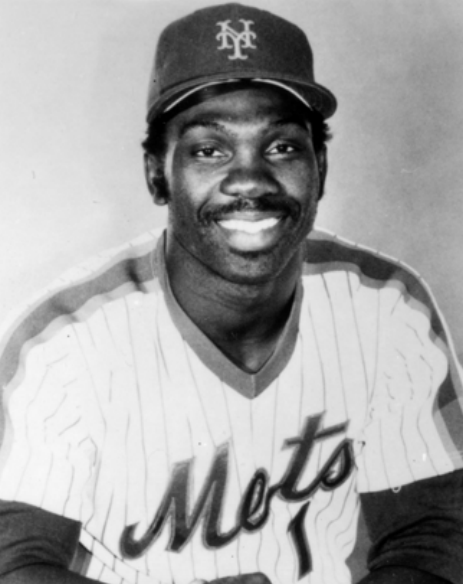

Mookie Wilson

Mookie Wilson stood at the plate in the bottom of the 10th inning, arcing his bat, focusing intently on Red Sox pitcher Bob Stanley. He realized that he represented the potential winning run in the most important game of his life and he was determined not to make the final out. Wilson had come a long way in his relatively short major-league career: toiling for the New York Mets various farm teams; named the starting center fielder for the laughable big-league club; subsequently becoming the consensus face of their organization, all within six rapidly-moving seasons. He was 30 years old and he had already seen a lot…

William Hayward Wilson was born in Bamberg, South Carolina, on February 9, 1956, one of 12 children. Two of his brothers also played pro ball for a short time: John was drafted by the Mets and stole 56 bases for Columbia in the South Atlantic League in 1984; Phil played in the minors for the Minnesota and Montreal organizations, while a third brother, Richard, probably played the biggest role in his family life a number of years later.

Nicknamed Mookie as a child because of the way he asked for milk (or so the legend goes), Wilson pitched for Bamberg-Ehrhardt High School under coach Dave Horton, the local legend who became the first high-school baseball coach inducted into the South Carolina Athletic Hall of Fame. Wilson’s years there included a state championship (one of 14 won by Horton.) After leaving Bamberg-Erhardt, Wilson signed a letter of intent with South Carolina State University, close to his hometown. But SCSU discontinued its baseball program literally days after his signing, spurring Wilson to attend Spartanburg Methodist College instead, playing there in 1974 and ’75. It was while with the Pioneers that Wilson was drafted by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the fourth round of the 1976 amateur draft. Surprisingly, he decided not to sign with LA, transferring instead to the University of South Carolina, where he played the outfield and pitched, hoping to showcase his versatility to other major-league teams. His first coach there was former Yankees star Bobby Richardson. In 1977, now under the tutelage of June Raines, who had taken over the program after Richardson resigned at the start of that season, the Gamecocks played in the College World Series. They lost to Arizona State University, 2-1, but Wilson was named to the All-Tournament team outfield.1

The success of that South Carolina squad, along with Wilson’s decision to turn down the earlier offer from the Dodgers, resulted in his being chosen again, this time in the second round of the 1977 draft by the New York Mets. He signed a contract and was assigned to Wausau, Wisconsin, a Mets affiliate in the Midwest League. Appearing in 68 games in the outfield for Wausau, Wilson hit .290 in 245 at-bats; his power numbers (6 home runs, 32 RBIs) were not overly impressive, but that is not what had attracted pro scouts to him in the first place. It was his speed and defense that would keep him moving through the Mets’ system and in that first half-season he stole 23 bases in 30 attempts. Promoted to Double-A Jackson, Mississippi, the next year, Wilson had 497 at-bats, hitting .292 with 15 triples and 38 steals.

It was during this season that Wilson’s brother Richard affected his life. Richard had fathered a boy, now 4 years old, whom he would not or could not support, and on the night of June 22, 1978, Wilson married the boy’s mother, Rosa Gilbert, at home plate at Jackson’s Smith-Wills Stadium. The ceremony, held before a crowd of 1,200, included an archway of bats held up by team members. The reception took place on the field after the game, with everyone in attendance invited. Fans and teammates then chipped in for a bridal suite at a local hotel. (The marriage made Wilson, oddly enough, both the uncle and stepfather of Preston Wilson, who went on to have a career in the majors, crowning it with a World Series championship with the Cardinals in 2006.)

Called up to Triple-A Tidewater for 1979 and ’80, the speedy outfielder (he had given up pitching by then) racked up a combined 99 stolen bases in 125 tries and scored 176 runs; along with his .295 average through August of 1980, the Mets had seen enough. It was time to bring Wilson up to the Big Apple. Wilson made his major-league debut on September 2, 1980, in Los Angeles against the Dodgers, the team that had originally drafted him four years earlier.

