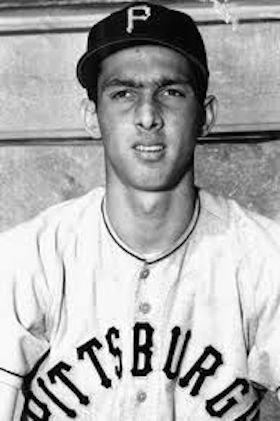

Ron Necciai

Ron Necciai is the real-life Sidd Finch, the greatest pitcher who never was.1 The right-hander struck out 27 batters in a nine-inning game when he was 19. The National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, the governing body of the minors, called it “the greatest individual performance in the history of baseball.”2

Ron Necciai is the real-life Sidd Finch, the greatest pitcher who never was.1 The right-hander struck out 27 batters in a nine-inning game when he was 19. The National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, the governing body of the minors, called it “the greatest individual performance in the history of baseball.”2

Instead of walking away like the mythical Finch, Necciai was forced out by injury and illness. He retired at 22. “One sore arm and it lasted forever,” he said.3

“The greatest all around pitcher I ever saw never was a major league regular,” Branch Rickey said. “He had the best fastball; he had all the learning aptitudes; he was great. He was Ron Necciai from Monongahela.”4 Rickey claimed Necciai rivaled Christy Mathewson and Dizzy Dean.

“There are has-beens and never-wases,” Necciai said once. “I’m a might-have-been. I lived a lifetime in one night.”5 But Necciai was no one-game wonder. His 1952 minor-league season stands as one of the most dominant ever.

The game that made Ron Necciai famous for life took place on May 13, 1952, in Bristol, actually a pair of scruffy Appalachian towns straddling the state line separating Tennessee and Virginia. The singer Tennessee Ernie Ford, who was born there, said if he had lived on the other side of State Street he would have been called Virginia Virgil.

The little local ballpark, on the Virginia side, was named, grandiosely, Shaw Stadium. It was home to the Bristol Twins, a Pittsburgh farm club in the Class D Appalachian League. Necciai was there because of the Twins manager, George Detore, a former big-league infielder and minor-league lifer. Necciai’s father had died before the boy was 5; Detore was his surrogate dad, and Necciai had asked the Pirates to send him to Detore for a third season.

Necciai was still learning to pitch. When he was in high school, one of his fastballs broke a batter’s ribs, and he played mostly first base from then on, until Detore put him on the mound in his first professional season. Detore gave him a game plan for every start and called some pitches from the bench. Most important, Detore kept him calm, pumped up his confidence, soothed his worried mind.

Necciai told people, “I worry about everything.”6 During spring training in 1952, he couldn’t keep food down and started vomiting blood. A doctor diagnosed stomach ulcers and warned him, “It’s not what you’re eating, it’s what’s eating you.”7 Necciai was 6-foot-5 according to the newspapers, 6-3 by his own recollection, and probably weighed less than 150 pounds by the time he went to the doctor. He was all arms and legs and ears and nose, a gawky Italian kid from Pennsylvania’s Monongahela Valley, smoke-choked coal and steel country near Pittsburgh.

Ronald Andrew Necciai was born in Gallatin, Pennsylvania, on June 18, 1932, the third of four children of the former Anna Gondoly and Attilio Necciai (pronounced NETCH-eye), both first-generation Americans. After Attilio, a steel mill worker, died of pneumonia at 31, Anna struggled to provide for her family. She worked in a mill and cleaned houses, and the children got after-school jobs. Ron caddied at a country club and swept up in local stores. “My mother, she was my hero,” he said.8

He played center on the Monongahela High basketball team, end and place kicker in football, and soccer as well. Tony Rockino, a barber at Pittsburgh’s Schenley Hotel, across the street from Forbes Field, spotted him playing baseball and recommended him to the Pirates. Necciai signed right after high school graduation in 1950, shortly before his 18th birthday. No bonus, just $150 a month. “In those days, anything beat working in the mill,” he said.9 (Branch Rickey had nothing to do with signing Necciai; Rickey didn’t arrive in Pittsburgh until November.)

