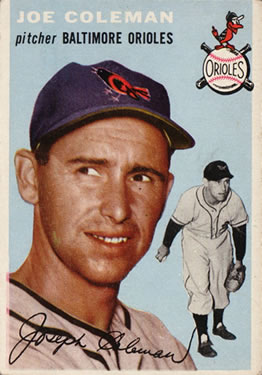

Joe Coleman (the Elder)

In the late 1930s, Malden (Massachusetts) Catholic High School principal Brother Gilbert, the same Christian servant who had recommended George Herman Ruth to Baltimore Orioles manager Jack Dunn two decades earlier, believed he had hit pay dirt again. He arranged a meeting between righthanded phenom hurler Joe Coleman and his former protégé. “Pleased to meet you, kid,” said [Babe] Ruth to the goggle-eyed Coleman. “Brother Gilbert tells me you’re gonna be a great pitcher some day.”1 Many would reach the same conclusion throughout the next decade before a freak injury halted the youngster’s ascent.

In the late 1930s, Malden (Massachusetts) Catholic High School principal Brother Gilbert, the same Christian servant who had recommended George Herman Ruth to Baltimore Orioles manager Jack Dunn two decades earlier, believed he had hit pay dirt again. He arranged a meeting between righthanded phenom hurler Joe Coleman and his former protégé. “Pleased to meet you, kid,” said [Babe] Ruth to the goggle-eyed Coleman. “Brother Gilbert tells me you’re gonna be a great pitcher some day.”1 Many would reach the same conclusion throughout the next decade before a freak injury halted the youngster’s ascent.

Joseph Patrick Coleman was born on July 30, 1922, the fifth of six children of Joseph P. and Julia Elizabeth (Shaughnessy) Coleman, in Medford, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston. He was the great-grandson of David Coleman, an Irish immigrant who around the time of the American Civil War arrived in a region of Worcester County, MA, approximately 10 miles south of the New Hampshire state line. In 1910 David’s grandson, the ballplayer’s father, married Julia in The Granite State. Around 1920, the family moved to the Boston suburbs. Aside from owning a poolroom for a brief period in the 1920s, Joseph supported his family as a fruit and tobacco salesman.

The Coleman children may have been fans of the local Red Sox or Braves teams but their father, who shared a Worcester County birthplace alongside Philadelphia Athletics owner-manager Connie Mack, was an avowed A’s fan. When the big league teams began showing interest in his second youngest son in the 1930s, Joe Coleman insisted that he “wouldn’t listen to offers from any other . . . ‘I want you to go to Connie Mack,’” he told his son.2 Mack’s glowing assessment of the kid several years later—“Coleman has two great pitches . . . a steaming fastball with a lot of life in it, and a . . . fast curve.”— showed reciprocal interest.3 Moreover, the father’s determined stance suited the tightfisted skipper perfectly well. After the youngster’s brief fling at Boston College in 1940, the future Hall of Fame skipper was able to sign Coleman without paying him a bonus.

In 1941, Coleman was assigned to the Class-C Newport News Pilots in the Virginia League. Under the tutelage of the Athletics former mound ace Chief Bender, Coleman, one of the youngest players in league, placed among the circuit leaders in several categories including wins (15), appearances (32), starts (26), and innings (223). Invited to the Athletics training camp the following spring, his resume of strong performances included a combined no-hitter with two others that earned Coleman an advance to the franchise’s highest minor league affiliate, the Class-A Wilmington (Delaware) Blue Rocks in the Interstate League. After establishing near league leading marks in wins (18) and ERA (2.32), the 19-year-old was called up to the big club in September.

On September 19, 1942, Coleman made his major league debut at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park in the second game of a doubleheader against the Washington Senators. Entering the second inning in relief of righthander Dick Fowler, Coleman retired the first five batters in order in route to a respectable six inning effort. If this fine performance gave Mack hope that he could insert Coleman into the rotation the next year, those hopes were dashed in November when, 11 months after the U.S. entry into the Second World War, the Massachusetts native enlisted at the Naval Aviation School at Amherst College alongside Boston-based major leaguers Ted Williams, Johnny Pesky, Johnny Sain and Buddy Gremp. The following spring Coleman, Sain, and Pesky, transferred to Chapel Hill, NC for additional flight training, made up the core of the successful NC Pre-Flight Cloudbusters baseball team. Coleman was subsequently sent to the naval base in Corpus Christi, TX before serving out the war in the Pacific Theatre. He was honorably discharged in the fall of 1945.

