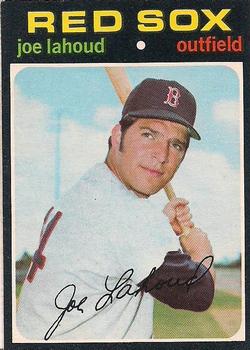

Joe Lahoud

Signed to the Boston Red Sox by Frank “Bots” Nekola, the same scout who signed Carl Yastrzemski, outfielder Joe Lahoud faced some stiff competition trying to break into the majors. At the time, his path intersected with those of both Yaz and local Boston favorite Tony Conigliaro.

Signed to the Boston Red Sox by Frank “Bots” Nekola, the same scout who signed Carl Yastrzemski, outfielder Joe Lahoud faced some stiff competition trying to break into the majors. At the time, his path intersected with those of both Yaz and local Boston favorite Tony Conigliaro.

Lahoud came from Danbury, Connecticut, born there on April 14, 1947, to parents Marguerite Nichols Lahoud of Dover-Foxcroft, Maine and Joseph Michael Lahoud Sr. “My mom was born and raised in Maine. My father met her when he was in the service at Fort Devens. My mom comes from Irish heritage and descent. My father was from Lebanese background. He was born in Lawrence, Mass. but his father’s mom and dad were full-blooded Lebanese who migrated here.” Joe had an older sister, Sharon.

Danbury was well-known at the time as the “Hat City,” and Joe Lahoud Sr. worked as a hatter. “He used to work for the Lee Hat Company and Neuman-Endler in Danbury. He did a few things but his main job was as a hatter. He would take the hats, put them on the cones, and give them to the next person, who would shape the hat and everything.”1

Joe attended the Locust Avenue School, and then high school at Danbury’s Henry Abbott Regional Technical School where he played baseball, basketball, and soccer. Baseball wasn’t his first sport. “I wasn’t that interested in baseball at first. Henry Abbott Tech really didn’t have much of a baseball team. The kids were smoking in the outfield – that kind of crap. So I really concentrated more on my basketball and my soccer, which I enjoyed very, very much. I did play baseball my senior year and I loved the game, but I had multiple scholarships in basketball.”

He was also co-sports editor of the high school paper, The Wolverine.2 After graduation, he was granted a basketball scholarship to New Haven College in West Haven, Connecticut. He was just there one year; his father had open heart surgery at the age of 46. Joe had to make a decision as to whether to go back to school or to help pay the bills. “I decided to see what I could do to help pay the bills. I got scouted by Bots Nekola and I took whatever money I could get, which was not much. As I was playing pro ball, most of it was going home to my dad. I was fortunate enough to have some kind of impact and get to the big leagues.”3

The bonus was reported at the time as $2,500 and Joe started playing professional baseball in the fall of ’65.4

He’d had the opportunity to play some competitive baseball before completing high school, though, in the Merchants League. “You had to be 19 and over, and I was only 16 but I lied about my age and I played in that league. It was old Lee’s Field in Danbury and they had these really old lights, but we could never raise enough money to put the lights on. My dad subsidized paying for the lights, and then we finally got some of the merchants to start chipping in. We put together a pretty good team and we started playing not just locally but other teams across the state. The Merchants League grew to become a tri-state league – Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey. That was fun.”

Lahoud was signed in the summer of 1965 and assigned to Sarasota in the Florida Instructional League. The team included George Scott, Reggie Smith, Billy Conigliaro, and Bob Montgomery, and was managed by Eddie Popowski. Both Bobby Doerr and Nekola were on the staff. Lahoud, an outfielder, played in 45 games. He hit .170 with only six runs batted in, but he was just 18 years old.

In both 1966 and 1967, Lahoud played in Single-A ball for the Winston-Salem Red Sox (Carolina League). In ’66, he played in 62 games, hit for a .261 batting average with 25 RBIs. He would have played longer but for a broken ankle in late June that cost him most of two months. In ‘67, at age 20, he hit .287 in 99 games (with a .406 on-base percentage) and drove in 62 runs, with 16 homers. That winter he went back to instructional league and played in another 26 games, but only hit .216. He served in the Army National Guard for a while in 1966 and 1967, but his time was reportedly cut short due to flat feet.5

