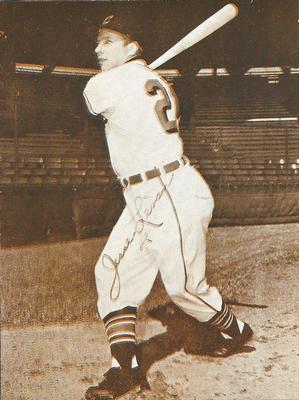

Jesse Levan

Jesse Levan was the last baseball player to be banned for trying to fix games. A two-time minor-league batting champion, he was held back by injuries and was no longer a prospect when he was banished from professional baseball for life in 1959. He always denied conspiring to throw games, but the damning evidence against him came from his own teammates.

Jesse Levan was the last baseball player to be banned for trying to fix games. A two-time minor-league batting champion, he was held back by injuries and was no longer a prospect when he was banished from professional baseball for life in 1959. He always denied conspiring to throw games, but the damning evidence against him came from his own teammates.

Jesse Roy Levan was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, on July 15, 1926. His father, Donald, left the family when Jesse was a baby. He was devoted to his mother, the former Mildred Van Buiskirk. Young Jesse was a baseball star from an early age. As a boy living on Linden Avenue in northeast Reading, he won batting championships in youth leagues with the Hillside Mites and Hillside Midgets. He led the Reading High Knights to the East Penn League title while batting .443 in 13 games. He hit three home runs in one of them. Decades later the Reading Eagle-Times reported that he was “thought by many to be the greatest hitter in Berks County history.”1

It was a rich history. Levan played American Legion ball with the powerful Gregg Post 50 team, whose alumni included Carl Furillo, Vic Wertz, Whitey Kurowski, Curt Simmons, Elmer Valo, and Dom Dallessandro. Naturally, big-league scouts were following the team. In 1943 Cardinals scout Pop Kelchner took Levan to the World Series to see Kurowski, his favorite player. But midway through his senior year he dropped out of school and signed with the Philadelphia Phillies for a $1,000 bonus.

The 17-year-old left-handed-batting center fielder began his professional career with the Wilmington Blue Rocks of the Class B Interstate League in 1944. He immediately stamped himself as a prospect, batting .316 with a .423 slugging percentage. Then World War II intervened. Drafted into the Army in October, Levan served in the 94th Division and won the European Armed Forces batting title with a .343 average. He lost two seasons to military service.

When Levan returned to civilian life in 1947, the Phillies sent him back to Wilmington. At the age of 20 he had filled out to around 200 pounds on a 6-foot frame and displayed newfound power at the plate. He hit 19 home runs, 20 triples, and 19 doubles, ringing up a .512 slugging percentage to go with a .309 batting average. After the Interstate League season ended Levan jumped from Class B to the majors. He made his debut with Philadelphia on the season’s next-to-last day, playing left field against the New York Giants at Shibe Park. In his second time at bat he singled and drove in a run, then scored on a sacrifice fly. He later added a second single and scored again. The next day fellow American Legion Post 50 alumnus Curt Simmons made his debut on the mound, and Levan contributed two more singles to help the 18-year-old Simmons win his first game.

Levan’s 4-for-9 batting line should have impressed the front office, but he had a sore arm. In October the club sent him to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. Reports of his treatment vary; one account says he underwent surgery for bone chips in his elbow, but another version says doctors treated his shoulder and found no structural damage. When Levan reported to spring training in 1948 his throwing arm was still weak. Even worse for his chances, the Phillies had another 21-year-old center fielder, Richie Ashburn, who had batted .362 in Class A the previous season. Levan was sent down to the Phils’ top farm club at Triple-A Toronto. He slammed three homers early in the season, but after 31 games he was demoted to Wilmington. In his third crack at Class B pitching he hit .344 but managed only seven homers. As soon as Wilmington was eliminated from the playoffs, Philadelphia called him up, but he did not play. He would not appear in another big league game for six years.

Despite his gaudy batting average, the Phillies had evidently decided the 22-year-old Levan was not a prospect. His weak arm may have been the reason, but it’s also true that the perennially losing team was assembling a wealth of young players, courtesy of their free-spending new owners, the Carpenter family. Ashburn joined Del Ennis in the outfield in 1948, Granny Hamner took over at second base, and Simmons and Robin Roberts moved into the starting rotation. They were the foundation of the Whiz Kids who won the 1950 pennant.

