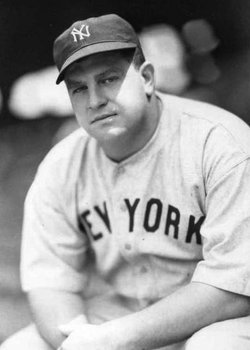

Jumbo Brown

At 6-feet-4, and close to 300 pounds, Jumbo Brown lived up to his name.1

At 6-feet-4, and close to 300 pounds, Jumbo Brown lived up to his name.1

Part of baseball’s first wave of relief pitchers, the massive righty saw action in 249 major-league games, starting just 23. He compiled a 33-31 won-lost record with 28 saves and a 4.07 ERA. The Rhode Island native played with many of baseball’s best. He was with the Yankees when Babe Ruth made his “called shot” in the 1932 World Series; with the Giants during their National League pennant-winning season in 1937; and with Chicago Cubs Hall of Famer Gabby Hartnett when he took the mound in two games for a 3.00 ERA in his major-league debut in 1925 at age 18.

Fluctuating through the years but remaining in the obese range, Brown’s weight has been sourced to his tonsils. After getting them removed in 1927, Brown gained 68 pounds. Working out for five hours a day had no apparent effect.2

Newspapermen often highlighted Brown’s poundage, with labels such as “Walter the Whale,” “Big Brownie,” and “Big Bertha.”3 Even more vivid descriptions included: “jolly Falstaffian flinger,” “turned out on the assembly line at a Ford truck plant,” “Frank Buck brought [him] back alive,” and “athletic Oliver Hardy,”4

Lee Allen, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum historian from 1959 to 1969, also highlighted Brown’s size in his book The Hot Stove League. He told a story, perhaps apocryphal, involving Yankees manager Joe McCarthy:

“‘Why is it you pitch Brown only in Philadelphia?’ McCarthy was asked one day.”

“‘It’s the only way I know to fill Shibe Park,’ Joe quipped.”5

It was not unusual, certainly, for scribes to use weight in depicting Brown’s performance. In January 1939, John Drebinger wrote, “The big fellow, who begins each training campaign by cutting down a displacement of 270 pounds, appeared in 43 games for the Giants last season, pitched 90 innings and compiled the astonishing average of 1.80 earned runs per nine-inning game.”6 Six weeks later, Drebinger noted that Brown’s weight was 256 pounds.7

In March, it happened again: “After weeks of great exertion, Walter is down to a modest 250 pounds. Despite his vast size, he is surprisingly nimble on his feet. By reason of a careful diet, the big fellow scarcely carries an ounce of superfluous weight,” wrote Drebinger.8

A pitching glitch burdened Brown because of size beyond his waistline. In The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers, the authors note, “Brown had very short, stubby fingers, which made it difficult for him to grip a baseball, almost impossible for him to throw a curve.”9

Walter George Brown was born on April 30, 1907, in Greene, Rhode Island, to Adelaird Gotcharles — who died in 1910 from consumption10 — and Sadie Gotcharles (née Benjamin),11 who traced her bloodline back to John and Priscilla Alden. Gotcharles was a French Canadian who found employment in New England textile mills. Sadie remarried; her second husband was named Brown. “I always heard that he died, but I really know very little about him,” Walter’s daughter Walda Cameron said. “Dad seldom spoke of him. He had not been a presence for years before I was born in 1941 and Sadie never mentioned him that I can remember. I can’t tie him in as a formative factor in my father’s life. A third marriage happened in 1955, to Fred Lawton in Florida.”12

It was Sadie who might have provided a genetic link to her son’s weight. She stood 6 feet tall and hovered close to 300 pounds. Her brother, Henry, had a physical similarity: 6’4” and “heavily framed,” according to daughter Walda.13

Alternating between the minor leagues and the major leagues — seven teams in the former, five in the latter — Brown had a career spanning 1925 to 1941.

Rabbit Maranville, managing the Cubs, learned of the 17-year-old Brown — then weighing 196 pounds — through a friend. What Maranville found was a paper-thin résumé consisting of sandlot baseball in Brockton, Massachusetts;14 there was a highly significant size disparity between the manager and his oversized discovery — Maranville stood at 5-feet-5. Brown had the opportunity to showcase his skills in a workout during a Cubs road trip to Boston. Any thoughts of lasting the season were dashed when Maranville quit. George Gibson took over the club, assessed his roster, and sent Brown packing.15

After the two games with the Chicago Cubs in his rookie season, Brown played his sophomore professional season with the Sarasota Gulls in the Class D Florida State League, pitched in 47 games, and compiled an 11-18 record. Infielder Ivy Olson was the only other 1926 Gull to later play in the major leagues.

