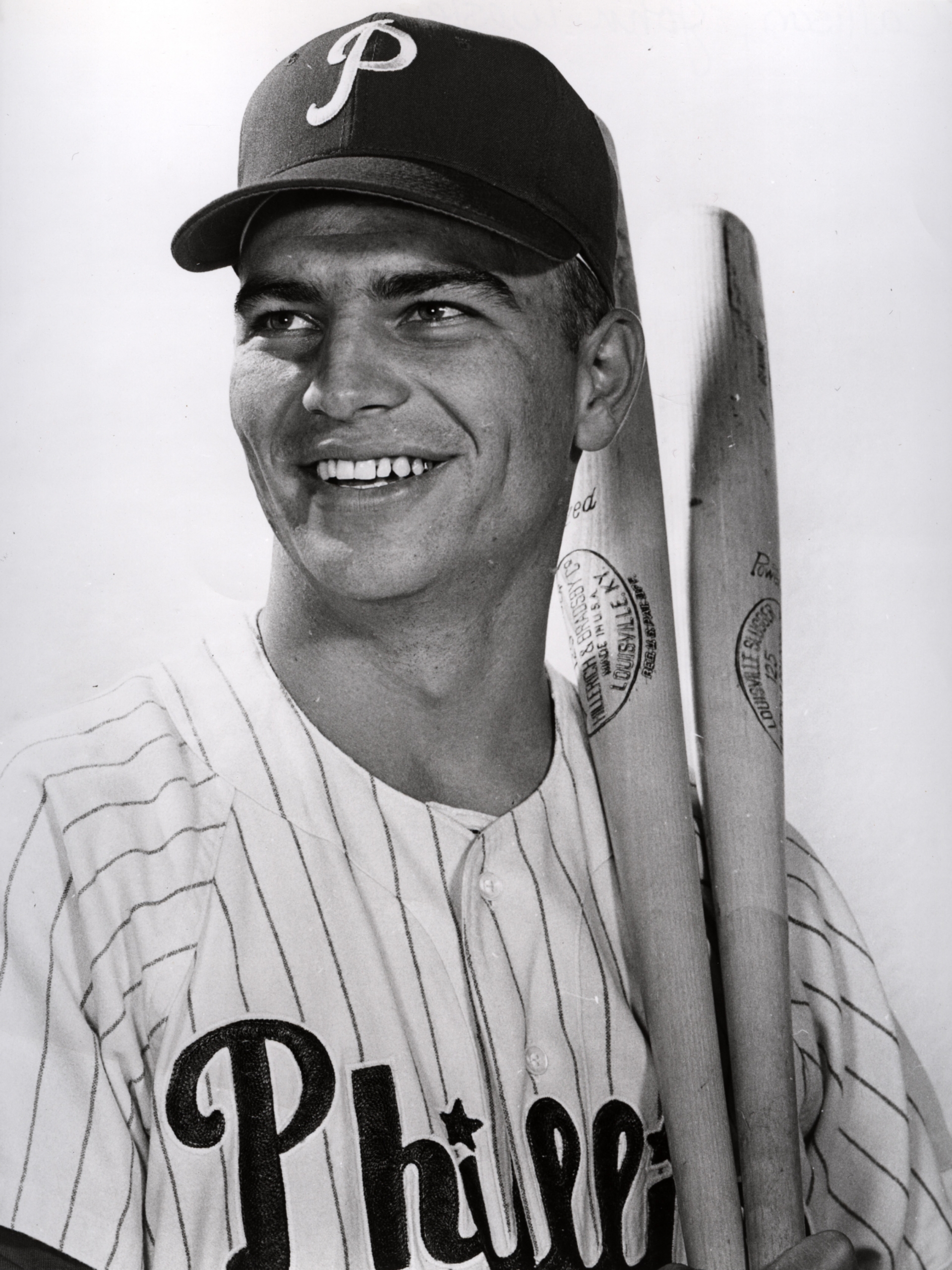

Johnny Callison

Early in his 16-year major-league career, Johnny Callison was labeled “the next Mickey Mantle.” His manager with the Phillies, Gene Mauch, said Callison could “run, throw, field, and hit with power. There’s nothing he can’t do well on the ball field.”1 These encomiums proved burdens that the always sensitive Callison found difficult to live up to. His career, spent briefly with the Chicago White Sox and then for ten years with the Phillies before finishing with short stays with the Chicago Cubs and New York Yankees, was marked by what-ifs and what might-have-beens.

Early in his 16-year major-league career, Johnny Callison was labeled “the next Mickey Mantle.” His manager with the Phillies, Gene Mauch, said Callison could “run, throw, field, and hit with power. There’s nothing he can’t do well on the ball field.”1 These encomiums proved burdens that the always sensitive Callison found difficult to live up to. His career, spent briefly with the Chicago White Sox and then for ten years with the Phillies before finishing with short stays with the Chicago Cubs and New York Yankees, was marked by what-ifs and what might-have-beens.

