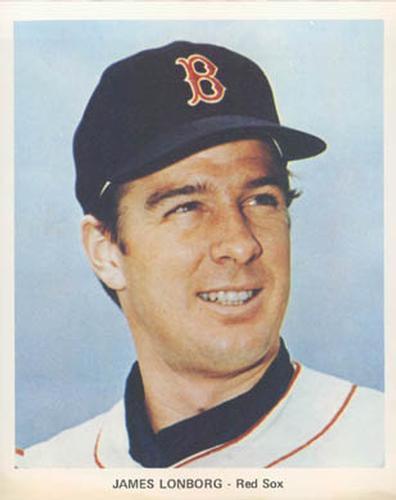

Jim Lonborg

He made his big-league debut on a day when Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. addressed thousands of civil rights marchers on the Boston Common, and flourished as a pitcher during the Summer of Love. As he struggled with injuries, Americans grappled with the strain of assassinations, racial riots, and the escalating Vietnam War.

He made his big-league debut on a day when Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. addressed thousands of civil rights marchers on the Boston Common, and flourished as a pitcher during the Summer of Love. As he struggled with injuries, Americans grappled with the strain of assassinations, racial riots, and the escalating Vietnam War.

Jim Lonborg’s all-too-brief tenure with the Red Sox coincided with some of the most turbulent years of the 20th century, and he was traded just as his full strength was returning and the war was winding down. But the soft-spoken, cerebral hurler will always be remembered — and revered — for what he accomplished during a two-week span in 1967 when New Englanders put other cares on hold and attached their Impossible Dreams to his powerful right arm.

The first Cy Young Award winner in Red Sox history was born on April 16, 1942 in Santa Maria, Calif., and raised in nearby San Luis Obispo. The coastal community was home to the California State Polytechnical College, where Lonborg’s father Reynold worked as a professor of agriculture.

A straight “A” student, Jim dreamed of being a surgeon rather than a World Series star. The Lonborgs were an athletic clan — Reynold was a top hurdler at Fresno State, where Jim’s older brother Eric would later star in football and track — but the family’s primary focus was on academic achievement and good citizenship. While Reynold was teaching or working the fields with his students, his wife Ada took care of Jim, Eric, and their little sister Celia; when Reynold returned home at night, Ada was often off to host a local TV talk show dedicated to current events.

Lonborg was 10 when the town built a Little League and softball field just a block from his house. His first team was the Kiwanis Red Sox, and he participated in the town’s first-ever Little League game. “Those were the days when you’d come home from school, drop off your books, and just go out and play ball all day,” he says. “After the Dodgers moved from Brooklyn to LA, I became a big fan of Don Newcombe and Sandy Koufax, and so I was a pitcher, too.”

Too skinny for the gridiron, Lonborg focused on baseball and basketball at San Luis Obispo High. The right-hander didn’t make the varsity pitching squad as a sophomore, but by his senior year was its ace. Coaches later remembered him as “the hardest-working kid on the field,” but his talent had not yet taken full bloom.

“I was very good at times, but at other times just mediocre,” he recalls. “We had a shortstop, Mel Queen, who was my best friend growing up. He was our star, and signed for something like an $80-90,000 bonus with the Reds out of high school. He married my sister and eventually became a pitcher in the big leagues.”

Scouts were often in the stands at San Luis Obispo games to look at Queen, and made inquiries about Jim when he pitched well. “But they knew I was academically oriented, and I was going to be a pre-med student in college. From what I understood, they were afraid of signing me to a bonus and then having me quit after a couple years.”

Good enough as a 6-foot-5 basketball center to be “quasi-recruited” by Stanford, Jim earned an academic scholarship from the school. He played on the freshmen hoops squad — NCAA rules then barred first-year collegians from varsity teams — but was stuck behind 6-foot-9 future All-American Tom Dose on the depth charts.

Then spring came around, and baseball tryouts. Jim made the freshman team and was on his way. He had a decent season, and, leaving basketball behind, graduated to the varsity pitching staff in ’62. “I had a really good year, and by that summer, the Orioles were starting to take a real strong interest in me.”

