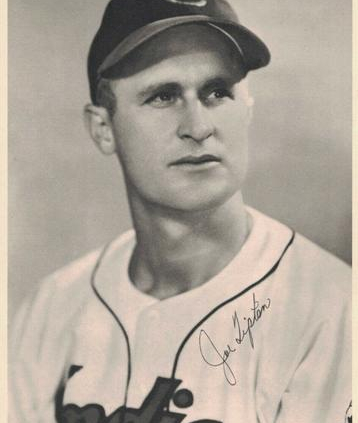

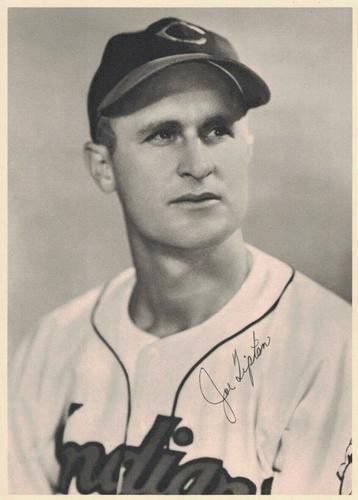

Joe Tipton

If “Who was Joe Tipton?” was the answer on Jeopardy!, the writers might have struggled to provide the clue. Perhaps only the savviest of baseball fans would be able to recall the backup catcher of seven seasons in the majors.

If “Who was Joe Tipton?” was the answer on Jeopardy!, the writers might have struggled to provide the clue. Perhaps only the savviest of baseball fans would be able to recall the backup catcher of seven seasons in the majors.

Tipton’s seven years, all in the American League, were highlighted by 1948. In his rookie season with Cleveland, Tipton served as the second-string catcher behind Jim Hegan. The Indians were crowned World Champions that season; as of 2022, the franchise has yet to replicate that feat.

After that season, Tipton donned the “tools of ignorance” for the Chicago White Sox (1949), Philadelphia Athletics (1950-1952), Cleveland again (1952-1953), and Washington (1954).

In 1959, Tipton admitted to consorting with known gamblers two years prior as a member of the Birmingham Barons of the Southern Association. As a result of his admission, he received a lifetime ban from minor-league baseball.

Joseph Hicks Tipton was born on February 18, 1922, in McCaysville, Georgia. He was one of seven children born to Charles Burton “Burt” Tipton and Nola (née Leatherwood). Burt worked as a repairman in a manufacturing plant that produced sulfuric acid.1 Nolie, as homemaker, kept the order in the Tipton household.

McCaysville is in Fannin County, on the northern border of Georgia, just below Tennessee. Its sister city, directly across the state line, is Copperhill, Tennessee. Copperhill, in Polk County, is situated in the southeast corner of the state. The Tipton family settled there.

There were other athletes in the family. Joe’s eldest brother, Earl, played Class D baseball in 1938, but his career was cut short by injury. By one account, the youngest Tipton child, Dorothy, was the most athletic of all. Dot became a member of the Fannin County Sports Hall of Fame in 2015.2

Although Tipton never played baseball at Copperhill High School, he did make a name for himself on the sandlots around McCaysville.3 Tipton’s primary position was shortstop when he was discovered by Cleveland scout Art Decatur.

Tipton began his professional journey in 1941. He started out with the Flint Arrows of the Class C Michigan State League. In 10 games, Tipton batted .364. However, he was a player without a position. On June 18, and to get more playing time, Tipton was optioned to the Appleton Papermakers of the Class D Wisconsin State League.4 He was put in the outfield, at third base, and occasionally catcher. Between the two clubs, Tipton batted a respectable .307.

Jack Knight, a former pitcher in the National League with St. Louis and Philadelphia, was Tipton’s manager at Flint. When Tipton moved up to the Charleston Senators of the Class C Mid-Atlantic League in 1942, Knight was his skipper again. “In my opinion, about the best thing that can happen to a rookie is to go to work for a fellow like Knight,” said Tipton. “He had more confidence in me than I had in myself. It was Jack who decided that I ought to switch to catching.”5

Although Knight may have suggested the position change to Tipton, the skipper placed Tipton primarily in the outfield. Tipton continued to hit well. He batted .313 in 262 at-bats for Charleston.

World War II was in full force in 1942. Tipton enlisted in the United States Navy on February 18, 1943.6 For the next three years, Tipton served aboard the escort carrier USS Kadashan Bay in the Pacific Theater of Operations. The carrier was involved in three battles: The Leyte Gulf in 1944, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.7 At Leyte Gulf, the pilots of the Kadashan Bay spotted the Japanese Central Force sneaking up on a group of American ships. The carrier ship launched planes and torpedoes in support of the “Taffy 3” task unit against the Japanese Central Force. Although they were outnumbered, the Americans were decisive victors in what became known as the Battle of Samar.8

Tipton was discharged on October 10, 1945.9 “When I came back for the 1946 season, I knew I would have to work harder than ever,” he said. “I had been off the diamond so long and I was still green as grass as far as catching was concerned.”10

Over the next two years Tipton continued his ascent through Cleveland’s farm system. At Class B Harrisburg, he split time behind the plate with Ed Mutryn. His days in the outfield were not over – manager Les Bell still employed Tipton “in the garden” when he was not behind the plate. He played in 104 games, batting .327.

