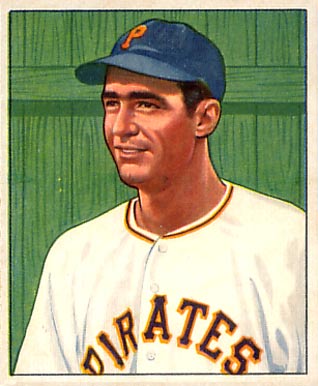

Dino Restelli

“Dino Restelli is a rawboned young man with powerful arms, bushy eyebrows, and a sunny disposition. Like baseball’s famed DiMaggio brothers, he comes from San Francisco’s sandlots. A fortnight ago, upped to the majors from San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League, Dino pulled on a Pittsburgh Pirate uniform, got into the lineup as an outfielder and began cannonading the fences as few pea-green rookies ever had before.” That was Time magazine’s succinct description in 1949 of baseball’s latest phenom.[1]

“Dino Restelli is a rawboned young man with powerful arms, bushy eyebrows, and a sunny disposition. Like baseball’s famed DiMaggio brothers, he comes from San Francisco’s sandlots. A fortnight ago, upped to the majors from San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League, Dino pulled on a Pittsburgh Pirate uniform, got into the lineup as an outfielder and began cannonading the fences as few pea-green rookies ever had before.” That was Time magazine’s succinct description in 1949 of baseball’s latest phenom.[1]

At the age of 24 Dino arrived in Pittsburgh from San Francisco, where in 72 Pacific Coast League games he had hit.351 with 10 home runs and 65 runs batted in for his hometown San Francisco Seals. Pirates manager Billy Meyer immediately inserted Restelli into the third slot in the batting order, ahead of slugger Ralph Kiner. On June 14, 1949, at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, Restelli went 0-for-4, walking once in a 4-3 win over the Boston Braves.

On day two Restelli faced Boston left-hander Warren Spahn. He homered twice, singled, and drove in five runs, leading the Pirates to an 8-7 come-from-behind victory.

Time rhapsodized. “His first home run, smacked from a wide-legged, right-handed stance, was a tremendous wallop that cleared Forbes Field’s left-field fence by a good 75 feet. His second, landing on top of the scoreboard, brought a gasp of admiration from teammate Ralph Kiner, the league’s home-run leader….”[2]

Restelli continued to hit for average and power through the remaining two weeks of June, finishing the month (15 games) with a .356 batting average, a .424 on-base percentage, a .763 slugging average, seven home runs, and 16 RBIs. Besides the two home runs off Spahn, he hit two off Robin Roberts and one each off Curt Simmons, Ralph Branca, and former Seals’ teammate Larry Jansen.

In their first 11 games together Pittsburgh outfielders Restelli, Kiner, and Wally Westlake racked up 50 hits, 13 home runs, and 31 RBIs. For a month or more they were touted as the best right-handed-hitting outfield in the National League.[3] Frankie Frisch, the former Pittsburgh skipper then managing the Chicago Cubs, called them a “right-handed Murderers’ Row.” In only two of the first 35 games they played as a unit were they hitless. The trio came up with 124 hits, 28 home runs, and 87 RBIs.[4] At one point the Pirates won 18 of 25 games before cooling off and finishing the season in sixth place.

Restelli’s hot hand also cooled off considerably, and he finished with a .250 batting average, 11 doubles, 12 home runs, and 40 RBIs in roughly half a season with the Pirates. The next season he was back in the minors, the shooting star having fizzled out. Why? The reasons have long been debated. Was it a problem with his eyesight? Did his eyeglasses fog up too often in the humidity of East Coast ballparks? Was he jinxed by an at-bat-from-hell against the fireball pitcher Ewell Blackwell? Or was he just not that good?