Baltimore was in the midst of building an American League powerhouse through its farm system, and funded summer-league teams where promising youngsters could perform under their watch while maintaining their amateur status. Lonborg was assigned to the Everett (Wash.) Orioles of the Northeast League, where he suited up for five to six games a week and lived with a host family.

“That was my first summer living away from home, and it was a great experience,” he remembers. “I was young and strong and had a rubber arm. In a playoff doubleheader against Bellingham I won the first game, told the manager I felt good, and wound up pitching the second one too — 18 innings in one day.”

After an MVP junior season at Stanford — where he was majoring in Biology — Jim was invited by the Orioles to join the highly competitive Basin League in the summer of 1963. Playing in rural South Dakota on a team with future big leaguers Jim Palmer and Merv Rettemund, Lonborg stood out. Baltimore scout Phil Galvin was overseeing his progress, but scouts from other major league clubs often made the trip to the woods as well.

“I was throwing an awful lot, two games a week plus between starts, and one day Red Sox scout Danny Doyle recommended to the manager that they rest me up a little more. We tried it out, and the next start I struck out something like 17 guys. Bobby Doerr was in the stands that night for Boston, and that’s when the Red Sox started to make a strong move.”

These were the days before the annual major league draft. Although he felt a strong allegiance to the Orioles, Lonborg wound up signing with the Red Sox for a much higher bonus offer of $25,000 at summer’s end. “The Orioles couldn’t believe it, but I guess the Sox had had a good year financially, and Tom Yawkey told his scouts to go out and get some guys. It was a hard decision for me, but one that amounted to economics.”

After two more quarters at Stanford (where he would later complete his degree in the off-season), Lonborg reported to Deland, Fla. for spring training with the Triple A Seattle Rainiers. He split the year between Seattle and Single A Winston Salem, and was a combined 11-9. The next spring he was invited to Boston’s big-league camp.

The perennial second-division Sox were desperate for pitching help in 1965, and the 22-year-old was given a strong chance to make manager Billy Herman‘s club. Almost immediately, reporters began playing up his background. While in college Jim had developed a taste for symphony music, and this became a frequent reference point for sportswriters. “I remember at Stanford in a fine arts course, we were studying the Brandenburg Concertos,” he told the Boston Globe. “There was a bunch of us, guys and coeds, listening to it at the Phi Delta Theta house. And this Bach thing really got to us. We started dancing to it, twisting.”

The image seemed to capture the handsome young bachelor — a perfect meld of culture and cool. He was capable of taking the short stroll from Fenway Park to Symphony Hall one night, then hitting the rock-oriented nightclubs of Kenmore Square the next. He also had pitching sense and confidence well beyond his years, and in a surprising move to start the season, Herman named Lonborg as one of his four starters along with ace Bill Monbouquette, Earl Wilson, and Dave Morehead.

With a then-familiar Boston blend of strong hitting, thin pitching, and suspect defense, the Red Sox were a consensus pick to place ninth in the 10-team American League. After six straight losing campaigns, fans of the club were looking for reasons to hope. The lanky right-hander with the high leg-kick provided one immediately.

In his big-league debut at Baltimore on April 23, Jim let up just two hits over six innings, while notching four strikeouts. He did allow five walks and three runs while taking the loss against Hall of Famer Robin Roberts, but it was a strong first impression. Back in New England the big news was Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech on Boston Common promoting racial harmony, but buried in the sports pages of the Globe was a prophetic opening line from Roger Birtwell’s account of the Orioles’ 4-2 victory: “The Red Sox Friday night lost a ball game, but found a pitcher.”

More strong starts followed, including a pair against the defending AL champion Yankees for his first two major league victories. Jim today credits veterans like his locker-room neighbor Wilson for providing the pitching wisdom necessary to survive in the majors, and Herman for assuring him he had the stuff to do so. The manager was right; Lonborg possessed an explosive fastball, along with a strong breaking ball he could throw for strikes and which hitters often sent into the dirt. Unfortunately, a ground-ball hurler and irregular defense didn’t always mix, and the end result was a 9-17 record and 4.47 ERA for the Sox, who met expectations with a ninth-place finish.

