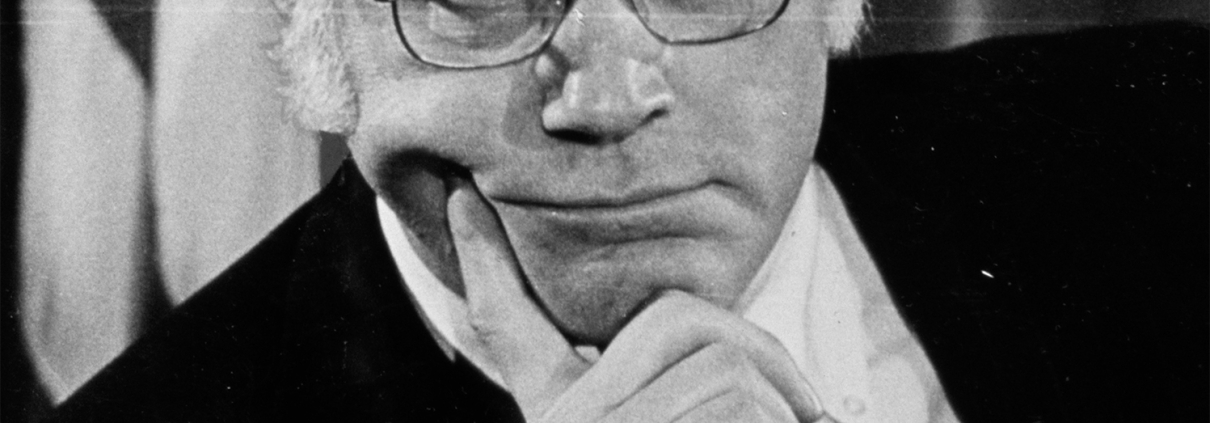

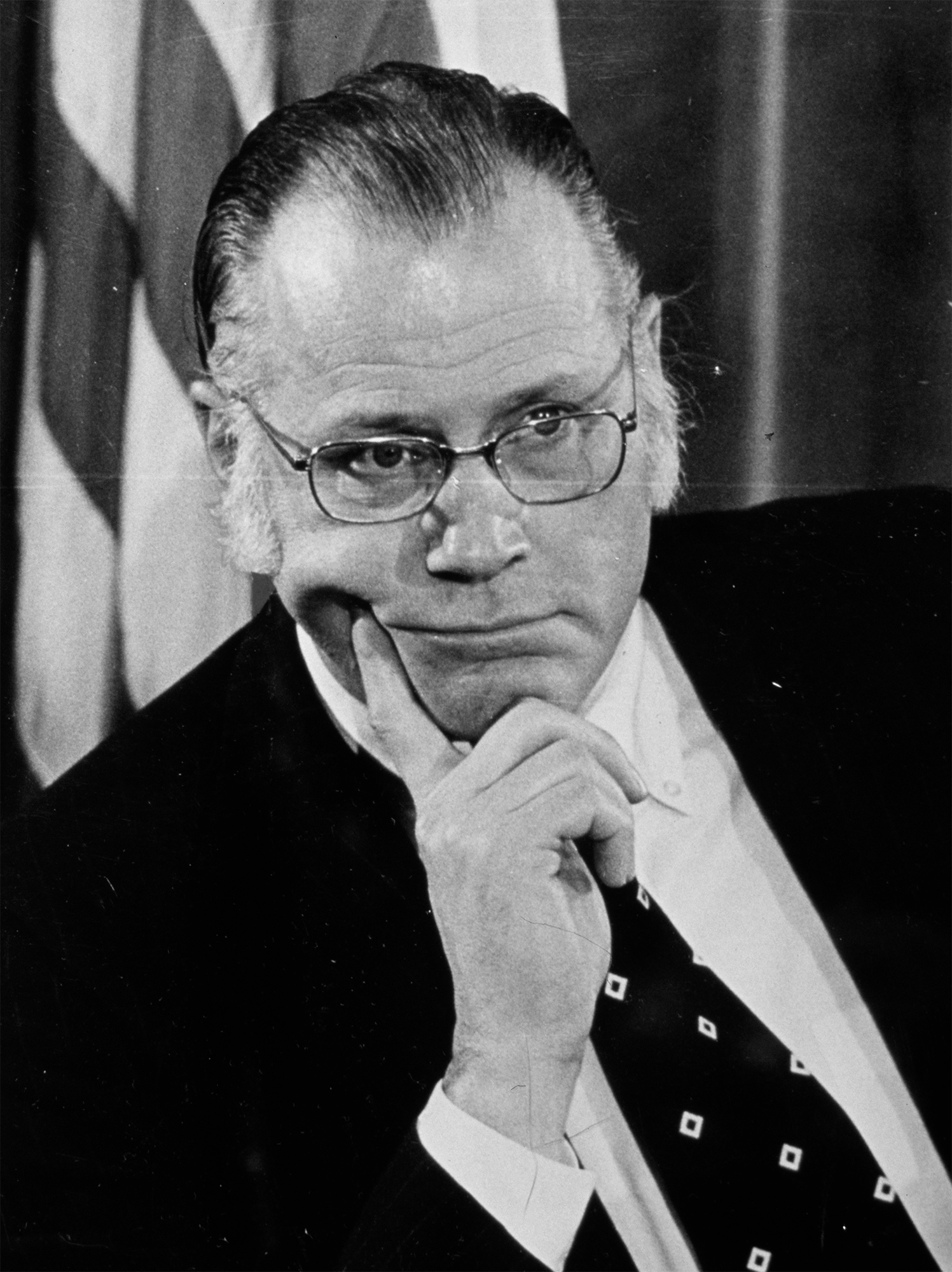

Bowie Kuhn

When Bowie Kuhn was named the fifth Commissioner of Baseball in early 1969, he was touted by owners as the man needed to modernize and strengthen the game of baseball, which was declining in popularity as pro football’s increased. It was a time, Daniel Okrent noted, when professional baseball was fighting for survival.1

When Bowie Kuhn was named the fifth Commissioner of Baseball in early 1969, he was touted by owners as the man needed to modernize and strengthen the game of baseball, which was declining in popularity as pro football’s increased. It was a time, Daniel Okrent noted, when professional baseball was fighting for survival.1

Kuhn, a lawyer who had worked for the firm serving the National League, spent 15 years as the sport’s chief executive, presiding over a period of change unparalleled in the game’s history. He was voted into office unanimously by 24 owners — including four from expansion teams that would take the field for the first time that year. By the time he was forced out by owners in 1984, there were 26 major-league teams. A host of new stadiums had opened — many with new artificial turf. World Series games were played on weeknights (a change for which Kuhn had advocated forcefully; NBC objected — until the overnight numbers came in). A designated hitter had been introduced into the American League. Free agency — and a stronger players’ union — had come to the major leagues, with five work stoppages during Kuhn’s reign.

But Kuhn was a man out of step with the times. A serious, if not pompous man — “Even his undershirt was stuffed,” wrote Dave Anderson of the New York Times2 — Kuhn had grown up an unabashed baseball fan, working as a scoreboard operator (a job that was unnecessary in most ballparks by the time he became commissioner) for the Washington Senators. (It was on his watch that baseball left the nation’s capital, not to return for three decades.) He tried to root out any vestige of gambling in the game, which