In 1968 he opened the season with the Boston Red Sox. He’d impressed in his very first at-bat in spring training, hitting a home run over the 30-foot center-field wall in Bradenton, which was 430 feet from home plate. Larry Claflin of the Boston Record-American wrote that he was the first batter to ever clear the wall.6 John Gillooly said that “the fence was so far from the plate that it was visible only on smogless days.”7 He got two hits the next day, and another two (with two RBIs) the day after that. Red Sox manager Dick Williams said, “I don’t believe what I’m seeing, but I am going to keep the kid in there.”8

Coming off the pennant-winning “Impossible Dream” season, sportswriter Fred Ciampa noted that Lahoud faced a major challenge: “Trying to crack an outfield of Carl Yastrzemski, Reggie Smith, and Tony Conigliaro is an impossible dream in itself.”9 Tony C. worked out in spring training, but during the first week in April it became clear that he would be unable to play in 1968 due to eye problems that were lingering effects of his horrific beaning in August 1967. Lahoud, who had been sent to minor-league camp at Deland in the first cut, was recalled to Winter Haven and given a shot at the right-field job.

Lahoud batted and threw left-handed. He was 6-foot-1 and listed at 198 pounds.

He was, of course, being thrust onto the main stage without the experience and grounding that minor-league training provides. He was, as a Sporting News headline explained, jumping ahead of the planned schedule for his development. There was a need, but as Dick Williams said from the start, “I will not keep him around and sit him on the bench.”10

In his major-league debut on April 10 in Detroit, Lahoud walked (and scored) his first time up, singled his second time at bat, then drew two more walks. He was solid on defense, with “two consecutive circus catches. On flies to right field that were spiralled (sic) by the wind and inflamed by the sun.”11 “You can’t do much better than he did out there today,” said manager Dick Williams.12 The next day, he finally made an out, striking out his first time at bat, but walked his second time up, and then hit a two-run homer into the upper deck of Tiger Stadium off Denny McLain. Dick Williams was never one to let his players get off easy, though. He griped about Lahoud’s “failure to execute a bunt play” in the eighth inning.13

After 11 games, batting .206, he was sent down to Louisville at the very end of April. He was disappointed, of course, but Yaz had some words of wisdom conveyed through the press: “He should be glad. He shouldn’t want to be platooned at his age. He has a great future.” Eddie Popowski added, “He’s down now, but he won’t stay down.”14

That prophecy proved true when both Ken Harrelson and Jose Tartabull suffered injuries in early June. He played in the majors for most of the month of June and was then sent back to Louisville. He was batting .192. Lahoud was upset about being sent down the second time; he would, he said, rather have stayed there for the full season so he could fully get on track.15 With Louisville, in the two stints, he got regular work, playing in 101 games and batting .273.

In 1969, Lahoud spent the full season with Boston. He played in 101 games, but only hit for a batting average of .188. Tony Conigliaro had a comeback year, appearing in 141 games, but Lahoud served as the primary fourth outfielder. It looked to be a tough outfield to try to break into – with Yaz, Reggie Smith, and Tony C. “No team in baseball has the outfield talent and depth that we have,” said Dick Williams.16

Lahoud was impatient. “Everybody tells me, “Hey, Joe, you’re only 22 and you’re already in the majors. Live with it a couple of years, you’ll get your chance.” But they don’t have to sit on the bench. Maybe they don’t think I’m ready yet. But I do.”17 He said he was taking infield practice, and he’d be glad to catch if it got him in the lineup on a regular basis. His father, he said, had calculated that in games Lahoud started, he was hitting .290.

He did not get the regular work he sought, but he was the fourth man. Don Lock and Tony’s brother Billy Conigliaro also put in time in the outfield. In most of the games, he came in during the game as a pinch-hitter or defensive replacement, but he did have over 40 starts. His eye at the plate saw him secure 40 bases on balls to go with his 41 base hits, and thus achieve an on-base percentage of .317.18 He drove in 21 and scored 32. By far his biggest day was on June 12 in Minneapolis when he came into the game batting .083 and hit three home runs, driving in four runs. All three homers were hit into the right-field bleachers, and each was off a different pitcher. At the time, Ted Williams was the only left-handed Red Sox batter to have homered three times in the same game. One of his most welcome homers was on July 27, a two-run homer in the top of the 20th inning in Seattle. But he didn’t get the regular work he wanted. “I played a lot in the eighth and ninth innings and you can’t get your hits unless you see a pitcher three or four times in a game.”19

Later, Gerry Finn of the Springfield (Massachusetts) Union characterized the role Lahoud had performed as the fourth or fifth outfielder during his time in Boston, writing that he “babysat for pulled-muscle regulars.”20

Late in the season, he told Boston Herald columnist Laura White, “I feel I have the potential of a superstar, if I could only get to play regularly.”21 White’s article was one of a series on “Eligible Bachelors” and offers Lahoud’s thoughts on family and dating at the time.

