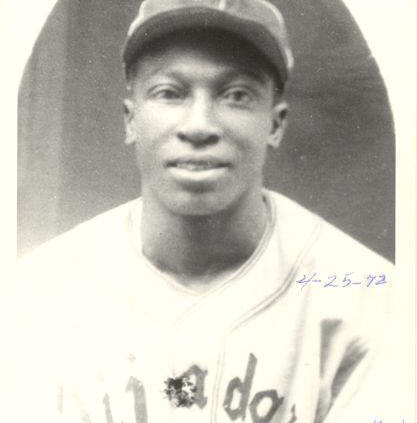

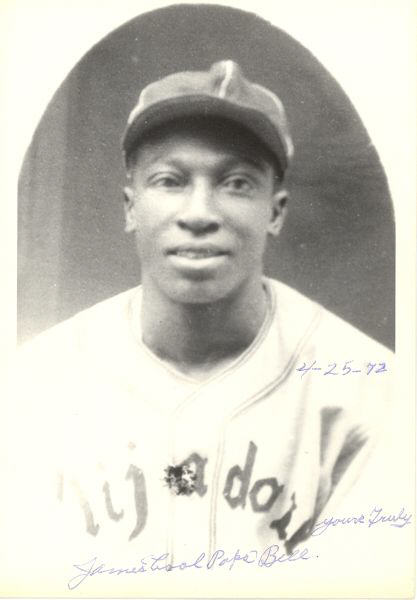

Cool Papa Bell

“He was a beautiful person. Yes he was. Cool Papa Bell. He was a lovable person. And still is. And always has been. I love him. My goodness, that’s one beautiful man.” – Dave Barnhill (hard-throwing ace pitcher and all-star of the New York Cubans)1

“He had time for everybody. Never hurried. Signed autographs, talked to the people, gave advice on baseball, anything they wanted. All the time showing his big beautiful smile. He was so kind. If everybody was like Cool, this would be a better world.” – Judy Johnson (Hall of Fame third baseman)2

He was often described as regal, noble, gentle, and soft-spoken, and a person would be hard pressed to find an ill word uttered about Negro League legend Cool Papa Bell. Just the mention of his name conjures up a seemingly endless line of mythical stories, some true and some no doubt exaggerated. Bell played for three of the greatest teams in Negro League history, the St. Louis Stars of 1928-1931, the Pittsburgh Crawfords of 1932-1936, and the Homestead Grays of 1943-1945. He played in eight East-West All-Star games, was enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in 1974, and is often mentioned as the fastest baseball player ever to lace up a pair of spikes.

He was often described as regal, noble, gentle, and soft-spoken, and a person would be hard pressed to find an ill word uttered about Negro League legend Cool Papa Bell. Just the mention of his name conjures up a seemingly endless line of mythical stories, some true and some no doubt exaggerated. Bell played for three of the greatest teams in Negro League history, the St. Louis Stars of 1928-1931, the Pittsburgh Crawfords of 1932-1936, and the Homestead Grays of 1943-1945. He played in eight East-West All-Star games, was enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in 1974, and is often mentioned as the fastest baseball player ever to lace up a pair of spikes.

James Thomas Nichols was born just outside of Starkville, Mississippi, on May 17, 1903. His mother, Mary Nichols, was widowed before his birth when Samuel Nichols died just a month after they were married. Bell had six brothers and two sisters.3 He claimed that his grandfather was three-quarters Indian and his great-grandfather was full-blooded Indian, although he didn’t know which tribe they were from.4 Mary was remarried some time after James was born to a man named Jonas Bell. James didn’t take on his stepfather’s name until he was forced to do so after his move to St. Louis in 1920. As he recalled, “They said you got to have your father’s name. Just changed my name to Bell.”5

James spent the majority of his childhood helping out on his grandfather’s farm, on which the family raised cotton, corn, fruit, vegetables, and just about anything else that people had a use for.6 He also began to play baseball on those hot summer days in rural Mississippi and later recalled playing ball at the age of 10 as one of his fondest memories:

“I was just a little boy, but I could throw hard. One day there was a picnic in a little town called Blackjack. After we ate under the cool shade trees, they asked me to pitch in the men’s game. I was scared, but I went out and did my best. I pitched three innings and struck out eight of the nine men I faced. The only guy who hit the ball was Joe Minor. He was the best hitter around, a big guy with thick wrists and real strong forearms. But all he could do was hit a little grounder back to me.

“When it was my turn to hit, a big woman came running to the plate, picked me up, and put me on her shoulder. She yelled at the pitcher, ‘You’re throwing too fast, and this little boy’s going to get hurt.’ But they convinced her to let me bat, and, on the first pitch, I hit a line drive into the outfield for a single. I stole second base and wound up scoring the winning run in the game. Was I happy!