seems nearly quaint two decades into the 21st century. The sportsmen he admired as owners — men like Horace Stoneham, Joan Payson (obviously, not a man, but possessing those same inherent qualities, he said in his autobiography) and Tom Yawkey — were fading away. They were replaced by a new guard, men like Charles Finley, who referred to Kuhn as “the village idiot,”3 and George Steinbrenner, whom Kuhn suspended for campaign finance violations, and who ultimately led the charge for Kuhn’s ouster. The new breed of owner might have raised Kuhn’s ire more than did Major League Baseball Players Association director Marvin Miller, who served as the commissioner’s foil on more than one occasion.4

Kuhn backed the idea of the DH as well as interleague play, had the foresight to advocate revenue sharing — a potent topic even today — and talked about three divisions and a wild card team well before it was implemented by his protégé, Bud Selig. But in many ways, Kuhn was very much a man standing athwart history, yelling stop. He was a firm believer that the major points of the game should be unchanged. He advocated for the game’s reserve clause during the arbitration hearings for Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, and upheld the ban on female writers in baseball locker rooms. But like Hyman Roth in The Godfather, Part II, Kuhn made money for the game.5 By the time he departed, attendance was higher, television contracts were fatter, and franchise values had increased dramatically.

Okrent saw the commissionership as a “doomed monarchy,”6 and in many ways, Kuhn was part of the slide. At least theoretically, Kenesaw Mountain Landis was a czar, advocating on behalf of the game. Kuhn himself enacted the “best interests of the game” clause, most notably in vetoing sales of players by Finley. He also saw himself as commissioner for the fans, owners, and players. But less than a decade after Kuhn’s departure, the commissioner’s role was filled by Selig, himself an owner (“Baseball’s Henry Clay,” said Kuhn, who had known him for decades7).