Dino Paulo Restelli was born in St. Louis on September 23, 1924, to Paulo and Angella Restelli, natives of Italy. He was their second child (a sister, Josephine, had been born in 1922) and first of two sons (a brother, Paulo, was born in 1930).[5] As a youngster in St. Louis, Dino followed both the Cardinals and Browns. He joined the Cardinal Knot Hole Gang and rooted for his favorite Cardinal, outfielder Ducky Medwick.

The Restelli family moved from St. Louis to San Francisco when Dino was 12. The family lived at 1640 Grant Avenue in San Francisco’s North Beach section, where his father worked as a chef at the nearby Montclair Restaurant. An article in Baseball magazine after his half-season with the Pirates said that Restelli’s parents encouraged his desire to play ball and always made sure their son used a “good glove.”.[6]

On the playgrounds, in the summer leagues, on the high-school fields, and later in the weekend semipro leagues, Restelli could hit them and hit them far.[7] In 1942, his senior year at Galileo High School, he joined future major leaguers Charlie Silvera and Bobby Brown on the all-city team as a first baseman.[8] Galileo won the city championship, losing but one game in Restelli’s senior year; besides Brown (a future physician and president of the American League) his teammates included future major-league manager Frank Lucchesi.[9]

The San Francisco area fielded many semipro baseball teams, and during the early 1940s many of them used high-school players to complete their rosters – young players who not only watched baseball but also played it. Restelli and others honed their skills in these leagues. One team in particular, the Keneally Yankees, sponsored by a local bar, was noted for the number its alumni who turned professional.[10] Many were signed by the New York Yankees at the recommendation of scout Joe Devine. Restelli played for the team, along with future pros Bob Patterson, Charley Silvera, Fenton Mole, Carl DeRose, Bill Wight, and Jerry Coleman.[11]

Restelli broke in with the San Francisco Seals in 1944 at the age of 19.[12] Reports vary as to how exactly he became a Seal. Some reports indicate that local writer and broadcaster Jack McDonald recommended him to Seals president Charlie Graham after seeing him play for the semipro Simmons Mattress team; other reports leave out the McDonald-Graham link.[13]

After 38 games with the Seals, in which he hit.343, Restelli was drafted into the Army, and he served in the South Pacific with the Corps of Engineers in 1945 and 1946.[14]

After his discharge in 1946, Restelli rejoined the Seals, playing in 26 games toward the end of the season. After playing in 119 games with the Seals in 1947 (.292, 10 home runs), he played in 145 games in 1948, batting .289 with 43 doubles, 8 triples, and 10 home runs. He started with the Seals again in 1949, but Pittsburgh scout Ted McGrew watched him for a few weeks as he drove in 65 runs in 72 games, and he urged the Pirates to acquire him. On June 13, 1949, Restelli went to the Pirates in exchange for $25,000 and two players, outfielder Cully Rikard and pitcher Hal Gregg. [15]

At 6-feet-2 and a solid 192 pounds with broad shoulders, Restelli looked more like a college-football linebacker than a minor-league outfielder. His teammates called him Dingo, a nickname hatched during his Pacific Coast League days when a local fan, a girl who couldn’t pronounce his name correctly, repeatedly called him Dingo when the Seals visited San Diego.[16]

In an article under his byline in the New York Journal-American in 1949, Restelli praised Seals manager Lefty O’Doul for giving him sound hitting advice and Seals owner Charlie Graham for encouraging him to start wearing glasses.[17]

In the ensuing years, a rookie who starts with a burst of home runs is frequently compared to Restelli. Most rookies eventually cool down, as Restelli did in 1949; his offensive numbers steadily declined until finally his manager benched him in favor of a slap-hitting rookie, Tom Saffell. There was an outpouring of opinions from teammates, opponents, reporters, managers, coaches, fans, and Dino himself once his blistering pace subsided: “The kid came up too fast” or “The kid can’t handle the curveball” or “The kid lost his confidence after Ewell Blackwell nearly decapitated him,” or “The kid has too many holes in his swing.” [18]