“After I left the field the girls came running up to me and gave me a big piece of chocolate cake. I remember that game better than any I played as a professional.”7

Bell moved north to St. Louis at the age of 17 to live with his brothers and (perhaps) stepbrothers, Robert, Fred, L.Q., and Sammy.8 It is not known which siblings were fathered by Samuel Nichols and which by Jonas Bell, although James claimed that he was raised without a father. He got a job at a packing house and had hoped to go to night school, but the lure of baseball was just too strong.9 He started playing sandlot ball on the weekends with the Compton Hill Cubs. Bell’s first known appearance in a game was mentioned in a short write-up in the October 15, 1920, edition of the St. Louis Argus. The game took place on October 10, against the East St. Louis Cubs, and Bell was listed as the pitcher — with his older brother Robert catching — in a 15-4 victory for the Cubs.10

In the spring of 1922 those same East St. Louis Cubs were looking for a pitcher to go up against the Negro National League’s St. Louis Stars. Bell jumped at the chance. Although he lost that contest, 9-1, on Sunday, April 30, he struck out eight and impressed the Stars so much that they immediately signed the 19-year-old for $90 a month and headed out on a long road trip with Bell in tow.11

Bell’s first Negro League appearance most likely took place on May 9, 1922, against the Indianapolis ABCs as a lanky knuckleball pitcher.12 In regard to his pitching, Bell said, “I used to throw the knuckle ball. If I got two strikes on you, I could throw my knuckle ball and it would just do this dart-down. I bet you I could strike anybody out with that knuckle ball. My brother couldn’t catch me. But you know who could catch me with that knuckle ball? My sister.”13

It was around this time that Bell received his legendary moniker. Big Bill Gatewood, manager of the Stars in 1922, who had twirled the Negro Leagues’ first no-hitter during the previous season, is most often credited with bestowing the fabled “Cool Papa” nickname upon Bell.14 Supposedly, Bell fanned Oscar Charleston during a tight spot in an early-season game and Gatewood commented about how cool under pressure he was. Papa was added later to make it sound better.15 Gatewood’s influence on Cool Papa’s career didn’t stop there. He also had the foresight to move Bell to the outfield to get his bat in the lineup more often, and persuaded him to bat left-handed to take advantage of his speed heading to first.16 Bell switch-hit for the remainder of his career.

Negro Leagues pioneer Rube Foster was so impressed with Bell’s speed that he issued him a challenge. Wanting to see how fast Cool Papa truly was, he pitted Bell against Jimmy Lyon, the league’s fastest player at the time. Bell won the race easily. Afterward, Foster remarked on Bell’s cheap shoes:

“ ‘If you can run that well in those shoes, just think what you might do in a good pair. Tell you what, go down to the Spalding Sporting Goods Store here in Chicago and tell the man you want the best pair of spikes he has in stock. Charge them to me.’ I thanked him and told him I’d get the shoes, but I was going to pay him back. I was raised to pay my debts. The man at the store gave me a pair of kangaroo-hide shoes. They cost $21, but by the end of the season, I had saved enough to pay Mr. Foster back.”17

Bell continued to pitch for the Stars in 1922 and posted a 7-7 record as he completed nine of his 12 starts and spun one shutout. He fared better in 1923, going 11-7 and completing nine of 14 games started in a total of 25 appearances. However, the team ranked near the bottom of the league in both seasons.18

The California Winter League was the first professional circuit to pit Negro League teams against squads of white professionals. The league began play at the turn of the twentieth century and its season ran between October and February until the league disbanded after the 1947 campaign. Cool Papa was a fixture in the league and played 12 seasons out West. His first go-around in California came after his rookie season with the Stars in 1922-1923. According to Bell:

“I went to California that winter on the pitching staff to play in the winter league. We got rooms in a little hotel down by the station, a big room, had two beds. My brother Fred Bell and I slept in one. Turkey Stearnes slept in the other. … (Stearnes) went to Cuba and they needed an outfielder, so they put me out there. One Saturday we were playing in Pasadena and a lot of balls were hit over the center fielder’s head. I’d run over behind him and catch them. So from then on I played center field. I wasn’t a pitcher anymore.”19

Bell split his time between playing center field and pitching for the Stars in 1924. He batted .289 in 246 at-bats and went 3-1 on the mound, but Bell and the St. Louis Stars did not really hit their stride until 1925.20

Between 1925 and 1927 Bell’s batting average never dipped below .316, including a stellar 1925 campaign in which he batted .342 in 409 at-bats with 99 runs scored. Of course, these are only the partial numbers that historians have been able to unearth so far; his actual statistics were likely much higher. The St. Louis Stars were 180-103 during this period for a .636 winning percentage, and, with the addition of Hall of Famer and powerhouse slugger Mule Suttles in 1927, the best was yet to come.