“What the world saw was a remote, arrogant man, vain and hung up in the trappings of his office,” Okrent wrote in the review of Kuhn’s autobiography. “What the owners got was more formidable.”8

Bowie Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, in Takoma Park, Maryland, and grew up in Washington D.C., the third child of Louis and Alice Kuhn. Louis Kuhn was a German immigrant, arriving in America as a baby in his aunt’s arms on October 1, 1894.9 The elder Kuhn ended up initially in Pittsburgh, but after fighting for the U.S. Army in World War I, he met Alice Waring Roberts. Her family had come to America in 1634, and branches contained many prominent figures (including Jim Bowie, inventor of the eponymous knife and fighter at the Alamo).10 Alice was also a passionate fan of the Washington Senators.

Louis and Alice married on May 20, 1920, and returned to Alice’s native Washington D.C. Son Lou was born a year later, and a daughter, Alice, was born in 1923, followed by Bowie in 1926.

As a teen, Kuhn worked at the Senators’ home field, Griffith Stadium. “I have had only a few jobs in my life, but the best was scoreboard boy at Griffith Stadium,” he recalled in his autobiography.11 Kuhn was a diligent student at Theodore Roosevelt High School in Washington D.C. At 6 feet, 5 inches, he was also the tallest. His senior year, he was approached by the high school basketball coach, a recent George Washington University graduate not much older than his players.

“Son, you’re the tallest boy in the school,” the coach said. “How come you’re not out for the basketball team?”

“Because I’m a lousy player,” Kuhn told him.

“You let me be the judge of that,” said the coach.

After a week of workouts, the coach said, “You were right and I was wrong,” effectively kicking Kuhn off the team. Even then, Red Auerbach could be a keen judge of talent.12

Following graduation from Roosevelt in 1944, Kuhn enrolled in the V-12 program, a partnership between the U.S. Navy and dozens of colleges, where men would take classes at the colleges and become Naval officers. Kuhn started out first at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and then transferred to Princeton University in New Jersey, where he ultimately graduated with an honors degree in economics. Kuhn then went to law school at the University of Virginia, graduating in 1950.

Kuhn spent the summer in Europe, and then returned to the United States, where he took a job with the firm of Willkie, Owen, Farr, Gallagher, and Walton, at the time one of the most venerable and prominent law firms in the United States. Its alumni included U.S. Supreme Court justices Felix Frankfurter and Charles Evans Hughes, and one of its namesakes was Wendell Willkie, who ran for president against Franklin Roosevelt in 1940 and then became one of the president’s trusted associates.

Willkie’s name on the wall was a selling point for Kuhn, who was enthralled as a teen by Willkie’s dark horse candidacy for president. Another selling point? The firm’s clients included the National League. Kuhn took the job and moved to New York.

One of Kuhn’s earliest jobs with Willkie was working on a case that was headed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Earl Toolson, a minor-leaguer in the New York Yankees farm system, had sued rather than accept a minor-league assignment, challenging baseball’s exemption to antitrust laws, ruled in a court decision nearly 30 years earlier.

The Supreme Court upheld the lower courts’ decisions against Toolson. It also upheld the exemption ruling on precedent, saying that any change to the status would have to come from Congress, which was already holding hearings on the matter.13

Otherwise, Kuhn’s law career was nondescript, with more billings related to corporate law than baseball. While in New York, he met Luisa Degener, a widow, in 1955, and married her the following year in Dutchess County. They remained married until his death in 2007. They had a son, Stephen, and daughter, Alix, together. Kuhn was also stepfather to Luisa’s two sons, Paul and George.14

In 1964, the Milwaukee Braves, with their lease at County Stadium expiring in 1965, sought to move to Atlanta. It was a period of great upheaval for the major leagues, with expansion adding four teams and six teams relocating since 1952 — starting with the Braves decamping from Boston for Milwaukee.

Unsurprisingly, the city sued to keep the Braves in Milwaukee, and Kuhn found himself in an awkward position: As the National League’s lawyer, he had to defend the move, but he said, “My heart and my responsibilities were not in the same place. I have always seen franchise movement as an absolute last resort.”15 His career as commissioner would show one glaring exception to that policy.

In his autobiography, Kuhn noted that the move came in Ford Frick’s last year as commissioner, and posited that had it come before then, Frick would have blocked it. But Frick was on his way out, replaced by William Eckert as commissioner in 1965.16 His reign was brief, and at the owners’ meetings in San Francisco in December 1968, Eckert was thrown over the side. Yankees president Michael Burke was touted as a potential candidate, as was San Francisco Giants vice president Chub Feeney, but no consensus could be reached at the winter meetings. John McHale, a compromise candidate, withdrew from consideration.