Philadelphia sold Levan outright to Triple-A Milwaukee. He lasted only a few weeks before he was sent down to Class A Hartford, but soon descended further. He spent time in 1949 at Class B Sunbury and even sank to the bottom of the minors, Class D Bluefield. Milwaukee recalled him in September, but he batted only .256 in the four leagues. The St. Louis Browns gave him a brief look during spring training in 1950. Then the 23-year-old embarked on a discouraging five-year bus tour of the low minors. He overmatched the pitchers at every stop, but nobody except the small-town fans and sportswriters seemed to notice.

Back in Class B with Hagerstown in 1950, Levan won the Interstate League batting title with a .334 average, delivering 13 homers and a .508 slugging percentage, and made the all-star outfield along with Trenton’s Willie Mays. (It was a post-season all-star team; the two did not play together.) That was not enough to move him up; Hagerstown sold him to another Class B club, Raleigh, but he didn’t stay there long in 1951. When Raleigh released him, he hooked on with St. Hyacinthe in Canada’s Provincial League. The independent Class C circuit was a last-chance league for unwanted players, including African Americans. Levan again hammered low-level pitching, batting .347, slugging .557 and belting 17 homers and 36 doubles. The performance at least got him back to the United States in 1952, but he joined another independent league, the Class B Florida International, with Miami Beach. He added a second batting title to his collection, hitting .334 with 10 homers and 35 doubles. A sportswriter called Levan the league’s “most feared hitter.”2 The Double-A Atlanta Crackers tried him out in 1953, but released him after he went 3-for-14, and he returned to Florida. Under manager Pepper Martin at Fort Lauderdale, Levan hit .323, slugged .502 and connected for 16 homers. The next year, when the franchise transferred back to Miami Beach, Levan was batting .348 with 23 homers in August when the Washington Senators bought him for their Class A Charlotte farm club. Somebody had finally noticed him.

Finishing the season with 29 games for the Hornets, Levan lit up the Sally League with a .412 average, .746 slugging, and seven home runs in 114 at-bats. Scout Ellis Clary, the cracker-barrel wit, said, “I wrote to [Washington’s] Calvin Griffith that Levan could do him some good if hitting was still going to be a part of baseball.”3 Levan finished the season on the Senators’ bench, and later said manager Bucky Harris told him he would be with the team the next year. After six years of scuffling, at the prime baseball age of 28, he was back in the majors. Now the bad news: Washington fired Bucky Harris after the season.

In the spring of 1955 the Senators’ ancient owner, Clark Griffith, compared Levan to the best hitter in the franchise’s history, Goose Goslin. “His kind don’t come along very often,” the Old Fox purred. But Washington Post writer Shirley Povich described the prospect as “not much outfielder and not much first baseman.” Povich touted him as Washington’s answer to the Giants’ World Series pinch-hitting hero, Dusty Rhodes. New manager Chuck Dressen quipped that Levan’s best position was “at bat.”4 That’s where Dressen used him on opening day. After President Eisenhower threw out the first ball, the Baltimore Orioles took a 3-2 lead into the sixth inning. With one out and two on, Levan hit for catcher Bruce Edwards. His single chased home the tying run and the Senators went on to win, 12-5. It was a triumphant return, but a short-lived one. Levan delivered only two hits in 15 at-bats over the next month and went from Dusty Rhodes to “hit the road.”

Sent back to Charlotte, he batted .280 in 87 games, his first time below .300 since 1949. He moved up to the Double-A Chattanooga Lookouts in 1956 and stayed there for four seasons, long enough to become the franchise’s all-time home run leader with 83. Setting a lifetime record for minor-league homers is not a popular career choice, but Double-A food and buses beat those in the B and C leagues where he had languished for so long. Now, moving into his 30s, Levan had to be resigned to the role—and paycheck—of a minor-league lifer.

