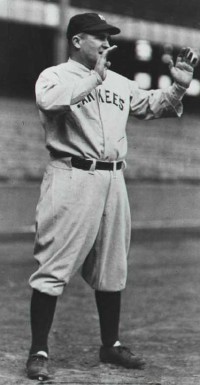

Joe McCarthy

Self-effacing and relentlessly confident, Joe McCarthy was a relatively silent yet authoritative force behind the success of the New York Yankees during 1930s and most of the 1940s. McCarthy’s Yankee teams regularly dominated the American League, and in many seasons New York faced little competition for the pennant. Although he was once famously scorned by Jimmy Dykes as a “push-button manager” who won largely because of his teams’ superior talent, McCarthy’s former players regarded him as indispensable to the success of seven World Series-winning teams in New York.1 “I hated his guts,” said former Yankee pitcher Joe Page, “but there never was a better manager.”2

Self-effacing and relentlessly confident, Joe McCarthy was a relatively silent yet authoritative force behind the success of the New York Yankees during 1930s and most of the 1940s. McCarthy’s Yankee teams regularly dominated the American League, and in many seasons New York faced little competition for the pennant. Although he was once famously scorned by Jimmy Dykes as a “push-button manager” who won largely because of his teams’ superior talent, McCarthy’s former players regarded him as indispensable to the success of seven World Series-winning teams in New York.1 “I hated his guts,” said former Yankee pitcher Joe Page, “but there never was a better manager.”2

The first manager to win pennants in both leagues, McCarthy managed the Chicago Cubs to the World Series in 1929. Overall, his teams won seven World Series in nine appearances, and his career winning percentages of .615 in the regular season and .698 in the postseason remain major-league records. At the end of his career, McCarthy managed the Boston Red Sox. Although his Red Sox teams won 96 games in both 1948 and 1949, he was never able to manage Boston to the World Series, leading many Red Sox fans to view him as aloof and gruff rather than the taciturn managerial genius that so many Yankee fans embraced.

McCarthy was born in Philadelphia on April 21, 1887. When he was only 3 years old, his father was killed in a cave-in while working as a contractor. McCarthy’s impoverished upbringing forced him to do everything from carrying ice to shoveling dirt. Still, his prowess playing baseball in the Germantown section of Philadelphia soon earned him attention. He was a member of his grammar-school team as well as a local team in Germantown.

He broke his kneecap as a youth while playing in Germantown, which likely limited his chance to one day be a major-league player. “It left me with a loose cartilage which cut down on my speed,” said McCarthy. “But I didn’t do so good against a curved ball, either.”3 Even so, McCarthy was productive enough to be offered a scholarship to Niagara University to play baseball starting in the fall of 1905, in spite of never attending high school. McCarthy lasted at college for two years, but the strain of not making any money was too great and he left school to play minor-league baseball.

The 5-foot-8½-inch, 190-pound, right-handed-batting McCarthy signed with Wilmington of the Tri-State League to start the 1907 season. His first game was on April 24, against Trenton, and he got one of his team’s four hits and stole a base while playing shortstop in a 9-3 road loss. In 12 games with Wilmington, McCarthy had seven hits in 40 at-bats without getting an extra-base hit or more than one hit in a game. McCarthy was never much of a hitter, and during his entire minor-league career, he batted better than .300 in a full season only once, when he hit .325 for Wilkes-Barre in 1913.

When manager Pete Cassidy was fired and McCarthy’s job was given to another player, McCarthy jumped to Franklin of the Inter-State League, where he batted a more impressive .314 with two home runs for the rest of the season while making $80 a month. Three and a half years of minor-league ball with Toledo under Bill Armour followed before McCarthy went to Indianapolis of the American Association for the final half of the 1911 season in a trade for Fred Carisch. It wasn’t always smooth in Indianapolis: In a game on April 26, 1911, McCarthy made four errors in seven chances at third base.

In 1912 and 1913, McCarthy played for Wilkes-Barre of the New York State League, where Bill Clymer was the team’s president and manager. Eventually his salary rose to $350 a month. In 1914 and 1915, McCarthy played for Buffalo of the International League, along with future major leaguers Joe Judge and Charley Jamieson.