Thus, Kuhn — already familiar to owners for his work with the National League — was elected unanimously the following February on the first ballot as interim commissioner. He would receive $100,000 for his one-year term — which was a pay cut from his job at Willkie, Farr, and Gallagher.17

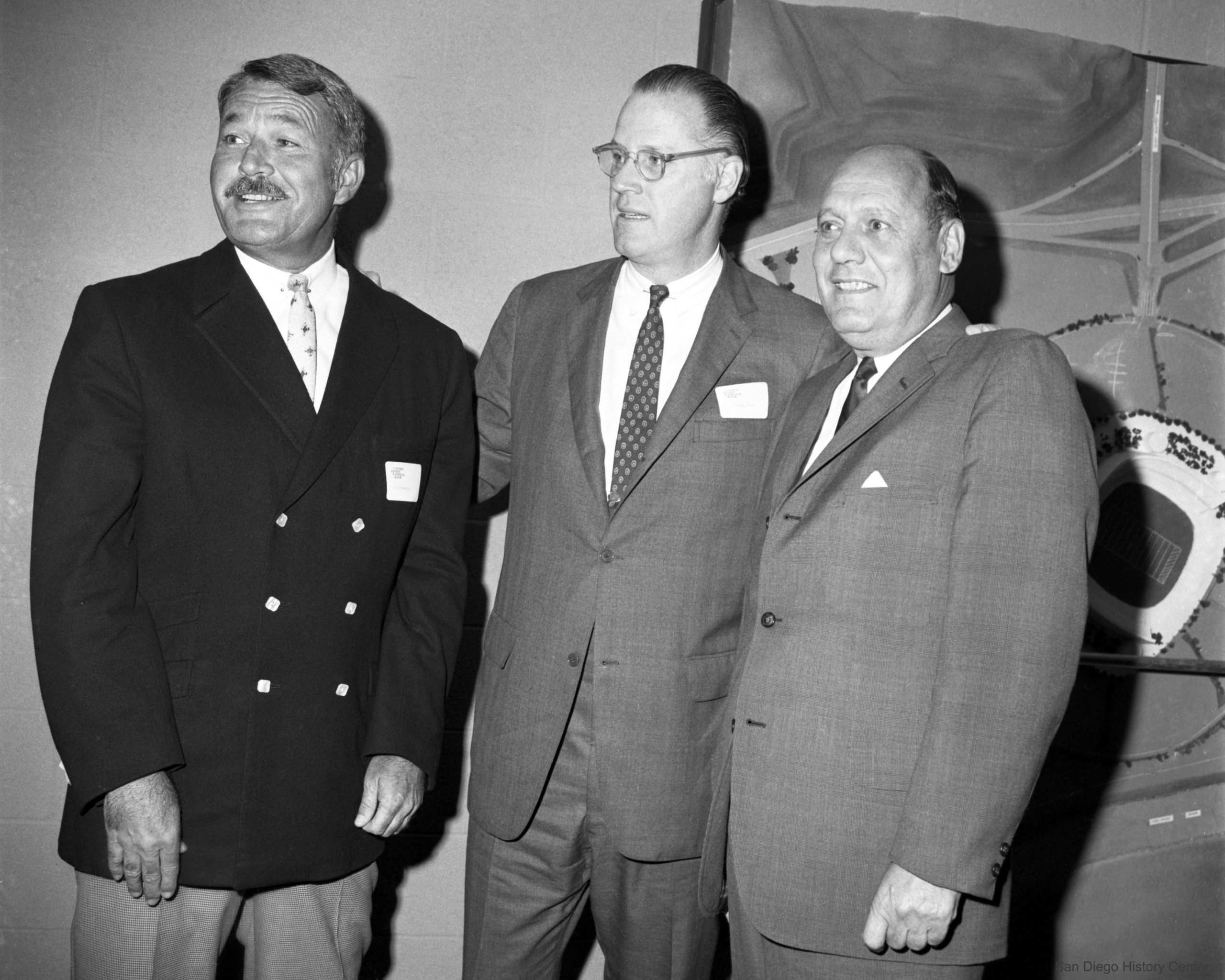

On the eve of the 1969 Opening Day are, left to right, Dr. Albert Anderson, a member of the San Diego Stadium Board of Directors; Bowie Kuhn, Commissioner of Major League Baseball; and San Diego Padres president E. J. “Buzzie” Bavasi. (COURTESY OF TOM LARWIN)

Eckert was an outsider when he was named commissioner. Kuhn was very familiar to owners and league offices. Leonard Koppett of the New York Times noted, “the only similarity (between Eckert and Kuhn) is that most baseball fans never heard of either until they acquired the title of commissioner.”18

Within a month, Kuhn had his first issue to deal with. The Astros had traded Rusty Staub to the expansion team in Montreal for Jesus Alou and Donn Clendenon. The Astros’ manager was Harry Walker, whom Clendenon considered an unrepentant racist. Clendenon opted to retire. Astros owner Judge Roy Hofheinz was beside himself and sought to void the deal. The new Montreal team, the Expos, were already marketing the red-headed Staub as “Le Grand Orange,” and had no urge to send him back to Houston. Kuhn interceded, ordering the Expos to add extra compensation while Clendenon stayed in Montreal (if only briefly; he was traded to the Mets in midseason).