Batting leadoff, Wilson grounded out to short against Dodgers starter Dave Goltz, then did the same in the top of the third. He ended the game 0-for-4, but the night was not a total loss as he drove in second baseman Wally Backman with another groundball, this time off reliever Bobby Castillo, who had replaced Goltz during a Mets four-run rally in the top of the seventh. The Dodgers won, 7-5, and the Mets lost the next night as well, shut out 2-0 by LA’s Burt Hooton, with Wilson going 0-for-3, with a walk.

It was not until his third game, a daytime contest at San Diego on September 4, that Wilson collected his first hit, a single to left field off Padres starter John Curtis in his second at-bat. The Mets lost that contest too as Curtis threw a complete game in the 3-2 win. In fact, the Mets lost 13 straight games during this stretch, not winning again until they beat the Cubs at home on September 13. The franchise struggled through another poor campaign in 1980, their fourth consecutive losing season, and the team was obviously hoping for a spark from its promising farm system (as a matter of fact, the September 4 loss to the Padres also marked the debut of the Mets’ other projected star, third baseman Hubie Brooks). Wilson’s call-up was not a cause for immediate celebration however: In just over 100 at-bats the rest of the 1980 season, he hit only .248 with eight extra-base hits (none of them homers) and just 12 walks versus 19 strikeouts. He stole seven bases and made only two errors in 229 innings, underscoring what the Mets knew were his greatest talents — above-average fielding and dazzling speed.

The following season showed a slight uptick in Wilson’s offense as he batted .271 during the strike-shortened 1981 campaign. And though he drove in just 14 runs, he stole 24 bases and played all three outfield positions to the tune of a .983 fielding percentage. (Brooks on the other hand hit .307 in ’81 with 38 RBIs; however, he also made 21 errors in 93 games. These early numbers were already foreshadowing the future careers of the two youngsters: one the superior hitter, the other the speedy defensive star.)

Wilson’s next three seasons were eerily consistent as he hit .279 in 1982, then batted .276 in each of the next three years. He drove in between 51 and 55 runs each season and tied the team record with 9 triples in 1982, to go with 58 steals.2 Though consistent, Wilson’s offensive numbers were still not awe-inspiring. He led the league in at-bats in 1983, but struck out what would remain a career-high 103 times with only 18 unintentional walks. His on-base percentage in the modern SABRmetric world would probably have bought him a ticket back to Tidewater, averaging out to just .307 during this stretch. But his 10 home runs in 1984 would also be his career high, while his 10 triples that year set a new Mets record.

Despite his semi-anemic offensive numbers, Wilson became entrenched at the top of the Mets lineup as the team strengthened its personnel through the mid-1980s. The development of the franchise’s next burgeoning star, Darryl Strawberry, along with the acquisition of recent MVP Keith Hernandez from the Cardinals, helped swing the team from the embarrassment of 94 losses in 1983 to a second-place, 90-72 finish in ’84. The subsequent trade for All-Star Gary Carter from Montreal (in a deal that sent Hubie Brooks to the Expos) helped the Mets stay in the battle for the NL East crown late into 1985; they finally succumbed to the Cardinals, but enjoyed their best season since the Miracle Mets of 1969, racking up 98 wins and finishing three games behind St. Louis.

Unfortunately for Wilson, he missed much of the excitement. The center fielder had been experiencing discomfort in his right shoulder for more than a year and was finally forced to undergo surgery for torn cartilage on July 3, 1985. Surgeons reported the discovery of “fraying and tears of the labrum,” along with other cartilage damage. Wilson did not return to the Mets until September 1 and did not see regular action until a week later. He ended the season with fewer than 400 plate appearances, once again hitting .276, with 26 RBIs and 24 stolen bases.

The next season, 1986, was the campaign that Met fans had been awaiting for 17 years. Wilson’s year began as badly as the previous one had ended, however, as he was hit in the eye from 40 feet away by a ball thrown by shortstop Rafael Santana during a spring-training base running drill. The blow shattered the eyeglasses that Wilson had begun wearing the year before to cut down on outfield glare. He was carted off the field and took 21 stitches above the eye and four more on the side of his nose. “The glasses … took the full impact of the blow and probably prevented more damage,” remarked the doctor attending the injury.3 Wilson did not return to the lineup until May 9, but the team suddenly had some depth in the outfield with veterans George Foster and Danny Heep absorbing innings. When Wilson returned to the field, he found himself sharing center-field duties with young fireball Lenny Dykstra, who was playing his first full season. It was not until Foster was released in early August that Wilson was able to play regularly again, settling into left while Dykstra became the regular center fielder.