Brown joined the Cleveland Indians in 1927, but bounced to two minor-league teams that year — the Class A Southern Association’s New Orleans Pelicans and the Class D Cotton States League’s Gulfport Tarpons. His minor-league tenure gave him more mound opportunities — eight games and an 0-2 record with Cleveland; 25 games and a 7-4 record with New Orleans; and 22 games and a 7-8 record with Gulfport.

Returning to Cleveland in 1928, Brown played in five games as a relief pitcher, threw for 14⅔ innings, and added an 0-1 record to his career stats. He also got mound time with the Pelicans, notching a 2-2 record, and the Omaha Crickets in the Class A Western League, where he fared a little better with a 4-3 record.

Brown went 10-17 for Omaha in 1929. But his 1930 season with the Western League’s Oklahoma City Indians showed dominance with a 16-6 won-lost record in 29 games; he led the league in strikeouts and earned runs. In 1931, he played for the Double-A International League’s Jersey City Skeeters, compiling a 10-12 record in 30 games.

During the same January week in 1932 that Franklin Roosevelt announced his candidacy for president, Brooklyn’s ballclub officially adopted the name “Dodgers,” and the Winnie Ruth Judd murder trial began jury selection, a turning point occurred for Brown — the Yankees signed him to a contract.16

Heading to St. Petersburg a month later for spring training with 31 other players — including potential batterymates Bill Dickey, Arndt Jorgens, and Thomas Padden — Brown found himself alongside a gang of greatness.17 What Consolidated Edison is to electricity, the Yankees organization was to baseball in the late 1920s and early 1930s — an icon of power. This season of excellence saw hitting clinics by the pinstriped princes destroying American League pitching, reaching a 107-47 won-lost record, and sweeping the Cubs in the World Series. Batting averages were .349 for Lou Gehrig; .341 for Babe Ruth; .300 for Tony Lazzeri; .310 for Dickey; and .299 for Ben Chapman. Gehrig banged out 208 hits (including 42 doubles), knocked in 151 runs, and scored 138 times. Ruth smashed 41 home runs, notched 137 RBIs, and drew 130 walks to lead the team.

The 1932 season did not begin on an auspicious note for the pitcher recently transplanted from Jersey City. On February 27, a line drive headed straight for his midsection during batting practice resulted in a “bruised side” and placement on the disabled list.18 Brown healed quickly enough to return to BP duties two days later.19

In a spring training game against the Indianapolis Indians on March 29, Brown became the first pinstriped hurler to get pulled from the mound in 1932; it happened during a seven-run fourth inning for the Indians. Brown faced a two-out, man-on-second scenario when he was yanked. “[A]fter a promising showing in his earlier starts, [Brown] has pitched unevenly in his last two showings,” reported William E. Brandt in the New York Times.

When he got sent to the showers, Brown had been ripped for five singles, one double, and two walks.20 Faltering again in a game against the Memphis Chicks, Brown muffed a comebacker when he made a wild throw to first base, allowing the winning run to score.21 During an exhibition game in May, Brown tallied a 5-3 win against the Bridgeport Eastern League team.22

Contributing a 5-2 record in 19 regular-season games, Brown had three opportunities to be a starting pitcher on a dominating staff in 1932: Hall of Famers Lefty Gomez (24-7), Red Ruffing (18-7), and Herb Pennock (9-5); George Pipgras (16-9); Johnny Allen (17-4); and Danny MacFayden (7-5).

In his first start of the 1932 season, Brown gave a clutch performance during the second game of a doubleheader against the Tigers — five hits in 10 innings, four strikeouts, one walk. Score: 4-1.23 Four days later, Brown, described by Brandt as the “newly discovered Yankee ace,” kept goose eggs on the scoreboard for the Chicago White Sox in a 3-2 victory.24 His success continued in a game against the Red Sox — his third complete game in 1932. Shutting out the fellas from Fenway Park 3-0 boosted Brown to a 3-0 record in his starts.25

One of the Yankees’ rare examples of failure came on June 1, when the Philadelphia Athletics won both games of a doubleheader at Shibe Park by one run. In the first game, which went 16 innings, Brown relieved Ruffing after the 11th inning, pitched innings 12 through 15, and allowed two hits. With the score tied at 6-6 in the ninth, the game remained at that tally until the 16th, when Earle Combs doubled, moved to third on a fly ball by Joe Sewell, and scored on Ruth’s single.