McCarthy jumped his contract to sign with Brooklyn of the Federal League in 1916, but the league collapsed and McCarthy never got to play for Brooklyn. That period was particularly confusing for McCarthy, as he received a call from the New York Yankees for a tryout around the same time, but he instead received what author Harry Grayson called “the runaround” when the team refused to commit to McCarthy, saying it might be sold.4 Instead, McCarthy spent the final six years of his minor-league career (1916-1921) with Louisville of the American Association after being awarded to the team in the dispersal of players from the Federal League.

In spite of his long minor-league playing career, McCarthy was never able to get to the major leagues as a player. As Joe Williams wrote in The Sporting News in 1939 when McCarthy was in his 14th season as a major-league manager, “More than half of McCarthy’s baseball life was spent in the brambles of mediocrity. He was the confirmed and perpetual busher [in the minor leagues]. He played the tank towns, rode the day coaches, had a gustatory acquaintance with all the greasy-spoon restaurants. He played second base and was an adroit fielder. He hit well enough, especially in the clutches, with men on base. But he was slow. The broken kneecap had left an enduring mark. ‘If it wasn’t for that knee, we’d recommend you,’ the scouts always said.”5

McCarthy was a versatile player during his minor-league career. He began as a shortstop, moved to third base, later became an outfielder, and ultimately found his greatest success at second base. When Bill Clymer left his job as Wilkes-Barre’s manager after the 1912 season, McCarthy received his first managerial job, at the age of 25. He did quite well as the youngest manager in professional baseball, leading his team to a second-place finish only 1½ games behind Binghamton.

McCarthy got the chance to manage again in Louisville. “In those early years in Louisville, I became convinced that I never would set the woods on fire as a player,” he later recalled. “My mind began to work along managerial lines. I studied the systems of successful managers of the period. My chance came midway through the 1919 season when Patsy Flaherty resigned.”6 McCarthy took over as manager of Louisville on July 22, 1919, and won his first game, 6-2. His pitcher that day was Bill Stewart, later a National League umpire.

An insult from a teammate precipitated McCarthy’s retirement as a player. During a game against St. Paul in September 1920, McCarthy was playing second base when St. Paul’s Bert Ellison was caught in a rundown. When Louisville first baseman Jay Kirke made a throw that was too late, the ball hit McCarthy in the chest and went into center field.

“What made you do a thing like that?’ said McCarthy. “Why didn’t you give me the ball sooner?”7

Kirke, according to writer Joe Williams, “looked the manager of the Colonels in the eye and imperiously said, ‘What right have you got trying to tell a .380 hitter how to play ball?’”8

That incident affected McCarthy. According to Williams, “McCarthy was hitting only .220 at the time, so instead of becoming outraged, he bowed to the logic of Mr. Kirke’s criticism, and that night he announced his retirement from baseball as an active player. From that point on, he would sit on the bench and tell the players what to do.”9

After retiring as a player, McCarthy went on to manage Louisville to its first American Association pennant in 1921 (he did play in 11 games that year). The Colonels defeated the Baltimore Orioles in the Little World Series, five games to three. In every year but one after that, McCarthy’s teams finished in the top four in the league. He managed the Colonels for four more seasons, leading the team to a second pennant in 1925. This time the Colonels lost the Little World Series to the Orioles, by an identical five games to three, then played a series with San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League, losing five games to four.

After that season William Wrigley, Jr., the Cubs’ owner, offered the Cubs managerial position to McCarthy. The Cubs in 1925 had, in the words of James Enright, “flopped into the coal hole,” employing three managers and finishing in eighth place in the National League with a 68-86 record.10 McCarthy had hoped to keep word of his new contract with the Cubs out of the press until after the Colonels’ postseason series with the San Francisco Seals, but word that he had signed a two-year contract with Chicago soon leaked out.