Kuhn also interceded in the Red Sox’ trade of Ken Harrelson to the Indians. The Hawk, no doubt reading the tea leaves of the Clendenon deal, used the threat of retirement to negotiate a new, more lucrative contract. (Harrelson, of course, was already an early beneficiary of free agency, after Finley gave him an outright release from the Athletics.) Kuhn also encouraged bargaining, which had been broken off in the start of 1969, to resume between Miller and the union and the Player Relations Committee, avoiding a potential work stoppage over benefit disputes.19

With the season on time, Kuhn spent his first opening day as commissioner at the newly-renamed Robert F. Kennedy Stadium as Ted Williams made his debut as manager of the Washington Senators. President Richard Nixon was on hand to throw out the first pitch in what was being celebrated as professional baseball’s centennial season. (RFK hosted the All-Star Game that year as well.) Kuhn then went to Jarry Park to watch the first major-league game outside the United States.

The 1969 season ended with Curt Flood being traded from the Cardinals to the Phillies. He was between contracts but, because of baseball’s reserve clause, was effectively bound to the Cardinals. It did not involve Kuhn directly at first, but the trade became the most consequential event in his term as commissioner. On Christmas Eve, Flood wrote a letter to Kuhn saying that the trade violated his rights, and although he had an offer from the Phillies, he wanted to make himself available to other teams.20

“Dear Curt,” opened Kuhn’s reply. A Black man had addressed the commissioner as Mr. Kuhn, and he responded by using the player’s first name, a move the Players Association found patronizing. “I certainly agree with you that you, as a human being, are not a piece of property to be bought and sold. That is I think obvious. However, I cannot see its application to the situation at hand.”21 Flood sat out a year, taking a lawsuit all the way to the Supreme Court. He lost, but the case laid the groundwork for free agency.

In February 1970, Kuhn suspended Denny McLain, in advance of a lengthy Sports Illustrated story detailing the pitcher’s involvement with bookmakers and organized crime figures. (Upon his election, Kuhn said, “The important thing is that Denny McLain and Bob Gibson be household words, not Bowie Kuhn.”22 This was likely not what he had that in mind.)

Kuhn was a hard-liner when it came to gambling in sports, believing the commissioner’s duty was to protect the game’s integrity. The previous year, he had asked Finley and three Braves directors — Bill Bartholomay, John Louis, and Del Coleman — to divest themselves of interests in Parvin-Dohrmann, a company that owned and operated gambling casinos.23 Later on in his tenure, he banned Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays from baseball activities when both had roles working at casinos. But after a year at the helm, owners had taken a liking to Kuhn, and gave him a full seven-year contract that summer.

In 1971, for the second time in little more than a decade, it appeared that the team calling Washington D.C. would relocate. Bob Short, a Minnesota native with no ties to the nation’s capital except involvement in Democratic politics, had bought the Senators following the 1968 season — largely with other people’s money. His own cash flow problems increased, and by 1971, he was teetering on the verge of bankruptcy.24 Kuhn enlisted local businessman Joseph Danzansky to try to buy the team and keep it in Washington, but those efforts failed, and Short ultimately moved the team to Texas.25 Owners voted in favor of the move and Kuhn approved it, noting ruefully in his autobiography that he’d worked at Griffith Stadium and then later served as the Senators’ executioner.

Also in 1971, Kuhn started a panel to help find worthy Negro League candidates for the National Baseball Hall of Fame. At that time, such men were technically proscribed from entering the hall (one of the rules for election by the Baseball Writers Association of America was that players had to play in 10 major-league seasons). It had been five years since Ted Williams’ induction speech urging the recognition of worthy Negro League players, and two years since the BBWAA formed a committee to do so. Opposition was fierce, particularly from former commissioner Ford Frick and the hall’s director. Kuhn announced a worthwhile display of Negro League Hall of Famers in another part of the building — to great outcry. The Hall of Fame, chastened, opened its doors to Negro League inductees, the first being Satchel Paige.26