A’s outfielder Mule Haas singled to start the bottom of the 16th, then second baseman Max Bishop, sent one over the fence — his first hit in eight at-bats that day.26

On June 14 against the Cleveland Indians, Brown successfully closed a game that saw a rare offensive feat — a triple steal. Ruth walked to begin the seventh inning, Ben Chapman singled, and Lazzeri got an intentional walk. Lyn Lary was hit on the hand, forcing Ruth home. Then the trio of Yankees on base — Chapman, Lazzeri, Lary — took off. Chapman scored.27 The Yankees beat the Indians, 7-6.

Brown played with the Yankees again in 1933, signing his contract in January.28 He was reported as weighing 265 pounds in March.29 In a game against Army’s baseball team at West Point, Brown gave up four hits, struck out 14, and shut out the Cadets, 9-0.30 One of the four cadets on the mound for West Point that day was Ken Fields, who later retired from the Army as a brigadier general.31

More flashes of excellence emerged in a relief appearance against the A’s at Yankee Stadium in early June; the final score looked as though it belonged at a football game.

Facing Don Brennan, the A’s nearly went around the batting order twice with 16 at-bats in the second inning. Danny MacFayden relieved Brennan, but it was to no avail. Brown went to the mound with the A’s cresting on a cushion of an 11-4 score, kept them scoreless for the next 6⅓ innings to end the game, and struck out 12. The Yanks clobbered the A’s pitching and won, 17-11.32

Brown’s production in 1933 was formidable, considering his opportunities: 21 games, 8 saves, 7-5 won-lost record. For 1934, Brown found himself about 20 miles west, playing for the Newark Bears in the International League.

The Newark Evening News praised the arrival. Bears skipper Bob Shawkey, in his first season helming the club, had a familiarity factor with Brown; Shawkey managed the husky hurler in 1931 with the Skeeters, when Brown struck out 118 in 203 innings, and was “second in earned-run effectiveness in the league. And a record like that, with a nondescript club like Jersey City, speaks volumes for Jumbo’s possibilities in the International [League] this year.”33 Additionally, the News noted Brown’s weight, which was several dozen pounds less than the 295 figure cited later in his career: “His fast ball is declared by dazzled batsmen to have every ounce of that 225 pounds behind it and his tremendous hands make pitching tricks easy for him.”34

It was a wise decision to acquire Brown, who led the IL in earned-run average and finished the season at 20-6. His 20th victory came in his last regular-season game, a 3-0 win against the Baltimore Orioles; Brown ended the season with 33 consecutive scoreless innings.35

After his success in Newark, Brown returned to the Bronx for 1935 and 1936. In 1935, he played in 20 games, started eight, saved eight, and went 6-5. On August 20, 1935, Brown’s weight was reportedly 265 pounds.36

Brown and Arndt Jorgens signed with the Yankees in January 1936.37 In an exhibition against the Atlanta Crackers of the Class A Southern Association in early April, Brown was on the hill as a relief pitcher when the mercury plunged to 38 degrees, not too far from freezing. The Yankees won, 9-8.38 Productivity dropped slightly — 20 games played, three games started, one game saved, and a 1-4 record.

Press accounts continued to note Brown’s weight: 268 pounds on April 11,39 268 pounds on June 24.40

Returning to Newark with infielder Ellsworth “Babe” Dahlgren in 1937, Brown had increased his weight, which fluctuated between 260 and 280 pounds.41 And he couldn’t work out because the Bears didn’t have a uniform available to fit his oversized frame. A similarly gargantuan player, Bob Kline of the Buffalo Bisons, offered a remedy of sorts by lending his uniform during a Bears road trip to western New York.42

Brown’s second tenure in Newark didn’t last long — on June 7, the Cincinnati Reds bought his contract.43 In his first start as a Red, the Cincinnati Enquirer noted his weight as 280 pounds.44 Brown lasted seven innings and got the win; Cincy beat the Boston Braves, 6-2.

He lasted about a month in the Queen City before the New York Giants saw an opportunity for their International League team, the Jersey City Giants. Leaving Cincinnati with a 1-0 record, Brown joined outfielder Phil Weintraub, another Reds ballplayer, in heading back to New Jersey.

With the New York Giants, Brown went 1-0 in four games. They lost the World Series to the Yankees in five games, but Brown did not play.