John Wesley Callison was born in Qualls, Oklahoma, on March 12, 1939, the son of Virgil (sometimes spelled Vergil) and Wilda (Faddis) Callison. The family supposedly had Native American roots. The Callisons were poor and his father worked odd jobs in and around Qualls in the dying days of the Great Depression. When Virgil joined the Army during World War II, Callison’s mother traveled the path of many “Okies” before her and in 1944 took young Johnny, his brother, and his two sisters and settled in Bakersfield, California.

The quiet and shy Callison discovered that he had exceptional athletic skills. One of his teachers noted that he could run faster backward than most of his classmates could run forward. Sports became his way out of a life of poverty and hardscrabble work. He said later in life that he “found my refuge in baseball” because only on the ballfield did he feel “worthy of measuring up.”2

Callison was a star athlete at East Bakersfield High School and especially stood out in baseball. The scouts were on his trail before he graduated from school, with the White Sox eventually signing him in 1957 for a bonus of $7,000 plus another $3,000 under the table. To ease his way into professional baseball, the White Sox assigned the 18-year-old Callison to his hometown team, the Bakersfield Bears of the Class C California League.

Callison made an impressive debut in 1957, hitting .340, rapping out 41 extra-base hits, and stealing 31 bases in just 86 games in a league that included such future major leaguers as third baseman Charlie Smith, pitcher Chuck Estrada, and outfielder Vada Pinson. Callison was named the league’s outstanding rookie. The White Sox brass believed they had a superstar in the making and the next season jumped him all the way to their Indianapolis Indians team in the fast-paced Triple-A American Association. At 19, Callison was one step from the majors.

Callison’s sophomore season saw the first comparison to his fellow Oklahoman, Mickey Mantle.3 While Callison’s average dipped to .283, he led the league with 29 home runs and drove in 93 runs while showing for the first time a cannon-like throwing arm. In September the White Sox brought Callison up for a taste of major-league life. He showed signs that he was ready for the big time by hitting .297 while driving in 12 runs in 18 games. The pitching-strong White Sox, who finished 10 games behind the Yankees in 1958, believed that they had a chance to win the pennant the next season. They brought Callison to spring training hoping that he would add some punch to their weak offense.

Callison made the team out of spring training but was a major disappointment, hitting just .173 with three homers in 49 games. He was sent back to Indianapolis in midseason. The always-competitive Callison was disgusted with himself and felt he had let the White Sox down. The White Sox brass decided that they needed to add offense to continue to compete with the Yankees; despite winning the pennant, they had finished last in the American League in home runs and sixth in batting in 1959. Callison became expendable.

In the offseason, the White Sox made two major trades to add power to their lineup. They got former home run champ Roy Sievers from Washington to play first base and exchanged Callison for third baseman Gene Freese, who had hit 23 home runs for the last-place Philadelphia Phillies.

The trade proved the making of Callison. Going to a developing team where there was no pressure to perform and especially coming under the tutelage of Gene Mauch, he blossomed into one of the premier players in the National League.

Callison’s best years were with the Phillies from 1960 to 1969. His first two seasons were a learning process. Mauch loved his potential and made him a special project. In some ways, Mauch saw Callison as the kind of ballplayer he would have liked to be. Callison was not only Mauch’s special project but also his pet. Mauch worked on smoothing out the 5-foot-10, 175-pound Callison’s left-handed swing and getting him to hit to left field. Mauch also encouraged the speedy Callison to occasionally drag bunt as a way to sharpen his batting eye and upset the defense. By 1961 Callison was showing signs of brilliance. One-third of his hits that season went for extra bases, including ten triples, the first of five consecutive years in which he reached double figures in that category. He led the league in triples with 16 in 1965. His 84 three-baggers for the Phillies rank him sixth in the team’s all-time list through 2012. He also ranked 12th in doubles and 12th in home runs in Phillies history.

Mauch tried Callison in left field but that didn’t make the best use of his great throwing arm. Beginning in 1962, Callison became the Phillies’ regular right fielder, quickly mastering the tricky bounces off Connie Mack Stadium’s 34-foot-high wall. From 1962 through 1965, Callison led all right fielders in the majors with 90 assists – quite a feat when you consider that the great Roberto Clemente, possessor of one of the strongest arms in the major leagues at the time, had 59.

The 1962 campaign proved Callison’s breakthrough season. He hit .300 for the first and only time in his career – Mauch benched him on the last day of the season to keep his average over the .300 mark. Callison hit 23 homers, tying the record for the most home runs by a Phillies left-handed hitter since the right-field wall in Connie Mack Stadium was raised in height. Then he broke that mark in each of the next three seasons. His 32 home runs in 1965 were the most for any left-hander in the history of Connie Mack Stadium. The 34-foot-high right-field wall probably cost the pull-hitting Callison a number of homers during his ten years with the Phillies.