Before McCarthy began with the Cubs, writer Irving Vaughn noted: “For several years in the American Association, they have regarded [McCarthy] as sort of a miracle worker, but the new graduate into the big leagues can’t explain his success. He has no pet theories about managing a team. He says he merely studies each individual player under him and then studies the opposition.”11

As Joseph Durso recounted, McCarthy was quickly introduced to the star system when he joined the Cubs. Discussing a strategic scenario in the clubhouse, McCarthy reportedly said, “Now, suppose we get a man on second base? …” Star pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander lit a cigarette and retorted: “You don’t have to worry about that, Mr. McCarthy. This club will never get a man that far.” A month later, McCarthy sold Alexander to the St. Louis Cardinals. Shortly thereafter, Wrigley told McCarthy: “Congratulations. I’ve been looking for a manager who had the nerve to do that.”12

In McCarthy’s first season with the Cubs, the team showed marked improvement. A sportswriter wrote, “There has been more interest in the Cubs in Chicago this year than ever before. Their unexpected showing also stimulated business on the road and it is a fair bet when the team holds its annual meeting President William Veeck will be able to tell the few stockholders that a juicy melon is in the safe ready for cutting.”13

McCarthy’s success, the writer said, was even more remarkable considering that Alexander and Wilbur Cooper were both gone from the pitching staff. “Naturally much credit is being cast in the direction of McCarthy and he seems entitled to every nice thing that is said.”14

The Cubs finished in fourth place in both 1926 and 1927 behind the strong hitting of Gabby Hartnett, Riggs Stephenson, and Hack Wilson. While the pitching was solid if not spectacular, the Cubs struggled to win on the road. Even in 1928, when they finished with 91 wins, it was the team’s struggles to win away from Chicago that kept it from being more competitive.

McCarthy’s managerial decisions paid more dividends in 1929. According to one newspaper account, “It is generally agreed now that McCarthy made a move for improvement when he broke away from the batting layout he had established for himself early in the Spring. This involved only the heavy caliber members of the attack. [Kiki] Cuyler had been third, [Rogers] Hornsby fourth, Wilson fifth, and Stephenson sixth. Now Cuyler has been shunted in fifth place and Hornsby and Wilson have been elevated to third and fourth, respectively.”15

Although McCarthy was never a particular favorite of the media, his managerial style was appreciated early in his career. Said one account in 1929: “[McCarthy] has one quality which endears him to those who know what a manager has to face in the way of heckling. He stands by his players. … Tell him his team is weak here, or weak there, and he will not fly off the handle. On the contrary, he will tell you where it is strong and going along to suit him.”16

While with the Cubs, McCarthy became known by the nickname Marse Joe, a name that followed him throughout his life. Writer Will Wedge contended: “It is suspected that Marse Joe was hung on Joseph Vincent by a Windy City scribe after he had risen from a rather Little Joe, not so very seriously considered at first, to a veritable Master Joe by his forcing the Cubs up from the ruck into a championship in the space of five years. … When you come to think of it that Marse Joe label has a quiet sound, a safe sound. It isn’t the name you’d hang on a person who goes off half cocked. It’s the title of an overseer who’s sane and balanced. And McCarthy is just that.”17

McCarthy’s finest moment with the Cubs ultimately resulted in his undoing there. He led the Cubs to a 95-win season in 1929 and to the World Series. The Cubs, however, lost the Series in five games to the Philadelphia Athletics. Not only did McCarthy’s team lose the first game when Connie Mack surprisingly started aging Howard Ehmke, who won, 3-1, and struck out a then-record 13 batters, but the team also allowed the Athletics to overcome an eight-run deficit in Game Four by allowing 10 runs in the seventh inning, keyed by Hack Wilson’s losing Mule Haas’s fly ball in the sun.

Even with a second-place finish in 1930 supported by Hack Wilson’s National League record 56 home runs, McCarthy was not offered a contract by the Cubs at the end of that season and was replaced by Rogers Hornsby. The 1930 Cubs endured an injury to pitcher Charlie Root in September as well as a particularly weak showing on a late-season East Coast trip.