Asked if all the “Dr. Lonborg” and “Stanford slinger” stories that first year got to him, he laughs. “Sure, there was a lot of ribbing because of it, but you learn how to have very thick skin. And if you’re healthy and pitching well, a lot of that stuff falls off. My parents instilled strong self-esteem in me. It would have taken a lot for me to break.”

With the Red Sox coming together as a team in 1966, Jim’s pitching record improved. Shortstop Rico Petrocelli and first baseman George Scott, young players with great gloves, were now gobbling up his grounders, and Lonborg was a solid 10-10 with a 3.86 ERA for the season. Hoping they had the makings of a big winner, Boston management sent him to work on his breaking ball in the Venezuela winter league. After play there ended around Christmas, he went back to California and one of his off-season passions: skiing.

“The team didn’t even know I skied then. It was just something I liked to do, and I figured that there couldn’t be anything better for your leg and shoulder strength and your overall conditioning. I left Heavenly Valley [resort] on a Friday morning, and I was in spring training on Saturday in the best shape of my life.”

Awaiting the Red Sox in Winter Haven was new manager Dick Williams, a stern disciplinarian who had managed many of the team’s young players at Triple A Toronto. “Dick came in with very strong ideas about the way things should be done,” says Lonborg. “He knew he had some great athletes, but a lot of them were doing their own thing. He really helped everybody congeal with his personality. If you made mistakes, he’d let you know about it. If you continued to make them, he really let you know about it.”

Williams was out to alter the “country club” image of the team, and Jim welcomed the change. No pitcher looked better in camp, and Lonborg made headlines when he stated his goals were to win 20 games, make the All-Star team, and pitch in the World Series. While few imagined all three could happen that year, big things were expected of the man tabbed by Williams as the team’s No. 1 starter.

And after frigid, windy weather forced a one-day postponement of the team’s home opener, Lonborg got the season off to a good start. On Wednesday, April 12, he hurled 6-plus strong innings in a 5-4 victory over the Chicago White Sox. Just 8,324 fans turned out at Fenway Park that bitterly cold day, but sparse home crowds in any weather would soon be a thing of the past.

With Jim compiling a 6-1 record during the first two months, the surprising Sox ended May in third place. Emerging as a certified power pitcher, he had a 13-strikeout, zero-walk shutout against the A’s in one April game and 71 strikeouts overall in his first 70 innings. Forced several times to leave the team between starts for Army Reserve duty, he would fly in on a private plane sent by Tom Yawkey in time to pitch another gem.

By early summer, the American League pennant race was shaping up to be a four- or even five-team affair, and just as Carl Yastrzemski guided the offense, Lonborg set the tone for the mound corps.

Jim’s low-key, friendly demeanor in past seasons had earned him the nickname “Gentleman Jim,” but with the help of Red Sox pitching coach Sal Maglie, he was asserting himself more on the mound by throwing high-and-tight fastballs to keep hitters on edge. His 19 hit batsmen would lead the AL in ’67, but many were in “retaliation” for a plunked teammate. And even in these situations, he always seemed to keep his cool.

The evening of June 21 at Yankee Stadium provides an example. Sox third baseman Joe Foy had hit a grand slam the previous night, so New York starter Thad Tillotson beaned him on the helmet in the second inning. Lonborg responded by hitting Tillotson when he came up, and a five-minute, bench-clearing brawl ensued. Tillotson next sent Jim sprawling with a pitch in the fourth, leading to more heated words and shoving between the teams. But while the melee rattled Tillotson, who was removed in the fourth, Jim pitched a complete-game victory and allowed just one unearned run.

Named an AL All-Star, Lonborg was 11-3 and leading the AL in victories by early July. Just before the break, he pitched one of the forgotten gems of the season — a 3-0 win in which he lost 12 pounds over seven stellar innings on a hot, muggy day in Detroit. The win halted a stretch of five straight losses by the team and was soon followed by a 10-game winning streak.