Necciai signed as a first baseman, but Pirates scouts had seen him zinging the ball around the infield. When he reported to the Class D farm club in Salisbury, North Carolina, manager Detore informed him he was a pitcher. Necciai did what he was told, but he didn’t know what he was doing. In his first two professional games he gave up seven runs and walked six in three innings. He was transferred to another Class D team in Shelby, North Carolina, where he pitched once, surrendering three runs without getting anybody out.

Failure and homesickness overwhelmed him. He quit after two weeks. “Baseball was never really a passion of mine,” he explained decades later. “To be honest, I never did have any passions. Baseball was just something to do. I was just an average kid drifting through, and it didn’t seem to make much sense to stay.”10

Necciai moved back in with his mother and stepfather and went to work in an auto parts plant, but the scout who had signed him, Charlie Muse, kept pestering him to give the game — and himself — another chance. The factory job reminded him why he had gone into baseball in the first place. After his humiliation in North Carolina, he found it hard to believe that the Pirates wanted him, but anything beat the mill.

He went to spring training in Deland, Florida, in 1951 — that beat a Pennsylvania winter — and Rickey saw him for the first time. Radar guns did not yet exist, so there was no way to know how hard Necciai was throwing. It was hard enough to impress Rickey, who had seen practically every fireballer since Cy Young.

Sending Necciai back to George Detore in Salisbury, Rickey told Detore to have the young beanpole throw his fastball sidearm, using his long arms to intimidate right-handed batters. Detore also taught him the diving overhand curve that Rickey and his disciples taught to generations of pitchers. But the fastball often sailed over batters’ heads, and the curve skipped in the dirt.

Necciai’s early-season games in Salisbury looked like more of the same. He lost seven straight decisions while walking everybody but the peanut vendor. He told Detore he was going home. The manager convinced him to stay by offering him an extra $90 a month to drive the team bus.

Detore didn’t think he was cutting loose and demanded, “Chrissakes, son! Can’t you throw any harder than that?” Necciai explained about the boy whose ribs he had broken in high school. Detore told him, in effect, This ain’t high school.11 His livelihood was on the line.

Branch Rickey Jr., the Pirates farm director, also chewed him out. With his great stuff, Rickey said, there was no excuse for all the losing. Necciai then won four in a row. Even though he had walked 87 in 106 innings, the Pirates jumped him from Class D to Double A ball in New Orleans.

In his New Orleans debut on July 29, the 19-year-old pitched a strong seven-inning complete game, allowing just two runs on five hits, but lost when his teammates failed to score. The rest of Necciai’s season went straight downhill. Double A hitters hammered him for 33 runs in his next 26 innings. He finished with a 1-5 record and 8.45 ERA in the Southern Association.

Still, the Pirates took him to their fall school for top prospects in Florida. As Rickey Jr. recalled it, Necciai walked the first two men he faced, beaned the third one, and hit the fourth. Then he started missing batters and bats. “We knew it was only a question of time with this boy,” Rickey Sr. said. “He had all the raw ability any pitcher ever had.”12

Necciai was surprised to be invited to the major-league spring training camp in San Bernardino, California, in 1952. He pitched five shutout innings against the defending National League champion Giants. Although he looked overmatched in some other outings, allowing seven runs in 10 innings, and had had little success in the minors, Rickey and manager Billy Meyer planned to let Necciai start the season on the big-league roster.

All spring Necciai had been losing weight because he couldn’t eat. His nervous nonstop smoking didn’t help. When he began spitting up blood, Rickey sent him to Pittsburgh to see the team physician. Dr. Norman C. Ochsenhirt prescribed banthine, ulcer pills known generically as propantheline bromide, and put him on a soft diet: no fried food, no dry cereal, and only strained fruit and vegetables. Necciai spent time in a hospital and rested for two weeks. Since he needed to work himself into shape, he asked to go to Bristol with Detore.