Still, the loss in the 1929 World Series was never truly forgotten. As Joseph Durso later wrote, “neither the Chicago fans nor Mr. Wrigley ever quite forgave Mr. McCarthy for that.” Wrigley, in fact, was quoted as saying, “I have always wanted a world’s championship, and I am not sure that Joe McCarthy is the man to give me that kind of team.”18 Hornsby also reportedly had “openly censured” McCarthy for using pitcher Art Nehf during that miserable seventh inning in Game Four of the 1929 World Series.19

For whatever lack of enthusiasm followed McCarthy out of Chicago, he was eagerly pursued by the New York Yankees to replace Bob Shawkey. Still, McCarthy’s arrival in New York was held up since he had promised first to talk to the Red Sox about their managerial vacancy. An unattributed newspaper clipping in McCarthy’s Hall of Fame file reports, “The offer [the Red Sox] made was not attractive to him, however, and he felt free to talk to Col. Jacob Ruppert and Edward G. Barrow, which he did last Friday night.”20 In the end, McCarthy turned the Red Sox down for a two-year contract with the Yankees.

Even before McCarthy’s hiring was officially announced by New York, one reviewer thought well of it. Another Hall of Fame clipping reads: “The coming of McCarthy to the Yankees is regarded in New York as a ten-strike for the Yankees and the American League, as well it should be. After all, here is a man who built up a winning team in Chicago and managed it intelligently – so well did he manage the torn and battered Cubs this year that he came within an ace of winning the pennant again. What he will do with the Yankees is, of course, problematical, but the chances that he will be as successful in New York as he was in Chicago are tremendously in his favor. Managerial ability isn’t a matter of geography and a manager who does well in one town should do well in another, provided he isn’t hampered by his new surroundings.”21 Yet there were initial jitters: after McCarthy flubbed Colonel Ruppert’s name during an early meeting with the press, Ruppert replied: “Maybe McCarthy will stay around long enough to learn my name.”22

Babe Ruth, who was said to have been disappointed not to get the New York managerial job himself, reportedly praised McCarthy when the latter was hired and said that the two would get along well. One paper in October 1930 even went so far as to say that “the coming of McCarthy to New York is one of the biggest achievements of the American League since Colonel Ruppert engaged the late lamented Miller Huggins 12 years ago. McCarthy is a figure of national importance. He is enjoying the friendship and sympathy of millions of fans who want to see him vindicated.”23

“I have no illusions about the task ahead of me with the Yankees,” McCarthy wrote in a piece published in the Philadelphia Record in February 1931 (the Yankees had finished third in 1930). “The pitching staff showed signs of crumbling under Miller Huggins (who last managed in 1929).” He cited the arrival of Joe Sewell, which he felt could help form “an efficient infield combination.” McCarthy also placed a lot of stock in rookie players, saying, “This ought to be a pretty good year for the rookie, as I am an American League rookie myself and stand willing to be convinced.”24

So began one of the most impressive managerial tenures in major-league history. In McCarthy’s first 13 seasons with the Yankees, his teams finished in first or second place in every season but one. From 1932 to 1943, his teams won eight American League pennants and seven World Series. His teams won more than 100 games in a 154-game season six times, and the Yankees won 90 games or more 11 times during that span.

Speaking in 1956, McCarthy listed his team’s 1932 World Series victory over the Cubs as his greatest thrill. “Perhaps you understand why,” he said. “First it was my first World Series winner. Secondly, it was against the Cubs.”25

McCarthy’s skill was often praised even while he never was particularly warm or introspective with the media. A representative review appeared in the New York Times of September 24, 1937, after the Yankees had again won the pennant: “McCarthy deserves much credit for this year’s Yankee success, having turned in the best of all his managerial jobs. He won despite a series of injuries to prominent hitters and an epidemic of lame arms which threw the pitching staff out of kilter. As he went along, Marse Joe proved himself to be an excellent handler of pitchers. He manipulated the staff adroitly, especially through the many weeks in which it was not up to full strength.”26