On October 13, 1971, the first night game was played in World Series history. Game Four was under the lights at Three Rivers Stadium. Kuhn had advocated for weekday games to be played at night (day World Series games on the weekend continued for another 16 years). More than 51,000 fans — the largest crowd to watch baseball in Pittsburgh to that point — were in attendance to see the Pirates beat the Orioles 4-3 — and another 63 million tuned in on television, garnering a 34.8 rating and a 54 share. It was, ironically, one of the few topics on which Kuhn and Finley agreed.27

But any glory for Kuhn was short-lived, as the MLBPA struck for the first time in 1972, over issues relating to pensions and binding arbitration. It was a watershed moment, and Kuhn, by his own admission, was powerless. “This was a matter of collective bargaining, and no commissioner in any sport has the power to say, ‘I am the arbiter, I will settle it,” Kuhn said, adding that he’d worked behind the scenes. He also couldn’t resist taking a shot at Miller, noting, “No other commissioner has had to deal with a professional negotiator and a union. The coming of Marvin Miller as executive director of the players association in 1966 has presented baseball with problems that never existed before.”28 The following year saw a brief lockout before a new agreement was reached, featuring two important changes. The Curt Flood rule was implemented, where a player with 10 years of service, including five with their current team, could veto any trade from that team. Also, binding arbitration was implemented for salary disputes.

When the mound was lowered in 1969 following the year of the pitcher, other ideas, including a designated hitter, were proposed. As the 1970s dawned, the idea of the DH got more traction thanks to owners like Finley, whose profile was rising as the Athletics started winning. Kuhn said because Finley was for it, there were owners, like the Dodgers’ Walter O’Malley, automatically against it. In 1973, the American League agreed to adopt the designated hitter on a three-year trial basis, and after that trial basis, adopted it permanently. The American League also endorsed interleague play. The National League did not. Kuhn, who did support it, could have cast a deciding vote for it, but opted instead for a commission to study the idea.

Hank Aaron ended the 1973 season with 713 home runs, one shy of Babe Ruth’s career record at the time. Prior to the 1974 season, Braves owner Bill Bartholomay announced that Aaron would sit out the opening series of the season in Cincinnati and make his debut in front of the home fans. Kuhn interceded, saying such a move endangered the integrity of major-league baseball, and lobbied Bartholomay to change his mind. (Kuhn said that had no announcement been made and Aaron came down with an injury that kept him out for three days, he likely wouldn’t have acted.29) With Kuhn and Vice President Gerald Ford watching, Aaron hit the record-tying home run in Cincinnati in the season opener.30 The Braves returned to Atlanta, and in their home opener against the Dodgers, Aaron hit the record-breaking home run.

Bowie Kuhn was in Cleveland. He’d addressed the Wahoo Club that day and had sent Monte Irvin to Atlanta in his stead, with the intent to join him at some point. After all, nobody knew when Aaron would break the record, right? Irvin was introduced as a representative of Kuhn … and booed. The incident led to a rift between Kuhn and Aaron for years.

In 1975, Kuhn was elected to a second term as commissioner — not without controversy. Finley tried to engineer a putsch with the aid of Jerry Hoffberger, who had owned the Orioles since their move from St. Louis. The Orioles were never the cash cow Hoffberger had hoped for, and he was shopping the team around. Kuhn, who once invited Hoffberger to dinner and stuck him with the check, a slight for which the Orioles owner never forgave him, wanted to see the team sold to Washington interests.31 Early straw polls indicated that Finley and Hoffberger had enlisted Steinbrenner, still smarting from his suspension for campaign finance violations, and Rangers owner Brad Corbett. Kuhn recalled Mickey Mantle and Billy Martin, well in their cups, knocking on doors and lobbying against Kuhn.32 Ultimately, though, he was re-elected unanimously by National League owners, joined by 10 of the 12 American League owners.33

That December, federal arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled in favor of pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, effectively ending the reserve clause in major-league baseball. The era of free agency was underway, and Finley, realizing that many of his players would leave, started dealing them away. He sold the contract of Vida Blue to the Yankees and those of Rollie Fingers and Joe Rudi to the Red Sox at the trade deadline, netting a total of $3.5 million, but the deal was voided by Kuhn — and more than a few people saw it as retribution by the commissioner against one of his foes. Finley, unsurprisingly, sued, but two years later, by which time the players had all found new homes as free agents and the Athletics were the dregs of the American League West, a federal judge ruled that Kuhn had acted within his powers as commissioner.34

In 1981, the players union struck again, for 50 days, the longest and most acrimonious work stoppage to that point. Unlike in 1972, when Kuhn said he had no authority to interfere, “I could have stopped that strike at any time in ’81, and I decided that the wisest course was for the players to take their licking on this one in the hopes that we wouldn’t face the same problem” in the future.35 At the end of that season, nine owners, smarting from the strike, wrote Kuhn that they wouldn’t support him in a bid for another contract.

