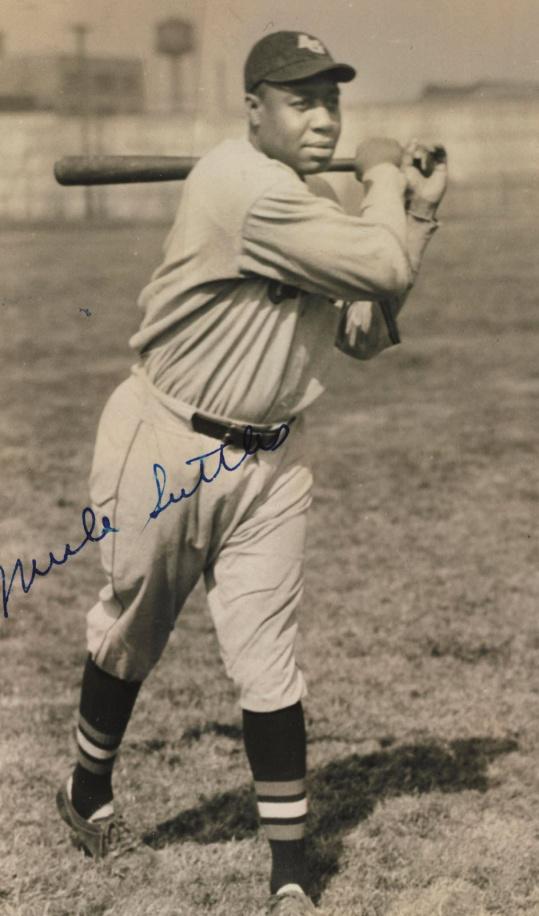

Mule Suttles

George “Mule” Suttles emerged from Alabama coal mines to become one of the greatest power hitters in Negro League history. He drew comparisons to Babe Ruth for his tape-measure home runs, and he hit for average, too; his career batting average is estimated to be .317 by Seamheads.com. The genial first baseman and outfielder was popular and respected by players and fans. When he came to bat, the crowd cheered him with chants of “Kick, Mule, Kick!” In 2006, the slugger was posthumously inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

George “Mule” Suttles emerged from Alabama coal mines to become one of the greatest power hitters in Negro League history. He drew comparisons to Babe Ruth for his tape-measure home runs, and he hit for average, too; his career batting average is estimated to be .317 by Seamheads.com. The genial first baseman and outfielder was popular and respected by players and fans. When he came to bat, the crowd cheered him with chants of “Kick, Mule, Kick!” In 2006, the slugger was posthumously inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

George Suttles was born March 31, 1901, about 40 miles southwest of Birmingham, Alabama, in Blocton, a coal mining boomtown. He was the second of seven children born to James and Early Suttles.1 James was a coal miner, and George worked in the mines as a teenager. Baseball was the “main diversion” in Blocton.2

By 1920, the Suttles family had moved to the Edgewater Coal Mining Camp, 10 miles west of Birmingham,3 and in 1923 George left coal mining to play professional baseball for the Birmingham Black Barons. Playing in left field and batting cleanup on May 28, he contributed two singles, a double, and a home run in the Black Barons’ 16-0 romp over the Nashville Giants at Rickwood Field in Birmingham.4 Box scores incorrectly listed him as “Sellers.”

The Black Barons joined the Negro National League in 1924. Against the Chicago American Giants on June 23, Suttles made a running catch to take a home run from Floyd “Jelly” Gardner.5 At home on September 6, the final day of the Black Barons’ 1924 season, the Birmingham players humorously swapped positions throughout a 9-4 victory over the Atlanta Black Crackers. Suttles began in left field but also pitched and played shortstop, and as reported by the Birmingham News, “the comedy of Mule Sellers [sic]” entertained the crowd.6

In 1925 Suttles moved to first base, and box scores began to spell his name correctly. In the Black Barons’ 7-6 triumph over the ABCs in Indianapolis on May 11, he recorded 14 putouts at first base and delivered at the plate with a home run in the first inning and a game-winning triple in the 10th inning.7

Suttles was a right-handed batter and thrower. He was a big man, about 6’2” and weighing 200 pounds as a young man—close to 250 pounds toward the end of his career. According to one report, he swung an unusually heavy bat, measuring 37 inches and 56 ounces,8 but this may have been an exaggeration; according to Hillerich & Bradsby, Suttles “frequently ordered 36-inch, 36-ounce” Louisville Sluggers.9 With his little finger off the end of the bat,10 he swung so hard “you could feel the earth quake,” said teammate Dick Seay.11