In 1946, Coleman reported to the A’s spring training alongside a large corps of young pitchers. Despite having “done exceptionally well” in Grapefruit League play, he was eventually optioned to the Triple-A Toronto Maple Leafs in the International League.4 On April 25, Coleman made his circuit debut in exceptional style with a four-hit shutout against the Newark Bears, the first of a league leading five whitewashes that he shared with Syracuse right-hander Earl Harrist. Among the league leaders in nearly every pitching category, Coleman figured prominently in the circuit’s MVP balloting.

Coleman, as a late-season call-up for the A’s, made his first major league start in a game against the Indians in Cleveland. He was fortunate to surrender just two runs after yielding six hits and four walks in three-plus innings while absorbing his first big league loss. He fared even worse in an equally abbreviated start against the Detroit Tigers four days later when he also took the loss. In his last two appearances of the season, he fared better. He pitched a perfect four innings against the Yankees on the last day of the season, and four days earlier, on September 25, a triple play helped him hold Washington to one run in three innings. During the offseason, A’s assistant manager Earle Mack predicted that the team would be “counting on Coleman . . . [as a] certain starter” during the next season.5

Mack’s words proved prescient when Coleman joined a rotation of fellow youngsters Dick Fowler and Bill McCahan in 1947 that helped the franchise to its first winning season in 14 years. Following an 8-4 win against Boston Red Sox on July 3, the Athletics trailed the first place New York Yankees by only 6½ games, a turnaround that Yankee coach Chuck Dressen credited to “the best pitching staff in baseball.”6 Though Coleman’s contributions appeared pedestrian (3-5, 3.81 through June), they did include two complete game wins against the Bronx Bombers, including his first major league shutout on May 30. Much more was expected from the youngster when the Athletics resumed the pennant chase following the July 8 All Star Game.

But except for a second shutout on August 15 against the Senators, Coleman was anything but productive: he went 2-7, with a 5.23 ERA over his last 94⅔ innings. Part of the problem was surrendering nearly twice as many home runs as he allowed in the first half, finishing with a near league leading 17 dingers total. Connie Mack, who attributed the tumble to Coleman’s adding another off-speed pitch to his repertoire, would insist that the youngster abandon the pitch the next year.7

This advice proved wise when Coleman, after winning each of his six starts in May 1948, tied for the league lead in wins at the end of the month alongside Yankee righthanders Vic Raschi and Allie Reynolds. Selected with battery mate Buddy Rosar as the Athletics only representatives in the July 13 All Star Game, Coleman worked the last three innings of the Midsummer Classic yielding just two walks and no hits to preserve the AL’s 5-2 win. Then within a three-week span beginning July 17, Coleman pitched three shutouts. Though he struggled in several other appearances in the second half, Coleman finished among the Athletics leaders in wins (14), appearances (33), innings (215⅔), complete games (13) and strikeouts (86). In October, in the first of several off-seasons, he joined the Birdie Tebbetts All Stars in an 11-game barnstorming tour throughout portions of Canada and New England. Two months later the Athletics soundly rejected an offer to trade Coleman to the Yankees for All Star second baseman Snuffy Stirnweiss.

Brother Gilbert’s predictions of Coleman’s future greatness appeared to have come to fruition in 1949 when the 26-year-old opened the season with five wins and a 2.41 ERA through his first nine appearances of the season. Though he struggled in June and July, Coleman seemed poised to finish the season on a strong note when he took the mound on August 23 against the Chicago White Sox after winning three of his previous four decisions. In the second inning Coleman, a fair hitter, hit his first major league home run, a two-run shot against lefthander Mickey Haefner. After reaching base again on a single in the 8th, Coleman wrenched his right shoulder after tripping over the third base bag. He was lifted in the bottom half of the inning after facing just one batter. Despite concerns that he had torn a ligament in the shoulder, Coleman insisted on remaining in the rotation. He finished the season with career-high marks in complete games (18) and innings pitched (240⅓) while tying his career threshold of 33 appearances. On the downside, he also established a personal single season high 127 walks.

Coleman’s record through five complete seasons hardly dissuaded interest in him from other major league teams. The New York Yankees were again the most aggressive in pursuing him. In November and again in March they offered several packages to the A’s, one that included veteran Phil Rizzuto, for Coleman. But concerns about Coleman’s physical condition proved accurate when the righthander reported to the 1950 spring training complaining of a sore arm. “Able only to shotput the ball,” Coleman was sidelined through most of the season’s first half and finished the year with an unsightly record of 0-5 and 8.50 ERA in 54 innings (15 appearances).8

Athletics pitching coach Chief Bender, Coleman’s first professional manager, noticed marked improvement in the righthander’s delivery the following spring. Hardly alone in this observation, Red Sox GM Joe Cronin, after receiving favorable reports on 28-year-old’s progress, was compelled to deny a rumor that he had engaged the A’s in talks that would have sent slugger Ted Williams to Philadelphia for Coleman, lefthanders Lou Brissie and Bobby Shantz, and All Star first baseman Ferris Fain. And although the regular season started well, it quickly faded to disappointment when Coleman compiled an 11.81 ERA in seven starts through June 10. Relegated to the bullpen for the rest of the season, he finished the year dismally: 1-6, 5.98 in 96⅓ innings.