After seeing Necciai’s fastball in spring training, Bristol Herald Courier sports editor Gene Thompson began calling him “Rocket Ron.” The rocket launched on Opening Night before about 2,400 at Shaw Stadium. Necciai struck out 20 Kingsport Cherokees and shut them out on two hits. Just as encouraging, he walked only four. Thompson wrote, “Necciai’s new 20-game strikeout record for a Bristol pitcher should stand for a long time — unless he breaks it himself before he leaves.”13

In his next start the Pulaski Phillies touched him for two runs in the first, but he chalked up 19 strikeouts and hung on for a 7–4 victory. Three days later Detore used him in relief; he struck out 11 of 12 batters and saved a 5–4 win.

Necciai’s teammates called him “Necktie,” not just because of his name; he looked like a skinny necktie. He, catcher Harry Dunlop, and outfielder Bob Chrisley rented $5-a-week rooms in a widow’s home. Dunlop, Necciai’s closest friend on the team, was a baby-faced 18-year-old beginning a career that would stretch into the 21st century, including more than 20 years as a major-league coach.

“Of all the pitchers I’ve seen in 50 years in the game, he threw harder than any of them,” Dunlop said. “Some fastballs are heavy, and you feel like the pitcher is throwing an eight-pound shot. Ron’s fastball was light and it had rise on it. His curveball was almost equivalent to a split-finger nowadays. It had an old-style drop, with variations to one side or the other depending on the amount of finger pressure.”14

Even with his spectacular performance, Necciai was suffering. His burning stomach kept him awake nights. A small Southern town offered few menu choices for someone who couldn’t eat fried food. He subsisted on Melba toast, boiled eggs, cottage cheese, and cheese sandwiches, along with the black banthine pills.

Necciai barely slept the night before his May 13 start, and left most of his cheese sandwich on the plate at lunch in the players’ favorite diner. When he got to the ballpark, Detore could see he wasn’t right: “[H]is ulcers were really kicking up badly, so I told him to go to the club house and I would start some one [sic] else.”15 Necciai swallowed a couple of pills and rested awhile, then told the manager he’d give it a shot.

On a damp, chilly Tuesday evening, Shaw Stadium was less than half full, with 1,183 on hand, when Necciai faced the Miners from Welch, West Virginia.

First inning: strikeout, strikeout, strikeout. The last strike three got away from Dunlop, but he threw the batter out at first.

Second inning: strikeout, groundout to shortstop, strikeout.

Third inning: The first batter was safe on an error when Bristol’s shortstop, Don DeVeau, fumbled a ground ball, then strikeout, strikeout, strikeout.

Fourth inning: Necciai hit the leadoff batter, then strikeout, strikeout, strikeout.

As he racked up Ks, Necciai’s stomach was rebelling. Detore remembered him throwing up in the dugout, but Necciai never mentioned that. At one point Detore sent the bat boy to the mound with two pills and a glass of milk, and the game halted while the pitcher tried to douse the flames inside. Detore also sent a pitcher and catcher to the bullpen in case Necciai couldn’t finish.

Fifth inning: strikeout, strikeout, strikeout.

Welch’s Frank Sliwka, who was on deck to pinch-hit when the top of the fifth ended, thought Necciai could have beaten a big-league team that night, the way his curve was dropping: “I’m not talking four or five inches. I’m talking a foot.”16

Sixth inning: strikeout, strikeout, strikeout.

“In about the sixth inning the fans began chanting numbers. 16! 17! 18!” Dunlop recalled. “I came into the dugout and I asked, ‘What are all the numbers about?’ They told me he was striking out everybody. And I thought I better start bearing down.”17

Seventh inning; 18, 19 (11 straight), base on balls, 20.

After seven, Bristol had run up a 7–0 lead. “We knew Ron was having strikeouts galore but essentially we were thinking of the no-hitter,” first baseman Phil Filiatrault said. “As the game progressed it became more pressure-filled.”18 Of course, none of the Twins would say a word to their pitcher.