Still, McCarthy’s troubles with the press limited his appeal. Writing in 1950, Arthur Daley remarked, “Marse Joe was never easy to know. He was a suspicious man with the press and it was only on the rarest occasions that he’d let down his guard and talk expansively. Yet even then he’d suddenly whip up his guard and start sparring cautiously.”27

Managing perhaps the broadest collection of stars in major-league history with New York – including Bill Dickey, Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio, Babe Ruth, Tony Lazzeri, and Lefty Gomez, among others – McCarthy was an understated presence, a teacher who insisted on consistent effort and outstanding performance. As Arthur Daley said in the New York Times: “Few men in baseball were ever as single-minded as he. That was to be both his strength and his weakness. Baseball was his entire life and it never was lightened by laughter because he was a grim, humorless man with a brooding introspection which ate his heart out.”28

At the time of his death, Durso remarked: that McCarthy “was a stocky 5-foot-8-inch Philadelphian with a strong Irish face, an inexpressive manner, a conservative outlook – the master of the noncommittal reply and the devotee of the ‘set’ lineup. He had neither the quiet desperation of Miller Huggins who preceded him as the Yankee empire builder, nor the loud flamboyance of Casey Stengel.” As Durso recalled, Joe DiMaggio said, “Never a day went by that you didn’t learn something from McCarthy.”29

With the Yankees, McCarthy maintained strict standards. Shortly after Jake Powell joined the team, for instance, Powell tried to give a teammate a hotfoot while the Yankees were waiting for a train. According to sportswriter Jim Ogle, McCarthy quickly said to Powell: “You’re a Yankee now, we don’t do that.”30

As Joe McKenney recounted, McCarthy insisted that “his ball players play the part of champions at all times. Their dress and deportment in hotels and on trains was always McCarthy’s concern and so successful were his methods that it was always easy to pick out a Yankee in a crowded lobby, even in Boston.”31

McCarthy, as John Drebinger recounted, had “an extraordinary ability in judging young players.” Oscar Grimes, a utility infielder, committed three ninth-inning errors that lost a game for New York. After the game Grimes was sure that he would be sent to the minor leagues. According to Grimes, “Instead, McCarthy slapped me on the back and said, ‘Oscar, you’ll never believe this, but I once had a worse inning than that at Louisville. Now get out there and win this second game for me.’ You know, you’ve got to play your guts out for a man like that.”32

McCarthy also succeeded in managing Babe Ruth. According to one writer, “No matter what his thoughts might have been, Joe ran the rest of his club and left Babe to his own devices. Ruth never bothered Joe much either. He did just about as he pleased, just showed up for the games and gave McCarthy four pretty good seasons. It was hard to tell what he thought of the manager.”33 There were, however, reports that Ruth’s jealousy of McCarthy led to Ruth’s release by the Yankees and signing by the Boston Braves in 1935.

Still, in spite of his successes, McCarthy’s teams were not up to the same standards during the latter part of World War II. From 1944 to 1946 the Yankees never finished above third place, as many of his star players had retired, left for other teams, or gone into the armed forces. On May 26, 1946, in a telegram from his farm at Tonawanda, New York, to team president Larry MacPhail, McCarthy resigned. “It is with extreme regret,” McCarthy wrote, “that I must request that you accept my resignation as manager of the Yankee Baseball Club, effective immediately. My doctor advises that my health would be seriously jeopardized if I continued. This is the sole reason for my decision, which as you know, is entirely voluntary on my part.”34

The New York Times reported that McCarthy had suffered a recurrence of a gall-bladder condition that necessitated his retirement and that he would remain with the team in an advisory capacity. “McCarthy was the most cooperative manager with whom I have ever been associated in baseball,” said MacPhail at the time.35 Longtime Yankee catcher Bill Dickey was named as McCarthy’s replacement. There were also persistent rumors that McCarthy resigned because of a personality conflict with Larry MacPhail, with whom he did not have as close a relationship as he had with Ed Barrow.

Said one contemporary article: “There is no question that McCarthy is a sick man, but the prime reason that he is not returning to the Yankees is not his ailments but Larry MacPhail, new president of the club. … Now apparently the more he cogitates on MacPhail’s blast about the Yankees not hustling, the more determined he becomes to stay in Buffalo and terminate his connection to the club.”36 MacPhail had also publicly scorned McCarthy for a confrontation with Joe Page during a flight from Cleveland to Detroit five days earlier.