He had no lack of confidence. “I’m fairly confident I can hit 30 home runs and bat .300 in the major leagues. I just want to play every day.”22 Billy C wasn’t buying it. Talking about Lahoud, he complained, “Not many guys can bat .180 and still play. I’m a better fielder than he is. I think I’m a better all-around ballplayer.”23

There wasn’t a lot of love lost between Billy C and Joe Lahoud. “We had a few fights, drag-outs where they had to pull us apart,” Lahoud told Peter Golenbock. “I remember one time getting cold-cocked in the back of the head.”24

Lahoud spent most of 1970 in the minors, with Louisville. He hadn’t been pleased when sent down, saying he hadn’t been given a fair shot in the springtime and blaming it on “politics.”25 It was perhaps not so much politics, as business: he had an option left. He’d been hoping to serve as a fourth outfielder, but it wasn’t in the cards. But Billy Conigliaro was ready, and indeed proved himself during the season. Lahoud said he hoped he’d be traded; he knew that at least a couple of teams were interested.26 He was ready to put in another year in the minors, if need be. He was astute enough to know that then the Sox would be out of options; they’d have to keep him on the big-league team in 1971 or trade him.27 They actually did both, but the trade came after the season.

Lahoud benefitted from a full year with Louisville in 1970, playing in 136 games and batting an even .300. He worked 116 walks to go with his 136 base hits, and compiled a .441 on-base percentage. He drove in 93 runs. He was brought up to Boston in September and hit a creditable .245 in 17 games for first-year manager Eddie Kasko.

In 1971, Lahoud was limited to pinch-hitting and late-inning roles until mid-June. He reportedly “maintained a remarkable silence and calm while not playing” and even in the limited action he was batting over .300. He homered three games in a row on a West Coast swing, and then played regularly after that. Billy C (101 games, batting .262) and Lahoud (107 games) shared duties, but Lahoud’s average tailed off as the season wore on, and he finished batting only .215. His standout game was at Fenway Park on the Fourth of July, with two homers and three runs batted in helping to beat the visiting New York Yankees.

After the season was over, the Red Sox didn’t choose between them. They traded both of them, together. Billy Conigliaro had worn out his welcome, feuding with both Carl Yastrzemski and Reggie Smith.28 On October 10, 1971, they executed a 10-player trade with the Milwaukee Brewers, with Ken Brett, Jim Lonborg, Don Pavletich, and George Scott packaged with Lahoud and Billy C, in exchange for Tommy Harper, Lew Krausse, and Marty Pattin, and minor-leaguer Pat Skrable.

Lahoud looked like a throw-in, given his .215 batting average, but Brewers GM Frank Lane had been impressed with his 14 homers in 256 at-bats. For Lahoud, it was an opportunity and he impressed Lane by offering to come to spring training two weeks early, at his own expense.29

He got regular work in 1972, appearing in 111 games, with 363 plate appearances. Despite playing half his games in a park with a much shorter right-field fence, he only homered 12 times, but he pulled his average up to .237.

Lahoud mostly worked as designated hitter and pinch-hitter in early 1973 and had a dismal start. As late as May 17, after 60 plate appearances, he was batting under.100 (.094) and he wasn’t happy. “There is a definite mental adjustment to make as the DH. I just wish he [manager Del Crandall] gave me the chance to do it during the spring…There’s no doubt in my mind,” he said, “that there’s no future here [Milwaukee] for me. I really wish they’d give me my release, but they won’t.”30 He had a really big game on June 16, with two homers (one a grand slam) and six RBIs, but it was an off-year for him and he only drove in 26 runs all year long. His batting average was .204 in 96 games. Near the end of the year, he said, “I don’t enjoy playing for people I don’t respect.”31

He got his wish for a trade, and on October 22 was part of another large group, this time a nine-player trade with the California Angels. It was Lahoud, with Ollie Brown, Skip Lockwood, Ellie Rodriguez, and Gary Ryerson to the Angels for Steve Barber, Ken Berry, Art Kusnyer, Clyde Wright, and some cash.