Eighth inning: 21, 22, 23.

Detore said, “The last two innings the Welch club was just trying to bunt the ball to keep from striking out.”19 Only two batters had put a ball in play; bunting didn’t work any better.

Ninth inning: Leading off, pinch-hitter Frank Whitehead lifted a pop foul between home and first. As Dunlop went after it, first baseman Filiatrault called, “Drop it, drop it!” The crowd picked up the chant and the ball fell untouched. “Harry let it fall,” Filiatrault said years later, but Dunlop and Necciai insisted that was not so. They blamed the dim lights.20 The scorer wrote down “E-2.”

Whitehead was called out on strikes. Another pinch-hitter, Joe Uram, fanned, Necciai’s 25th victim. When sportswriters searched the record books after the game, they found that Hooks Iott had struck out 25 for Paragould, Arkansas, in 1941; that was accepted as the record for a nine-inning professional game.

With two away, Welch center fielder Billy Hammond became the record-breaking number 26, flailing at a curve that bounced on the plate. But the ball got past Dunlop for a wild pitch that skittered to the backstop while Hammond raced to first, Welch’s fourth base runner.

Another conspiracy theory: Some of the players believed Dunlop had let it get by him to give Necciai a chance at 27. The catcher said no way: “He had a great curveball, an old fashioned drop. A lot of them dropped in the dirt. He wasn’t easy to handle.”21 That Sandy Koufax curve, the 12-to-6 knee-buckler, was what made him so dominant. Inexperienced hitters had never seen anything like it.

Welch cleanup hitter Bob Kendrick was next. “Necciai was humming the ball,” he recalled. “By the time you saw the ball under those minor league lights it was too late.”22 Kendrick thought he might have fouled off a pitch or two before he became number 27.

Necciai remembered few of these details. He didn’t know any of the Welch players, how many fanned or how many were called out (17 swinging, 10 called).23 When his teammates told him what he had done, he thought it surely must have happened before in more than a century of baseball.

No sportswriter interviewed the pitcher after the game; writers didn’t collect postgame quotes then. The Herald Courier reporter, Jimmy Carson, hurried back to the newsroom and sent the story to the Associated Press for nationwide distribution. AP’s state editor in Richmond, the future television anchor Paul Duke, read “27 strikeouts” and called to ask if the boys in Bristol were drunk.24

As he relived the game over and over for decades, Necciai played down his accomplishment. He recalled bouncing curveballs and falling behind hitters. Dunlop didn’t remember a single three-pitch strikeout. “It wasn’t a perfect game,” Necciai said. “There were guys on base. It wasn’t until the next morning, the phone started ringing, we realized it had never been done before.”25

Reporters from all over the country called, clamoring to interview the new strikeout king. The Ed Sullivan Show, CBS-TV’s Sunday night variety extravaganza, invited him to appear, but the Pirates said no. Necciai didn’t want to go, anyway. People who met him in Bristol remembered him as a polite boy who handled the sudden onslaught of fame with grace.

Necciai pitched twice more for Bristol. Coming on in relief, he struck out the first eight men he faced, including five in one inning when two batters reached base on wild third strikes.

His final start came on Ron Necciai Night, May 21. Fans loaded him down with gifts, but the most memorable are the ones Necciai handed out: for Detore, a watch inscribed “To the man who made it possible”; for each teammate, a fountain pen with the inscription “We did it on May 13.”26 At the end of the ceremony, Necciai’s mother walked onto the field to surprise him.

In that night’s game against Kingsport, he struck out 24 and allowed only two hits for his third shutout in four starts. Branch Rickey Jr., who was watching, said, “It would be criminal to leave that boy in this league; he’s too good for Class D. He has the hitters intimidated. He ties them in knots with that curve ball, then handcuffs them with his speed.”27

Even in the strikeout-happy baseball of a later generation, Neccai’s totals with Bristol look like Little League numbers. In six games he struck out 109 in 42 2/3 innings — almost 23 per nine innings.28 True, he rang them up against Class D hitters under feeble lights, but no pitcher has ever come close at any level of professional ball.29 Necciai walked 20 and allowed two earned runs on 10 hits for a 0.42 ERA. The batters were helpless.