From late July on Boston would never be more than 3 1/2 games out of first place, and usually much closer. Knowing his youthful team was still considered the underdog in a race against veteran clubs like the Twins and Tigers, Sox general manager Dick O’Connell made a key move on Aug. 3 by acquiring Yankees catcher Elston Howard. A former MVP and a veteran of nine World Series, Howard had a huge influence on his new team — especially its ace pitcher. “Mike Ryan and Russ Gibson were great young catchers,” Lonborg says, “but when Elston got there, he took a lot of pressure off of me in trying to figure out the best way to get hitters out.”

When Lonborg earned his 20th win over Catfish Hunter and the A’s on September 12, it put the Red Sox in a tie for first place. A usually weak hitter, Jim aided his own cause with an eighth inning triple that plated the winning run, and moments later scored an insurance run on a sacrifice fly. Two of his pre-season goals had now been accomplished. The biggest remained.

Dick Williams had his pitching rotation set so Lonborg could start twice during the last week of the year, including (if necessary) in the season finale. When Jim was hit hard in a loss at Cleveland on Wednesday, Sept. 27, the Sox fell a game behind first-place Minnesota. But fate and the schedule had the Twins in at Fenway for the last two games of the season, and after a 6-4 win by the Sox on Saturday the teams were tied again at the top. Sunday’s winner-take-all affair would feature a duel of aces: Dean Chance (20-13) against Lonborg (21-9), who was 0-3 that year and 0-6 lifetime against Minnesota. A few months earlier, Chance had beaten Lonnie with a no-hitter halted by rain after five innings.

Jim pitched better on the road throughout the 1967 season, but this wasn’t the only reason he decided to stay in teammate Ken Harrelson‘s hotel room the night before the biggest ballgame of his life. “I was living at Charles River Park, a very active complex,” Lonborg explains. “There was a lot of traffic going in and out, and I really needed a quiet place to get ready for the game. I stayed at the Sheraton right near the Hynes Auditorium, had a nice dinner and some wine, slept well, and woke up a lot more relaxed than I would have had I stayed at home.”

Although he was later quoted as saying, “I just knew I was going to win,” Lonborg gave himself added incentive before the contest by writing the figure “$10,000” — what he estimated to be each player’s World Series share were the Sox to make it — into the palm of his glove. When uncharacteristic defensive miscues by Gold Glove teammates Yastrzemski and Scott led to two unearned runs and a 2-0 Twins lead entering the bottom of the sixth, Jim grew concerned. But then came what might have been the biggest of Boston’s 1,394 regular-season hits, from the unlikeliest source in the lineup.

“For some reason I always hit Chance very well,” says Lonborg. “He was having a great year, but I just seemed to pick up his ball well and had gotten a single my first time at-bat that day. Going up to the plate in the bottom of the sixth, I looked down to third base for a ‘take’ sign from coach Eddie Popowski, and he didn’t give it. I had bunted a lot during the course of the year, and could run pretty well for a big guy. Cesar Tovar seemed back a little further at third base than normal, and I had an opportunity on the first pitch to lay one down. Tovar couldn’t handle it, and that just started things off.”

Given his blue warm-up jacket at first base, Lonborg quickly came around to score as the next three batters — Jerry Adair, Dalton Jones, and Yastrzemski — all followed with first-pitch singles. A few botched grounders and wild pitches later, and Boston had the crowd on its feet and a 5-2 lead going into the seventh.

Minnesota got one run back in the eighth, but lost a chance for more when Yaz deftly handled Bob Allison‘s liner to the left-field corner and threw him out at second base. It was still 5-3 with two outs and one on in the Twins ninth when pinch-hitter Rich Rollins hit the first pitch he saw from Lonnie high into the air behind shortstop. Rico Petrocelli grabbed it, and Red Sox broadcaster Ned Martin perfectly summed up what happened next when he told listeners: “…and it’s pandemonium on the field!”