On March 24, 1947, Tipton married his high school sweetheart, the former Reva Jean Earls. They had three children: daughter Kathryn and sons Charles and Barry.

The following season at Class A Wilkes-Barre, Tipton was used solely as a catcher. Manager Bill Norman empowered Tipton to call his own game, to handle the pitchers as he saw fit. The maturation of Tipton as a full-time backstop appeared complete. Not only did he field his position at a .982 clip, he also led the entire Eastern League in batting with a .375 average, 13 percentage points ahead of Utica outfielder Richie Ashburn.

Mike McNally, general manager of the Wilkes-Barre club, suggested that the Indians give Tipton a look at spring training in 1948. Veteran catcher Al Lopez had played his last in the majors, so Cleveland needed a new backup for Jim Hegan. Though Hegan was considered one of the better defensive catchers of his era, he was not much of an offensive threat. Provided Tipton could hit major-league pitchers, he could add offense to the catcher position.

Tipton made his big-league debut against Detroit on May 2, 1948, at Cleveland Stadium. Hegan was replaced by pinch-hitter Wally Judnich in the bottom of the eighth inning. Tipton then caught the ninth frame. Detroit toppled the Tribe, 4-2.

On May 30, Tipton started the first game of a doubleheader against Chicago at Comiskey Park. The rookie went 3-for-3 with a walk. In the second game, he was called on as a pinch-hitter, and was plunked in the hand by Sox pitcher Earl Harrist.

He next started on June 6 in the second game of a twin bill at Shibe Park. In this game, Tipton went 5-for-5. Tipton’s name was next written on manager Lou Boudreau’s lineup card on June 10 at Fenway Park. He singled in the third inning. He flied out in his next time up in the fifth inning. Beginning with the doubleheader on May 30, Tipton had reached base in nine consecutive at-bats, with one walk. The club record is 11, set by Tris Speaker in 1920.

Tipton started at catcher 19 times for the Indians in 1948. In 39 total games behind the plate, he batted .310 with one home run and 11 RBIs. He went 0-for-6 in eight pinch-hitting appearances to lower his overall batting average to .289.

Cleveland ended the season tied with Boston, both posting identical 96-58 records. On October 4, 1948, at Fenway Park, the Indians and Red Sox faced off in the first playoff game in American League history. Cleveland beat the Red Sox, 8-3. After the game, the team celebrated at the Kenmore Hotel. A fight ensued between Tipton and Ken Keltner, with Joe Gordon, Eddie Robinson, and several others jumping into the fray. Red noses and small cuts were evidence of the horseplay. “I really had a fat lip the next morning and I couldn’t eat much for the next couple of days,” said Tipton. “Several of the fellows got involved and nobody seemed to know just who started it.”11

However, Tipton admitted that he was the initial instigator of the ruckus. “I’m certain that trouble in Boston was a factor when Bill Veeck got rid of me the following winter,” he later said.12

The Indians remained in Boston and faced the NL pennant-winning Braves in the World Series. Tipton’s only appearance in the series was in Game Five on October 10. He pinch-hit for pitcher Bob Muncrief and struck out to end the game.

Cleveland won the series in six games, capturing the championship at Braves Field on October 11. It was the second title in franchise history.

As Tipton alluded to years later, Cleveland traded him. On December 4, 1948, he went to Chicago for pitcher Joe Haynes. White Sox manager Jack Onslow named Tipton the team’s starting catcher.

Their relationship soured, however, after a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns at Sportsman’s Park on May 1, 1949. Don Wheeler caught the opener, a 7-6 Chisox victory. Tipton was behind the plate for the nightcap. The visitors led 14-3 after eight innings. Tipton was one of the hitting stars, going 3-for-5 with a triple, two RBIs, and a run scored.

Onslow blew up when the Sox surrendered eight runs in the bottom of the ninth. Although the Browns lost, 14-11, Onslow was upset that his team allowed that many runs in one inning. He put some of the blame on Tipton and his pitch selection. “I was ashamed of the way we played in that final inning,” said Onslow.13

One word led to another between catcher and skipper, and a ruckus ensued. However, Onslow at 60 years old was not about to take on the 27-year-old Tipton, and cooler heads prevailed. Wheeler was inserted as the number-one catcher while Tipton cooled his heels in Onslow’s doghouse.