Two months earlier the Pirates had been eager to rush Necciai to the majors. Now they turned cautious and promoted him only to Class B Burlington-Graham in the Carolina League.30 He detoured to Pittsburgh to see the team doctor about his ulcers. While he was there the Pirates showed him off in a workout at Forbes Field. “He can throw as hard as anybody in this league,” catcher Joe Garagiola said. “He can throw as hard as Feller if he wants to. He could be the answer to our prayers.”31 The club was buried in last place.

George Detore said, “Give that kid a month with Burlington and the whole league’ll have ulcers.”32 In a little more than two months Necciai proved Detore right. Class B hitters were not as intimidated, but they weren’t much more successful. Pitching in 18 games and 126⅓ innings, Necciai struck out 172 — 12.26 per nine innings. Nearly as impressive, given his history as a wild thing, he struck out almost three times as many as he walked.33

With Dunlop as his catcher, he had three 14-stikeout games, one of them on his 20th birthday. Two pretty girls brought a cake onto the field. Neccciai fanned 12 in three other starts and 16 in a 14-inning loss. He saved the best for last. On August 2 he struck out 17, retiring the last 16 Class B batters he faced, in a three-hit shutout.

It was time. The Pirates called him up on August 6. The club was enduring a historically awful season; that day they dropped a doubleheader to fall 42 games out of first place.

The front office built up the strikeout king’s first start as if he were in fact the savior. The biggest crowd of the season, more than 17,000, saw his debut against the Cubs on August 10 in the opener of a Sunday doubleheader. The lucky fans were those who arrived late and missed the first-inning massacre. Single, single, double, RBI fly out, walk, stolen base, intentional walk, single, double. Chicago scored five times before Necciai got the third out. Garagiola said, “He was shaking so bad out on the mound, he couldn’t see my signals.”34 After yielding seven runs, Necciai rallied to finish with three scoreless innings before leaving for a pinch-hitter in the sixth.

Manager Billy Meyer ran him back out in relief the next night, and he worked three scoreless, hitless innings against Cincinnati, striking out five. The only base runner reached on a wild third strike. That was more like it.

For the rest of the season Necciai pitched like the typical rookie, inconsistently, with more bad games than good. After the Cardinals knocked him out in his second start, Stan Musial asked to meet the phenom. Musial came from Donora, Pennsylvania, the next town over from Monongahela. “Throw strikes, kid,” the Man told him. “You’ve got to throw strikes if you want to stay up here.”35

Necciai notched his only victory on August 24, when he held the Boston Braves to three runs (one unearned) and seven hits over eight innings. Murry Dickson pitched the ninth, and Necciai got him to sign the game ball. It was the only souvenir he kept from his brief big-league career.

In the season’s final game, Necciai pitched seven strong innings against Cincinnati and left with no decision as the Pirates lost for the 112th time. He had worked 54⅔ innings in nine starts and three relief appearances, striking out 31 (a rate better than average for the NL that year) while walking 32. A 1-6 record and 7.08 ERA is his only line in the major-league encyclopedias.

With Bristol, Burlington, and Pittsburgh, Necciai pitched 230⅔ innings, up from 139 the previous year. By modern standards, it was horrible abuse of a 20-year-old pitcher, not to mention a sickly one.

Then the army abused him some more. Despite his medical history, Necciai was drafted in January 1953. He spent 65 days in the service, a substantial number of them in the hospital at Fort Knox, Kentucky, after he passed out one night. He said he couldn’t get the ulcer pills he needed. He lost about 30 pounds in the two months. “I was a walking pile of bones,” he said. “I never hated anything in my life as much as I hated the army.”36

Necciai received a medical discharge on March 19. Still weak, he began working out at Forbes Field instead of joining the Pirates in spring training. One day he felt a pop in his shoulder. It was the end. “The muscles were torn, and I was through that winter, although I didn’t know it.”37

He didn’t pitch until Memorial Day. Back in Burlington, he struck out 13 in his first start, but lasted little more than a month. A doctor at Duke University diagnosed a pinched nerve and told him to shut down for the rest of the season.