Lahoud returned to Connecticut for the offseason where he worked for a car-leasing firm and part-time with an uncle in the Lahoud Real Estate Co.32

In 1974, Lahoud had the best year of his major-league career. He played in a career-high 127 games (106 in the outfield) and hit for a career-high .271 batting average. His 44 runs batted in were the most in a big-league season for him. The season had started with Bobby Winkles as manager; Dick Williams managed the last 84 games.

The 1975 season saw Lahoud revert more to the norm. He was hitting .214 with 33 RBIs after his last game of the season, on July 30. He suffered a rib separation. About a week later, he displayed some wry humor and perhaps some acknowledgement that he wasn’t going to be that 30-homer player. “It’s easy to stay in the major for 7 ½ years when you hit .300. But when you hit .216, like me, it’s really an accomplishment.”33

The injury was initially expected to cost him 7-10 days, but he was later put on the 21-day disabled list, and he was unable to return before season’s end. He’d only appeared in 76 games.

In 1976, Lahoud played for two teams. He began the season with the Angels (managed by Dick Williams), but he was only batting .177 in mid-June after 42 games and only had four RBIs. At the trading deadline, his contract was purchased by the Texas Rangers. At the same time, Charlie Finley of the Oakland A’s held his famous fire sale, selling Vida Blue to the Yankees and Joe Rudi and Rollie Fingers to the Red Sox. Before any of the players appeared in a game, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn intervened, held a hearing, and then nullified the sales “in the best interests of the game.”34

Oakland manager Chuck Tanner had protested the sale of Lahoud, arguing, “If Rudi, Fingers, and Blue still belong to us [following the Commissioner’s decision] then Lahoud still belongs to the Angels and that means they have 26 players.”35 He said the unsigned Lahoud was in effect an illegal player with the Rangers.

Things hadn’t been that smooth on the Angels, who had finished last in the AL West for 1974 and 1975. And Dick Williams acknowledged that the ’76 Angels were “a team I could no longer control.”36 He said he wrote off the older players as lost causes and drove the younger players hard; he and coach Grover Resinger yelled at them relentlessly. “We yelled so much,” he wrote, “that when we shipped out veteran Joe Lahoud, he complained, ‘Those two guys ought to be wearing swastikas.’”37

Lahoud’s sale went through and he mostly pinch-hit and DH’d for the Rangers. In 101 plate appearances, he hit .225 and drove in five runs.

He reported to spring training with the Rangers but on arrival was told that he didn’t figure in their plans. Hearing that, he asked for his release, but it was denied. He was told they hoped they might be able sell his contract for a little more than they would get by placing him on waivers. His reaction was to say, “In all my years in baseball, both the majors and minors, I’ve never been treated as poorly by any team. If they don’t want me, that’s all right with me. But at least they could give me a release so I could try to find somebody who does want me.”38 Perhaps the public airing of his grievance helped; he was released about two weeks later, on March 14.39 And on March 22, he signed as a free agent with the Kansas City Royals.

The Royals placed him with their Triple-A team in Omaha (American Association). There he played in 84 games, and he had a very successful season, batting .317, with 19 homers, and driving in 69 runs. He had seven game-winning hits. He also earned the appreciation of 19-year-old Clint Hurdle, who said, “I was having, my problems early until Joe started helping me. He spent a lot of time with me.” When Lahoud heard that, he said, “When I was 18 the greatest hitter of them all, Ted Williams, took time to work with me. I went to the instructional league and we were supposed to report at 9:30 A.M. Williams said, ‘Kid, if you want to learn to hit, be here at 7:30 tomorrow…7:30 in the morning.”40 He said Williams worked with him for two hours in the morning and then two more hours after everyone left in the afternoon, something he did for days.41

Though he admitted he’d rather be drawing a big-league salary, he seemed content, telling the Omaha World-Herald at the end of June, “I’m playing every day and I really enjoy it, but if I go up I don’t think I’ll be playing. All I’d probably be doing is pinch-hitting.”42

On July 15 he was called up to Kansas City. Manager Whitey Herzog used Lahoud in a mix of ways – sometimes pinch-hitting, sometimes playing full games, sometimes as a late-inning replacement. In 34 games, he had 77 plate appearances and hit .262. He drove in eight runs.