Brown signed with the Giants for 1938.45 During spring training, New York Times sportswriter John Drebinger described Brown’s modus operandi in addressing his weight: “The good-natured Brown, who accepts with an air of resignation whatever weight-reducing methods are prescribed for him, already has shed sixteen pounds.”46 Drebinger also noted that Brown kept a negative attitude toward pinstriped sins in seasons past: “For, while extremely good natured, it still rankles him when he recalls how the Yankees never really gave him a fair shake.”47

Giants manager Bill Terry implemented “diligent immersions in the hot baths” at spring training in Hot Springs, Arkansas, to reduce weight for Brown and similarly girth-laden teammates Don Brennan, Hank Leiber, and Freddy Lindstrom.48 A friendly spring-training wager turned into the basis for a bickering contest between Leiber and Brown — the former bet a dollar that Brown couldn’t hit the ball past the infielders. Breaking good will and the tenet of good faith in every contract, Leiber pushed his infielders to the outfield. Brown popped up.49

When the team moved to Baton Rouge, a jolt of fear went through the camp — Brown, Sambo Leslie, Bill Lohrman, and Tom Baker were in a car that went into a ditch after crashing into another car. Brown had “a slight bruise on this arm and another on the ribs.”50 He had another minor injury when his right pinky finger was smacked by a line drive during batting practice.51 It became crooked and stayed that way for the rest of his life.52

Brown played in 43 games in 1938, the most for a season in his major-league career. He closed 32 games, saved five, and added a 5-3 record to his stats. When he went to spring training in 1939, Brown was sick, perhaps a residual effect of his bronchial pneumonia during the winter.53 A few days later, he pitched in an intramural game.54 In June, Brown faced injury after a rain-soaked 7-2 victory over the Reds when he “slipped on the dugout steps and sprained an ankle so badly he has been sent back to New York.”55 It was another solid year for Brown — six saves and a 4-0 record in 31 games.

On February 23, 1940, Brown boarded a train at Pennsylvania Station with Lohrman, Steve Tramback, Tom Gorman, and Ken O’Dea heading for Winter Haven, Florida, to get ready for another season of Giants baseball.

Plowing through National League lineups, Brown attained a winning streak of six games across three seasons — from August 20, 1938, to May 7, 1940, he went undefeated in 45 games (84⅓ innings). It was a team record. A Giants press release emphasized previous winning streaks for Carl Hubbell (24 games in 1936-1937) and Rube Marquard (19 games in 1912) while noting a new standard for relief pitchers — “his record may stand for a long time as a shining mark for bull-pen firemen in effective emergency aid.”56

A standout performance came on June 8, when he saved both games of a doubleheader against the St. Louis Cardinals.57

Brown finished the season at 2-4 with a league-leading seven saves and led the league again in 1941, his last season, with eight saves; his won-lost record was 1-5.

Maintaining evenness in his psychology regarding mound duties, Brown acknowledged that wins and losses attributed to him might, in both cases, be unwarranted. “Sometimes a relief pitcher will land a win he hardly deserves, and then again he’ll go a long time without getting a nibble of notice,” said Brown in 1940. “It’s like fishing. I enjoy fishing, next best to baseball, and when you’re out with a line in a boat you can’t tell when you’re going to make a big strike, or get nothing.”58

An aura of affability enveloped Brown, prompting notice from the press, along with a skill set prized by his squads. “[A] good workman at his specialty of pinch pitching, and a fellow who radiated friendliness and good humor,” wrote Will Wedge of the New York Sun upon Brown’s departure from the game in 1941. Wedge noted that the Giants exchanged Brown for lefty Tom Sunkel, who went 15-11 for the Syracuse Chiefs in the International League.

During World War II, Brown was part of the war effort on the home front, working at defense contractor Grumman;59 it was less than a 20-minute drive from Freeport, Long Island, where Brown had settled around the end of his career,60 to Grumman’s headquarters in Bethpage.