Bell met his wife, Clara, at some point in the late 1920s, but there initially was a slight roadblock to their union. Bell’s best friend and roommate, future Hall of Fame shortstop Willie Wells, was courting Clara at the time, but Wells’s mother disapproved of the relationship, which gave Bell the opportunity to swoop in. This turn of events did not affect the two players’ friendship; Bell and Wells remained close for the remainder of their lives.21 Willie Wells summed up the situation and their relationship when he said:

“Cool Papa Bell was my best friend in St. Louis. He was the most beautiful ballplayer and a great base runner. And Bell was a clean liver, he wouldn’t dissipate at all. He was like me. We’d sit in the room and play cards, he and I. We were roommates. He married a girl who was my sweetheart. But he and I were just like this-friends-you know? It never came between us. A good relationship. A wonderful fellow. Bell, he was a beaut.”22

Cool Papa and Clara were married in 1928 and they went on their honeymoon to Cuba, where Bell got his first taste of life and baseball in Latin America.23

Bell enjoyed tremendous success in the Cuban Winter League. In the 1928-29 season he led the league with 44 runs scored, 5 home runs, and 17 stolen bases. He hit a robust .325 while playing for the Cienfuegos Elefantes.24 The following season saw more of the same as Bell once again led the league with 52 runs and became the first player in Cuban League history to hit three home runs in game when he stroked three inside-the-park four-baggers in a game played on New Year’s Day in 1929.25

The St. Louis Stars started firing on all cylinders in 1928 as Bell, along with Mule Suttles and Willie Wells, led their team to a 65-26 record and a nine-game championship series victory over the Chicago American Giants, including wins in Games Eight and Nine as they faced elimination. Bell hit a solid .336 during the season and turned it up a notch for the championship series, in which he rapped out 11 hits in 27 at-bats (.407).26

The Stars continued their successful run into the early 1930s. The team captured the Negro National League championship in 1930, with a seven-game win over Turkey Stearnes and his Detroit Stars, and repeated as uncontested champions in 1931, a season in which the squad won both the first- and second-half NNL titles. Bell was outstanding during the 1930 campaign: He hit .350 and scored 109 runs in only 366 at-bats and led his team to a sparkling 73-28 record, 13½ games ahead of the second-place Kansas City Monarchs.

The Negro National League fell victim to the Great Depression and disbanded after the 1931 season. The demise of the first NNL also marked the downfall of one of the greatest teams in Negro League history, the St. Louis Stars. Bell spent 1932 bouncing around between the Independent League Kansas City Monarchs and the Detroit Wolves and Homestead Grays of the East-West League before finally settling in with the storied Pittsburgh Crawfords amid the return of the Negro National League in 1933.27

Bell was often called the black Ty Cobb and was also compared to other players, like Wee Willie Keeler, who chopped down at the ball and relied on their speed to beat opponents. Bell said as much as he explained, “I’d stand back from the plate and chop down on the ball. That’s something I learned from the old players. By the time the ball comes down, they can’t throw me out. They’d bring in their infield, as if there was a man on third and no out; they couldn’t get me if they played back in their normal position. I’d just hit the ball to short, and if he has to move over for it, he can’t throw me out.”28 Hall of Fame third baseman Judy Johnson put it this way: “He was so fast, that if he hit a ground ball to the left side of the infield that took more than one hop, you just couldn’t throw him out. Might just as well hold the ball.”29

Gus Greenlee, racketeer and owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, began to load up on talent for the 1933 season. He had already signed Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige, the best hitter and pitcher available, and soon set his sights on Cool Papa Bell, the fastest player in the Negro Leagues. “Greenlee told me that I had the chance to be part of the best team in the history of black baseball and that I was the key,” Bell remembered.30 Greenlee’s boast may not have been exaggeration as the 1933 Pittsburgh Crawfords featured five future Hall of Famers in Bell, Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Paige, and Judy Johnson. Bell appreciated what Greenlee was trying to do with the Crawfords: “Gus really did his best to run a class organization. We had a fine bus, nice uniforms, good equipment, everything.”31

One of Bell’s signature achievements is said to have taken place during the 1933 season. Although the claim cannot be supported by currently available statistics, it is something that Bell consistently claimed to be true throughout his lifetime. He asserted, “The best year I ever had on the bases was 1933. I stole one hundred and seventy-five in about one hundred and eighty to two hundred ball games, all of them against other Negro League teams.”32 Bell also kept track of Gibson’s mammoth blasts during his stint with the Crawfords: “People ask me how many homers Josh Gibson hit and I can’t tell them for sure. I did count 72 in 1933. Josh and I played on the Crawfords from 1933 to 1936, and I can tell you that during those seasons he never hit less than 60 home runs and maybe as many as 80 or 85.”33 Such assertions may appear to be tall tales, but, unlike Satchel Paige’s legendary hyperbole, Bell was a thoughtful, straightforward man, whose intelligence and honesty make these legends more likely.

