Bill Slayback

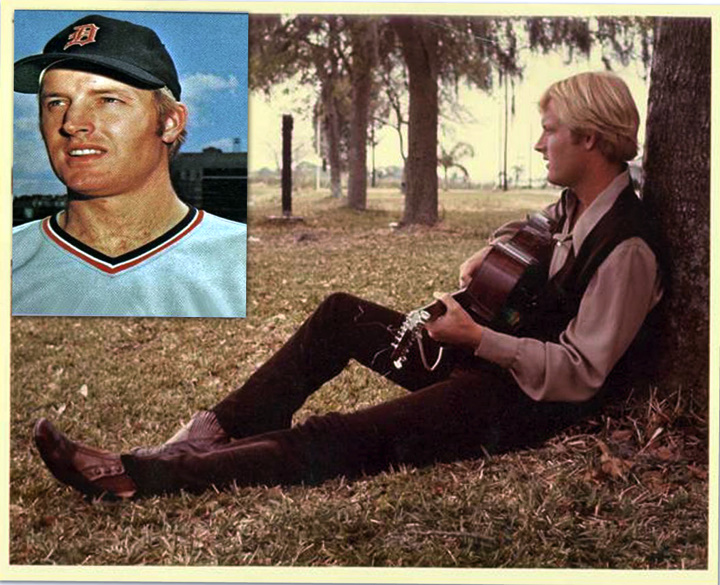

If one wished to find the spiritual reincarnation of prototypical renaissance man Leonardo Da Vinci within the all-time register of major league baseball players, they would do well to consider one William Grover Slayback. Slayback, who walked with the gods of baseball during the summer of 1972 while pitching for the Detroit Tigers, would most likely have impressed Da Vinci. His life outside of baseball included performing professionally as a vocalist and instrumentalist, an artist painting and sketching, and as an accomplished photographer and woodworker. Along the way, Slayback made a name for himself in the commercial world, earning a record of high performance in the world of pharmaceutical sales.

If one wished to find the spiritual reincarnation of prototypical renaissance man Leonardo Da Vinci within the all-time register of major league baseball players, they would do well to consider one William Grover Slayback. Slayback, who walked with the gods of baseball during the summer of 1972 while pitching for the Detroit Tigers, would most likely have impressed Da Vinci. His life outside of baseball included performing professionally as a vocalist and instrumentalist, an artist painting and sketching, and as an accomplished photographer and woodworker. Along the way, Slayback made a name for himself in the commercial world, earning a record of high performance in the world of pharmaceutical sales.

Slayback’s ability to perform both as an athlete and entertainer may have been ordained by first seeing the light of day in Hollywood, California, on February 21, 1948, the son of Nelson and Jean Slayback. Nelson, a combat veteran of World War II, was an executive in the retail business and, perhaps most important for Bill’s athletic career, a baseball player and avid fan. Highly motivated, he acquainted his son early on with the game. Bill’s first memories were of getting baseballs for Christmas and his birthday. When his dad took him and his sister Susie to the park, she was allowed to play on the swing; Bill had to play catch Dad. 1

As Slayback grew up, he was, in his own words, not much of an athlete. Golf and Ping Pong he excelled at; the traditional high school sports — football and basketball — he did not, despite the fact he was rather tall for his age, eventually growing to 6-foot-4. He had one thing going for him: the ability to throw a baseball at 90-plus mph. Slayback may not have known where the ball was going, but it got there fast. He typically struck out 10 or more batters per game — and walked nearly as many. He was scouted because of his fastball — but because he could not control it, interest was minimal.

While Slayback played baseball he was not driven to participate in sports year-round. Slayback’s true passion was in the arts. Describing himself as a dreamer, he was more at home sketching (early on he wanted to be a cartoonist), painting or practicing his guitar hour after hour.

His passion for music led him to form a band in the eighth grade. Throughout high school he and his band regularly performed as an instrumentalist or singer at school dances. So much a performer, Slayback recalls that he never learned to dance. Over the years his ability to play instruments expanded to acoustic guitar, then electric guitar, bass guitar and drums. He practiced music endlessly, “Johnny B. Goode” a favorite — so frequently that his father, into all things baseball, once chided him for practicing in the garage rather than watching the World Series.