As Americans celebrated V-E Day and V-J Day, Brown embarked on a new career that tied into his old one — he opened an eponymous sporting-goods store “at the end of the war,”61 located at 15 West Sunrise Highway in Freeport. Patrons and passersby saw the name “Jumbo Brown,” a silhouette of a right-handed pitcher, and the phrases “Sports Equipment” and “Fishing Tackle-Bait” adorning the storefront. At night, they were lit up. “He had the name emblazoned in neon. It was on all his stationery and on decks of playing cards he used for promotions,” remembered daughter Walda.62

A cornerstone of commerce in Freeport, Brown’s store sponsored a team in a women’s bowling league. Despite renown as a local celebrity, though, the former pitcher couldn’t make the debits and the credits line up on the balance sheet. “The store was successful for a while. But in 1953, he went bankrupt,” said Walda. “I recall that he attributed this to the many chain stores that could undercut him. We sold our home in Freeport and moved to Florida. I know he considered becoming a sports announcer (baseball, of course), but his health was failing even then. By Christmas 1955, we were living in his mother’s home in Providence, Rhode Island. He was at death’s door suffering with cardiovascular dysfunction. His strength was astonishing. He rallied, we returned to Freeport, and, after a time working the tolls at Long Beach, he eventually landed the position as games supervisor at Jones Beach. This was the job he held until his death.”63

Not a figurehead job given because of his notoriety, it required management skills, mentorship, and commitment. “He oversaw maybe 15 mostly college-age boys and he was responsible for maintaining and operating the roller-skating rink, shuffleboard courts, and other related sporting facilities,” said Walda. “The young men he supervised admired him. He was scrupulously fair and consistent. He never played favorites.”64

Brown had married twice. His first wife was Martha Tobe, whose hometown was Lead, South Dakota, a small mining town built to exploit the Homestake Mine, at one time, the biggest gold mine in the country.65 They had a daughter, Faith Emmaline.66

“To my knowledge, Martha and my dad were divorced long before he met my mother (Mildred),” explained Walda. “Unfortunately, I have met Faith only twice in my life — once when I was 7 and again when our father died. We have never corresponded. As far as I know, she settled in New Orleans.”67

Brown’s second marriage demanded subterfuge. “When dad was with the New York Giants, mom was a nurse at the Polo Grounds, which had a rule that married couples could not hold jobs simultaneously,” Walda said. “They married on February 2, 1940, and kept it a secret until the season ended. Only Sarge Haser, head of security at the park, knew about it. He helped facilitate the deceit.”68

Born the following year, Walda remembered her father’s storytelling skills capturing the attention of fans and friends alike. She recalled, “I have a childhood memory of sneaking out of bed one night when my parents were entertaining. I peeked through the stairwell railings to see my father in the living room, seated in a wooden chair, surrounded by a rapt audience. He was demonstrating how he held the ball for various pitches.

“He was a good storyteller, and his career in baseball, his friendships with great names, gave him the stories. He was frequently asked if Babe Ruth really pointed to where he intended to hit the ball. Dad swore he did. ‘Absolutely,’ he’d say. ‘I was there. I watched him do it.’”69

Brown fostered good will in the Freeport community, a product of his jovial nature, civic commitment, and stature as a small-business owner. In his column “Around Town” for the Leader, a local newspaper, Curt Brall labeled Brown in 1951 as “probably one of the best liked business men in Freeport.”70 Further, Brall wrote, “Today, he enjoys the friendship of thousands in Nassau County and is considered one of the much desired after-dinner speakers of this area. Fellows like ‘Jumbo’ Brown make living in a community worth while.”71

Perhaps the most fulfilling of Brown’s civic actions was founding Freeport’s Little League in the early 1950s.72

Beyond sharing anecdotes, opinions, and insights about baseball to an audience, Brown took up the mantle of the press. “After he retired, he wrote a newspaper column called ‘The Bull Pen’ for the Nassau Reporter,” Walda said. “He discussed current baseball goings-on as well as reminiscences from his own career.”73

His writing matched his oratory, full of humility, pride, and, on occasion, self-deprecation. Upon being invited by the Yankees to participate in their 1951 Old-Timers’ Game, Brown wrote, “Evidently the Yankees do not think I have changed much. Guess they think it was impossible for me to get any larger than when I was playing with them. Little do they know I now wear a 54 and Omar, The Tent Maker is my tailor, because they asked me to get into uniform and pitch a bit. But I’ll be there and glad to see everyone, uniform or no uniform.”74

Brown gave up the only runs in the three-inning contest honoring the 50th anniversary of the American League’s birth, the managerial tenures of Joe McCarthy and Miller Huggins, and players representing every pinstriped pennant-winning team (17 in all). Relieving Bob Shawkey, Brown began the third inning. With Lefty Gomez on second base, Frankie Crosetti bashed a four-bagger off Brown; it gave the McCarthys a 2-0 victory over the Huggins-Stengels (the latter name belonging to then manager Casey Stengel).75