The East-West All-Star Game, which became the centerpiece of every Negro League season, took place for the first time in 1933. The creation of sportswriters Roy Sparrow of the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph and Bill Nunn of the Pittsburgh Courier, they took their idea for the game to the man who could make it happen: Gus Greenlee. This annual contest was even more popular than the Negro League World Series and was an event the players excitedly looked forward to each year.34 Players were selected by the fans through the prominent black newspapers of the day. Bell had already logged 11 seasons before the inaugural game was played, but he still managed to play in eight East-West games. While he did not have much success in these contests, with only six hits in 30 at-bats, he produced a defining moment in the 1934 game.35 Bell walked in the eighth, stole second, and then scored the only run of the game when he sprinted home from second on a bloop single to give the East a 1-0 victory.36

The 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords were a juggernaut, and the team is often compared to the 1927 New York Yankees. The Crawfords were a force of nature and rank among the greatest teams to ever take the field.37 Sporting a 50-23-3 record, the Crawfords ran away with the first half of the Negro National League season and featured a star player at almost every position. In 49 recorded games, Bell scored an amazing 68 runs and batted .345 in the process. The Crawfords faced Hall of Famer Martin Dihigo and his New York Cubans in the NNL Championship Series in which Bell celebrated another career-defining moment. A back-and-forth series led to a Game Seven that the Cubans led 8-5 in the eighth inning. The Craws mounted a comeback against Luis Tiant Sr. as homers by Gibson and Charleston tied it up before Bell worked his magic. He singled off Dihigo, who had replaced Tiant on the mound, stole second, and then raced home with the winning run on a bobbled infield grounder.38 For the second time in three years — the team had also won the title in 1933 — the Pittsburgh Crawfords were champions of the Negro National League.

The Crawfords remained a formidable team in 1936 and again captured the NNL championship, but cracks were beginning to show. By the spring of 1937, Gibson had been traded to the Homestead Grays and Bell, Paige, and Sam Bankhead had all left to play in the Dominican Republic and had cited low pay in the Negro Leagues as the reason for jumping their contracts.39 The mighty Pittsburgh Crawfords hung it up for good after the 1938 season, with the remnants of the team moving to Toledo in 1939 and then Indianapolis in 1940 before finally disbanding. A wistful Cool Papa Bell looked back on his four years with the team. “We had such a great team, a team that could win in every way possible. I was sorry I had to leave the Crawfords.”40

Instead of playing in the Negro Leagues in 1937, many Negro League stars made the jump to the Dominican Republic in search of a better payday. Satchel Paige helped lure teammates Bell, Josh Gibson, Sam Bankhead, and Chester Williams south of the border to play for dictator Rafael Trujillo’s team in Ciudad Trujillo to help boost his chance for re-election.41 The players quickly realized the predicament they’d gotten themselves into. Bell asked a local resident, “They don’t kill people over baseball, do they?” The man responded. “Down here they do.”42 Luckily for Bell and company, they won the championship game, albeit under very tense circumstances. In the bottom of the seventh, with his team trailing 3-2 and two out, Bell singled and Sam Bankhead homered to give Trujillo a 4-3 lead. Paige retired the final six batters in a row and they escaped with the win. They couldn’t get out of town fast enough.43

The most improbable of the Cool Papa Bell yarns turns out to be the one that’s verifiably true. For over 40 years, Satchel Paige claimed that “Bell was so fast he could flip the switch and then jump in bed before the light went out.”44 At a 1981 Negro League reunion in Ashland, Kentucky, Bell came clean about this story:

“During one winter season in the late 1930’s, Satchel and I roomed together out in California. One night, before he got back, I turned off the light, but it didn’t go out right away. There was a delay of about three seconds between the time I flipped the switch and the time the light went out. There must have been a short or something. I thought to myself, here’s a chance to fool ol’ Satch. He was always playing tricks on everybody else, you know. Anyway, when he came back, I said, ‘Hey, Satch, I’m pretty fast, right?’ ‘You’re the fastest,’ he said. ‘Well,’ I said, ‘you haven’t seen anything yet. Why, I’m so fast, I can turn out the light and be in bed before the room gets dark.’ ‘Sure, Cool. Sure you can,’ he said. I told him to sit down and watch. I turned off the light, jumped in bed, and pulled the covers up to my chin. Then the lights went out. I howled and Satchel was speechless for once. Anyway, he’s been telling the truth all these years.”45