After graduating from high school, Slayback went to college seeking a degree in the liberal arts. He still pitched occasionally, not really impressing anyone until one day fate intervened.

His next door neighbor, Bill Gelsinger, who coached a local team (and was also a music buff), found himself without a pitcher for a game and asked Slayback if he could fill in. Bill protested — he had not thrown for some time — but Gelsinger persisted. Slayback, finally persuaded to pitch, not only overwhelmed the opposing team that afternoon with his speed but displayed pinpoint control. After the game he was approached by a scout for the Detroit Tigers to fill out an informational card. He obliged out of politeness, expected nothing and in the next several weeks totally forgot about the incident.

The scout was Jack Deutsch, a former minor leaguer who had signed several players who went on to the majors. 2 After Slayback had long forgotten about the game — or filling out the card — he got a call early one morning from a friend to say he had been drafted. This, at the height of the Vietnam War, was not welcome news. His friend reassured him, “No Bill, you’ve been drafted by the Detroit Tigers!”

And he had been: seventh round in the 1968 draft. The Tigers paid a small bonus and partial college tuition. Slayback was assigned to Batavia in the New York-Pennsylvania League and then to the Gulf Rookie League Tigers. Because Slayback joined the team after his semester ended, he pitched a minimal amount that season. Invited back to pitch for Batavia in 1969, he did extremely well: one earned run in 26 innings, earning a promotion to Lakeland in the Florida State League. There he showed promise with a 4-4 record and 2.62 ERA. He also performed well the next year, although his season was marred by a bout with mononucleosis. Despite this and intermittent arm trouble, he had showed enough promise to be assigned to the Montgomery Rebels in the Double-A Southern League.

At about this time, Slayback heard that Ernie Harwell was looking for him. Slayback had no idea who Harwell was. Harwell, then in the midst of a Hall of Fame career as radio announcer for the Tigers, wanted to meet him not because of his pitching but because of his singing. While Harwell was known for his broadcast abilities, he had a passion for writing music. Harwell and Slayback met, shared experiences and began a lifelong friendship which included collaboration on several songs. Their relationship continued until Harwell’s death in 2010. (Before Harwell’s death Bill collaborated on a song called “When The Dodgers Were In Brooklyn” which portrayed Harwell’s career as a an announcer in the major leagues. The song was actually played by the Oakland A’s as their tribute to Harwell upon his death).

In Montgomery, Slayback further impressed the Tigers. Sporting a 2.95 ERA, he struck out 131 batters in 125 innings, his season cut short by a wart that had developed on the index finger of his pitching hand. 3 Despite the setback, he earned assignment to the Triple-A Toledo Mud Hens for 1972.

Slayback started off poorly in Toledo, largely due to Hank Aaron’s brother Tommie Aaron taking him over the fence several times in the early going. After a rough start, Slayback settled down and by late June was 7-4 with an ERA under 2.50, striking out more batters than innings pitched, indicating his performance the previous season had not been a fluke.

Slayback’s performance constantly improved. On June 20 he threw his fourth consecutive complete game, a three-hit performance. Minor league pitching coach Cot Deal observed, “Slayback should be pitching in the majors. He’s in command of all his pitches, his control is sharp and his mental approach is excellent. He’s never satisfied; always thinks he can improve. If he had pitched a perfect game, he’d probably look for something he could have done better. That’s the kind of competitor he is.” 4 Events in Detroit were swiftly moving to make Deal’s opinion bear fruit.

The 1972 season featured a tight pennant race in the American League East Division with the Tigers, Boston Red Sox and defending AL champion Baltimore Orioles in the hunt. Detroit, with enough hitting to be a legitimate contender, was constantly searching to improve its pitching. After Mickey Lolich (22 wins) and Joe Coleman (19 wins), there was a sharp drop off in quality. General manager Jim Campbell was continually trying to upgrade the staff; by season’s end 20 men would pitch for the Tigers. In late June, based on Deal’s recommendation and Slayback’s performance, the call was made to bring him north.

Slayback’s initial challenge, upon hearing the news, was to first find Michigan, then Detroit. This was accomplished; however, after driving around Detroit for what seemed like hours Slayback could not find Tiger Stadium.