He thrived in the Southern Association, clouting 25, 25, and 26 home runs over the next three seasons. In 1957 he went 18-for-25 during one six-game stretch, including eight home runs, two doubles, and a triple. The Chattanooga News-Free Press called it “the greatest batting spree in minor league history.”

Levan was hitting .337 in July 1959, shortly before his 33rd birthday. His Lookouts teammates were puzzled when manager Red Marion told them to bring sport coats and ties on their trip to Nashville.5 When they arrived at the Andrew Jackson Hotel on July 3, each player was called individually into a room to face Southern Association President Charlie Hurth and Phil Piton, assistant to the president of the National Association, the minors’ governing body. The topic on the table: Jesse Levan.

The newest member of the team, veteran infielder Sammy Meeks, had come over from the Mobile Bears. Shifting his loyalty to his new club, he told manager Marion and owner Joe Engel about a conversation with Levan earlier that season in a Mobile hotel bar. Meeks said Levan introduced him to a gambler who offered to pay him if he would participate in a scheme of sign-giving rather than sign-stealing: While coaching at first base, Meeks was to watch the Lookouts’ shortstop, Waldo Gonzalez. If Gonzalez stood upright, it signaled a fastball; if he crouched, it meant a curve was coming.

Meeks said he refused to take money, but was willing to relay the signs to Mobile batters because he thought it would give his team an edge. Mobile shortstop Andy Frazier joined the conversation and agreed to take the signs from Meeks.6 In the first game of a June 6 doubleheader, Frazier said, Meeks tipped him on two pitches—and both tipoffs were wrong. Mobile won the game 7-3 when first baseman Gordy Coleman hit a grand-slam off Chattanooga’s Jim Kaat, but there was no evidence that Coleman knew what was coming.7

When baseball’s investigators questioned the Lookouts in Nashville, pitcher Jim Heise revealed that Levan had approached him twice suggesting he could “make a little money” by serving up fat pitches. Heise said he declined. Another pitcher, 22-year-old lefthander Tom McAvoy, testified that Levan had asked him whether “he would like to throw a game.” McAvoy said he thought Levan was joking.8

Now Levan was called into the room. Under questioning, he first denied Sammy Meeks’ accusations, but acknowledged that he had introduced Chattanooga players to “an individual unknown to him, but obviously a gambler. …. Levan was to receive an unstated amount of money for his services.” He insisted he never got any money and “he knew nothing of any program to throw games by the deliberate tipping of signs.” (A stenographer recorded the interrogation; the paraphrases come from National Association President George Trautman’s report.)

Levan’s questioners then asked, in effect, “C’mon, you must have known that this gambler wanted to fix games.” Levan replied, “Yes, sir, I’ll agree.” With that, he ended his baseball career.

When confronted by Sammy Meeks, he confessed to a scheme involving signs tipped by Gonzalez, the 25-year-old Cuban shortstop. Gonzalez, now called before the investigators, admitted that Levan had discussed the idea with him, but denied taking part.9

After five hours of interrogation, league President Hurth announced that Levan and Gonzalez were suspended indefinitely for “failure to report a bribery attempt by a gambler.” But he said there was no evidence that either man took any money. The case was forwarded to the National Association for a final ruling.10

The suspensions prompted several sportswriters to ask questions about gambling in Southern Association ballparks. One anonymous player told the Dallas Times-Herald that Chattanooga’s Engel Stadium was “nothing but a gambling casino.” Other writers told of gamblers in the stands who made small bets on whether a player would hit a fly ball or a foul ball. Bob Christian of the Atlanta Journal reported that the case “could be just one scratch on the surface of gambling activities involving Southern Association players.” An unnamed player told Christian that men on just about every team took money to deliberately hit foul balls. Another player, later revealed to be Jack Caro, said he had been offered $700, but turned it down.11

The allegations against Jesse Levan were not about foul balls. On July 30 National Association President Trautman issued his verdict: “For admittedly acting as liaison for a gambler in a program designed to throw Chattanooga games, Jesse Levan is hereby placed on the permanently ineligible list.”12

Waldo Gonzalez was suspended for one year. Trautman justified the lenient sentence because both Levan and Gonzalez testified that Gonzalez refused to pass the signs.13 Trautman did not discipline any other players because they had told the truth.