Shortly after his call-up, Lahoud spoke up in appreciation of player agents, a relatively new phenomenon in baseball at the time and agents were far from being generally accepted or approved. Representing Lahoud was Joe Garagiola, Jr. Lahoud said the Rangers had held onto him long enough that spring that several other clubs had lost interest, and alleged that they had put out the word he had a bad back or bad arm. When he was released, he said the Rangers initially tried to withhold $1,600 in expense money due him. Garagiola threatened a lawsuit and got him the money.43

In 1977, the Royals (102-60) finished first in the AL West, a full eight games ahead of the second-place Texas Rangers. They played a best-of-five American League Championship Series against the New York Yankees, and Lahoud experienced his only taste of postseason play. His own participation was brief. The Royals won Game One and the Yankees won Game Two. In Game Three, Lahoud got the start as DH against the Yankees’ Mike Torrez. He drew a walk in the bottom of the second, and came around to score the first run of the game on two successive singles. The Royals scored once more in the third. With George Brett on third base and two outs, Lahoud lined out to the first baseman. He led off the bottom of the sixth and drew another walk, later scoring. When it was his turn to bat in the seventh, the Royals already had a 6-1 lead. With a man on second and two outs, John Wathan pinch-hit for him. Wathan struck out. The Royals won the game, but lost Games Four and Five and it was the Yankees who advanced to the World Series. In three plate appearances, Lahoud had two runs scored and a .667 on-base percentage.

He was offered a contract for 1978 and made the team in spring training. In April and May he served as an occasional pinch-hitter, starting only one game as the DH. He didn’t draw even one base on balls, and failed to get more than one single in his first 15 times up. He pinch-hit and singled to right field in the top of the ninth inning on May 24 in Seattle. Removed for a pinch-runner, by getting himself on first base, the pinch-runner scored the winning run in a 6-5 game. It was his last appearance in professional baseball. On June 1, he was designated for assignment by the Royals. The next day, the Royals asked for waivers to give him his unconditional release.

Joe Lahoud had played parts of 11 seasons in the big leagues, and compiled a .223 career batting average but with a .334 on-base percentage. His career fielding percentage was .979.

“I’m happy that I had the opportunity,” he said. He only regrets that he didn’t have the opportunity to play more, noting that the years he played most often were the years he produced more, particularly 1970 with Louisville and 1974 with the California Angels.

Three years after leaving the game, Lahoud was working for a tax credit consulting firm on Madison Avenue in New York City. During the player strike of 1981, he spoke up saying the owners had gotten themselves into this difficulty, but also suggested that the players might have tried harder to work with the owners, perhaps using a different negotiator than Marvin Miller.44

At first, he’d become a field agent primarily selling life insurance for Northwestern Mutual. “But you only have so many cousins and friends,” he said. “I did that for a year or two and then I opened up a real estate office.” After a while he sold his client base, and started looking around for something he really wanted to do. Reading the Wall Street Journal, he learned about tax credit programs, incentives to companies to hire people who were underemployed. He spent a couple of days researching the relevant laws in Washington DC and then sought out a company that was doing that sort of work — PCS Reports, out of New York. They hired him.

After a period of time, he started his own company, PKH – Pearce, Kennedy, Hearth. “In 1991, we grew the company to the point we were the 51st fastest growing company in the Inc 500 of Inc 500 magazine. The problem with that program was that every year it would have to come up for renewal and sometimes it would go into hiatus for a year or two. Carrying as many as 300 employees, and being at the vagaries of the “on-again, off-again” legislative authorization, he sold the company – more or less just in time before the increased use of computers would have undercut the business model. Lahoud took a position, first as a consultant and then as an employee with Pitney-Bowes, convincing companies to outsource their mailrooms and copy centers and other business functions. After four years (1997-2001), and some work with a couple of smaller companies, by 2003 or 2004, he was working with DTI (now DTI Epiq, the “new global leader in legal services and technology.” It was a $40 million company when he started with them, but a $1.3 billion company when he left in 2017. He says, “I’m not patting myself on the back, but I did very well for them. I brought in well over $150 million in revenues.”

When DTI acquired the Merrill Corporation’s Legal Solutions business, they brought in new people from Merrill and Lahoud was reporting to other executives. They parted ways in 2017.

“Now I’m with a company called CDS – Complete Discovery Source,” Lahoud said in early 2018. “This is all geared toward litigation support for litigators and law firms, general counsels in corporations. It’s geared to electronic discovery for law firms. Anything a law firm needs to support them in litigation. My territory was the Northeast and Northern New Jersey. I grew Boston to eight or nine accounts from nothing. New York and Northern New Jersey was the biggest growth area where DTI had one account; over the years of my tenure it grew to be the number one region in the country.”