One of the highlights for Tipton occurred on June 23 when he belted two home runs against the Philadelphia A’s at Shibe Park. Unfortunately, the round-trippers had little impact as the Athletics were victorious, 11-4.

Tipton, Wheeler, and Eddie Malone split the catching duties for the 1949 White Sox. Of the three, Tipton was the least effective with the lumber, batting .204 with three home runs and 19 RBIs.

The A’s traded backup catcher Buddy Rosar to the Red Sox on October 8, 1949. They then dialed up Chicago general manager Frank Lane to inquire about the availability of Tipton. Whether the tiff between Tipton and Onslow had any bearing on the deal is anybody’s guess. “Trader Frank” made one of his shrewdest deals on October 19 when he sent Tipton to the A’s for utility infielder Nellie Fox.

Neither front office could envision the career on which Fox would embark. Chicago already had All-Star Cass Michaels at second base. Michaels was another player who did not get along with Onslow. But neither player nor manager was with the Chisox at the end of May, and Fox stepped right into the keystone position. Connie Mack had ranked the selling of pitcher Herb Pennock to the Boston Red Sox in 1915 as his biggest baseball mistake. The trading of Fox to Chicago surpassed the Pennock transaction.14

Tipton was noted as having a volatile personality, which may have stemmed from his scuffles. However, he was also characterized as being a hard drinker. Indeed, the A’s newest backstop showed up at spring training with a footlocker containing mason jars filled to the brim with “white lightning” moonshine.15

Mack paired Tipton with pitcher Lou Brissie to provide the catcher with a positive influence. However, Brissie did not rub off on Tipton, who invited teammates to their room for “tastings.”16

Another facet of Tipton’s personality was his constant jabbering at the opposing batters. One of his favorite foils was Ted Williams. Tipton would attempt to get in Williams’ head when he stepped into the batter’s box. “Ted, you’re swinging too hard,” or “Ted, you’re topping the ball,” or he was swinging late or too early.17 Williams tired of Tipton’s harassment, telling A’s coach Bing Miller, “I am certainly glad to see the Athletics leave town,” said Williams. “And don’t forget to take Tipton with you.”18

Tipton was the second-string catcher on the 1950 A’s, backing up Mike Guerra. Tipton found his hitting stroke, batting .266 and establishing a career-high with six home runs. Bob Hooper (15-10) was the only starting pitcher on the team to reach double-digit wins and post a winning record in 1950. Philadelphia finished in the cellar of the American League with a 50-102 record, 46 games behind first-place New York.

In the offseason, Philadelphia sold Guerra to the Red Sox for $25,000. As a result, Tipton was promoted to starting catcher in 1951. However, he was sidelined by injuries. He received a concussion as the Browns’ Ray Coleman swung the bat on May 15; he didn’t get into a game again until May 26. He later suffered a contusion on the instep of his left foot from a batted ball on July 19. Nonetheless, Tipton started the most games (69) at catcher, while Joe Astroth (50) and Ray Murray (35) both saw plenty of action. The starting pitching improved, and after the team traded for Gus Zernial on April 30, he proceeded to lead the league in home runs (33) and RBIs (129). The A’s (70-84) won more in 1951 but still finished in sixth place.

Following the season, Joe DiMaggio managed a team, made up mostly of players from the AL, that toured Japan and played 15 exhibition games beginning on October 20 in Tokyo. Tipton was on the roster, along with A’s teammates Bobby Shantz and Ferris Fain.

Tipton got off to a slow start in 1952. He was batting .191 in June 23 when the A’s sold him to Cleveland for the $10,000 waiver price.19 “Maybe this is a break for me,” said Tipton. “Maybe I’ll get enough work – and enough lucky hits – to convince them I should get a raise.”20

Jim Hegan had been nursing a sore leg, necessitating the deal. Maybe, as Tipton had speculated, it was the change of uniform, but Tipton found his hitting stroke almost right away. On June 29, in the second game of a doubleheader at Comiskey Park, he belted two home runs and drove in four runs as the Chisox and Tribe battled to a 7-7 tie in a game called after 10 innings on account of darkness. On July 31, the Indians and Red Sox were knotted at 2-2 when the Tribe scored six runs in the bottom of the eighth inning to break the game open. The first two scored on a home run by Tipton, for which the Indians receiver gave credit to third base coach Tony Cuccinello. “Tony called the pitch,” said Tipton. “All I had to do was swing that bat. With a 3-2 count I had (Mickey) McDermott in the hole and he came in with that fastball right down the pipe. Thanks to Tony, I was waiting for it.”21

Between the A’s and the Indians, Tipton set career highs in home runs (9) and RBIs (30). He continued to back up Hegan with Cleveland in 1953. Then, in a trade of second-string backstops, Tipton was dealt to Washington for Mickey Grasso on January 14, 1954. He finished his big-league playing days as a member of the Senators in 1954, spelling Ed Fitz Gerald.