Some Pirates executives and even some doctors thought the problem was in his head. That’s what they said rather than admit they couldn’t figure out what was wrong. X-rays didn’t show anything, and X-rays were all they had. He’s 21 years old, big as a horse. Has to be in his head.

In a December 1953 interview Branch Rickey voiced a Christmas wish for “a normal Ron Necciai…. He is a second Dizzy Dean in my estimation.”38 Right after Christmas the Pirates dropped him from their roster and sent him to Waco of the Big State League, Class B.

He tried a comeback in 1954, another in 1955, around visits to the Mayo Clinic and Johns Hopkins. “They shoot you up with cortisone pretty good and you’re able to throw for a half hour, but then you can’t wipe your tail for a few weeks,” he said.39 “Finally one doctor at Johns Hopkins told me to quit baseball and go find a job in a gas station.”40 Necciai won one last game for Waco in May 1955, then gave up. He was not yet 23.

“It was tough to accept at the time,” he said. “You look around and you think, ‘My God, can’t they heal me?’ Young people heal.”41

Necciai had married a hometown girl, Martha Belle Myers, in February 1955. He worked in her father’s hardware and sporting goods store, played first base for a sandlot team, and joined a winter basketball team with several Pirates. He remained bitter at his treatment by the Pittsburgh club and the minor league teams that, he believed, had exploited him to sell tickets.

Within a few years he got a job with a sports equipment company, demonstrating fishing and hunting gear at outdoor shows. Then he became part-owner of an equipment distributorship, Hays, Necciai and Associates. As a prosperous businessman in Monongahela, he served on the school board and drove a Cadillac with the license tag “NECTIE.” Ron and Martha raised a daughter and two sons, and bought a winter home in Florida.

The ulcers disappeared, and Necciai ballooned to 260 pounds in middle age. “Isn’t it funny?” he told the writer Pat Jordan. “I can eat anything now. The hotter and the spicier the better.”42 He still couldn’t throw a baseball without pain; when he was around 70 a doctor told him he had a torn rotator cuff — he’d never heard that before — and he had surgery to repair it.

Necciai’s bitterness faded with time. He recognized that his baseball fame had helped him in business. Many times he said, “I gave baseball a nickel and got a million dollars back.”43

Thirty years after the game that made him famous, Necciai had a reunion dinner with Harry Dunlop, who was a coach for Cincinnati. He returned to Bristol the next year to throw the ceremonial first pitch on Opening Day in the town’s new ballpark. He went back in 1999 to unveil a plaque at DeVault Stadium commemorating his feat. Through all the decades he patiently repeated the story of his glorious moment and the pain that followed for any sportswriter who asked.

The Necciais retired to Florida’s Gulf Coast. On March 3, 2016, the mayor of Bradenton proclaimed Ron Necciai Day and the white-haired 83-year-old original Rocket threw out the first pitch at a Pirates exhibition game. He bounced it in the dirt. Must have been his curveball.44

Last revised: May 11, 2016

Additional Sources

Burlington (North Carolina) Daily News, 1952.

Greensboro (North Carolina) Daily News, 1952.

The Sporting News

Notes

1 Sidd Finch, a Buddhist right-hander with a 168-mile-an-hour fastball, was the invention of writer George Plimpton. “The Curious Case of Sidd Finch,” Sports Illustrated, April 1, 1985. Note the publication date.

2 Bruce Wald, “Monongahela’s Necciai earns state hall of fame induction,” triblive.com, June 7, 2014. http://triblive.com/neighborhoods/yourmonvalley/yourmonvalleymore/6183841-74/hall-necciai-fame, accessed April 15, 2016.