Ralph Kiner liked Restelli’s approach and mechanics. In an early scouting report he disagreed with Restelli’s critics: “Dino’s a great hitter,” Kiner said in July 1949. “He has a good stance at the plate, good wrist action, and good follow-through. He takes a short stride and isn’t fooled too often. He has shown he can hit every kind of pitch, too.” Kiner added that he’d seen Restelli belt both low and high pitches for homers as well as curveballs, fastballs, and off-speed pitches. More importantly, Kiner said, Restelli had a great attitude because “he’s always willing to learn and keeps asking for advice.”[19]

Restelli did have one major problem. His glasses fogged up during the hot, humid East Coast summers, so he kept a bright red bandana in his back pocket to clean his spectacles. His habit of calling time so that he could clean his glasses often riled opponents.

Former Pittsburgh manager Danny Murtaugh, a teammate of Restelli’s in 1949, thought he knew the reason for Dino’s flameout. Murtaugh’s explanation: Restelli came to bat against hard-throwing Ewell Blackwell. As Blackwell started his windup, Restelli held up his hand, asked for time, and stepped out the batter’s box, and started cleaning his eyeglasses with the red bandana. Once finished, he raised his arm and gave Blackwell the I’m-ready-now sign. Murtaugh told a writer, “Blackwell glared at the naïve Pirate rookie and fired a [side-arm] fastball out of third baseman Grady Hatton’s uniform shirt.” The ball hit Restelli in the back of the neck. “He never knew what hit him,” said Murtaugh, “and he was never the same.” [20] Ralph Kiner’s recollection paralleled Murtaugh’s except that he thought the pitch hit Restelli in the shoulder, not the neck.[21] In 1975 Sports Illustrated writer Mark Kram espoused the same theory in an article on intimidation and fear in baseball. [22]

Game reports and notes from 1949 indicate that Blackwell hit Restelli in his first at-bat in the second game of a July Fourth doubleheader, the second time Restelli had been hit since joining the Pirates. Though he left the game, he doesn’t appear to have missed any additional time. The Pirates were off the next day, but Restelli remained in the starting lineup in the days following and went 6-for-21 with three doubles.

Restelli himself suggested that a botched tooth extraction contributed to his mid-July slump.[23] He said he lost 20 pounds and 50 percentage points off his batting average.[24] To his credit, he never missed a game as a result of the aforementioned maladies.

It probably isn’t too far off to say that all of these experiences and health-related issues contributed in reducing Restelli’s offensive production, some more than others. Although he had some good years in the Pacific Coast League after his brief tenure in Pittsburgh, he probably didn’t stay healthy long enough in any ensuing minor-league season to give major-league franchises the confidence they needed to give him another shot.

During the early stages of the 1950 season, Restelli experimented with contact lenses but appears to have returned to glasses later that same year. He failed to make the Pirates out of spring training and spent the season between Indianapolis (.161 with one home run in 21 games) and San Francisco (.340 with 17 home runs in 99 games).[25] In one hot streak reminiscent of his 1949 performance, he had eight consecutive hits for the Seals in two games against the Sacramento Solons.[26]

In 1951 Restelli made the Pirates out of spring training. After a week or two of limited duty, mostly pinch-hitting, Billy Meyer inserted him into the starting lineup. But after 38 at-bats, his average hovering below .200 with only one home run, Restelli was optioned to the Hollywood Stars in the PCL, where he batted .281 with 10 home runs in 76 games for the second-place Stars. He did not return to the major leagues again, and spent most of his remaining professional career in the Pacific Coast League.