Arguably, Callison’s greatest season came in 1964, the ill-fated season when the Phillies blew a 6½-game lead with 12 games to play and lost the pennant. Playing in all 162 games, Callison hit .274, scored 101 runs, and drove in 104 while banging out 31 homers. He won the All-Star Game with a dramatic ninth-inning, three-run homer off Dick Radatz. That home run became Callison’s most enduring memory. He said he was asked about that feat so many times that he felt like Bill Murray in the film Groundhog Day.4

During the Phillies’ ten-game losing streak, Callison, along with rookie sensation Dick Allen, was one of the few Phillies players to hold his own, hitting .275 with four home runs. Unlike some others, Callison didn’t blame Mauch for the team’s late-season collapse: “It wasn’t all Gene’s fault. We played!”5

Callison probably would have won the Most Valuable Player Award that season but for the Phillies’ pennant collapse. As it was, he finished second to Ken Boyer of the St. Louis Cardinals.

Callison twice hit three home runs in a game for the Phillies, the first against the Milwaukee Braves during the ten-game losing streak in 1964. The second time came a year later, June 6, 1965, against the Chicago Cubs.

Callison had another solid year for the Phillies in 1965, hitting 32 homers and driving in 101 runs. Then, beginning in 1966, his power numbers dropped precipitously. He hit just 11 home runs in 1966 and never hit more than 20 again. Beginning in 1966, Callison’s power numbers continued to decline. His slugging percentage reached a peak of .509 in 1965, but dropped over 100 points two years later.

At 27, Callison effectively was finished as a major-league power hitter. What happened to him isn’t clear. He claimed he suffered a number of nagging injuries – to his legs in particular – that destroyed his ability to play. In 1966 he complained of problems with his eyes. He tried wearing glasses and even adopted a vigorous exercise program that Carl Yastrzemski said benefited his own career. But nothing worked. In baseball circles it was believed that Callison had lost his self-confidence. Even at the height of his success in 1964, Callison had admitted that he was “the biggest worrier around” in an article in Sport magazine.6

After three more undistinguished years with the Phillies, Callison was traded to the Chicago Cubs after the 1969 season with pitcher Larry Colton for pitcher Dick Selma and outfielder Oscar Gamble. He loved playing with Cubs but couldn’t stand manager Leo Durocher, whom he blamed for some of his troubles, claiming that Durocher almost drove him out of baseball.7 Callison stayed with the Cubs for two seasons but clashed with Durocher over playing time. In July 1970, while Callison was in the midst of a good season, he wrote that Durocher “got a wild hair up his ass” and began platooning him. Callison found sitting on the bench “torture.”8 Despite playing in 147 games in the season, Callison got to bat only 477 times, an indication that Durocher was pinch-hitting for him at times. That was Callison’s last decent season; he hit.264 with 19 home runs while driving in 68 runs. After the 1971 season, he was traded to the New York Yankees, and he finished his career there in 1973.

After retiring, Callison worked in a variety of jobs including car salesman and bartender, none of which suited his talents. He longed to get back into baseball in some capacity but never found a place. For years he attended the Phillies’ fantasy camps in Florida, where he was popular with both the fantasy players and his former teammates.

Callison married his high-school sweetheart, Dianne Hammitt, while still in school. Along with their three daughters, Lori, Cindy, and Sherri, they resided for years in Glenside, a small town outside Philadelphia.

Callison’s health was poor after his retirement from baseball. He suffered from a serious case of ulcers, experienced a heart attack, and eventually died from cancer on October 12, 2006, at the age of 67.

Despite the decline of his careers with the Phillies after the 1965 season, Callison still has a significant place in the team’s records. Through 2012 he was among the top ten Phillies in games played in the outfield, triples, and extra-base hits. For five years, from 1962 through 1966, he was the idol of the city and easily the most popular player on the team. All in all, not a bad record to leave.

This biography is included in “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. An earlier version originally appeared in SABR’s “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda.

Sources

Bostrom, Don. “Johnny Callison’s Most Memorable Moment,” home.onemain.com.

Callison, John Wesley, with John Austin Sletten. The Johnny Callison Story (New York: Vantage Press, 1991).

Hochman, Stan. “The Survivors of ‘64’: Johnny Callison,” in Richard Orodenker, The Phillies Reader (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996).

Rossi, John P. The 1964 Phillies: The Story of Baseball’s Most Memorable Collapse (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005).

Westcott, Rich and Frank Bilovsky, The New Phillies Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993).

Westcott, Rich. Philadelphia’s Old Ballparks (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996).

Notes

1 John Wesley Callison with John Austin Sletten. The Johnny Callison Story (New York: Vantage Press, 1991), 10.

2 Ibid.

3 Rich Westcott and Frank Bilovsky, The New Phillies Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993).

4 Don Bostrom, “Johnny Callison’s Most Memorable Moment,” home.onemain.com.

5 Stan Hochman. “The Survivors of ‘64’: Johnny Callison,” in Richard Orodenker, The Phillies Reader (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 172.

6 Johnny Callison, “I’m the Biggest Worrier Around,” Sport, July 1965.

7 Hochman, 175

8 Callison with Sletten, 182.

Full Name

John Wesley Callison

Born

March 12, 1939 at Qualls, OK (USA)

Died

October 12, 2006 at Abington, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.