As Jim leaped up and down, Andrews and Scott came over and lifted him onto their shoulders. Other players from the field and dugout quickly swarmed around them, as did many of the 35,770 fans on hand who for the first time in decades had a reason to jump the low walls separating them from their heroes. One photograph shows a beaming Lonborg literally riding above a sea of revelers, many of who are reaching out to touch him and “grab” a souvenir.

Then, as he recalls, “the crowd starting moving toward the right-field foul pole, and I was trying to get back to the dugout. A lot of articles of my clothing were starting to disappear; the moment of jubilation had passed, and now the moment of anxiety had started to set in.” By the time he reached the dugout, Jim had lost the buttons on his uniform jersey, the undershirt beneath it, a shoelace, and his cap.

Now assured of a tie for the AL pennant, the Sox claimed the flag outright a few hours later when second-place Detroit lost the second game of a doubleheader to California. Owner Tom Yawkey, in an unusual public display of emotion, gave his champagne-soaked ace a bear hug and broke down while telling Lonborg how terrific he had been. The numbers bear Yawkey out: Jim finished the regular season 22-9 and led the league in wins, strikeouts (246), and starts (39) while placing second in complete games (15) and innings (273.1).

As Bostonians partied hard into the night, high school senior Rosemary Feeney struggled to get some sleep. In town with her mother to visit Garland Junior College, she was staying across the street at the Hotel Somerset. Both establishments were around the corner from Fenway Park, but despite the noise Rosemary wound up going to school at Garland. Lonborg met the New Jersey native at a party in Boston three years later, and they married in November 1970. Six kids and several grandkids later, they are still going strong.

The thrilling finish left Jim unavailable to start Game One of the World Series against heavily favored St. Louis at Fenway three days later. After the Cardinals and their ace pitcher Bob Gibson had taken the opener, 2-1, Lonnie was near perfect in evening up the series.

Facing a lineup featuring Hall of Famers Lou Brock, Orlando Cepeda, and several other All-Stars, he set down the first 19 men in order before walking Curt Flood in the seventh. The Cards had no hits until Julian Javier‘s double with two outs in the eighth, and they did not get another as the Red Sox evened the Series with a 5-0 win. Yaz had two homers and four RBI, but Jim’s one-hitter was the big story. In from California, Lonborg’s mom and dad watched on proudly.

Boston’s other starters could not maintain Jim’s momentum, however, and St. Louis won the next two games (including a Gibson shutout) to put the Sox on the brink of elimination. Then, starting his third crucial contest in eight days, Lonborg in Game Five nearly matched his previous masterpiece. Pitching a three-hitter, he had a shutout until Roger Maris homered with two outs in the ninth inning of a 3-1 Sox victory at Busch Stadium. Through 18 innings, Lonnie had now allowed four hits and one walk, the greatest back-to-back pitching performances in World Series history.

Jim credits “great physical stuff and great emotional concentration in those two games” as the key, along with some advice he got from his boyhood idol, Sandy Koufax. “Sandy was one of the TV announcers for the Series, and we had a wonderful conversation about preparing for a game in the bullpen — visualizing which hitters were coming up to the plate and almost pitching a game in your mind before you’ve even walked out on the field. That was very, very helpful.”

In athletics, however, optimism and talent can sometimes be trumped by physical exhaustion. This is what happened after the Sox won Game Six and Jim started the finale at Fenway on just two days rest against Gibson — who had enjoyed his normal three-day break after Game Four.

Lonborg remembers feeling strong and comfortable before the game, but Sox coach Bobby Doerr noticed early that his pitches lacked the “snap” of his previous three starts. Jim also wasn’t locating the ball the way he wanted to, and in the third inning the Cards went up 2-0 on three hits and a wild pitch.

“I was hoping we could score some runs early, because I didn’t know how long I could keep my energy level up,” Lonborg says. “I was still throwing decent, but then in the third I gave up a [leadoff] triple to [.227 hitter] Dal Maxvill off the center-field wall. That’s when I knew I was in trouble and that my stuff was starting to flatten out.”