In his March 22, 1951, column, Brown recounted an embarrassing scene from his playing days with the Pelicans. When called upon to coach third base in a game against the Birmingham Barons, he took a premature action. “I lumbered off to the third base coaching box, and proceeded to yell, come on boys let’s give this bunch from Birmingham a good shellacking today, at the same time jumping up and down, in the box, clapping my hands and yelling for a hit. Imagine my embarrassment when I finally realized that the Barons were the club at bat and I was coaching for them.”76

A one-sheet biography in Brown’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum states that hobbies included photography — sports action was of particular interest. Brown also engaged in dog breeding and raising.77 “He never bred dogs,” Walda clarified. “We adopted many dogs, cats, and rabbits, but we never bred them. He did have a darkroom in the basement because of a passing interest in photography. Fishing would have to take prominence as his primary hobby. We always had to live by the water, always had boats. Around 1951, he bought a 32-foot cabin cruiser. I remember going crabbing at night in a rowboat, a Coleman lantern slung over the side, along the bays bordering Freeport.”78

“Dad would catch his fish and come right home and cook it. He loved fresh-caught bluefish, broiled, with dollops of butter on top. He was a good cook. He would go crabbing, bring home a bushel of blue-claws, and make a huge pot of gumbo. It was delicious. He learned Creole cooking when he played in New Orleans. Mom said that after one of his cooking sprees, she would find forks balanced on top of the window frames.”79

On October 2, 1966, Brown died of congestive heart failure; pneumonia and a cerebral hemorrhage contributed to his death. Once thought indestructible to fans, opponents, and teammates because of his girth, Brown had hypertension arteriosclerosis for 15 years.80 He is buried at Pinelawn Memorial Cemetery in Farmingdale, New York. Two former employees who worked for Brown while they were in college pursuing careers of the cloth — the Rev. Richard Gray and the Rev. Allan Merrill — conducted Brown’s memorial service.81

A letter from Mildred Brown to Lee Allen, apparently written just a few days after her husband’s passing, recounted a story for the Hall of Fame historian from four years before, when the former pitcher employed covertness to indulge when he bounded from a hospital oxygen tent to the bathroom for a cigarette.82

In a handwritten letter to Allen and Baseball Hall of Fame director Ken Smith, apparently written on the day that Brown died, Mildred notified them that her husband had suffered “a massive stroke and died two weeks later.”83 Reminding Allen and Smith of a trip to Cooperstown and the famed baseball shrine — and thanking them for their kindness — Mildred wrote, “When we left the Hall of Fame that day after our delightful visit with you, he paused on the steps and said, “I don’t care if I die tomorrow. As long as this Hall stands, I’ll be remembered.”84

Acknowledgments

Jumbo Brown’s daughter, Walda (Brown) Cameron, provided invaluable family information. In some cases, more than one email thread occurred on one day between her and the author. For purposes of consolidation, they are considered to be part of one email exchange on that day and are cited as such.

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 A 1934 article in the Newark Evening News marks Brown’s height at 6-feet-4. Hy Goldberg, “Lost Ounce of Tonsils, but Found 68 Unwelcome Pounds,” Newark Evening News, April 19, 1934.

2 Ibid. Goldberg indicates that Brown worked out at the YMCA.

3 Ibid. John Drebinger, “Giants Will Play Athletics Today,” New York Times, March 22, 1938. James P. Dawson, “Terrymen Triumph on Blow by Witek,” New York Times, August 22, 1940.

4 Will Wedge, “Relief Men Star for Giants: But Big Brownie, Despite Fine Work on Trip, Has Yet to Gain Credit for Victory,” New York Sun, June 11, 1940. Jack Singer, “Giant Ace’s ‘Spitfire’ Turns Into a Balloon,” New York Journal-American, August 21, 1941.

5 Lee Allen, The Hot Stove League (New York: A.S. Barnes and Co., 1955), 55.

6 John Drebinger, “Brown and Hafey of Giants Sign; 15 Contracts Already Received,” New York Times, January 20, 1939.

7 John Drebinger, “Giants’ Band Gay on Jaunt in Rain,” New York Times, February 26, 1939.

8 John Drebinger, “Pitchers Working Under Terry Are Giants in More Than Name,” New York Times, March 17, 1939.

9 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 146.