He finally pulled into a gas station to ask directions; his query was met with stunned disbelief. Slayback was only blocks away from and in sight of the looming edifice. When asked whether he was going to the game that night, he said that he had just been called up. Upon learning who he was, the attendant informed him his name was in the papers and on the radio. Slayback was to pitch that night against the Yankees. He was stunned.

A short while later, Slayback entered the Tigers locker room for the first time. He remembers Mickey Lolich introducing himself and welcoming Slayback to the club. Moments later, Al Kaline did the same. Of Kaline, Slayback would later say that all the stories of Kaline’s innate decency are true. He wanted what was best for the team and was always willing to extend himself to a teammate that needed help or guidance. His friendship was genuine – as Slayback would be reminded in dark times, decades after they were no longer teammates.

This spirit of camaraderie was interrupted when Willie Horton came up and asked if he were Slayback. When responded in the affirmative, Horton told him to get into Billy Martin’s office — he wanted to see Slayback immediately. Martin, after greeting the rookie, asked when Slayback last pitched. When Slayback said it would have been his turn in the rotation that day, Martin confirmed he would be starting that night against the New York Yankees.

Slayback made his major league debut, that evening, on June 26, with nearly 31,000 in attendance for a Family Night promotion. The Tigers entered the day tied with the Orioles for the division lead. Slayback was at the top of his game; through seven innings he held the Yankees hitless as the Tigers scored four runs.

During the game, Slayback noticed his new teammates would not talk to him. In the top of the eighth Johnny Callison slapped a single to right. Kaline charged in and fired the ball to first, hoping to nip Callison, but to no avail. Slayback had never seen an outfielder attempt such a play. He said as much to Kaline, impressed by his hustle. Kaline was stunned. “Kid, you didn‘t know what was going on, did you?” When Slayback looked bewildered, Kaline told him he had been pitching a no-hitter; this was why his teammates had been avoiding him. In the ninth inning the Yankees finally began to hit Slayback, who was taken out, the game being saved by closer Chuck Seelbach. With an Orioles loss, Detroit moved into sole possession of first place. It was an impressive and timely debut for the 24-year-old.

Interviewed afterward, Slayback revealed he had the jitters but recalled what Deal had told him about moving up from Toledo: “The mound and the bases had the same dimensions in Detroit. I suddenly realized Cot was right.” 5

Four days later, Martin showed faith in Slayback by starting him against the Orioles. Slayback pitched well, throwing eight innings, ultimately losing 3-2 on a passed ball. Of Boog Powell, who doubled to drive in a run, Slayback was quoted as saying of the massive first baseman, “Powell looks nice — and then he takes that big swing and ruins you.” 6

This performance cemented Slayback as a regular in the rotation. Although he lost his next two starts, he continued to impress, showing self-confidence on the mound. Off the field he was anything but the typical rookie, Watson Spoelstra, in his weekly article for The Sporting News, noted that Slayback “has the kind of poise and humor not often found in a rookie.” Describing a play where a line drive hit his glove, Slayback said, “I knew it had to be around somewhere. By the time I found it the play was over.” 7

Slayback’s interviews invariably included discussion of his love for art and music — this in an era not far removed from when many big leaguers routinely listed their hobbies as hunting and fishing. “I do oils and pastels and all kinds of weird things. I enjoy that, but music is No. 1 right now. I write music and lyrics for the Sandpipers” 8 At that time the Sandpipers were well known for their version of José Fernández Diaz’ hit “Guantanamera” as well as their own “Come Saturday Morning,” an Academy Award-nominated song from the movie The Sterile Cuckoo.

Outside interests aside, his pitching continued to garner attention. In early July, although sporting a 1-3, record he held a 2.04 ERA. It improved over the next three games. On July 12 he held the Texas Rangers to one run in a complete-game effort. Next turn was a five-hit shutout of the Kansas City Royals, succeeded by another five-hit effort against the Rangers in a 5-1 win. In that game, Slayback struck out 13 batters and improved his record to 4-3. His lively fastball and a combination slider-curve or “slurve” each had a breaking movement that befuddled hitters.

His slurve was devastating as a two-strike pitch. Tigers skipper Martin loved calling for it from the bench. Slayback recalled shaking the pitch off several times only to have his catcher call for it again; he then knew he had to throw it on Martin’s orders. On at least one occasion he accidentally threw it on a pickoff throw to first. It broke at the last second, hitting first baseman Norm Cash in the ankle. Cash went out to the mound and told Slayback in no uncertain terms to never throw him a pickoff toss again.