Levan was the first player to be banned for life since 1948, when pitcher-manager Barney DeForge of the Reidsville Carolina League club became the only man convicted in court of fixing a game. (North Carolina was one of the few states where that was a crime.)14 Later in 1959 former major-league and Southern Association catcher Joe Tipton decided to clear his conscience and admitted he had received $125 after Levan persuaded him to foul off pitches. Tipton was out of baseball, but he was banned for life.15

Trautman’s detailed public statement conceals more than it reveals. The statement records nothing beyond what the players said. There is no indication in the public record that Levan or anyone else was asked to name the gambler. Nor was there any reported effort to examine Levan’s bank accounts to determine whether he took money. In fact, Trautman’s ruling was written to reassure the public that Levan was merely a lone rogue, if a stupid one. Trautman asserted that after “intensive” questioning, all other Chattanooga players were judged innocent. He declared, “No proof was obtained at this hearing, or elsewhere as the investigation progressed, that a game or games had actually been ‘thrown.’”16 If the investigation did progress “elsewhere,” Trautman’s statement does not say where or how. (In 2006 a spokesman for Minor League Baseball told the author that the stenographic transcript of the investigation no longer existed.)

Levan denied the charges. “If Meeks was approached, he was approached by a gambler. I did not approach him,” he said. “I have never been a contact man for any gambler who tried to throw Chattanooga games, as I understand I have been charged. … I never approached anybody with a proposition to throw a Chattanooga ballgame.” He said he would hock his car to hire a lawyer and appeal his life suspension. An appeal was a vain hope; Commissioner Ford Frick had already commented, “It looks as if they had them dead to rights.”17

The banishment of Levan had its “say it ain’t so” moment. That was the headline above a UPI story in the August 2 Atlanta Journal: “Say It Ain’t So, Jesse.” It recounted how 10-year-old Lookouts batboy Bo Short, vacationing with his family in Daytona Beach, Florida, learned of his favorite player’s disgrace. “It’s like a bad dream,” he told UPI, “choking back tears.” Bo had gone to spring training with his father, Chattanooga Times sportswriter George Short, and Levan had helped him with his homework: “He told me I had to study my lessons and do the right thing.”18

The scandal also produced the ritual hand-wringing. The Chattanooga Times reported, “The FBI is on this case.”19 The Chattanooga district attorney asked for a transcript of the ballplayers’ testimony. A Mobile newspaper called for a grand-jury investigation. Atlanta Journal reporter Bob Christian was invited to tell what he knew to a Georgia grand jury.20

No further reports on those investigations ever appeared. In its year-end roundup of baseball activities during 1959, The Sporting News dismissed the affair as “a blown-up gambling scandal in the minors that promised to shake the foundations of the game yet proved relatively insignificant. … [T]he probe led to the uncovering of little gambling activity and that directed to betting on foul balls.”21 Baseball’s establishment had deftly swept the dirt under the rug.

Decades later teammate Roy Hawes recalled, “I never knew anything for sure but some things would happen that made you wonder. Once I had to chase down a throw in left field that Levan threw towards second but missed by a mile. I can’t say he did it on purpose, but again it was one of those things that make you wonder. …. Only two players were suspended, but there were several players who might have been involved.” In 1989 Levan told a reporter, “Others in the league were involved. Their case broke prematurely. It wasn’t what (the investigators) thought it would be and somebody had to get hung for it.”22

Not that gambling and baseball were strangers, 40 years after the Black Sox and 30 years before Pete Rose. The Sporting News published the Las Vegas betting line on the 1960 major-league pennant races: Yankees, 4-5; Braves, 7-5. In July 1960 Chicago police arrested 20 bleacherites in a gambling raid at Wrigley Field. The “Baseball Bible” reported, “Hundreds of dollars were wagered, sometimes just on the umpire’s calls on balls and strikes.” Commissioner Ford Frick had called the cops after finding that “gambling conditions at the Cubs’ park were among the worst in the majors.” There were many other published reports of police raids on gamblers in major-and minor-league parks in the 1940s and 1950s.23 In 1963 the general manager of the Class A Nashville Vols, veteran executive Ed Doherty, warned the team’s broadcaster not to comment on the gamblers circulating in the stands.24 But no other player has since been implicated in game-fixing. As the minors contracted and came under control of their major-league parents, there was less room for lifers like Levan—veterans with no hope of advancement.