Though Coleman reported to the Athletics 1952 spring training again healthy and pain free, he had a mediocre spring training. In April, he was assigned to the Triple-A Ottawa (Ontario) A’s in the International League. “I felt certain this year he’d come back,” A’s manager Jimmy Dykes, said after the demotion. “Now, I’d be afraid to use him in a regular game unless the cause was absolutely hopeless—and what good would that do Joe?”9 Coleman’s struggles followed him to Ottawa, and he was again demoted to Class-A Savannah of the Sally League. Though he returned to Canada in August after injuries decimated the A’s staff, the return did little to improve Coleman’s fate as he finished the season with a combined record of 3-19, 4.44 in 160 minor league innings. “[T]hough his won-loss record was nothing to speak about . . . he pitched a lot of good ball,” said A’s GM Art Ehlers, putting the best face he could on a truly miserable season.10 Instead of barnstorming throughout New England during the offseason, Coleman took up a winter residence in Florida in hopes that the warmer clime would help his arm.

Through sheer perseverance (and perhaps the warmer weather) Coleman returned to the major leagues in 1953. No longer possessing his once-blazing fastball, the righthander earned his way back onto the Athletics roster through guile and willpower. But Coleman’s promising rebound was soon interrupted by an emergency appendectomy in May that sidelined him for two months. Upon his return, Coleman was used in relief and as a spot starter for the rest of the season. Included among his 21 appearances was an August 13 shutout of the Red Sox followed more than a month later by a 9-2 complete game win against the Senators on the last day of the season. Ehlers noted these two fine performances and on December 17, shortly after being hired as the Baltimore Orioles GM for the club’s inaugural season, acquired Coleman and lefthander Frank Fanovich from the Athletics for veteran lefty Bob Cain.

Attempting to build on the success over the previous offseason, Coleman spent a portion of the winter playing ball in Cuba. Pitching primarily in relief for the Havana club, Coleman accumulated eight wins, near the league lead, before taking a line drive off his knee. Upon learning of the injury, Ehlers immediately pulled Coleman and 11 other Orioles out of the Cuban Winter League. When the injury proved minor, Coleman, who had perfected a sinker and slider to go along with his curveball, proceeded to the finest spring training of his career.11

Soon being touted as a “candidate for comeback of the year honors” for his fine spring, Coleman delivered the Orioles first shutout on May 11, and he twirled a 5-3 complete game win against the Senators eight days later to lift his record to 4-2 with a miniscule 1.81 ERA.12 Dubbed “Discarded Joe” in July after Yankees manager Casey Stengel bypassed Coleman for the AL All Star team, the veteran righthander shrugged off the slight. “I’m more interested in winning for Baltimore . . . I think I can win 15 or more. Maybe 18 or 20.”13 He was a bit optimistic. Although he remained popular among the Orioles fans, Coleman lost 10 of 11 decisions through August 25. On July 30, Coleman’s 32nd birthday, a crowd of 27,385 packed into Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium where Maryland Governor Theodore Roosevelt McKeldin presided over a pre-game celebration. A month later, following five weeks of balloting, Coleman was selected as the fans’ choice for favorite Oriole.

On September 9, an eighth inning bad hop infield single by future Hall of Famer Enos Slaughter was the only thing barring Coleman from a no-hitter when he blanked the Yankees 1-0, his second shutout in three starts. Asked about the hit afterward, Coleman cracked, “I can’t tell you my exact words, but they were slightly on the blasphemous side.”14 He finished the season among the circuit leaders in several categories including innings pitched (221⅓), starts (32), complete games (15) and shutouts (four). He also achieved the finest single season WHIP (1.265) of his career that year. The only downside to his season was his17 losses, which could largely be attributed to the lack of run support he received from the Orioles punchless offense. During the offseason, the Boston BBWA selected Coleman as the Outstanding Major League Comeback Player of 1954.