Three days after beating Texas disaster struck. Tom Timmermann started against the Rangers and, after getting just two outs was pulled from the game. Timmerman had pulled a muscle in his side and would miss the next several starts. 9 With three runs in, the game in danger of getting out of control, Martin called on Slayback to shut the door. Martin took a lot of heat later in his career for overtaxing his pitchers; criticism was certainly leveled at him for his use of Slayback. But Slayback, to his credit, explained that Martin had asked him if he was available to pitch. Slayback realized later Martin wanted to know the truth, but Slayback, still somewhat the intimidated rookie, gave the placating response that he was available. Despite being admonished by several in the bullpen — he had just pitched a complete game a few days before — Slayback went in. He managed to hold Texas to just one hit through the fifth. After having just pitched three consecutive complete games, and coming into this game on short rest, he overtaxed his arm. Something just gave way; it wasn’t just one pitch, it was the overall effort. His fastball was no longer “alive.” 10 At this point he had a spectacular 1.40 earned run average, best in the league, although he hadn’t pitched enough innings to qualify. Little did he know it, but his days as an effective major league pitcher were over.

In today’s environment, it is probable Slayback’s pitching might have been more closely monitored. In less than a month he had pitched nearly 60 innings. Prior to that he had never thrown more than 125 innings in a season. Recalling having experienced arm problems in the minors, Slayback remembered while with Lakeland in 1970, that manager Dick Tracewski was concerned he had thrown too many pitches. But Tracewski’s caution was the exception at that time, not the rule.

Baseball at that time did not have an understanding of pitching dynamics as in today’s game. A good deal of pitching “expertise” rested with coaches who often served as nothing more than the manager’s drinking buddies. Stories of these patterns of behavior are redolent during this era. 11 A pitcher like Slayback, with a history of recurring difficulties, was susceptible to overuse. Upon looking back, he is philosophical — it was just how things were at the time.

Several weeks later, Martin, always the instigator, decided he would shake things up as the Tigers were engaged in a tight race. Playing the Oakland A’s in Detroit, Martin became upset when Oakland started to hammer the Tigers. Slayback was called in to relieve and a few batters into his appearance Martin ordered him to hit outfielder Angel Mangual. Slayback, never having purposely hit a batter, was stunned. Hesitant, he asked Detroit catcher Duke Sims what he should do, and Sims advised that if he didn’t follow Martin’s order he was likely on his way back to the minors. With that, Slayback threw behind Mangual. Narrowly missing Mangual’s head, the ball rolled to the backstop. A fight immediately broke out; after order was restored Slayback, Tigers infielder Ike Brown and Mangual were all tossed out of the game.

Martin told Slayback to come into his office after the game and proceeded to tell Slayback he had a lot of guts and that Martin would pay Slayback’s fine for being tossed. He also said he would try to get Slayback a raise. Slayback kept his mouth shut, not wishing to tell Martin the wild pitch was an accident; he had determined he would not throw at Mangual. In light of what was to come, one can speculate that this incident contributed to Bert Campaneris’ throwing his bat at the Tigers’ Lerrin LaGrow in the AL Championship Series a few months later, which caused him to be suspended the balance of the series.

Slayback, commenting a few days later on the fight thought he had held his own in the melee, , “then I saw the newspaper pictures and I hurt all over.” As was the case with many on-field brawls he was mystified as to who was fighting whom. The day after it was over Mangual, with whom he had scuffled, came by, waved his hand and with a smile said “Amigo?” Slayback grinned back and responded “Si.”

Virtually every game Slayback pitched the balance of the season resulted in an unproductive performance. The Tigers finished a half-game ahead of the Red Sox to win the AL East margin owing to the Tigers playing one more game than the Bosox in a strike-shortened season. Slayback was used sparingly down the stretch and didn’t really feel part of the team. The night the Tigers clinched the pennant, Slayback was called upon to sing. It was the first time many of his teammates had heard him perform. They were sincerely impressed; after that evening, Slayback felt accepted. Of his singing, Martin offered a compliment, “After hearing Slayback, Norm Cash sounds like a truck driver.” 12

The Tigers lost to the A’s in the AL Championship Series three games to two, a series marred by Campaneris’ bat-throwing incident. Slayback did not appear in the series; his now-obvious ineffectiveness posed too great a risk. For the season, Slayback ended 5-6 with a 3.20 ERA, a performance belying his early, spectacular success.