Gibson homered in the 5th, Julian Javier added a three-run blast an inning later, and it was 7-1 St. Louis when Jim struck out Curt Flood to end the sixth. Lonborg doesn’t remember crying as he walked off the mound, but teammates and fans near the Sox dugout could see his tears. It was probably one of the few times a pitcher who had just allowed 10 hits and 7 runs received a standing ovation.

Headlines the next day revealed that Lonborg had asked Williams to keep him in the game just before Javier’s homer (pitcher and manager had both expected a bunt), but there was surprisingly little second-guessing in the days and decades to come. After 297.1 innings and 24 wins, it was accepted that Lonnie had simply run out of miracles. Nine outs later, so had Boston.

What happened next is forever woven into Red Sox lore alongside Bill Buckner‘s muff and Bucky Dent and Aaron Boone homers. After picking up the American League Cy Young Award in a near-unanimous decision, Lonborg signed a 1968 contract for $50,000 (a $30,000 raise), then went to Lake Tahoe, California for some Christmas-time skiing a week later.

He still defends the decision, to a point. “There was nothing in my contract that said I couldn’t ski, and I felt it was the main reason I had been so successful in ’67 — because I was in such great shape. But looking back on it, I didn’t have enough experience to know when it was time to go inside and say you’ve had enough for the day.”

On Dec. 23, making perhaps one run too many, Jim wiped out while attempting a snowplow stop and severely tore ligaments in his left knee. Flown back to Boston with his knee in a cast, he was examined by Red Sox team physician Dr. Thomas Tierney. The doctor recommended surgery to patch the torn ligaments with sutures, but predicted Jim would be back for the start of the 1968 season. It would turn out to be wishful thinking.

Tierney and orthopedic surgeon Dr. John McGillicuddy performed the operation on Dec. 27, and found the injury to be much worse than feared: two ligaments were damaged instead of one. While the surgery was deemed successful, Jim’s pitching future was now more in doubt. He was in a waist-high cast for six weeks, then reported with the team to spring training and a rehab regimen of weightlifting each morning and 27 holes of golf each afternoon.

Lonborg met his goal of a May return, but at a heavy price. In compensating for his knee, he unknowingly altered his pitching motion slightly and placed added stress on his right shoulder. The resulting muscle and tendon damage would plague him the rest of his career.

“They were able to diagnose it as rotator cuff problems, which they really didn’t know how to treat back then,” he says. “I had tons of cortisone shots, and I tried to come back too soon without building up my arm strength properly. It was just a case of youthful energy, and wanting to get back on the field.”

Lonborg made his 1968 debut with a short relief stint on May 28 at Oakland. After four such appearances, he drew his first starting assignment on June 16 in Cleveland. The results were encouraging — five innings, three hits, one run allowed — but he also walked four. His once-stellar control was off; even in throwing six one-hit innings against the Yankees in July for his first win since the World Series, he walked eight. By the start of August, he was just 1-3 with a 5.06 ERA.

There were some encouraging signs down the stretch, including a three-hit shutout of Cleveland in which he struck out nine and walked none. But Jim’s final record of 6-10 and his 4.29 ERA were seen as a major cause for Boston’s fall to fourth place, 17 games behind pennant-winning Detroit. Lonborg hoped another winter of rest would help him turn things around.

For a while, this looked to be the case. Although he had to leave the 1969 season opener after 2 2/3 innings due to shoulder pain, he returned to the rotation three weeks later and by early June was 6-0 with a 2.33 ERA. But he missed three more weeks after breaking his toe on June 21, and then encountered more shoulder woes when he came back. He lost his last eight decisions to finish 7-11, and the Sox wound up third.

The 1970 season was even more frustrating for Jim. He had three strong starts to begin the year, but then his shoulder landed him on the disabled list again. When it failed to come around, management put him on waivers and then sent him to Triple A Louisville on July 23. He made a few starts there, with middling results, and in August was told to go home for the year. Pitching just nine times for the varsity overall, he was 4-1 with a 3.18 ERA.