After the 1951 season Restelli traveled to Japan with a group of players led by Lefty O’Doul, the San Francisco manager. O’Doul had been instrumental in passing on the skills and philosophy of American baseball in Japan and in promoting baseball in Japan with clinics and exhibitions. Besides Restelli O’Doul’s team included Joe DiMaggio, Dom DiMaggio, Ferris Fain, Bobby Shantz, Eddie Lopat, Mel Parnell, and George Strickland. The team played 35 exhibition games and some of the players visited US troops in Korea. [27]

Restelli put together occasional offensive bursts but seemed to falter physically for one reason or another, never again putting a good full season together. In September 1951 the Pirates sold his contract to the Washington Senators. Three months later the Senators sold him to the Cleveland Indians.[28] In 1952, after being released by the Indians, he hit .357 with seven home runs in 69 games for Sacramento of the PCL.[29] In 1953 he started the season with Portland and owned the highest batting average in the Pacific Coast League until early July, when a serious viral infection sent him to the hospital for 28 days. Doctors diagnosed an inflammation of the heart lining, and Restelli sat out the remainder of the season.[30]

In 1954 Restelli returned to Portland and hit .261 with 12 home runs in 117 games. After hitting well during the season’s early stages, he suffered a cracked shoulder in August when hit by a Cliff Chambers fastball. He may have incurred further injuries when he charged the mound and exchanged blows with Chambers, a former 1949 Pirates teammate. The umpires ejected both players. Restelli played another week before doctors discovered his broken shoulder.[31]

Restelli tried to come back with Portland in 1955 at the age of 31 but injuries suffered during the 1954 incident “left his throwing arm almost useless,” so Portland released him. He played briefly for Reno in the California League before calling it quits. He underwent surgery during the winter months in an effort to make a comeback. Reports circulated that he might come back with the Vancouver Mounties in 1956, but he never did.[32]

In 1958 Restelli joined the San Francisco Police Department. He told San Francisco reporter Jack McDonald he wanted to work with children in the juvenile bureau.[33] But shortly after hitting the streets of San Francisco, he severely injured his back trying to move a downed tree in a winter storm, effectively ending his law-enforcement career in San Francisco.

In a 1974 Baseball Digest “Whatever Became of . . . ” article, Bob Duvall wrote that Restelli was still single and managing an apartment complex in San Carlos, California. He wrote that Restelli had also been in the automotive accessory business.[34]

Restelli moved to San Carlos, California, about 20 miles south of San Francisco and an amateur-baseball hotbed in the late 1950s, to look after his parents, who by then had left San Francisco.[35] His father died in 1965 at the age of 68; his mother, whom his friends affectionately called Shorty, died in 1977 at 70. Sister Josephine died in 1997; brother Paulo died in 2007.

Though hampered by the back injury that forced him to leave the police department, Restelli recovered enough to occasionally take his hacks for at least one more year. He played occasionally and coached some semipro baseball in San Carlos. There he hooked up with former high-school teammate Hal Petrocchi. Petrocchi, a catcher, a three-time Galileo High School all-star, and a Yankee prospect until he injured his arm, managed and played for the San Carlo Merchants. The team’s business manager, John Ward, said he would “. . . never forget the tape-measure 3-run home run [Restelli] hit off Dave Turnbull at base hospital in Menlo Park.”[36]

Coaching the Merchants, Restelli gave Rick Lelo, then 17, some hitting advice, but Lelo found the recommended changes difficult to master and abandoned them. Three years later, in a bit of a hitting funk, Lelo remembered Restelli’s recommendations, implemented them, started hitting the long ball, and eventually signed with Minnesota.[37]

Restelli ran unsuccessfully for the San Carlos City Council but served 14 years on the city’s Parks and Recreation Commission, where he and others created an impressive multi-faceted program for children, teens, and adults. He also served on the Senior Citizens Advisory Board and in 1985 was president of the Old Timers Baseball Association of San Francisco. [38]

Restelli actively helped promote the former Seals baseball team, whether to benefit former teammates or promote youth-league baseball. Shortly before his death, though ill, he helped organize and attended a benefit for O’Doul, his first professional manager.[39]