Though a fierce hitter, Suttles was a gentle giant—“the most gentle person I ever saw,” said teammate Lennie Pearson.12 Easygoing and unpretentious, Suttles was “ever-smiling” and “good-natured.”13

In 1926 Suttles joined the St. Louis Stars and teamed with future Hall of Famers Willie Wells and Cool Papa Bell. On June 20, Suttles slugged two home runs, including a grand slam, in the Stars’ 17-2 rout of the Cleveland Elites.14 Sidelined by injury, he missed most of the 1927 season.

The 1928 St. Louis Stars were one of the greatest teams in Negro League history. First-half champions of the Negro National League, the Stars won the postseason championship series, 5 games to 4, over the second-half leaders, the Chicago American Giants. Suttles led the Stars with a .365 batting average that season, according to estimates by Seamheads.com. The team performed in front of enthusiastic crowds at Stars Park in St. Louis. “The per capita lung power of the crowd cannot be challenged by the most exuberant of Sportsman’s Park crowds,” noted the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.15 Sportsman’s Park was home to the major-league Cardinals and Browns.

Suttles played for the St. Louis Stars again in 1929, and he played briefly for the Chicago American Giants in the fall of that year. In the winters before and after the 1929 season, he played in Cuba, where he clouted a legendary home run that traveled more than 500 feet. The ball sailed out of the ballpark and landed in the ocean.

In the spring of 1930, Suttles joined the Baltimore Black Sox and swatted eight home runs in his first four games.16 And on May 20, he smacked a three-run homer in an 11-1 victory over the New York Lincoln Giants; his 23-year-old teammate, Satchel Paige, hurled a four-hitter and struck out 10 in that contest.17

Suttles returned to the St. Louis Stars in June and helped them win their second Negro National League title. He clubbed four home runs in the 1930 championship series against the Detroit Stars,18 which was won by St. Louis, four games to three. There was no championship series the following year; the St. Louis Stars had the best overall record when the league disbanded and were declared champions. The team also disbanded, so in the spring of 1932, Suttles joined the Detroit Wolves of the newly formed East-West League.

On May 14, 1932, Suttles’ walk-off home run in the 14th inning was “a vicious drive over the left centerfield fence” at Hamtramck Stadium and gave the Wolves a 5-4 victory against the Homestead Grays.19 He was traded mid-season to the Washington Pilots and as a member of the Pilots, he belted a 502-foot home run on June 11 at Hilldale Park near Philadelphia.20 From 1933 to 1935, he played for the Chicago American Giants in a reconstituted Negro National League; his teammates included future Hall of Famers Willie Wells, Turkey Stearnes, and Bill Foster.

Suttles’ performances in the annual East-West All-Star Game are especially noteworthy. Two months after the inaugural major-league All-Star Game, the Negro Leagues played the first East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park in Chicago on September 10, 1933. Suttles was a member of the West team that defeated the East squad, 11-7. He hit the only home run in the game, a “scorching” drive into the top tier of the left-centerfield stands in the fourth inning, and he followed it with a “slashing” double to deep right field in the sixth inning.21

The 1934 East-West All-Star Game was a pitchers’ duel at Comiskey Park on August 26. Batting cleanup, Suttles contributed three of the West’s seven hits, but through stellar defense, the East prevailed, 1-0. Suttles tripled to center field in the fourth inning and would have scored on Roy Parnell’s fly ball to deep right field, but Jimmie Crutchfield caught it, whirled and threw a perfect strike to home plate to nab Suttles by a step. Facing Satchel Paige in the sixth inning, Suttles stroked what might have been another hit, but left fielder Vic Harris made a fine running catch near the foul line.22

During the 1935 East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park on August 11, Suttles drew four walks, struck out once, and saved the best for last. Facing the East pitcher, Martin Dihigo, in the bottom of the 11th inning with two men on and two out, he drilled a home run over the right-center-field fence to give the West a thrilling 11-8 triumph. “It was the mighty kick of a mighty ‘Mule,’” wrote sportswriter William G. Nunn, a feat “that fans in years to come will tell their children, their grand-children, and their children’s grand-children about.”23