Barnstorming against teams made up of white major leaguers was common during the offseason, and Bell was a staple in these contests as well. He is credited with a .311 lifetime batting average in 52 of these exhibitions, with 57 hits and 21 stolen bases, and, like the teams he played for, often dominated squads made up of his white counterparts.46 In a 1931 game in St. Louis, against a team that included future Hall of Famers Max Carey, Paul Waner, Lloyd Waner, and Charlie Gehringer, the Negro Leaguers embarrassed the white team, 18-3. Bell ran wild in the game as he bunted for a hit his first time up, then stole second, third, and home against New York Giants pitcher Bill Walker. The display of daring and speed prompted Detroit Tigers great Charlie Gehringer to remark, “I saw Ty Cobb many times, even as a young man before I joined the Tigers. But I never saw him do anything like Bell did in St. Louis that night.”47

The Negro League players played a different style of baseball than the white major leaguers of the time, which is what often gave them the advantage. Bell called it tricky baseball and explained:

“When I came up, we didn’t play baseball like they play in the major leagues. We played tricky baseball. When we played the big leaguers after the regular season, our pitchers would curve the ball on 3-2. They’d say, what, are you trying to make us look bad? We’d bunt and run and they’d say, why are you trying to do that in the first inning? When we were supposed to bunt, they’d come in and we’d hit away. We’d go into third standing up so the third baseman couldn’t see the throw coming and it might go through him. The major leaguers would play for one big inning. I think we had a better system than the majors. Whatever it takes to win, we did.”48

In addition to the offseason barnstorming tours, Bell continued to play ball in the Latin winter leagues. Bell and many other Negro League players loved life so much in Latin America that they did not want to leave. Bell said of his time in Latin America, “Everybody was the same down there. We could go in any restaurant, stay in hotels, and oh, the fans? They loved us.”49 Life in Latin America provided a stark contrast to the way Negro League players were treated under Jim Crow laws in the States. Bell played exclusively in the Mexican League from 1938 to 1941, and put his Negro Leagues career on hiatus.

As a former knuckleball pitcher, Bell was able to help his good friend Satchel Paige learn a new pitch while the two were in Mexico. Bell recounted, “In 1938 his arm got sore and I told him, see Satchel, you’ve got to learn to pitch. I showed him how to throw the knuckle ball, and he was throwing it better than I was. That’s what I liked about him, he didn’t want anybody to beat him doing anything.”50

Bell was a superstar in the Mexican League, where he had some of his finest seasons. Perhaps no season was finer than his 1940 campaign with Vera Cruz during which he captured the league’s triple crown and led the team to a championship. Bell hit an astounding .437 with 12 home runs and 79 RBIs in 89 games. He also showed off his speed with 15 triples and a remarkable 119 runs scored. Bell’s four years in Mexico saw him hit .367 overall, and he scored 310 runs in 287 games.51

Bell is obviously most famous for his speed. When Negro League legend, manager, and historian Buck O’Neil was asked, “Just how fast was Cool Papa Bell?,” he would always answer the same. “Faster than that.”52 One of Bell’s most famous quotes about circling the bases in 12 seconds flat cannot be verified, but a recorded time of 13.60 was reported by the Los Angeles Times in 1933, and Bell claims he did it on a wet field. A time of 13.60 puts him slightly behind Maury Wills and ahead of Ty Cobb in recorded times circling the bases.53 Jesse Owens famously dodged Bell when Owens traveled with different teams and took on all comers.54 In 1933 Hall of Fame Pittsburgh Pirate great Paul Waner complimented Bell: “The fastest man I have ever seen on the baseball diamond was Cool Papa.”55

Former Negro League and major-league star and Hall of Famer Monte Irvin also extolled Bell’s ability:

“He might’ve been the fastest baseball player who ever lived. They used to tell stories about Bell’s running. He was known to score from second base on a bunt. That’s right. Now, suppose he’d played under good conditions, you know, get a massage after every game, not have to drive five hundred miles to play a doubleheader, this kind of thing. There’s no telling how many bases he would’ve stolen. It’s just a shame that more people didn’t get to see him. The only comparison I can give is, suppose Willie Mays had never had a chance to play big league. Then I were to come to you and try to tell you about Willie Mays. Now this is the way it is with Cool Papa Bell.” 56

Although Bell is best known for his feats on the basepaths, he was no slouch in the field, a fact to which Satchel Paige attested in his autobiography: “Why, he was the best fielder you ever saw. He could grab that ball no matter where it was hit. He was just like a suction cup.”57 Paul Waner agreed when he called Bell “the smoothest center fielder I’ve seen.”58 Trailblazing owner Bill Veeck compared him to center fielders Willie Mays, Joe DiMaggio, and Tris Speaker and called Bell “one of the most magical players I’ve ever seen.” And Hall of Famer Pie Traynor once remarked, “It doesn’t matter where he plays. He can go a country mile for a ball.”59