Bill Soto-Castellanos, a batboy and clubhouse attendant at Seals Stadium in the early 1950s wrote in a memoir that when Restelli showed up at Seals Stadium as a member of the Hollywood Stars in 1951, “local fans loved him no matter which team he was on.[40]

“In my first day as visitors’ batboy with the Seals, Pittsburgh came to town [to play a couple of exhibition games] and Dino Restelli hit a homer that night [as the Pirates won, 14-5],” Soto-Castellanos wrote. “In the on-deck circle he talked with the fans. In 1954 when I was assigned the visitors’ clubhouse, Dino came to town with the Portland Beavers. [He] always had a good word to say. He even introduced me on one of the Seals Stadium Reunions. He was a gentleman in every sense of the word.”[41]

In the early ’60s Restelli joined a Bay Area swing dance group. Dance became his passion. By this time he was married and he and his wife, Jude, performed often in the San Carlos Chickens Ball, the longest-running school fundraising event in the United States (and probably the most successful, according to authors Nicholas A. and Betty S. Veronico).[42] He was the president of the Bay Swingers Dance Club in Oakland for several years and promoted West Coast Swing in the San Francisco Bay Area and at many dance conventions.[43] In 1994 he was inducted into the California Swing Dance Hall of Fame inducted Dino “as one whose outstanding talents and showmanship created a legacy of movement, rhythm, energy and style in the art of swing dancing.”[44]

Eventually Restelli was remembered more on the West Coast for his character and kindness than his modest home-run burst with Pittsburgh in 1949 or his 11-year career in the Pacific Coast League. Author Jack Heyde showed up at San Carlos home as an unannounced stranger in April 1999 hoping, but not expecting, to get some of his memorabilia signed. Restelli not only signed Heyde’s memorabilia but invited him in and gave him a signed photograph and directions to the home of another former major leaguer who lived nearby. “My visit with Dino Restelli,” Heyde said, “was one of those totally unexpected pleasures that everyone experiences on occasion. From an initial concern and uncertainty over what to expect at Dino’s somewhat foreboding residence came one of the most enjoyable and rewarding visits that I have made.”[45]

Restelli jump-started his baseball career again in 1986 when at the age of 62 he learned that Lick-Wilmerding High School, a prep school in San Francisco, needed a baseball coach. The school had not fielded a competitive baseball team in several years. Peter Dalton, an athletic director and baseball coach at another San Francisco high school, and a member of the San Francisco Old Timers Baseball Association, urged Restelli to the job and contacted the school on Dino’s behalf. Jude Restelli recalled that the team was young and inexperienced, so before the first game Dino concentrated on perfecting their bunting skills. In an early-season game against a strong team he convinced his players that a bunt-based offense might surprise the opposition. The opponents apparently hadn’t worked on their bunt defense and couldn’t handle the onslaught of bunts. Dino’s team bunted with no outs, one out, and even two outs, and won the game. Restelli coached the team for five more years. His players said they loved his enthusiasm for the game, low-key demeanor, and quiet confidence. And they respected his professional experience and knowledge of the game.[46]

Dino Restelli died at his San Carlos home on August 8, 2006. At his funeral Mass in San Carlos, Jude Restelli led mourners in a quiet rendition of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.”

Kurt Houtkooper, who played for Dino at Lick-Wilmerding from 1987-1990 and then went on to play at Laney College in Oakland and at the University of California, remembered his former mentor as “very giving to all the student athletes at Lick, very giving with his time and with his experience and knowledge,” and said, “The players loved playing for Dino. Spending time with Dino meant you also spent time with Jude, his wife. She showed up to every game, [kept score] at the games and was our loudest cheerleader. If we had an assistant, it was Jude. Not for sports, but for life. The love they expressed for each other was a great life lesson for all the players.”

Former Los Angeles Dodgers general manager Fred Claire said it best: “Dino Restelli wasn’t a one-year wonder, as he is recalled by some. He was a man who lived 81 full years, as recalled by many.”[47]

June 25, 2011

Sources

Finoli, David, and Bill Rainier. The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2003.