Unfortunately Coleman reported to Orioles 1955 spring training with arm problems again. Following a difficult grapefruit league season, Coleman managed only a pitiful record of 0-1, 10.80 in 11⅔ innings throughout the first three months of the regular season. On July 1, after turning down a scouting job with the O’s, Coleman received his release. A week later he signed with the Tigers where he achieved some success working exclusively in relief: five hits and no runs in his first 10 innings. On September 7, Coleman pitched the eighth inning against the Red Sox in a mop-up role. It proved to be his last major league appearance.

On April 9, 1956, Coleman was among the Tigers last cuts when he was released by the club. He signed with the Buffalo Bisons in the International League where, again working exclusively in relief, he compiled a middling record of 4-2, 4.22 in 79 innings. The following spring, the San Diego Padres in the Pacific Coast League bought Coleman’s contract, and he retired shortly thereafter when he did not make the team.

Coleman returned to Massachusetts where he was reunited with his wife of 13 years, the former Barbara Colby. They had one son, Joseph Howard Coleman, whom the Washington Senators selected in 1965 in the first round of the inaugural major league draft. After Coleman negotiated a $75,000 signing bonus for his son, there was some talk about his joining the Senators as a fulltime scout. (It is unclear if Coleman ever scouted for any team.) In 1966, after having served as the athletic director for the Massachusetts Department of Corrections and the Boston-based Young Men’s Christian Union, Coleman partnered with his son in a sporting goods store in Natick, MA. On several occasions, he also appeared at Fenway Park to pitch batting practice for the Red Sox.

Throughout his playing career, Coleman lent his time to varied non-profit community organizations including several youth-based baseball programs. This outreach extended well into his retirement. In 1958, Coleman joined several ex-major leaguers in the Mayor’s Charity Field Day exhibition game at Fenway Park. He was also a favorite on the rubber chicken circuit both during and after his career. In June 1970, Coleman travelled to East Brookfield, MA, to participate in the celebration of city’s native-son Connie Mack. Four years later, he returned to Baltimore for the 20th anniversary celebrations of the 1954 Orioles inaugural team.

In 1972, Coleman’s son was selected to represent the AL in the All-Star Game, only the second time in major league history that a father-son combo had been selected for the honor. When Coleman’s grandson Casey put on a Chicago Cubs uniform 38 years later, it represented the first and, through 2017, only time the major leagues have had three generations of pitchers. Unfortunately, Coleman was not around to witness this. Having moved to the Sunshine State around the 1980s or ’90s, he died in Fort Myers, Florida, on April 9, 1997, two months shy of his 75th birthday. He was buried at the Fort Myers Memorial Gardens.

Coleman concluded a 10-year major league career with a pedestrian record of 52-76, 4.38 in 1,134 innings (223 appearances). If not for a freak baserunning accident in 1949, so much more appeared to be in store for the hard-throwing righthander.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Kelly Dugas, a family historian and distant cousin of the ballplayer, for her valuable assistance. Further thanks are extended to SABR member Tom Schott for review and edit.

This biography was fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Notes

1 Herb Heft, “Coleman Climbs High Comeback Cliff,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1954: 8

2 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Mack’s Cinderella A’s Cost But $75,000,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1948: 3.

3 Art Morrow, “Mack Criticizes Heavy Schedule of Exhibitions; Likes Isolation of A’s,” The Sporting News, March 31, 1948: 10.

4 Stan Baumgartner, “Athletics’ Bats Still Apathetic,” March 28, 1946, The Sporting News,: 16.

5 Stan Baumgartner, “Phillies High on Hill, 15 Range Over 6 Feet,” The Sporting News, February 26, 1947, 6.

6 “Dressen Claims Pitching Produced Homers in N.L..” The Sporting News, October 8, 1947: 27.

7 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Mack’s Cinderella A’s Cost But $75,000,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1948: 3.

8 Art Morrow, “A’s Comeback Hope Depends on Pitching,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1950: 6.

9 Art Morrow, “Connie, 89, Sees Something New—Pilot Jim’s Office,” The Sporting News, April 23, 1952: 16.

10 Art Morrow, “A’s Ready to Deal—Even Shantz—But Won’t Give Anything Away,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1952: 32.

11 Coleman later admitted that the spitball also became a part of his repertoire.

12 “American League: Games of Wednesday, May 19,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1954: 22.

13 Hugh Trader Jr., “Baltimore Burns at Case’s All-Star Snub of Coleman,” The Sporting News, July 14, 1954: 18.

14 Hugh Trader Jr., “’Bad Hop’ Single Spoils Coleman’s Bid for No-Hitter,” The Sporting News, September 15, 1954: 15.

Full Name

Joseph Patrick Coleman

Born

July 30, 1922 at Medford, MA (USA)

Died

April 9, 1997 at Fort Myers, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.