Bell returned from Mexico to the Negro Leagues for a short stint with the Chicago American Giants in 1942 before he signed on with the Homestead Grays the following year. Bell had a knack for playing on great teams, and the 1943 Grays were an overwhelming force that finished the year with a 78-23-1 record and captured their fourth straight NNL title. The 40-year-old Bell led off, played left field, and had a hand in helping the Grays win their first Negro League World Series title by beating the Birmingham Black Barons in a nailbiter, four games to three.60 Bell hit a game-winning single in the bottom of the 11th inning to take Game Three, 4-3, and had a solid Series in which he went 8-for-26 for a .308 average.61

Bell found a kindred spirit on the Grays for the 1944 season in aging veteran and fellow Hall of Famer Buck Leonard. The two intelligent, soft-spoken men were perfect roommates, who both preferred to forgo the nightlife and retire early every evening; however, they were not above taking a couple swigs of gin before bedtime to help with their arthritis. Pittsburgh Courier columnist Wendell Smith said of the duo, “These men weren’t big drinkers; they were aging ballplayers trying to stall Father Time.”62

The Homestead Grays once again met the Birmingham Black Barons in the 1944 Negro League World Series and this time dismantled them, four games to one. The 41-year-old Bell stroked .322 for the season and chipped in with a respectable .260 in the Series.

The 1944-1945 offseason marked Bell’s last campaign in the California Winter League. His success in this league rivaled that of his Mexican League accomplishments as he finished with a .368 batting average in 159 games, including 219 hits in 596 at-bats, with 16 homers, 12 triples, and 31 doubles in 12 years of action. He won two batting titles and his teams consistently dominated the league in each season that he played.63

Bell began to feel all of his 42 years in 1945 with the Homestead Grays. He recalled, “In ’45 I was sick. I had arthritis, I was stiff, I couldn’t run.”64 He still managed to hit .299 and helped the Grays to a 47-25-3 record and yet another NNL title, their sixth in a row. The Grays ran into a buzz saw in the World Series, though, and were swept by the Sam Jethroe-led Cleveland Buckeyes in four games. The aging Grays managed only three runs in the Series and hit a paltry .165.

The 1946 Homestead Grays failed to win the title, but Bell amazed everyone by leading the batting race near the end of the season. Soon, he performed one of his most selfless acts as he ceded the title to Monte Irvin. Bell explained his motives thusly: “For the first time the Major Leagues were serious about taking in blacks. I was too old, but Monte was young and had a chance for a future. It was important he be noticed, important he get that chance.” Bell removed himself from the lineup and ended up not having enough at-bats to qualify for the title.65 He still ended up hitting .393 in his final season in the Negro Leagues.

Soon after Bell’s retirement, he signed on to manage the Monarch Travelers, an independent team that played west of Kansas City in search of major-league talent. Bell managed this team through 1949 and turned out to be adept at recognizing future stars.66 He is credited with first spotting Cubs Hall of Fame shortstop Ernie Banks and recommending him to Buck O’Neil and the Kansas City Monarchs.67

With major-league integration just around the corner, it was difficult for players like Bell not to wonder what might have been. Had integration come sooner, fans could have witnessed the greatness of players like Bell, Gibson, Charleston, Leonard, Johnson, and Suttles in their primes. They would be household names like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Ty Cobb. For more than a decade before Jackie Robinson was signed, the hope that the color barrier might be broken seemed tantalizingly close. Bell had the final word on this false hope: “They used to say, if we find a good black player, we’ll sign him. They was lying.”68

Cool Papa Bell played a role in Jackie Robinson’s success at integrating the major leagues. News that Robinson was about to sign with the Dodgers had many veterans worried that he might not make it. Bell told of the players’ outlook and his role:

“All us old fellas didn’t think he could make it at short. He couldn’t go to his right too good. We was worried. He miss this chance, and who knows when we’d get another chance. So I made up my mind to show him he should try for another spot in the infield. One night I must’ve knocked a couple hundred ground balls to his right, and I beat the throw to first every time. Jackie smiled. He got the message. He played a lot of games in the majors, only one of ’em at short.”69

Bell produced another highlight in 1948 when Satchel Paige got him to suit up against a team led by future Hall of Famer Bob Lemon and, ironically, Jackie Robinson. 70

Bell also described his iconic moment:

“So this time I was hitting eighth and I got on base, and Satchel came up and sacrificed me to second. Well, Bob Lemon came off the mound to field it and I saw that third base was open, because the third baseman had also charged in to field it. Roy Partee, the catcher, saw me going to third, so he went down the line to cover third and I just came on home past him. Partee called ‘Time, time!’ But the umpire said, ‘I can’t call time, the ball’s still in play,’ so I scored.”71