10 Walda (Brown) Cameron, email to author, March 9, 2018.

11 Ancestry.com states his name as George Walter Brown. ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/70595191/person/150083510418/facts?_phsrc=QBO3&_phstart=successSource. He is sometimes called Walter George Brown in press accounts. Adeland Gotcharles’s first name looks as though it might be Adelaird because of a dot above the last part of the name in the 1910 US Census, which is handwritten. 1910 US Census, Ancestry.com, ancestry.com/interactive/7884/4449576_00423/164345019?backurl=https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/70595191/person/150084706872/facts. Walda (Brown) Cameron also indicates that the name “Adelaird” is on the back of the one photograph that she has of her biological grandfather. Walda (Brown) Cameron, email to author, March 9, 2018.

12 Ibid.

13 Walda (Brown) Cameron, daughter of Jumbo Brown, editorial comment to draft of bio, March 8, 2018.

14 Hy Goldberg, “Bear Teams, ‘Varsity and Juniors,’ to Meet at Clearwater Camp Today: Regulars Choose Fallon to Tame Rookies’ Bats,” Newark Evening News, March 20, 1934. “He never had engaged in athletics in school but began fooling around with a sandlot outfit in Brockton, Mass., after he left school.”

15 Ibid. The article states that the workout happened in the “Summer of 1925,” which indicates that it took place when the Cubs were in Boston for a two-game series against the Braves on July 20-21.

16 “Three More Sign Giants’ Contracts,” New York Times, January 22, 1932.

17 “Yankees to Take 32 Players South,” New York Times, February 3, 1932.

18 William E. Brandt, “Dickey of Yankees Arrives at Camp,” New York Times, February 29, 1932.

19 William E. Brandt, “Hill Joins Yanks; Two Holdouts Left,” New York Times, March 1, 1932.

20 William E. Brandt, “Yanks’ Rally Beats Indianapolis, 12-8,” New York Times, March 29, 1932.

21 William E. Brandt, “Ruth Hits Homer, but Yanks Bow, 7-6,” New York Times, April 3, 1932.

22 “Yanks Win Exhibition,” New York Times, May 5, 1932.

23 William E. Brandt, “Yanks Win Twice From the Tigers,” New York Times, September 11, 1932.

24 William E. Brandt, “Yankees Conquer White Sox, 3 to 2,” New York Times, September 15, 1932.

25 William E. Brandt, “Yankees Triumph Over Red Sox, 3-0,” New York Times, September 24, 1932.

26 Richards Vidmer, “A’s Trip Yankees Twice, 8-7, 7-6, 1st in 16th on Bishop’s Homer and 2d on Foxx’s 18th,” New York Herald Tribune, June 2, 1932.

27 William E. Brandt, “Triple Steal Aids in Beating Indians,” New York Times, June 15, 1932.

28 John Drebinger, “Six Yanks Sign, One a Newcomer,” New York Times, January 31, 1933.

29 James P. Dawson, “Yankees Bow, 4-2, as Brown Falters,” New York Times, March 15, 1933.

30 “Yanks Turn Back Army Nine by 9-0,” New York Times, April 11, 1933.

31 Military Times, “Hall of Valor,” valor.militarytimes.com/recipient.php?recipientid=104199.

32 John Drebinger, “Yankees’ 10 in 5th Swamp Athletics,” New York Times, June 4, 1933.

33 “Hurler Comes on Option, Infielder Sent Outright,” Newark Evening News, January 11, 1934.

34 Ibid.

35 “Newark Conquers Baltimore, 3 to 0,” New York Times, September 8, 1934.

36 James P. Dawson, “Yankees Stop Tigers, 7-5, Selkirk Pounding 5 Hits,” New York Times, August 20, 1935.

37 James P. Dawson, “Gorman Named Business Manager of Dodgers to Fill Quinn’s Post,” New York Times, January 29, 1936.

38 James P. Dawson, “Yanks Top Atlanta in Frigid Game, 9-8,” New York Times, April 4, 1936.

39 James P. Dawson, “Ninth Inning Rally Gives Dodgers Third Victory in Row Over Yanks,” New York Times, April 11, 1936.

40 John Drebinger, “White Sox Halt Yankees, 13-4, With 9-Run Onslaught in Sixth,” New York Times, June 24, 1936.

41 Hy Goldberg, “Yankees Send Two to Bears,” Newark Evening News, May 8, 1937.

42 Hy Goldberg, “Brown Hard to Suit,” Newark Evening News, May 14, 1937. “By stretching a point here and there, mostly there Mr. Brown is able to wriggle into Mr. Kline’s uniform, so when the ball game was called off yesterday, Walter borrowed King Kong’s trappings and worked out for the first time since he joined Oscar Vitt’s ball club.”