Heyde, Jack. Pop Flies and Line Drives. Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing, 2004.

Kelley, Brent P. The San Francisco Seals, 1946-1957. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 2002.

McCollister, John. Tales From the Pirate Dugout. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2003.

Moffi, Larry. This Side of Cooperstown. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1996.

Polk’s Crocker-Langley San Francisco City Directory. San Francisco: R.L. Polk & Co. (1942-1960).

Soto-Castellanos, Bill. 16th & Bryant: My Life & Education with the San Francisco Seals. Pinole, California: Clubhouse Publishing, 2007.

Veronico, Nicholas A. & Betty S. Images of America: San Carlos. San Francisco: Arcadia Publishing, 2007.

Voigt, David Q. American Baseball From Postwar Expansion to the Electronic Age. University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State Press, 1983.

Wells, Donald R. Baseball’s Western Front: The Pacific Coast League During WWII. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 2004.

www.baseball-reference.com

In addition, thanks to Lissa Crider (Lick-Wilmerding High School librarian), Lisa Petrocchi (Hal Petrocchi’s daughter), Carl Nolte (San Francisco Chronicle), Sheila Conway (Santa Clara University Library), John Ward (San Francisco area amateur baseball historian), Glynis Asu (Hamilton College librarian), Donna Sylvestri (daughter of former Seal and White Sox player Marino Pieretti), and Tim Wiles (National Baseball Hall of Fame Research Center).

[1] “Sport: Bumper Crop,” Time, July 14, 1949.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Spink, J.G. Taylor, The Sporting News, July 6, 1949.

[4] Biederman, Les, The Sporting News, August 3, 1949.

[5] San Francisco Chronicle, August 13, 2006.

[6] Miller, Hub, ”Restelli, Another O’Doul Protégé, Baseball magazine, November 1949.

[7]Ibid.

[8] “Baseball All Stars (1939 -1945),” San Francisco Chronicle (source) for online site: Bay Area Sports Stars, May 31, 1942.

[9] John Ward Collection, Galileo yearbook articles concerning the Galileo baseball team 1941-1943.

[10] Stevens, Bob, “This is Jerry Coleman: Ever a Yankee,” Baseball Digest, January 1950.

[11] Smith, Red, “Fun Games and War,” Views of Sport: New York Herald Tribune, 1954.

[12] Several sources, including Restelli’s obituary, indicate that he attended Santa Clara University; however, the university has no record of him registering and the athletic department does not list him as one of its major-league alumni. Additionally, his wife said she didn’t think he ever attended though he might have at one point intended to register and attend.

[13] Miller.

[14] San Francisco area induction records; news articles from Restelli’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame Research Center report he served in the South Pacific.

[15] The Sporting News, June 22, 1949. Gregg remained the property of the Pirates on option to San Francisco, which had no major-league affiliation in 1949.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Restelli, Dino, “Restelli Credits Success to O’Doul,” New York Journal-American, August 21, 1949.

[18] It seems as though everyone had an opinion as to the reason for Restelli’s inability to continue at his blistering early-season pace.

[19] The Sporting News, July 6, 1949.

[20] Baseball Digest, September 1964: 76.

[21] Koppett, Leonard, Sports of The Times, New York Times, July 26, 1967.

[22] Kram, Mark,”Their Lives Are On The Line,” Sports Illustrated, August 18, 1975. (Kram’s professional baseball career ended when a minor-league pitcher hit him in the head.)

[23] Pacific Stars & Stripes, February 16, 1950.