Cool Papa Bell finally hung up his spikes for good in 1950 and moved back to St. Louis with his wife, Clara, where he took a job working for the city, first as a custodian and later as a night watchman.72 Bell sometimes took in Cardinals games and on a couple of occasions shared his wisdom and experience with the stars of the day. The Dodgers asked him to help out young speedster Maury Wills. Bell did, and advised Wills, “When you’re on base get those hitters of yours to stand deep in the box. That way the catcher, he got to back up. That way you goin’ to get an extra step all the time.”73 Wills went on to steal 104 bases not long after that. Cardinals speed demon Lou Brock also listened and learned when Bell was around. Brock recalled, “He was a nice man, a good teacher, and he just instinctively knew more about stealing a base than anyone else I’ve ever met.”74

St. Louis Browns owner Bill Veeck made an attempt to sign both Bell and Buck Leonard in 1951, but both players were well past their primes. A 48-year-old Bell explained his decision not to play: “People told me I should have tried for the job just for the money, but I couldn’t do it just for a paycheck. I never had any money, so I never worried about it. I just didn’t want fans to boo me, and if I had played at that age they sure would have. Sometimes pride is more important than money.”75

Bell and Clara continued to live in their small St. Louis apartment, which was surrounded by abandoned stores and vacant lots. Bell worked for nine years as a city hall custodian and spent another 13 years as the night watchman on the midnight-to-8 shift. His 22 years with the city earned him a paltry $130-a-month pension.76

In the meantime, Bell had to wait until 1974 to finally get the call every ballplayer dreams of. Cool Papa Bell was unanimously voted into baseball’s Hall of Fame in Cooperstown and was inducted on August 12, 1974. He was the fifth Negro Leaguer to be elected and joined Paige, Leonard, Gibson, and Irvin in baseball’s hallowed shrine. Bell remained cool when he was given the news. He said, “It’s the highest honor, but I don’t jump up and down and holler and rush to the telephone to call my friends. They’ll learn about it sometime.”77 Ed Stack, former president of the Hall of Fame, said of Bell in 1991, “Cool Papa was the dean of the living Hall of Famers. What he said had a tremendous amount of meaning. It was the sermon of the evening, the inspiration and mood-setting for the whole weekend.”78

Bell made the trip from St. Louis to Cooperstown every year until his health finally prevented him from traveling toward the end of his life. He signed autographs, took pictures, and talked with fans for hours until no one remained. When asked about the dangers of the long journey at his advancing age he responded, “So what if I died on the way to Cooperstown. Besides Clara, baseball has been my whole life.”79

Cool Papa Bell’s beloved wife of 62 years, Clara, died on January 20, 1991. Bell suffered a heart attack shortly thereafter, on February 27, and died at St. Louis University Hospital on March 7.80 The couple was survived by their only daughter, Connie Brooks. Lou Brock was one of Bell’s pallbearers and had this to say after the funeral: “To his grave goes a whole chapter in the black history of baseball, in black history, period. His dream got deferred. I just hope somewhere in history that his performance gets accurately recorded.”81

Bell wasn’t bitter about his exclusion from the major leagues. In 1988, at his home in St. Louis, he reflected on his life.82 In summary of all he had experienced, he said, “Because of baseball, I smelled the rose of life. I wanted to meet interesting people, to travel, and to have nice clothes. Baseball allowed me to do all those things, and most important … it allowed me to become a member of a brotherhood of friendship which will last forever.”83

Sources

All statistics, unless otherwise noted, are from seamheads.com or baseballreference.com.

Notes

1 Jim Bankes, The Pittsburgh Crawfords (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2001), 84.

2 Bankes, 43.

3 Rod Roberts, Cool Papa Bell interview, September 26, 1981, 1. Hall of Fame archives.

4 John Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues (New York: First Da Capo Press Inc., 1992), 112.

5 Rod Roberts interview, 2.

6 Rod Roberts interview, 4.

7 Bankes, 45.

8 Without access to more information, it proved very difficult to determine all family relationships.

9 Mississippi History Now online publication, 1-2008. mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/articles/277/cool-papa-bell.

10 Gary Ashwill, “Cool Papa’s Rookie Season,” Agate Type, July 15, 2016. agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/cool-papa-bell/.

11 Gary Ashwill, “Cool Papa’s Rookie Season.”

12 Gary Ashwill, “How Cool Papa Got His Name,” Agate Type, July 27, 2006. agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2006/07/how_cool_papa_g.html.

13 Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, 113.