Naturally, a number of the executives he calls on – Executive Directors, CIOs, CFOs, CEOs, COOs – recognize his name from baseball. Lahoud often has to remind them he’s there for business. “It was an advantage sometimes and it was a disadvantage sometimes.” But overall, it has probably helped. Life is a challenge; it’s whether you meet it or not.

In February 2018, Joe Lahoud celebrated his 40th wedding anniversary with Patricia Kennedy Lahoud. They have two sons, Joseph III, age 35 at the time, and Nicholas, 31. Nick worked for a year or two in premium sales for the Boston Red Sox. Joe and Patricia live in Woodbury, Connecticut, maybe a half-hour from Danbury.

Lahoud keeps in touch with a number of ballplayers. He came to Fenway Park for the 100th anniversary in 2012, and was honored when Carl Yastrzemski invited him to the unveiling of his statue outside the ballpark in 2013. “I try to play in as many of those Jimmy Fund tournaments as I can,” he said. “And Major League Baseball Alumni runs an enormous amount of programs, and I play in as many as I can. The charities are really good charities. I do a lot with Major League Baseball Alumni, in regards to these clinics that they run. I just love working with the kids.”

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Lahoud’s player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Author interview with Joe Lahoud, February 8, 2018. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations come from this interview. Amusingly, Lahoud received a number of letters from French Canadian fans who followed the Red Sox. “Very flattering,” Lahoud said, chuckling, “The only trouble is I’m of Lebanese descent.” Bill Liston, “Howard Still Upset by Hitting Trouble,” Boston Herald, March 31, 1968: 67.

2 Jack McCarthy, “Lahoud H.R. King of Danbury,” Boston Herald, April 14, 1968: 57.

3 Being signed by Nekola gave him a connection to Yastrzemski. “I think that’s why Yaz and I had a mutual relationship, because we had something in common when I first met him. We talked a lot. He was a good mentor for me.”

4 Clif Keane, “Lahoud – His Swing Is Talk of the Spring,” Boston Globe, April 7, 1968: E43. In the February 2018 interview, Lahoud said, “Don’t cut me short. It was $3,500 and a case of Coca-Cola.”

5 John Gillooly, “Maxvill Stills Feels Desmond Destiny,” Boston Record American, March 20, 1968: 14.

6 Larry Claflin, “Sox Rookie 430-Ft. Homer,” Boston Record American, March 10, 1968: 99.

7 John Gillooly, “Peter Up in the Air, Joe Down in the Dumps,” Boston Record American, May 3, 1968: 60.

8 Larry Claflin, “Sox Lose in 10th, 6-5,” Boston Record American, March 12, 1968: 20.

9 Fred Ciampa, “Heavy Hitting By Lahoud Nice Williams Problem,” Boston Record American, March 12, 1968: 18.

10 Larry Claflin, “Rookie Lahoud Jumps Ahead of Hub’s Timetable,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1968: 13.

11 Harold Kaese, “Tigers Asked, ‘Joe La-Ho?’,” Boston Globe, April 11, 1968: 49.

12 Ibid.

13 Harold Kaese, “Bunt Wouldn’t Assure Victory,” Boston Globe, April 12, 1968: 25.

14 Harold Kaese, “Sad Lahoud Holds Tongue,” Boston Globe, May 1, 1968: 55. Both Yaz and Pop were quoted in the same article.

15 Will McDonough, “Lahoud Angry, Leaving Again,” Boston Globe, July 2, 1968: 46. Just a few years later, Lahoud said in 1971, “What I really needed was more time in the minors.” Phil Elderkin, “Hold for Arrival,” Christian Science Monitor, June 30, 1971: 10.

16 Larry Claflin, “Red Sox Gushing Over Billy C and Joe Lahoud,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1969: 9.

17 Phil Elderkin, “Young Ballplayer in a Hurry Battles Impatience,” Christian Science Monitor, August 11, 1969: B7.

18 Lahoud credited Bobby Doerr with teaching him patience at the plate. “Bob got me thinking and calmed me down. I was always too anxious with the bat.” The 1969 Elderkin article offers more on Doerr’s influence. In another article, he confessed, “I used to be so nervous my left leg would shake in the batter’s box,” Frank Birmingham, “Frankly Speaking, Connecticut Sunday Herald, July 11, 1971: 18.