43 “Pitcher Walter Brown Sold by Bears to Reds,” Newark Evening News, June 7, 1937.

44 “Redlegs Pile Up Lead on Bees in Opening Inning,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 26, 1937.

45 James P. Dawson, “Gehrig, Back, to Call on Ruppert Today With Demand for $40,000,” New York Times, February 8, 1938.

46 John Drebinger, “Melton of Giants Accepts Contract,” New York Times, February 20, 1938.

47 John Drebinger, “Terry Impressed by Brown’s Zeal,” New York Times, February 24, 1938.

48 John Drebinger, “Giants Leave Spa for Baton Rouge,” New York Times, February 28, 1938.

49 John Drebinger, “Hubbell Shows Mid-Season Form as Giants Hold Spirited Drill,” New York Times, February 27, 1938.

50 John Drebinger, “Bartell Is Absent From Giant Drill,” New York Times, March 1, 1938.

51 John Drebinger, “Giants Top Indians, Gumbert, Melton Giving Only 3 Hits,” New York Times, March 27, 1938.

52 Walda (Brown) Cameron, editorial comment to draft of bio.

53 John Drebinger, “Whitehead’s Delay Vexes Giant Pilot,” New York Times, March 7, 1939.

54 John Drebinger, “Wittig’s Pitching Earns Praise of Giant Players and Coaches,” New York Times, March 10, 1939.

55 John Drebinger, “Giants Again Down Reds, 7-2, With Aid of Homers in First,” New York Times, June 25, 1939.

56 Press Release, “Big Walter Brown in Bullpen Hall of Fame,” May 1940. A handwritten notation of “5 40” is at the top of the copy held in Brown’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

57 John Drebinger, “Giants Turn Back Cardinals, 4-2, 5-2,” New York Times, June 9, 1940.

58 Will Wedge, “Relief Men Star for Giants.”

59 “‘Jumbo’ Brown Is Dead,” Long Island Press, October 4, 1966.

60 Ibid.

61 Ibid.

62 Walda (Brown) Cameron, in answer to questions by author, email attachment, March 8, 2018.

63 Walda (Brown) Cameron, email to author, March 8, 2018.

64 Walda (Brown) Cameron, in answer to questions by author, email attachment.

65 “Homestake Mine,” Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.ind.028.xml. The Homestake Mine closed in 2002.

66 Walter George Brown, Biographical One-Sheet.

67 Walda (Brown) Cameron, in answer to questions by author, email attachment.

68 Walda (Brown) Cameron, editorial comment to draft of bio.

69 Walda (Brown) Cameron, in answer to questions by author, email attachment.

70 Curt Brall, “Around Town,” Leader (Freeport — Nassau County), October 18, 1951.

71 Ibid.

72 “Little League Awards Dinner Monday Night,” Leader, September 6, 1956.

73 Walda (Brown) Cameron, in answer to questions by author, email attachment.

74 Jumbo Brown, “The Bull Pen,” Nassau Reporter, August 16, 1951.

75 Leonard Koppett, “McCarthy Honored During Old-Timers Day Ceremonies at Yankee Stadium,” New York Herald Tribune, September 9, 1951.

76 Jumbo Brown, “The Bull Pen,” Nassau Reporter, March 22, 1951.

77 Walter George Brown, Biographical One-Sheet.

78 Walda (Brown) Cameron, editorial comment to draft of bio.

79 Walda (Brown) Cameron, in answer to questions by author, email attachment.

80 Walter G. Brown Certificate of Death, New York State Department of Health, Office of Vital Records.

81 “‘Jumbo’ Brown Is Dead.”

82 Letter from Mildred Brown to Lee Allen, undated. The letter states that “many good friends” may not yet be aware of Brown’s passing because Mildred did not notify the press. The Long Island Press published an obituary on October 4, so the letter was probably written a few days afterward. Mildred learned the story about the cigarette from her husband’s roommate (“stablemate” sic) in the hospital. She uses the phrase “four years ago,” but it’s unclear whether she heard the story at that time, or learned of it through Brown’s last stay in the hospital.

83 Letter from Mildred Brown to Lee Allen and Ken Smith, October 2, 1966. Although her letter does not have a date at the top, she writes, “As you know at your last meeting with him, he was ill for years with heart trouble and his condition worsened steadily until now. October 2.

84 Ibid.

Full Name

Walter George Brown

Born

April 30, 1907 at Greene, RI (USA)

Died

October 2, 1966 at Freeport, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.