), complete games (38), appearances (44), and innings (348⅓), all of which ranked within the top 10 in the league. He won 16 games and lost 24, tied for second most in the NL.

Baseball’s offensive explosion continued in 1894, with the NL’s cumulative batting average jumping to .309 – 64 points higher than two years earlier – while home runs went from 417 to 629, scoring mushroomed to 14.8 runs from 10.2 per game, and ERA ballooned from 3.28 to 5.33 during that two-year span. Hutchison characterized those trends on Opening Day in the Queen City. He surrendered 12 hits and walked five in a 10-6 loss, but also blasted a home run that “bounded over the fence” at League Park.51 A .205 hitter up to this point in his career, the 34-year-old Hutch batted a personal-best .309 and clubbed six of his 12 lifetime home runs that season.

The aging right-hander again occasionally conjured up his past. “Hutchison pitched a game that recalled some in which he twirled when Chicago was a factor in the league race,” waxed the Tribune nostalgically about his 3-1 victory over the Browns on May 24. The story added that “His speed and curves were things of joy.”52 But more often than not, Hutchison and the eighth-place Colts (57-75) were on the other side of those contests.” Following Hutchison’s “wild and unsteady” outing against the Giants on June 29, yielding 16 hits and walking seven in a 14-8 loss, the Tribune opined dejectedly, “Once invincible and the dread of all opponents, [Hutchison] was the easiest kind of target.”53 In his first year with the club, 24-year-old Clark Griffith emerged as the Colts’ most effective hurler, winning 20 games for the first of six straight seasons and seven times in his Hall of Fame career. However, Hutchison (14-16) posted a 6.03 ERA, more than double the 2.76 average during his three-year dominant stretch. “Hutchison’s nerve seems to have forsaken him after years of success and victory,” ranted the Tribune.54 Nonetheless, he still paced the staff with 279 innings, 34 starts, and 28 complete games, tied with Griffith.

After spring training in Galveston, Texas, both the Colts and Hutchison seemed rejuvenated as the 1895 season unfolded. In his debut in St. Louis, on April 20, the 35-year-old hurler “pitched as he did when he was the best twirler in the league,” gushed the Tribune, tossing a three-hitter to beat the Browns, 11-5; his eight walks and the club’s seven errors led to all the Browns’ runs being unearned.55 On May 6, as part of the Colts’ seven-game winning streak to move to within one game of first place, Hutchison’s “curves were too fast” for the Washington Senators, exclaimed the Tribune, as Hutch tossed his first shutout in two seasons, yielding five hits and only one free pass in a 5-0 victory.56

The Colts contended for the flag through the dog days of summer. They were led on offense by 43-year-old player-manager Cap Anson (who batted .335), rookie Bill Everitt (129 runs and .358 batting average), and Bill Lange (120 runs and .389 average). Pitching highlights were the emergence of Griffith (26 wins) as one of the best hurlers in the league, and the resurgence of 30-year-old Adonis Terry (21 wins). The club’s third option as starter, Hutchison went through some horrendous patches as the season progressed, including an abysmal 20-3 loss in Boston on June 13, when he surrendered 18 hits with 10 earned runs. That led the Inter Ocean to opine that he “acted like a man in some kind of hypnotic trance.”57 On August 3 Hutchison scored his biggest triumph since his halcyon days, whitewashing the Browns on a four-hitter to keep the Colts 3½ games off the Spiders’ pace. That lead was reduced to three games the next day before the Colts imploded, losing 15 of 21 games and eventually finishing in fourth place (72-58). It proved to be the last full season in the major leagues for Hutchison (13-21, 291 innings, and 30 complete games).

Transferred to the Minneapolis Millers of the Western League in 1896, Hutchison was far from washed up, leading to rumors that he would be recalled or sold to another major-league team. However, nothing materialized. Hutchison led the circuit with 38 victories, helping the club to the regular season and postseason championship.58

The St. Louis Browns drafted Hutchison from the Millers in the offseason, but the hurler’s return to the majors in 1897 was abbreviated.59 In his debut, his former team pummeled him for 17 hits in a 9-2 laugher.60 Hutchison made only five more forgettable appearances and was then returned to the Millers, where he went 14-24. After spending a year away from the diamond in retirement, the 39-year-old rubber-armed Hutchison rejoined the Millers in 1899, helping them to within one game of the Western League regular-season title. According to the 1900 Reach Guide, Hutchison went 14-9.61

Hutchison retired for good after the 1899 campaign. In parts of nine big-league seasons, he won 182 and lost 163, logged 3,079⅓ innings, and completed 321 of 346 starts.

As successful off the diamond as on it, Hutchison had relocated to Kansas City in the late 1890s, and was an executive and contracting agent in freight traffic for the Kansas City Southern Railroad. A lifelong bachelor, Hutchison was active in the First Congregational Church.

Hutchison died at the age of 66 on March 9, 1926, in Kansas City. The cause of death was cardiac weakness. He was buried at the family lot at Yantic Cemetery in Norwich, Connecticut.

Acknowledgments

The biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and verified for accuracy by the SABR fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, the player’s Hall of Fame file, the online archives for the Chicago Inter Ocean and Chicago Tribune and other newspapers via Newspapers.com, and Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Throughout his baseball playing career, Hutchison’s name was often misspelled as Hutchinson. According to numerous sources, “Hutchison” is the correct spelling: Sources include US Census reports, Yale University yearbooks, and his obituary published by Yale, as well as a player questionnaire from the Baseball Hall of Fame filled out by the player’s relatives.

2 Jeff Brown, “Check Out ‘the Hutch,’” NFA Magazine, Fall 2015: 20.

3 “William Forrest Hutchison, B.A. 1880,” Obituary Record of Yale Graduates 1925-1926. [From the player’s Hall of Fame file.].