19 Paul Hart, “’Make or Break’ Year for Joe Lahoud,” Danbury News-Times, February 16,1970: 25.

20 Gerry Finn, “When Agents Help,” Springfield Union, August 18,1977: 8.

21 Laura White, “Joe Lahoud,” Boston Herald, September 19, 1969: 31.

22 Paul Hart.

23 Ron Coons, “Lahoud Rapping Ball, Not Boston, In Full-Time Role,” The Sporting News, May 30, 1970: 47.

24 Lahoud talked at some length with Lahoud, offering very colorful detail on various members of the Red Sox teams on which Lahoud played. Peter Golenbock, Red Sox Nation (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2005), 340.

25 Jack Clary, “Lahoud Sent Down Again, Hopes Sox Will Trade Him,” Boston Herald, April 1, 1970: 31.

26 Ibid.

27 Clif Keane, “Lahoud Sings A New and Different Tune,” Boston Globe, February 19, 1970: 54.

28 For just a taste of the dispute see Associated Press, “Conigliaro’s Brother Raps Yastrzemski,” Washington Post, July 11, 1971: C2. “Smith Says ‘Club Should Discipline Billy Conigliaro’,” New York Times, July 12, 1971: 36.

29 Larry Whiteside, “Lahoud Eager to Start as Brewer,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1972: 44.

30 Wayne Shepperd, “Joe Keeps Sense of Humor Despite Bad Start,” Danbury News-Times, May 17, 1973.

31 Lou Chapman, “No Flag, But Brewers Gained Respect in 1973,” The Sporting News, September 15, 1973: 14.

32 Dick Miller, “Gritty Lahoud: Angels’ Happy Hitter,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1974: 9.

33 “Insiders Say,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1975: 4.

34 UPI, “Kuhn Revokes Sales; Finley Promises Suit,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, June 19, 1976: 17.

35 Ibid., 18.

36 Dick Williams and Bill Plaschke, No More Mr. Nice Guy (San Diego and New York: Harcourt Brace, 1990), 196.

37 Ibid., 176.

38 Randy Galloway, “Extra Innings,” Dallas Evening News, March 1, 1977: 2.

39 “Extra Innings,” Dallas Evening News, March 15, 1977: 3.

40 Howard Brantz, “Lahoud More Than Hitter,” Omaha World-Herald, July 16, 1977: 15.

41 In the February 2018 interview, Lahoud expanded a bit: “Ted was great. When they invited me down to Florida for the instructional league, Bobby Doerr was the coach. We were taking our wings in the cage, then we’d have to run the bases – get to first and take your lead — and then go out in the field. Fundamentals. I came running back in and I hear this voice going, ‘Hey, Bush! You look pretty eff-ing good.’ I turned around and I didn’t know who the hell it was. So I asked Bobby, ‘Bobby, who’s that guy cursing at me over there?’ He started laughing, ‘You don’t know who that is?’ And I go, ‘No.’ ‘That’s Ted Williams.’ I go, ‘Oh my god.’ I almost fell to my knees.

“Bobby said, ‘He wants to talk to you,’ So I went over and he said, ‘You know, Kid. I like the way…blah blah blah. I like the way you swing. I want you to come out here at 7 o’clock in the morning and we’re going to work on your swing.’ So I was out there at 7 o’clock the next morning.

“I used to be a spray hitter. I hit the ball to all fields. Well, he made me a dead pull hitter. It was probably not the best thing for me, but you didn’t argue with him.

“I used to have a hitch. When I started my swing, I’d drop my hands and I’d go to the ball. He didn’t like that. He said, ‘With your power, I want you pulling the ball.’ So what he did – he stood on a stepladder behind me and put a rope through the net in the batting cage, and every time I went to hitch – push down – he’d pull up. He got rid of my hitch. Sure enough, I became a dead pull hitter.

“So I went from a .300-hitter plus my entire life to a .235 hitter (laughs).”

But he lasted. “Yeah, that was the bad news. The good news was that I got to where I could hit the ball out of the ballpark and that kept me around for a while.”

42 Jay Ewolt, “Lahoud Plays Big In Win,” Omaha World-Herald, June 29, 1977: 51.

43 Gerry Finn, “When Agents Help.”

44 Bob Reigeluth, “Joe Lahoud Sides With Striking Players,” Danbury News-Times, July 6,1981: 25.

Full Name

Joseph Michael Lahoud

Born

April 14, 1947 at Danbury, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.