14 Leslie A. Heaphy, Black Baseball and Chicago (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2006), 79.

15 Gary Ashwill, “How Cool Papa Got His Name.”

16 Heaphy, Black Baseball and Chicago, 79.

17 Bankes, 47.

18 Seamheads.com seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=bell-01coo.

19 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2002), 88.

20 Seamheads.com. seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=bell-01coo. All statistics are from Seamheads unless otherwise noted.

21 James A. Riley, Dandy, Day, and the Devil (Cocoa, Florida: TK Publishers, 1987), 121.

22 Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, 225.

23 Phil Dixon and Patrick J. Hannigan, The Negro Baseball Leagues: A Photographic History (Mattituck, New York: Amereon House, 1992), 125.

24 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball: 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2003), 348.

25 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season: Pay for Play Outside of the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2007), 42.

26 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, 2001), 237.

27 Baseballreference.com, baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=bell–001coo.

28 Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, 118.

29 Bankes, 44.

30 Mark Whitaker, The Untold Story of Smoketown: The Other Great Black Renaissance (New York: Simon & Schuster Inc., 2018), 109.

31 Larry Lester and Sammy J. Miller, Black Baseball in Pittsburgh (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2001), 35.

32 John Holway, “How to Score from First on a Sacrifice,” American Heritage, August 1970. americanheritage.com/how-score-first-sacrifice.

33 Bankes, 42.

34 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 21-22.

35 Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase, 412-413.

36 Whitaker, The Untold Story of Smoketown, 115.

37 Bankes, 148.

38 Mark Ribowsky, The Power and the Darkness (New York: Simon & Shuster, 1996), 148.

39 Averell “Ace” Smith, The Pitcher and the Dictator (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018), 62.

40 Bankes, 51.

41 Anthony J. Connor, Baseball for the Love of It: Hall of Famers Tell It Like It Was (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. Inc., 1982), 240-241.

42 McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season, 144.

43 William F. McNeil, Baseball’s Other All-Stars (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2000), 172.

44 Bankes, 43.

45 Bankes, 43-44.

46 Todd Peterson, The Negro Leagues Were Major Leagues: Historians Reappraise Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2020), 228.

47 Bankes, 47-48.

48 McNeil, The California Winter League, 111.

49 Patricia C. McKissack and Fredrick McKissack Jr., Black Diamond: The Story of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Scholastic Inc., 1994), 110.

50 Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, 132.

51 Pedro Treto Cisneros, The Mexican League: Comprehensive Player Statistics, 1937-2001 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 2002), 93.

52 “No. 99: Cool Papa Bell,” Medium.com, medium.com/joeblogs/99-cool-papa-bell-ef4d0c4d8bf5.

53 Scott Simkus, Outsider Baseball: The Weird World of Hardball on the Fringe, 1876-1950 (Chicago: Chicago Review Press Inc., 2014), 232-234.

54 Dixon and Hannigan, 214.

55 Dixon and Hannigan, 160.

56 Connor, Baseball for the Love of It, 212.

57 Leroy “Satchel” Paige and David Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (South Orange, New Jersey: Summer Game Books, 2018), 38.

58 William A. Young, J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs: Trailblazers in Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc.,2016), 167.

59 Mark Kram, “No Place in the Shade,” Sports Illustrated, June 20, 1994: 66.

60 Brad Snyder, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003), 162.

61 Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues, 410-411.

62 Snyder, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators, 212.

63 McNeil, The California Winter League, 250.

64 Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, 127.

65 Bill Kirwin, Out of the Shadows: African American Baseball from the Cuban Giants to Jackie Robinson (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2005), 31.

66 Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball (Lawrence: The University Press of Kansas, 1985); 120.

67 Young, J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs, 178.

68 Connor, Baseball for the Love of It, 210.

69 Kram.

70 Timothy M. Gay, Satch, Dizzy & Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson (New York: Simon & Shuster, 2010), 272.

71 Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, 109.

72 Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, 130.

73 Kram.

74 “No. 99: Cool Papa Bell.”

75 Snyder, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators, 292.

76 William Brashler, Josh Gibson: A Life in the Negro Leagues (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2000), 158. See also “Cool Papa Steams Up for Hall of Fame Induction,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, August 9, 1974.

77 “Cool Papa Bell in Hall of Fame,” New York Post, February 13, 1974: 76.

78 “Belated Respect,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, March 17, 1991.

79 Bankes, 139-140.

80 “Cool Papa Dies After Brief Illness,” Sports Collectors Digest, March 29, 1991.

81 “Belated Respect.”

82 Bankes, 83.

83 Shaun McCormack, Cool Papa Bell: Baseball Hall of Famers of the Negro Leagues (New York: Rosen Publishing Group Inc., 2002), 87.

Full Name

James Thomas Bell

Born

May 17, 1903 at Starkville, MS (US)

Died

March 7, 1991 at St. Louis, MO (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.