After two years out of baseball, McCarthy was hired by the Boston Red Sox. Boston had finished 14 games behind the Yankees in 1947, and McCarthy’s hiring was part of a larger shakeup that included shifting manager Joe Cronin to the general manager’s position. Cronin sounded impressed also: “Joe’s going to have more power than probably any manager since McGraw. He will have complete charge of the team and will have the power to make any deal he wants.”37

Even though McCarthy’s Boston teams finished in second place in each of his two full seasons with the Red Sox, it was not enough to satisfy Boston fans who were eager for him to duplicate the World Series-winning success he had in New York. Boston lost a one-game playoff for the American League pennant to Cleveland in 1948 and finished second to the Yankees in 1949, losing the pennant on the last weekend of the season.

In 1969 McCarthy got together with Ted Williams and recalled that Williams had been the last player to leave the locker room after Boston’s loss in the 1948 one-game playoff. As recounted by Buffalo sportswriter Cy Kritzer:

“ ‘Do you remember what I said to you that day?’ Joe inquired.

“ ‘How could I ever forget those kind words?’ Williams replied. ‘They were the kindest words ever spoken to me in baseball.’

“Marse Joe had told his star slugger, ‘We did get along, didn’t we? And we surprised a lot of people who said we couldn’t.’”38

According to Kritzer, Williams also appreciated how McCarthy never criticized his players in the press.

Still, said Ed Fitzgerald in Sport magazine: “The sportswriters of the town, who greeted [McCarthy] with open arms when he took over the job, have been beating him over the head ever since. Not all of them, but most of them. … They criticize his handling of his players, his relations with the press, his every positive or negative act.”39

And when McCarthy resigned from Boston’s managerial position on July 22, 1950, again citing ill health, his critics were ready to pounce. But an admirer, Arthur Daley, wrote in the New York Times, “Marse Joe failed at Boston. It’s unfortunate that his departure had to come on such a sour note because the small-minded men who don’t know any better will definitely remark that he could never manage a ball club anyway and add that it’s good riddance. They’ll even add that the records are false in proclaiming that the square-jawed Irishman from Buffalo won more pennants than John McGraw and Connie Mack.”40

Retiring to his farm home in Tonawanda, New York, McCarthy was done with professional baseball for good. He liked, as one report said, “to putter around the garden.” In retirement, he was busy: “I don’t have time to do any fishing now, either,” he said in 1970 when he was 83. “This place is big enough to take care of, so I never get out. I do a few things around the house. A little gardening. Not much. I plant tomatoes and beans and stuff like that.”41 He called his home “Yankee Farm.”42 Joe’s wife, Elizabeth McCarthy, died in October 1971 at the couple’s 61-acre farm.43

McCarthy was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1957 along with former Detroit Tigers star outfielder Sam Crawford.

McCarthy died of pneumonia at the age of 90 on January 13, 1979, at Millard Fillmore Hospital, near his home in Tonawanda. He had been hospitalized twice in 1977, once for a fall and later for pneumonia. He was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Tonawanda.

Last revised: February 17, 2021 (ghw)

An updated version of this biography appears in “Winning on the North Side: The 1929 Chicago Cubs” (SABR, 2015), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. It was originally published in “Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (Almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948” (Rounder Books, 2008), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

McCarthy’s biography and World Series statistics on baseball-reference.com.

Clippings from McCarthy’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 Joseph Durso, “Joe McCarthy, Yanks’ Ex-Manager, Dies at 90,” New York Times, January 14, 1978.

2 Joseph Durso, “Whether They Liked It or Not, McCarthy Did Things His Way,” New York Times, November 15, 1978.

3 Harry Grayson, “McCarthy Recalls Pine St. Baseball Parade That Turned Him from Cricket to Diamond.” Unattributed article from player’s Hall of Fame file.