Kuhn’s luck finally ran out in 1982, as he sought yet another contract as commissioner. To get it, he needed approval of three-quarters of the owners in each league, and while he got that in the American League (the nays were Steinbrenner, Eddie Chiles of Texas, and George Argyros of Seattle), he was unable to get the votes in the National League. Astros owner John McMullen, Braves owner Ted Turner (whom Kuhn had fined and suspended — later rescinding the suspension — for tampering in trying to sign Gary Matthews), Cardinals owner Gussie Busch, Reds owner William Williams, and Mets owner Nelson Doubleday voted against retaining Kuhn. Except for Busch, the votes against Kuhn were all from members of baseball’s new guard, taking ownership of their teams during Kuhn’s reign as commissioner.36

Kuhn stayed on as commissioner to help find a successor, who turned out to be Peter Ueberroth, Time’s Man of the Year for his efforts organizing the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. In 1987, Kuhn published a book, Hardball: The Education of a Commissioner,37 and even contemplated getting back into baseball — as an owner! He said in an appearance at Hiram College in Northeast Ohio that he considered trying to buy the Cleveland Indians before the Jacobs brothers, Richard and David, did so.38 “I got interested in the Indians when Dave LeFevre’s group stalled,” Kuhn said. “That’s when I thought about putting together a group of friends to buy it. I know we could have gotten the money, but it would have taken more time than I was willing to give.”39

Kuhn returned to Willkie, Farr, where partners described him as a man long on ceremony but short on work. It was expected that he’d probably transition into some kind of foundation role,40 but in 1988, he formed a new law firm with Harvey Myerson, a famed New York trial lawyer whose clients had included Donald Trump in his lawsuit against the NFL.41 In December 1989, Myerson & Kuhn filed for bankruptcy, and the following spring, the New York Times noted that Kuhn was in Florida — but not for spring training. He had sold his home in New Jersey and moved to the Sunshine State, which protected residences from being seized in bankruptcy proceedings. Kuhn was on the hook for at least $3.1 million in debts; Myerson was ultimately convicted of fraud in 1992.42

Kuhn remained in Florida, where he founded a consulting firm, and served as sort of a lay minister for his Catholic faith. In October 2004, he had heart surgery, repairing a valve as well as a double bypass. The following April, when baseball returned to Washington D.C, he was in attendance as Selig’s guest at the new Nationals’ opener against the Diamondbacks at RFK Stadium.43

Kuhn died March 15, 2007, at the age of 80, at St. Luke’s Hospital in Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, where he had been hospitalized for several weeks with pneumonia. Upon Kuhn’s death, Ueberroth said, “Bowie was a great commissioner, and in my opinion he belongs in the Hall of Fame.”44 And that December, Kuhn was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee (as was O’Malley, seen by many of the owners that hated Kuhn as the one pulling the strings). Miller, who also appeared on the ballot, was not. “That’s like putting Wile E. Coyote in the Hall of Fame instead of the Road Runner,” Jim Bouton said.45 It would be a dozen years before that oversight was corrected.46

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Henry Kirn.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the Bowie Kuhn files, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Notes

1 Daniel Okrent, “Baseball’s Ruling Servant,” New York Times, March 8, 1987: 380.

2 Dave Anderson, “Why Bowie Kuhn rose from the dead,” New York Times, July 18, 1975: 48.

3 Kuhn was slightly more diplomatic, saying in his autobiography that Finley “had few redeeming qualities,” not necessarily an uncommon opinion of him. Bowie Kuhn, Hardball: The Education of a Commissioner (New York City: Times Books, 1987), 126.

4 Kuhn was quoted in his New York Times obituary as saying Miller had “the wariness one would find in an abused animal.” Richard Goldstein, “Bowie Kuhn, 80 former baseball commissioner, is dead,” New York Times, March 16, 2007: C10.

5 And, like Roth — spoiler alert — ended up being cast aside, albeit not as violently, in a power consolidation.

6 Okrent, “Baseball’s Ruling Servant.”

7 Kuhn, 412.

8 Okrent, “Baseball’s Ruling Servant.”

9 Kuhn, 14.

10 Kuhn, 12.

11 Kuhn, 15.

12 Kuhn, 14. Kuhn notes that Auerbach, who left to join the Navy, was succeeded by another coach, who talked Kuhn back onto the team, where he lettered as a senior.

13 Those were the hearings where Casey Stengel gave an imitable, incomprehensible statement to House members, which then prompted Mickey Mantle to say, “My views are just about the same as Casey’s.” The case was Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc., 346 U.S. 356 (1953).