Though known for his hitting, Suttles also contributed defensively. He was comfortable at first base and in the outfield, and versatile enough to fill in at second base and third base when his team was shorthanded. As a first baseman, he was regarded as a good fielder, though not graceful. He was considered only a fair outfielder, yet he produced some gems. In left field in 1935, he made “two brilliant catches” against the Pittsburgh Crawfords on May 21, and he made a remarkable shoestring catch in the East-West All-Star Game.24

According to records compiled by historian William F. McNeil, Suttles played in 126 games in the California Winter League from 1930 to 1940 and hit .378 with 64 home runs.25 In this league, he played on Negro teams against white competition that included many ballplayers with experience in the major leagues and top minor leagues. In Los Angeles on November 30, 1933, Suttles homered and doubled off Bobo Newsom,26 who won 30 games for the Los Angeles Angels that year and would go on to win 211 major-league games. In Santa Monica on October 27, 1935, Suttles crushed a 475-foot home run off Larry French, one of the ace pitchers of the NL-champion Chicago Cubs.27 Suttles is “big and powerful, [and] takes a healthy cut. When he hits one, it goes long and far,” said AL pitcher Earl Whitehill.28 Suttles hits “towering smashes” like Babe Ruth, said Wally Berger of the Boston Braves.29

In the Negro National League from 1936 to 1940, Suttles played for the Newark Eagles, a club owned by Abe and Effa Manley. Among his teammates were future Hall of Famers Willie Wells, Ray Dandridge, Monte Irvin, and Leon Day. In 1937, the Pittsburgh Courier praised the Eagles’ “Dream Infield” of Suttles at first base, Dick Seay at second base, Wells at shortstop, and Dandridge at third base.30 Suttles and Wells were teammates in 14 consecutive seasons, from 1926 to 1939, until Wells left the Eagles in 1940 to play in Mexico. The laid-back Suttles and the feisty Wells were a study in contrasts.

Suttles was productive for the Eagles from 1936 to 1940, with a .322 batting average, 33 home runs, and 125 RBIs in 136 games according to Seamheads.com. Highlights included a six-RBI game against the Pittsburgh Crawfords on July 17, 1937, and four home runs in a doubleheader against the Homestead Grays on June 4, 1939.31 Nonetheless, the Manleys released Suttles at the age of 40 in the spring of 1941. He played for the New York Black Yankees during the 1941 season.

Both Suttles and Wells returned to the Newark Eagles in 1942—Suttles as a coach of the team and Wells as player-manager. Against the visiting Chicago American Giants on August 16, Suttles filled in at first base and delighted the Newark crowd. In the fourth inning, the big man “put the stands in an uproar” by stealing third base, and in the seventh inning, he used the hidden-ball trick to retire a Chicago baserunner.32

Suttles managed the Eagles in 1943 and 1944. Though his teams had losing records in league play, “he was a tremendous manager,” said Lennie Pearson. “He knew baseball inside and out. … And he had patience. He knew he was in the twilight of his career, and he devoted a lot of time to younger fellows.”33 Among the players Suttles mentored were teenagers Larry Doby and Don Newcombe, who would go on to have successful careers in the major leagues after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. It was the dawn of a new generation of Negro stars. A quarter-century after Suttles debuted with the Birmingham Black Barons, Willie Mays debuted with the Black Barons in 1948.

Suttles managed a Newark bar in 1945 and managed the Newark Buffalos semipro team in 1946.34 He was coach of the New York Black Yankees in 1948, a team that played its home games in Rochester, New York, and he umpired the East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park on August 22, 1948.35 In February 1949, at the age of 47, he married 42-year-old Lucille Childs of Newark.36

It is believed that Suttles spent his remaining years in Newark. At the age of 65, he died of cancer in Newark in July 1966 and was buried at the Glendale Cemetery in Bloomfield, New Jersey. His former teammates were pallbearers. He had told them, “When I die, have a little thought for my memory, but don’t mourn me too much.”37 Lucille died in Evansville, Indiana, in 1991.38

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Joel Barnhart, and fact-checked by Leslie Heaphy.

Sources

Ancestry.com and Seamheads.com (accessed April-May 2019).

Suttles’ file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 1900 and 1910 US Censuses.

2 Charles Edward Adams, Blocton: The History of an Alabama Coal Mining Town (Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2012), 19.

3 1920 US Census.