But the 1986 Mets could do no wrong: The team led the NL East practically wire-to-wire, winning 108 games. Their 13-3 record in April included a franchise-tying 11-game winning streak; they lost only 18 games between May and June, and by midsummer the division race was pretty much over. The team’s stars and their exploits of that season are remembered not only by Mets fans but by fans of all teams; from Carter’s 105 RBIs to Strawberry’s 27 home runs, to pitching phenom Dwight Gooden’s 17-6, 2.84 season. There was something special happening at Shea Stadium and at the top of the order every day sat the “Mookster.” He was the team’s sparkplug, still one of the most popular Mets among their fans, and his statistics were on the rise. His batting average jumped to .289, his on-base percentage to .345. He scored only 61 runs with just 25 stolen bases, but his 72 strikeouts were a new low for a full season. He also enjoyed his best season in the field, committing only five errors. But for this team the numbers were secondary as the Mets bulldozed their way through the National League, seemingly just waiting for their date with the postseason. It came in the form of the Houston Astros in the NLCS. Led by its ace, Mike Scott, Houston made the series uncomfortable for the Mets, dragging them through a nailbiting Game Six before the Mets finally prevailed in the 16th inning. Wilson dragged through the NLCS himself, collecting only three hits in 26 at-bats, striking out seven times and stealing just one base.

The Red Sox followed in the World Series and the two league champions fought through an all-time classic, the Mets battling back from a 2-0 hole to bring the Series back to Shea for Games Six and Seven. It all came to a crescendo on a cold Saturday night in October, with Wilson standing at the plate and 55,000 fans screaming in anticipation. Down 5-3 in the bottom of the 10th inning of Game Six, the first two batters flied out; then the gritty Mets bunched consecutive singles by Carter, rookie Kevin Mitchell, and third baseman Ray Knight to plate a run. Red Sox manager John McNamara called on veteran reliever Bob Stanley to replace Calvin Schiraldi and get the Series-clinching final out. Stanley had faced Wilson three times already in the Series and had retired him twice. After seven pitches, the count was 2-and-2, but on pitch number eight, the ball got away from catcher Rich Gedman, almost hitting Wilson, bouncing away and scoring Mitchell from third base. Two pitches later the most infamous groundball in World Series lore rolled down the first-base line and trickled into history. “I had a pitch I should’ve handled really well, middle in low, but kind of rolled over it,” said Wilson when asked about the fateful pitch. “I knew the ball was hit slowly, so I gotta run, and the pitcher was slow getting there. I didn’t see the ball go through (Bill) Buckner, I just saw it go behind him. …” Wilson maintained that he would have beaten the slow and injured Buckner to first, even had he made the play cleanly.4 The Mets won Game Seven two nights later to capture the second world championship in their history. Wilson’s numbers for the Series were a tad better than they had been for the NLCS: a .269 average, with a double and three stolen bases. He struck out six times.

As often happens with championship teams, the following year brings roster changes that ultimately affect team chemistry. In this case, the Mets decided they needed Kevin McReynolds, so they traded a package of young players (including one of ’86’s heroes, Kevin Mitchell) to the San Diego Padres. The acquisition did not sit well with Wilson or Dykstra, and Wilson even went so far as to request a trade, which was ignored; he and Dykstra ended up sharing time in center, with McReynolds playing left. It turned out to be one of Wilson’s finest offensive seasons as he hit a career-high .299 in just under 400 at-bats, with 19 doubles, 34 RBIs, and 21 stolen bases. And despite 92 wins, the Mets found themselves looking up at St. Louis again, finishing three games behind the eventual NL champions.5

Wilson and Dykstra continued their tag-team act in 1988, but Wilson appeared to be on the downturn. Through the first hundred-plus games of the season, he was hitting only .234 with 19 RBIs and 31 runs scored. The team, however, was playing well. Ray Knight and Rafael Santana had been replaced by Howard Johnson and Kevin Elster respectively, but most of the roster from ’86 was still intact and the Mets led the Pirates for most of the year. Beginning with a series in Pittsburgh on August 5, Wilson turned his season around, hitting.386 from that point on, driving in 22 runs and scoring 30 more.

On September 5 against the Pirates, he matched a career high with four RBIs, including a three-run homer in a 7-5 victory. The win gave the Mets a 10-game lead in the division and they cruised to their second postseason in three years. Wilson ended the ’88 campaign at .296 with 41 RBIs. His strikeout-to-walk ratio was a respectable 63-27. But things did not go as well in 1988 as they had two years before and the Mets were upset in the NLCS by the Dodgers, a team they had beaten 10 out of 11 during the regular season. Wilson’s performance did not help as he collected a measly two singles in 13 at-bats with two walks and a stolen base attempt that was unsuccessful.