3 Pat Jordan, “Kid K,” Sports Illustrated, June 1, 1987. http://www.si.com/vault/1987/06/01/115475/kid-k-in-1952-ron-necciai-19-struck-out-27-batters-in-nine-innings-the-three-greatest-pitchers-branch-rickey-had-known—-were-christy-mathewson—-dizzy-dean—-and-ron-necciai, accessed April 14, 2016.

4 Jimmy Jordan, “Rickey Pays Tribute to Wallace, Necciai,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 25, 1959: 27.

5 Paul Jayes, “A Moment of Glory He’ll Never Forget,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 19, 1983: 19.

6 Steve Buckley, “Rocket Ronnie’s Moment in the Sun,” Collector’s Sportsbook, April 1994, 36.

7 Pat Jordan, “Kid K.”

8 George Stone, Rocket Ron (Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Infinity, 2008). Stone’s interviews with Necciai’s teammates and opposing players in the 27-strikeout game are invaluable.

9 Jayes, 19.

10 Pat Jordan, “Kid K.”

11 Pat Jordan, “Kid K.”

12 Les Biederman, “Strikeout Story,” Complete Baseball, September 1952, 61.

13 Quoted in Stone, 75.

14 Kevin T. Czerwinski, “‘Rocket’ Ron Recalls 27-K Game in Appy League,” milb.com, August 23, 2006. http://www.milb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20060819&content_id=120279&vkey=news_milb&fext=.jsp, accessed April 16, 2016.

15 George Detore memo to Jim Ford, June 9, 1969, in Necciai’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

16 Stone, 104.

17 Jerome Holtzman, “Remembering Rocket Ron,” mlb.com, June 15, 2000.

18 Holtzman.

19 Detore memo.

20 Holtzman.

21 Holtzman.

22 Stone, 119.

23 A scoresheet from the game is in Necciai’s HOF file. It is unsigned, but appears to be that of official scorer Richard Snapp. Other details of the game come from Stone, Rocket Ron, and Detore’s memo.

24 Stone, 127-129.

25 Jayes, 17.

26 David Condon, “Failure Against Cubs Starts Rocket Ron on Road Back!” Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1952: E3.

27 “Strikeout Artist Too Good for Class D, Says Rickey Jr.,” Associated Press-Baltimore Sun, May 23, 1952: 23.

28 The Bristol stats are based on contemporary newspaper stories. Baseball encyclopedias erroneously give him 43 innings pitched.

29 Of course, you’re wondering about Steve Dalkowski. The legendary left-hander struck out 17.6 per nine innings in 62 innings for Kingsport in 1957, and the same in 1958 in 62 innings for Aberdeen and in 42 innings for Knoxville. Each time he walked at least 16 per nine innings. No one else appears to have come close to Necciai, but strikeout records from the low minors are incomplete.

30 The North Carolina towns are side by side. Burlington was much larger, but the ballpark was in Graham.

31 Pat Jordan, “Kid K.”

32 Condon, “Ron Suffers from Ulcers but Gives Foes Headaches” Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1952: B3.

33 The Burlington stats come from contemporary newspaper game accounts and box scores. Baseball encyclopedias erroneously give him 126 innings pitched.

34 Pat Jordan, “Kid K.”

35 Thomas K. Perry, “Ron Necciai, the Man Who Struck Out Everybody,” Blue Ridge Country, March/April 1999, 40.

36 Buckley, 38.

37 Jimmy Jordan, “Rickey Pays Tribute,” 26.

38 Jack Hernon, “Rickey Clan, Size of a Ball Club, Holds Christmas Reunion Today at Branch’s,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 25, 1953: 28.

39 Czerwinski.

40 David Assad, “Necciai Whiffed 27 in 1952 Class D Game,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 3, 1994: W-10.

41 Jayes, 19.

42 Pat Jordan, “Kid K.”

43 Stone, 185.

44 http://www.bradenton.com/sports/mlb/pittsburgh-pirates/article64154957.html, accessed April 16, 2016.

Full Name

Ronald Andrew Necciai

Born

June 18, 1932 at Gallatin, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.