“Most everybody was hopeful that I would be able to get back to my initial form,” he says in retrospect. “I always felt very good around the clubhouse; my teammates were great, and the Red Sox were very patient with me. I did have flashes of the old stuff, but had not yet learned what it took for my body to heal properly.”

When he was brought back up from Louisville midway through the ’71 season, it appeared Lonborg had figured it out. He went 7-4 the last three months, including 3-1 (with three complete games) in September. His final record of 10-7 with 167 2/3 innings and 100 strikeouts marked his highest totals since 1967, and he felt he was finally “getting a handle on getting healthy.” He was also still just 29 years old.

The Red Sox, however, finished a distant third for the third straight year. Yawkey wanted changes, and on Oct. 10 Boston engineered a 10-player deal with the Milwaukee Brewers in which George Scott, Billy Conigliaro, and Lonborg were among those sent packing for a quartet including pitcher Marty Pattin and speedy leadoff man Tommy Harper. Fans polled mostly felt it was a bad deal, in part because of Lonborg’s promising comeback summer.

“We got the phone call and it was a shock,” recalls Jim. “We loved it in Boston and wanted to stay, and I thought I was really coming around.” He was, but it was not the Red Sox who would benefit.

Lonnie’s last seven full years in the majors are usually an afterthought to armchair historians encapsulating his career, but those who simply say he “never came back” from his ski mishap are neither fair nor accurate. He never again won 20 games, but he was a successful and at times stellar pitcher.

His 1972 season with Milwaukee was a case in point. Pitching 223 innings, often still in pain, Lonborg had a 14-12 record on a last-place team. He had 11 complete games, a 2.83 ERA (the best of his career), and 143 strikeouts. Some of his top performances came against the Red Sox, including a 7-hitter on June 24 in which he registered 11 strikeouts — his most ever for a game not pitched in 1967.

Lonborg enjoyed his year in Wisconsin and was surprised when he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies on Oct. 31, 1972 as part of another massive deal. The Phils had the National League’s worst record in ’72, despite a 27-10 season from Cy Young awardee Steve Carlton. Future All-Stars like Mike Schmidt, Greg Luzinski, Bob Boone, and Larry Bowa were joining the lineup, however, so the promise of better days lay ahead.

Philadelphia wound up improving each of the next four years, and Lonborg played a key role. In 1974 he was 17-13 with a 3.21 ERA over a career-high 283 innings, and was third in the NL with 16 complete games as he and Carlton formed one of the league’s best one-two duos. His hard sinking fastball gone, he became a crafty pitcher who worked the corners and developed a better slider and change-up.

More shoulder woes set Jim back a bit in 1975, but with an 18-10, 3.08 season in ’76 he helped the Phils complete their four-year rise with an NL East championship — their first title of any kind since 1950. He had a sparkling 13-3 mark in home games at Veterans Stadium, and notched the East-clinching victory with a four-hitter at Montreal on Sept. 26.

Nine years after hurling the Red Sox to a title, Lonborg had come full circle. He later called it his best year as a “pitcher” rather than a “thrower,” but it didn’t top ’67. “It was exciting, but it didn’t have nearly the same aura about it. We knew we were going to win the division, and I just happened to be the guy on the mound that night. It wasn’t a ‘win or you’re out’ situation.” Soon Philadelphia was out, however; the Phils were swept 3-0 in the NL Championship Series by Cincinnati, with Lonborg taking the 6-2 loss in Game Two.

The older he got, the harder it was for Jim to shake off his shoulder pain. But he knew when and how to rest now and could still win with consistency. Limited to 25 starts in 1977, he made the most of them with an 11-4 record that included a 10-2 mark in the season’s second half.

One game from this stretch drive stands out. Facing the two-time defending world champion Cincinnati Reds at the Vet on Friday night, Sept. 2, Lonborg learned early in the contest that his wife had gone into labor with their fifth child. Given extra incentive to work quickly, he shut down Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, Pete Rose, and the rest 3-0 and rushed to the hospital in time to see daughter Nora born.