Deprived of the livelihood he had pursued since he was 17, Levan returned home to Reading with his wife, Gerry, the former Geraldine Hudson. They had two sons and three daughters. He worked for 23 years driving a meat truck for Berks Packing Company before retiring in 1988. He also coached church-league softball teams.25 In 1996 he was honored as a baseball legend in a ceremony at Reading’s Municipal Stadium. He told the Reading Eagle-Times,“I feel I had a great career. I got to the big show and, but for injuries, I know I could hit at all levels of competition.”26 The next year he was inducted into the Berks County chapter of the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame. Contemporary stories in the local paper recounted the highlights of his baseball career, but did not mention how it ended. His neighbors were evidently willing to forgive and—most important—to forget.

After suffering two strokes, Jesse Levan died at 72 on November 30, 1998.

Sources

Portions of this story are adapted from “Why, They’ll Bet on a Foul Ball: The Southern Association Scandal of 1959,” by Warren Corbett. SABR’s The National Pastime, No. 26 (2006), pp. 54-60.

Mike Drago of the Reading Eagle and SABR members Rebecca Rishar, Bill Mortell, and Merritt Clifton contributed information.

Major-league game accounts from retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Richard Flannery, “Hitting Machine,” Reading Eagle-Times, Aug. 12, 1996, pp. S1-2.

2 St. Petersburg Times, Sept. 16, 1952, p. 10.

3 Washington Post, March 30, 1955, p. 29.

4 Ibid.

5 David Jenkins, Baseball in Chattanooga (Arcadia Publishing, 2006), p. 52.

6 Chattanooga Times, July 31, 1959, p. 31. The Times printed the Associated Press transcript of National Association President George Trautman’s July 30 ruling in the case, hereafter cited as “Trautman ruling.”

7 Ibid. and Chattanooga Times, August 1, 1959, p. 12.

8 Trautman ruling.

9 Ibid.

10 Chattanooga Times, July 4, 1959, p. 1.

11 Associated Press, Washington Post, Aug. 19, 1959, p. C4; Atlanta Journal, July 28, 1959, p. 10 and Nov. 14, 1959, p. 6.

12 Trautman ruling.

13 The Sporting News, Aug. 5, 1959, p. 23. The Associated Press text of Trautman’s ruling, published in the July 31 Chattanooga Times, reads, “…both Levan and Gonzalez testified that he actually did pass signs to certain Mobile batsmen.” I accept The Sporting News’ version (“did not”) because it is consistent with the rest of the ruling. If Gonzalez admitted “that he actually did pass signs,” leniency would not have been justified.

14 UPI, New York Times, July 31, 1959, p. 15; on DeForge: The Sporting News, July 9, 1948, p. 5.

15 The Sporting News, Nov. 25, 1959, p. 6.

16 Trautman ruling.

17 UPI, New York Times, July 31, 1959, p. 15; Chattanooga Times, Aug. 1, 1959, p. 11.

18 UPI, Atlanta Journal, Aug. 2, 1959, p. D1.

19 Chattanooga Times, July 7, 1959, p. 11.

20 The Sporting News, Sept. 2, 1959, p. 22; Associated Press, Atlanta Journal, Aug. 1, 1959, p. 11; AP, Chattanooga Times, July 31, 1959, p. 31.

21 The Sporting News, Dec. 30, 1959, p. 5.

22 Jenkins, Baseball in Chattanooga, p. 53.

23 The Sporting News, Nov. 17, 1959, p. 7, and Aug. 3, 1960, p. 28. Curiously, stories about ballpark gambling vanished from The Sporting News after 1960. Whether the paper decided to stop reporting them, or whether police decided they had better things to do, cannot be determined.

24 The author was the broadcaster.

25 Reading Eagle, Dec. 2, 1998, p. 20.

26 Flannery, “Hitting Machine.”

Full Name

Jesse Roy Levan

Born

July 15, 1926 at Reading, PA (USA)

Died

November 30, 1998 at Reading, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.