4 Gazette (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), May 27, 1887: 1.

5 Morning Democrat (Davenport, Iowa), May 10, 1887: 2.

6 “Slovenly Sport, Inter Ocean (Chicago), May 12, 1887: 2.

7 Gazette (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), May 27, 1887: 1.

8 Omaha Bee, May 31, 1888: 2.

9 Gazette (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), July 5, 1988: 1.

10 Erik Miklich, “The Pitcher’s Area,” 19cbaseball.com. 19cbaseball.com/field-8.html.

11 Omaha Bee, May 31, 1888: 2.

12 “Poor Willie Bill,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 12, 1891: 3.

13 “Outside the Diamond,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), July 8, 1893: 6.

14 “Anson’s Last Day,” Chicago Tribune, January 31, 1898: 4.

15 “Ball-Players to Strike,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), June 20, 1889: 3.

16 Miscellaneous Pastimes, Inter Ocean (Chicago), May 1, 1893: 3.

17 “Anson Lands His Players,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), March 9, 1890: 6.

18 “National League,” Inter Ocean (Chicago) April 20, 1890: 2.

19 ‘Downed By Darby O-Brien,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), August 9, 1890: 6.

20 “Won on a Single Hit,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), September 7, 1890: 2.

21 “Hutchison Wins Honors,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), September 30, 1890: 3.

22 “Couldn’t Touch Hutch,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), July 31, 1891: 2.

23 John Thorn, “Pitching: Evolution and Revolution,” Our Game. Origins, August 6, 2014. ourgame.mlblogs.com/pitching-evolution-and-revolution-efd3a5ebaa83.

24 “Discrowned the King,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), May 15, 1891: 1.

25 “Departure of the Colts,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), March 15, 1891: 6.

26 Steve Hatcher, “Pat Luby” SABR BioProject. sabr.org/bioproj/person/4b5f17d6.

27 “First Blood for Anson,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), April 23, 1891: 1.

28 “Their Eyes on the Ball,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), April 24, 1891: 2.

29 “Looks Like Conspiracy,” Chicago Tribune, September 30, 1891: 6.

30 “Hutchison and Victory,” Chicago Tribune, August 7, 1871: 6.

31 “Anson Losing His Grip,” Chicago Tribune, August 13, 1891: 7.

32 Leonard Washburn, “Game of Goose Eggs,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), September 1, 1891: 2.

33 “Boston Has the Blues,” Chicago Tribune, August 14, 1915: 6.

34 Leonard Washburne, “Boston Creeping Up,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), September 29, 1891: 3.

35 Leonard Washburne, “Uncle’s Hard Luck,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), October 2, 1891: 3.

36 Brendan Macgranachan, “The 1891 Pennant Controversy,” seamheads.com, October 12, 2008. seamheads.com/2008/10/12/was-bostons-1891-nl-pennant-tainted/.

37 According to Macgranachan, Hart also wanted the NL to investigate why Giants owner John Day said before those twin bills that he would like to see Boston win the championship. In addition, the scheduling of consecutive doubleheaders smacked of conspiracy. The second twin bill required approval of the league and at least six other teams. Why would the Giants agree to four games in two days, wondered Hart, if they club was not all full strength.

38 “The 1892 Split Season,” SABR Research Journal. research.sabr.org/journals/1892-split-season.

39 In 1886 Al Spalding, president of the Chicago club, was the first to conduct spring training in Hot Springs, a novel practice that other teams quickly emulated. However, the were many detractors who claimed the mineral baths made the players lethargic. “Colts Will Move On,” Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1892: 10.

40 “Long Live Hutch,” Inter Ocean, (Chicago), May 8, 1892: 3; “Up and Up They Go,” Inter Ocean, May 22, 1892: 6.

41 “The 1892 Split Season,” SABR Research Journal. research.sabr.org/journals/1892-split-season.

42 “Season Well Ended,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), October 16, 1892: 7.

43 Thorne; Miklich.

44 In 1892 there were 6,178 walks; in 1893 they fell to 6,143.

45 “Baseball’s Revival,” Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1893: 12.

46 “Turned the Tables,” Chicago Tribune, April 29, 1893: 7.

47 “Old Hutch Was Easy,” Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1893: 6.

48 “Bean-Eaters Win It,” Chicago Tribune, May 30, 1893: 6.

49 “Anson’s Crew Failed,” Chicago Tribune, June 2, 1893: 6.

50 “Terrific Old Hutch,” Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1893: 7.

51 “Too Wet For Chicago,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), April 21, 1894: 6.

52 “Find One Soft Spot,” Chicago Tribune, May 25, 1894: 8.

53 “Hutchison Bad Eye,” Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1894: 6.

54 “Ball Teams of 1894,” Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1894: 11.

55 “Win With the Bats,” Chicago Tribune, April 21, 1895: 4.

56 “Shut Out by the Colts,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 1895: 8.

57 “Willie Bill Is Easy,” Inter Ocean (Chicago), June 14, 1895: 4.

58 Statistics from Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd edition (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1997).

59 The Millers contested Hutchison’s draft. Ultimately the NL Board of Directors Awarded the player to the Browns. See “World of Sport,” Baltimore Sun, March 1, 1897: 6; and “Millers Are Mad,” St. Paul Globe, March 9, 1897: 8.

60 “The Chicagos Won a Game,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 27, 1897: 11.

61 Record from Reach Base Ball Guide for 1900 (Philadelphia: Reach, 1900), 65. Thanks to SABR members Everett Cope and Cliff Blau for providing this information.

Full Name

William Forrest Hutchison

Born

December 17, 1859 at New Haven, CT (USA)

Died

March 19, 1926 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.