4 “Black Barons Run Up List of 16 Wins and Two Reverses,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 2, 1923: 7.

5 “Rube’s Giants Win Three from Barons,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 28, 1924: 6.

6 “Rushmen Wind Up Season with Win Over Atlanta, 9-4,” Birmingham (Alabama) News, September 7, 1924.

7 “Birmingham Beats A.s in Ten-Inning Clash,” Indianapolis Star, May 12, 1925: 16.

8 Bennie Caldwell, “Suttles Stocks Up with 6 New Bats as Pilots Prep for Craws Here,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 2, 1932: 15.

9 PJ Shelley, “Kick, Mule, Kick!”, February 7, 2017, Sluggermuseum.com/about-us/blog/article/19/kick-mule-kick.

10 John B. Holway, Black Diamonds: Life in the Negro Leagues from the Men Who Lived It (New York: Stadium Books, 1991), 123.

11 John B. Holway, Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988), 266.

12 Holway, Blackball Stars (1988)., 279.

13 Tommy Deas, “‘Mule’ Gets His Reward,” Tuscaloosa (Alabama) News, July 16, 2006: 1A, 14A; “Springies Seek Revenge from Pilots Tonight,” Long Island (New York) Daily Star, July 20, 1932: 11.

14 “Suttles’ Homer with Bases Loaded Wins Game for Stars, 17-2,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 21, 1926: 18.

15 “St. Louis Negro Nine Tied for World Championship,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 1, 1928: 8.

16 “Black Sox Relying on Suttles’ Bat in Hilldale Contests,” Baltimore Evening Sun, May 1, 1930: 37.

17 “Sox, 11; Lincolns, 1,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 24, 1930: 18.

18 “Another Pennant-Winner,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 29, 1930: 20.

19 “Detroit Wolves Win on Home Run,” Detroit Free Press, May 15, 1932: 41; “Detroit Gets Edge Over Gray,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 21, 1932: 15.

20 “Slams Long Home Run,” Washington Evening Star, June 12, 1932: 4.

21 All-Star Game coverage in Pittsburgh Courier, September 16, 1933: 14, 15.

22 All-Star Game coverage in Pittsburgh Courier, September 1, 1934: 14, 15.

23 All-Star Game coverage in Pittsburgh Courier, August 17, 1935: 8, 15.

24 All-Star Game coverage in Pittsburgh Courier, August 17, 1935: 8, 15.; “Chicago Trims Pittsburgh Foe in Night Battle,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Evening News, May 22, 1935: 10.

25 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002), 261.

26 “Giants Annex Double-header,” Los Angeles Times, December 1, 1933: II-10.

27 “French Loses to Giants, 3-2,” Los Angeles Times, October 28, 1935: II-9.

28 Wendell Smith, “Are Negro Ball Players Good Enough to ‘Crash’ the Majors?” Pittsburgh Courier, August 12, 1939: 16.

29 Holway, Blackball Stars (1988)., 266.

30 “Newark with Wells, Seay and Suttles Has Dream Infield,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 10, 1937: 16.

31 “Pittsburgh Team Set Back by League Foe in Stadium Battle,” Paterson (New Jersey) News, July 19, 1937: 19; “Suttles Hits Three Homers; Eagles Defeat Grays Twice,” Buffalo Evening News, June 5, 1939: 22; “Jim West and Mule Suttles to Vie for First Base Honors in 4-Team Twin Bill Classic,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 24, 1939: 16.

32 “Newark Eagles Beat Chicago 5-3 at Ruppert Stadium,” New York Age, August 22, 1942: 11.

33 Holway, Blackball Stars, 280.

34 David Hinckley, “Suttles Made His Voice Heard,” New York Daily News, February 28, 2001: 62; “Baseball Notes by the Colonel,” Madison (New Jersey) Eagle, May 23, 1946: 14.

35 Scott Pitoniak, “Gem of Local Baseball History Found,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, February 26, 2006: 5D; Frank Mastro, “West Defeats East in Negro Baseball, 3-0,” Chicago Tribune, August 23, 1948: 39.

36 New Jersey Marriage Index, 1901-2016, at Ancestry.com.

37 Holway, Blackball Stars, 280.

38 Indiana Death Certificates, 1899-2011, at Ancestry.com.

Full Name

George Suttles

Born

March 31, 1901 at Blocton, AL (US)

Died

July 9, 1966 at Newark, NJ (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.