In seven years and 1,117 at-bats, Tipton batted .236 with 29 home runs and 125 RBIs. Along with his .984 fielding percentage as a catcher, he showed a strong and accurate arm in his limited duty, with a 56% caught stealing rate (though the stolen base was not in favor as a strategy during his career).

Washington sold Tipton to Minneapolis of the American Association. But the Millers dealt him to the Memphis Chickasaws of the Southern Association. Although he was thought to be the best catcher in the league, Tipton was given an indefinite suspension for insubordination. On July 18, he got into an argument with manager Jack Cassini. “I could not tolerate the way Tipton talked to me in front of my players,” said Cassini. “He bawled me out before the players and I’m not going to let anybody tell me off.”22

Tipton returned to his home in McCaysville, where he owned a gas station. He did not play in 1956. However, his contract was purchased by Birmingham, also of the Southern Association. Tipton, at 35 years of age, agreed to report to the Barons.

While with the Barons, Tipton was approached by Jesse Levan, first baseman for Chattanooga. Levan persuaded Tipton to take part in a scheme where he would be paid for hitting foul balls. Although this practice was not “throwing games” or changing the outcome of a game, known gamblers were still involved and the players received payoffs.

“Gamblers wanted batters to deliberately foul off,” said George Trautman, President of the National Association, in November 1959. “This being prearranged so the gambler, knowing certain batsmen would attempt to foul off pitches, would be in a position to profit on bets he would make with individuals who did not possess that knowledge.”23

On two occasions when Birmingham was playing at Chattanooga, Tipton received compensation. One payment he received was for $50 and the other was for $75. The second payment was mailed to his home. By the time the matter came to light, Tipton was retired from baseball and could not be compelled to testify. However, he wanted to clear his conscience. Trautman handed down a lifetime ban from minor-league baseball to both Levan and Tipton.

Tipton remained a resident of Birmingham and worked as a car salesman for a Ford dealership. He passed away from an undisclosed illness in Birmingham on March 1, 1994. Tipton is buried at Pleasant Grove Methodist Cemetery in Pleasant Grove, Alabama. He was survived by his wife Reva, three children, two sisters, and a brother.

In an interview in 1974, Tipton recalled his most vivid memory from his playing days was being a member of the 1948 Cleveland Indians and playing for two wonderful people: Lou Boudreau and Bill Veeck.24

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by W. H. Johnson.

Notes

1 1930 United States Census.

2 “Dot Tipton Hardeman,” Fannin County Sports Hal of Fame website, unknown date in 2015 (http://www.fcshof.com/2015-inductees/dot-tipton-hardeman/)

3 Ed McAuley, “Joe Tipton, Top Hitter of Eastern League, Backs Tribe Backstop Bid with Bludgeon,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1948: 11.

4 Maurlo Cossman, “Flint Campaign for Lead on July 11 is Succeeding,“ The Flint (Michigan) Journal, June 19, 1941: 37.

5 McAuley.

6 Joe Tipton’s military record on Ancestry.com. Accessed November 24, 2022.

7 Biography of Joe Tipton, Baseball in Wartime website: https://baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/tipton_joe.htm Accessed November 24, 2022.

8 www.hullnumber.com, https://www.hullnumber.com/CVE-76 Accessed November 24, 2022.

9 Tipton’s military record.

10 McAuley.

11 Joe Tipton, “Tipton Calls Punch at Keltner ‘mistake,’” Tipton’s Newspaper Clipping File, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

12 Tipton file.

13 Jack Ryan, “No Fines After Row: Onslow,” Chicago Daily News, May 2, 1949: 21.

14 Norman Macht, The Grand Old Man of Baseball: Connie Mack in His Final Years, 1932-1956 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 446.

15 Macht, 447.

16 Macht, 477.

17 Art Morrow, “Lady Luck Two-Times A’s: Fain Back, Tipton Goes Out,” The Sporting News, August 29, 1951: 10.

18 Morrow, 10.

19 The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote in the June 24 edition that Tipton was batting .176. Retrosheet had his average at .191.

20 Art Morrow, “Indians Get A’s Tipton,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 24, 1952: 35.

21 Charles Heaton, “Tipton Says Cuccinello Called Home-Run Pitch,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 1, 1952: 12.

22 Will Carruthers, “Joe Tipton Draws Chick Suspension,” Memphis Press-Scimitar, July 19, 1955: 15.

23 “Joe Tipton is Banned from Baseball for Life,” Chicago Tribune, November 16, 1959: 2-1, 2-6.

24 Dennis Lustig, “Whatever Happened To…?” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 26, 1974: C-1.

Full Name

Joe Hicks Tipton

Born

February 18, 1922 at McCaysville, GA (USA)

Died

March 1, 1994 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.