14 Richard Goldstein.

15 Kuhn, 21.

16 Before owners agreed on Eckert, Pirates owner John Galbreath suggested as commissioner Paul Brown, in his brief interregnum after being fired by the Browns and before starting the Cincinnati Bengals. https://www.dispatch.com/article/20130929/sports/309299746

17 Leonard Koppett, “Bowie Kuhn, Wall Street Lawyer, Named Commissioner Pro Tem of Baseball,” New York Times, February 5, 1969: 29.

18 Leonard Koppett, “Bowie Kuhn, Ambassador,” New York Times, February 6, 1969: 45.

19 Kuhn, 40.

20 Letter from Curt Flood to Bowie Kuhn, U.S. Archives. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/278312, accessed November 2, 2021.

21 Correspondence between Curt Flood and Bowie Kuhn, Kuhn clip file, Baseball Hall of Fame.

22 Koppett, “Bowie Kuhn, Ambassador.”

23 Among Parvin-Dohrmann’s holdings were the Stardust, which they bought from the remnants of the Cleveland Mayfield Road Gang — and later sold to Allen Glick’s Argent Corporation, a story thinly fictionalized in the movie Casino.

24 That 1971 Senators team included Denny McLain and Curt Flood, prompting Kuhn in his memoirs to say, “Poor Short seemed to be collecting everyone’s problems.”

25 Danzansky was also the man who tried to buy the Padres and relocate them to Washington two years later.

26 Kuhn, 110. He said he made the announcement envisioning exactly what happened, that people would be so upset that they would demand equal induction.

27 Bill Francis, “A Classic Under the Lights.” BaseballHall.org, https://baseballhall.org/discover/a-classic-under-the-lights, accessed November 2, 2021.

28 Carl Lundquist, “Weak or strong? Kuhn’s role aired,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1972: 33. Kuhn clip file, Baseball Hall of Fame. Kuhn’s two living predecessors as commissioner, Ford Frick and Happy Chandler, backed up his claim, both noting that many of the commissioner’s powers had been limited after Judge Landis’ death.

29 Kuhn, 122.

30 And they did boo. They were not saying “Boooooooowie.” The author says, “I will never pass up a chance to make a Simpsons reference.”

31 Peter Richmond, Ballpark: Camden Yards and the Building of An American Dream (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993), 56-57.

32 Kuhn, 150.

33 Joseph Durso. “Owners elect Kuhn as Finley’s coup fails,” New York Times, July 18, 1975: 48.

34 Jerome Holtzman, “Charlie Finley courted disaster, and he got it in baseball’s ‘best interests,’” Chicago Tribune, June 25, 1989. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1989-06-25-8902120504-story.html

35 Murray Chass, “Kuhn’s Legacy Is Not All That It Seems,” New York Times, March 20, 2007: D5. “They won it?” Chass quoted Marvin Miller as saying.

36 Joseph Durso, “Kuhn is voted out as baseball commissioner,” New York Times, November 2, 1982. https://www.nytimes.com/1982/11/02/world/kuhn-is-voted-out-as-baseball-commissioner.html

37 Astros owner John McMullen had sought to block Kuhn from writing any type of baseball-related memoir as a condition of his severance. Kuhn, 435.

38 The college, the alma mater of President James Garfield, was notable for hosting Browns training camp from 1952 to 1974.

39 Paul Hoynes, “Stuffed shirt Kuhn finally loosens up,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 19, 1987: 79.

40 Steven Brill, “How Could Anyone Have Believed Them,” American Lawyer, November 1989, Bowie Kuhn clip file, Baseball Hall of Fame

41 “Myerson guilty of overbilling clients,” United Press International, April 29, 1992. https://www.upi.com/Archives/1992/04/29/Myerson-guilty-of-overbilling-clients/2840704520000/

42 David Margolick, “Bowie Kuhn Is Said to Be in Hiding,” New York Times, February 9, 1990: D1.

43 Associated Press, “Kuhn, 78, upbeat after bypass and more,” ESPN.com, November 2, 2004, https://www.espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=1914765

44 Mike Kupper, “Bowie Kuhn, 80; baseball’s commissioner in stormy era,” Los Angeles Times, March 16, 2007. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2007-mar-16-me-kuhn16-story.html

45 Jorge Arangure Jr., “Miller remembered for his place in the game, and his absence in the Hall,” New York Times, January 22, 2013. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/22/sports/baseball/marvin-miller-remembered-for-his-influence-on-baseball.html?_r=0

46 Marvin Miller was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2020, with ceremonies held on September 12, 2021.

Full Name

Bowie Kent Kuhn

Born

October 28, 1926 at Takoma Park, MD (USA)

Died

March 15, 2007 at Jacksonville, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.