4 Ibid.

5 Joe Williams, “Busher Joe McCarthy,” Saturday Evening Post, April 15, 1939.

6 Harry Grayson, “McCarthy Recalls Pine St. Baseball Parade That Turned Him from Cricket to Diamond.” Unattributed article from player’s Hall of Fame file.

7 Joe Williams, “Busher Joe McCarthy.”

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 James Enright, “Will Luck of the Irish Revive Faded Cubs?” The Sporting News, March 23, 1963.

11 Irving Vaughan, “McCarthy Signs to Pilot Cubs for Two Years: Louisville Manager Closes With Veeck,” Chicago Tribune.

12 Joseph Durso, “Joe McCarthy, Yanks’ Ex-Manager, Dies at 90.”

13 “No Kick on Cubs in Chicago This Time: Joe McCarthy’s Debut Year All That Could Be Asked,” September 30, 1926. Unattributed article from player’s Hall of Fame file.

14 Ibid.

15 “Good for Joe,” July 25, 1929. Unattributed article from player’s Hall of Fame file.

16 Ibid.

17 Will Wedge, “That Marse Joe Nickname,” 1931. Unattributed article from player’s Hall of Fame file.

18 Joseph Durso, “Joe McCarthy, Yanks’ Ex- Manager, Dies at 90.”

19 “Yankees to Sign Joe M’Carthy When Series Moves Off Stage,” October 9, 1930. Unattributed article from player’s Hall of Fame file.

20 Ibid.

21 “Yankees to Sign Joe M’Carthy When Series Moves Off Stage.”

22 Joseph Durso, “Joe McCarthy, Yanks’ Ex-Manager, Dies at 90.”

23 “Yankees to Sign Joe M’Carthy When Series Moves Off Stage.”

24 “McCarthy Admits Yankees’ Hurling Must Stiffen Much,” Philadelphia Record, February 23, 1931.

25 Cy Kritzer, “Marse Joe’s Biggest World Series Thrill? Sweep Over Cubs Who Fired Him,” Sporting News, May 2, 1956.

26 “Yankees Owe Flag Largely to Marse Joe: McCarthy Shows His Ability in Solving Fielding Problems,” New York Times, September 24, 1937.

27 Arthur Daley, “Exit for Marse Joe,” New York Times, June 25, 1950.

28 Arthur Daley, “Delayed Tribute,” New York Times, September 2, 1951.

29 Joseph Durso, “Joe McCarthy, Yanks’ Ex-Manager, Dies at 90.”

30 Jim Ogle, “Joe McCarthy: A Tribute,” My Yankee Scrapbook, 1978.

31 Joe McKenney, “Hub Prospects Rejuvenate McCarthy,” The Sporting News, October 29, 1947.

32 John Drebinger, “Marse Joe Coming Home.” New York Times. Undated. Player’s Hall of Fame file.

33 Leo Fischer, “Joe Welcomed the Honor but Not at Players’ Expense,” February 6, 1957. Unattributed article from player’s Hall of Fame file.

34 James P. Dawson, “McCarthy Resigns: Dickey Yank Pilot,” New York Times, May 1946.

35 Ibid.

36 Charles Segar, “M’Carthy to Quit Yank Post,” July 31, 1945. Unattributed article from player’s Hall of Fame file.

37 Ed Fitzgerald, “Nobody’s Neutral About McCarthy,” Sport, August 1950, 82.

38 Cy Kritzer, “Glory Days Come Alive: Ted Visits McCarthy,” September 8, 1969. Unattributed article from player’s Hall of Fame file.

39 Ed Fitzgerald, “Nobody’s Neutral About McCarthy.”

40 Arthur Daley, “Exit for Marse Joe.”

41 “Marse Joe McCarthy, at 83, Has Scant Time for Baseball,” United Press International, January 14, 1970.

42 “Marse Joe Has 88th,” United Press International, April 22, 1975.

43 “Mrs. Joe McCarthy,” Obituaries, New York Times, October 20, 1971.

Full Name

Joseph Vincent McCarthy

Born

April 21, 1887 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

January 13, 1978 at Buffalo, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.