Unfortunately, he didn’t have time to ice down his arm properly after the contest. “I had to sleep at the hospital with my arm propped up in bed, and when I came out to the ballpark Saturday night I could hardly throw a baseball.” In the NLCS a month later, he lost Game Two 7-1 as the Phillies fell in four to the Dodgers. There would be no return trip to the World Series for Jim Lonborg.

The Phils won the East again in ’78, but Jim slipped to an 8-10 mark with a career-worst 5.23 ERA and did not pitch in the postseason. He didn’t expect to even make the team in 1979, but injuries to younger pitchers kept him on the roster for a few months. Appearing in just four games, he made his final major league appearance on June 10 — a 3-inning relief stint vs. Atlanta in which he allowed five hits and three runs.

When Lonborg was released six days later, the event registered just a single line in Boston newspapers. He might have helped another team down the stretch, but didn’t pursue it. He wound up with a fine 157-137 lifetime record in the majors, along with a respectable 3.86 ERA over 425 games. Ironically, his post-Red Sox record (89-72) had been considerably stronger than his Boston slate of 68-65.

New England, however, had been where he made his mark — and his home. Even as a rookie, Jim had been looking to his life after baseball and the opportunity to fulfill his childhood ambition of a medical career. Now, at 37, he returned to Boston to act on those dreams. Taking the advice of his wife Rosie, who “always thought I looked great in uniform,” Lonborg decided to trade his flannels for a white coat and become a dentist.

He put in a year at UMass/Boston boning up on chemistry and other related subjects, then spent three years at Tufts University Dental School, one of the nation’s premier programs. Occasionally he turned heads when younger students recognized him or heard his name called in class.

Still immensely popular in his adopted state, Dr. James Lonborg, DMD, had no trouble finding veteran dentists willing to bring him on. He honed his skills with several, and by the mid-1980s had established his own thriving practice in Hanover, Mass. — a small, quiet community between Boston and Cape Cod. He’s still working there today, and he and Rosie live “about 12 minutes away” in Scituate, in the same house they’ve had since 1975.

Philanthropy has always been important to the Lonborgs, and with old Red Sox teammate Mike Andrews serving as chairman of the Jimmy Fund at Boston’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI), they have been longtime supporters of this charity. Jim has earned recognition as one of DFCI’s leading celebrity fundraisers, and Rosie works part-time in the hospital’s Jimmy Fund Clinic soothing the needs of pediatric cancer patients and their families.

Lonnie has also reestablished strong ties to the Red Sox and was named to the team’s Hall of Fame in 2002. He enjoyed watching from home with his family as the 2004 club made its run to the World Series title, and says seeing them beat the Yankees “was just the best thing in the world.” It was not, however, a case of déjà vu. He knows no matter what happens, ’67 will always be unique.

“People I meet at charity events still tell me they were there when we beat the Twins,” he says. “It doesn’t matter where I am, really. Rosie and I were out in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, this winter skiing, and a guy came up to me and said, ‘I’m sorry to bother you, but I couldn’t help notice the “B” in your ring. That isn’t a World Series ring, is it?’

“It turns out he was just the greatest Red Sox fan in the world. My friends from Arizona watched this young guy of about 38 talk to me about the old days, which he only knew about from stories, and they couldn’t believe it.

“I had to explain to them afterwards that it was something like folklore.”

Author’s Note

This biography originally appeared in SABR’s The 1967 Impossible Dream Red Sox: Pandemonium On The Field, edited by Bill Nowlin and Dan Desrochers, and published by Rounder Books in 2007.

Sources

Jim Lonborg quotes from author interviews of March 2006 and earlier, unless otherwise noted in text.

Assorted Boston Globe and Boston Herald articles, 1965-1979.

Assorted Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Washington Post, and Associated Press articles, 1965-73.

The Impossible Dream Remembered, by Ken Coleman and Dan Valenti.

Red Sox — Where Have You Gone?, by Steve Buckley.

The Picture History of the Boston Red Sox, by George Sullivan.

Three-part series by author on 1967 Red Sox, appearing in Red Sox Magazine, 1992.

Full Name

James Reynold Lonborg

Born

April 16, 1942 at Santa Maria, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.