During the offseason, Slayback attended college at night and sang in local supper clubs. Things were made considerably easier when he was awarded a full share of the Tigers’ division championship winnings — $6,859.77 — despite only having only pitched a portion of the year in the majors. He later learned Kaline, Martin and others had spoken up on his behalf — an action that deeply affected him. Despite his injured arm the Tigers thought well of his future. During the offseason whenever prospects for 1973 were discussed, Slayback was consistently and prominently included in their plans.

With the advent of spring training, however, it was obvious Slayback’s arm was bothering him. Ineffective, he was assigned to Toledo to work things out with what was described as a tender elbow. His performance at Toledo was subpar: 2-6, 5.03 ERA reflected. Called up by the Tigers in June, he pitched poorly in three games before being sent back down.

In 1974, Slayback, realizing the pitches that got him to the majors were gone, worked on developing a sinker. It was a success — he had the best ERA of any pitcher during preseason games. Ralph Houk, now managing the Tigers, had been watching Slayback and was convinced he could bring him back to be the pitcher who had stymied the Yankees in Slayback’s major league debut. Houk called him into the office one day to give a pep talk beginning with, “Remember that game you pitched against us…” Slayback made the team and would stay with the Tigers the whole season.

At this time, the eyes of baseball were on Hank Aaron in anticipation of his breaking Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record. Slayback and Harwell had been anticipating the milestone as well; the previous summer they began work on a song to commemorate Aaron’s impending achievement. Harwell developed lyrics and Slayback the music for “Move Over, Babe” and they recorded it. It proved a timely hit at the time, honoring Aaron’s efforts:

Move over, Babe. Here comes Henry and he’s swinging mean;

Move over, Babe. Hank’s hit another; he’ll break that 714.

“Move Over, Babe” gained play on national television. Whenever Aaron came to bat on a televised game, Curt Gowdy and Tony Kubek played the song. It didn’t hurt that Aaron stalled out at 713 four-baggers at the end of the 1973 season, giving the tune an extended shelf life. The song did little for Slayback’s pocketbook; at one point he admitted to having earned just $135, but its popularity helped make his reputation in the music industry.13

Meanwhile, the Tigers were having a difficult time of it, playing substandard ball and ultimately finishing last. It was the final year for Cash and for Kaline, who reached 3,000 career hits in the waning days of the season. Other than Kaline’s well-deserved accomplishment there was nothing much else the team could take pride in.

Slayback started well; in his first appearance of the season he pitched seven innings of two-hit scoreless ball against the Orioles. As the season progressed, however, his appearances as a reliever and spot starter became less frequent. At one point he did not make an appearance in more than six weeks. He did pitch against Texas once. Martin, now managing the Rangers, was yelling at Slayback. It took a while for Slayback to understand that Martin was not heckling him but encouraging him to do better — one of the hurler’s oddest experiences in baseball.

Appearing in a game was rare; Slayback recalls sitting in the bullpen day after day for the call seldom made. His pitching suffered from nonuse. Appearing in just sixteen games, he compiled a 1-2 record with a 4.77 ERA. On the last day of the season, Slayback ended the season as he it began; shutting down the Orioles for several innings. It was only his third appearance in a month and a half — and his last as a major leaguer.

Shipped out to Evansville in the American Association for 1975, Slayback joined a team that won the Junior World Series title. He finished the season with a 9-11 record — not good enough to gain a call-up to Detroit, but encouraging enough to plan for the 1976 season. His roommate for the Triplets late that season was a 21-year-old right-hander whose mannerisms were as odd as his talent was supremely apparent: Mark Fidrych.