[24] You have to wonder, though, if Pittsburgh management might have been blinded by Restelli’s falling batting average in 1949 and benched him too early – especially since the Pirates had fallen out of the pennant race, and he had suffered through illness and injury. His on-base average was a respectable .358 and his on-base plus slugging average (OPS) was.811, just a few percentage points lower than outfield partner Wally Westlake (.815). Restelli didn’t strike out all that much for a power hitter, so you have to think balls would have eventually started dropping for him and he would have regained his power stroke. His replacement, Tom Saffell, also a rookie, hit well (.322/.385/.395) but Saffell, too, crashed and burned in 1950, finishing his four-year career with an OPS of .602.

[25] I found nothing to suggest Restelli had trouble adjusting to wearing contact lenses, though this may very well have been the case. News articles suggest that he intended to start wearing contact lenses in 1950, but he didn’t even make the Pirates roster out of spring training, instead being sent to Indianapolis, where he struggled. He eventually was optioned back to San Francisco, where he performed rather well. Later articles often referred to him as the “bespectacled outfielder,” so he appears to have started wearing glasses again after 1950.

[26] The Sporting News, August 9, 1950.

[27] Moffi, Larry. This Side of Cooperstown, 144-145.

[28] Dino Restelli Trades and Transactions, baseball-almanac.com..

[29] Cleveland optioned Restelli to Indianapolis. Indianapolis released him; he later signed with Sacramento (no major league affiliation). In 1953 he signed with Portland (no major league affiliation).

[30] Pacific Stars & Stripes, August 3, 1953.

[31] Since Restelli was a right-handed hitter, the pitch likely hit him in the left shoulder; he may have injured his right shoulder and throwing arm in the ensuing fistfight.

[32] The Sporting News, March 28, 1956.

[33] McDonald, Jack, “Restelli, Ex-Buc, Now Crack Shot and Judo Whiz as Frisco Bluecoat,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1958.

[34] Duvall, Robert, “Whatever Became of …” Baseball Digest, February 1974: 86. Beyond what is mentioned in this article, I could not locate specific details of Restelli’s employment history after baseball and his short stint in law enforcement. Dino and Jude were married in 1969. They had no children of their own, but she brought a 7-year-old daughter, Lesley, into their marriage.

[35] Paul and Angella Restelli disappear from the San Francisco Polk Directory in 1959 and show up in the San Mateo County Telephone book in San Carlos in 1961.

[36] E-mail from former business manager John Ward, December 2010. I located the box score from this game played in 1959 on goodoldsandlotday.com. Dave Turnbull, a local prep star at Carlmont High School in Belmont, would have just graduated after leading Carlmont to the South Peninsula Athletic League title. Turnbull later played in the Baltimore organization, advancing to Triple-A before retiring. The newspaper account reports Restelli’s drive to have been over 400 feet. The term “tape measure” was often used by those discussing his home runs.

[37] Rick Lelo e-mails.

[38] Telephone conversation and e-mails with Peter Dalton, a past president of the Old Timers Baseball Association of San Francisco. Additionally, a list of former presidents of the association was posted on the the association’s website in February 2009.

[39] Claire, Fred, “Dino Restelli, Baseball Perspectives.” MLB.com, August 2006.

[40] Soto-Castellanos, Bill. 16th & Bryant.: My Life & Education with the San Francisco Seals, 47.

[41] Legacy.com, August 13, 2006.

[42] Veronico, Nicholas A., and Betty S. Veronico. Images of America: San Carlos (San Francisco: Arcadia Publishing, 2007), 87.

[43] Michelle Kincaide (www.michelledance.com/memorials.htm).

[44] Raper’s Who’s Who in Swing Dance (www.whoswhoinswingdance.com).

[45] Heyde, Jack. Pop Flies and Line Drives, 74.

[46] Telephone conversations or e-mails with Jude Restelli and former Lick-Wilmerding players Kurt Houtkooper, John Pitts III, and Jean-Luc Chiromberro, August 2010-April 2011.

[47] Claire, op. cit.

Full Name

Dino Paolo Restelli

Born

September 23, 1924 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

August 8, 2006 at San Carlos, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.