The 1976 season was Slayback’s last as a professional player. Finishing 3-13 with Evansville, he decided it was time to quit. Although Detroit wanted him to return, Slayback felt it was not feasible for him to continue. At the same time, his interest in and connections with the music industry allowed him to work under contract with Sergio Mendez (of Brasil 66 fame) for two years, and, for a season, tour alongside blind Puerto Rican folk-rock guitarist José Feliciano. Slayback’s talent as a songwriter and musician led to making commercials for Budweiser, Miller and Nike. But sis, skills in music, photography painting were not enough to sustain a livelihood.

A friend, knowing Slayback was seeking a more secure future for his wife and daughter, invited Bill to come with him on his rounds as a pharmaceutical sales representative. Slayback took him up on the offer, beginning a 30-year career in the field. A professional acquaintance and later friend, Gary Sadler described Slayback’s approach to his new vocation:

“Bill, like many athletes that reach the highest level is very competitive. I think this helped him be successful within the medical industry. Pro athletes are also good goal setters. They can visualize what they need to accomplish and put together a plan to achieve it. Bill believes in always improving basic skills and learning new ones; much like a ballplayer always looking for ways to improve mechanics and get better.” 14

Slayback obtained a master’s degree in marketing from California Lutheran University to enhance his sales skills. His easy and engaging manner as well as exhibiting a consistent enthusiasm proved a major asset in meeting with clients, both active and potential. This, coupled with an ability to gain an understanding of new disciplines served him well in learning about the complex relationship between doctors, patients, and rapidly developing medical technologies. Slayback was consistently sought after for his sales abilities.

After 25 years in the industry, Bill retired in 2008. Slayback, always active, formed Slayback Productions, which among other functions is available for various corporate functions. When not working, Slayback can be found with his dogs, camping at Rock Creek Lake in Southern California. He continues to participate in various events connected with baseball such as when he sang “The Star-Spangled Banner,” first at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles then at Comerica Park in Detroit for the Tigers’ “Sparky Anderson Day” celebration during the 2011 season.

Bill Slayback has talents that would make giants of the Renaissance era blush. While he could throw a 96 mph fastball, he performed on a par with those at the highest level of talent within the music industry and distinguished himself in a tough sector of the business world. Although extremely talented, perhaps his greatest accomplishment is the respect he has earned from a legion of friends made along the way.

Twice married and now single, he fathered three daughters, Heather, Kelli and Samantha. In keeping with their dad’s ability to take on different vocations, Heather became president of a construction company, while Kelli, having earned an MBA, established a successful career in the aerospace industry. Samantha, just starting college, has yet to chart her course for the future, but she certainly does not have to look far for inspiration to know anything is possible.

Bill lost his daughter Heather suddenly and unexpectedly in November 2011. The loss of a child is staggering and incomprehensible to a parent. His friends did not desert him. Al Kaline, Gene Lamont, Jim Leyland – the latter two Tigers draftees in the 1960s like Slayback who 40 years later would form the on-field brain trust for Detroit — and umpire Joe West were among lifelong acquaintances who reached out, not to just offer perfunctory condolences but to listen, and to support Bill. Their attempts to comfort Bill speak volumes of how well he is regarded as a human being.

Epilogue

Bill Slayback was found dead on March 25, 2015, in his Los Angeles home, according to the Detroit News. He was 67.

Notes

1 Various interviews with Bill Slayback between September 2011 and February 2012 provided much of the information for this article. Thanks also to Liz Erion and Gary Sadler for their assistance in arranging for these interviews to take place.

2 Among Deutsch’s signees with major league experience: Dennis Saunders and John Young founder of Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities (RBI). Deutsch would later be selected The Sporting News Coach of the Year in 1977 for his performance at Cal State-Los Angeles.

3 Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, July 14, 1972, C-6.

4 The Sporting News, July 8, 1972, 36

5 The Sporting News, July 15, 1972, 5

6 The Sporting News, July 22, 1972, 9

7 Ibid.

8 The Sporting News, July 15, 1972, 5

9 The Sporting News, August 26, 1972, 8

10 Slayback interview.

11 See for example Peter Golenbock’s Red Sox Nation (Triumph Books, Chicago, 1992) or Wrigleyville, (St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1996)

12 The Sporting News, September 16, 1972, 8.

13 The Sporting News, April 27, 1974, 28.

14 Email from Gary Sadler, December 17, 2011.

Full Name

William Grover Slayback

Born

February 21, 1948 at Hollywood, CA (USA)

Died

March 25, 2015 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.