The Mets showed their faith in Wilson when they picked up his option before the 1989 season. However, on June 18, he was the victim of another outfield glut as, with the Mets only two games behind the Cubs in the NL East, the team traded the popular Dykstra to Philadelphia for up-and-coming center fielder Juan Samuel. Understanding that the younger Samuel would get the bulk of playing time, Wilson once again requested a trade and this time the Mets accommodated him, sending him to the Toronto Blue Jays for reliever Jeff Musselman and minor-league pitcher Mike Brady at the July 31 trading deadline.6

Over all or parts of 10 seasons, Wilson ended his Mets career with a batting average of .276. He hit 60 home runs, drove in 342 runs, and scored 592 runs. He stole 281 bases, getting caught less than 100 times. His one outstanding blemish was an on-base percentage of just .318. During that decade, he could also lay claim to being one of the most popular Mets of all time.

But Wilson’s career was not over. After hitting just .205 for New York in 80 appearances over the team’s first 105 games (possibly another reason team management willingly accommodated his trade request), Wilson played in 54 games for Toronto, hitting .298. He also made his return to the postseason; the Blue Jays lost in the ALCS to Oakland.

Obviously, the Toronto organization liked what they saw and signed Wilson to a two-year contract in the offseason. A rejuvenated Wilson enjoyed a successful 1990. In 629 at-bats (the most he had since 1983), Wilson hit only .265 but drove in 51 runs (his most since ’84) and stole 23 bases, scoring 81 times. Playing mostly center field, he made only five errors and posted a.992 fielding percentage, fifth among AL outfielders.

Wilson’s playing time diminished greatly in 1991 when the Blue Jays acquired Devon White from the Angels. Playing in only 86 games, Wilson batted just .241. His OBP dipped below .300 and he scored just 26 runs. But the Jays made the playoffs once again, and Wilson snuck in eight more at-bats, collecting two singles and stealing a base. His last game in the major leagues was on October 13, 1991, when he started Game Five of the ALCS in left field against Minnesota, going 1-for-4 and scoring a run. The Jays lost 8-5, giving the Twins the AL pennant. The Blue Jays decided not to pick up Wilson’s contract for 1992 and after some interest was expressed, ironically enough by the Red Sox, he got no more phone calls. Mookie Wilson’s major-league career was over.7

Wilson went to college after he retired, receiving a bachelor’s degree from Mercy College in New York in 1996, and obtained a commercial driver’s license three years later. But his love was always baseball and he stayed involved.8 He was the Mets first-base coach from 1997 through 2002, managed their rookie-league team in Kingsport, Tennessee, for two seasons, then moved on to skipper the Class-A Brooklyn Cyclones in 2005. He also served as the organization’s baserunning coordinator, and returned to the major-league first-base coaching box in 2011.9 After that season he was moved into a front-office “ambassador” position, and it was here that Wilson had his first whiff of controversy during his 30-plus years in baseball. “It’s sad to say this, but I have basically become a hood ornament for the Mets, “Wilson wrote in his autobiography. “I would have liked an explanation as to why I was moved from first-base coach to the ambassadorship, but none was ever given. … I understand that jobs come and go in the baseball business, but sometimes management loses sight of how these moves play with people’s lives. … They just dictated my career as a player and a coach and it wasn’t right.”10 Nevertheless, Wilson did rejoin the Mets in 2012 in a job described as roving instructor and club ambassador.

As of 2015 Wilson was still married to Rosa and they have three children. They lived in Lakewood Township, New Jersey, and shortly after the 1986 World Series opened an educational center for girls called Mookie’s Roses near their home. He also appeared at shows and on the field with the player he has become most associated with — Bill Buckner. Wilson said a day did not go by that he wasn’t asked about the play, and that he approached it with mixed emotions. “Initially it did bother me that my career was defined by one play,” he said. “I think I’ve done more for the game than just hit a groundball — not even a hard-hit groundball. But I came to understand … it’s part of baseball history. It’s part of the Mets history, and to deny being a part of it is wrong.”11

There was not much wrong in William “Mookie” Wilson’s career, least of all that little roller.

Notes

1 imdb.com/name/nm1146525/bio. The All-Tourney second baseman was ASU’s Bob Horner, who went on to star at first base with the Atlanta Braves.

2 Mookie Wilson profile, ultimatemets.com/profile.php?PlayerCode=0300.

3 Joseph Durso, “Right Eye Injured,” New York Times, March 6, 1986.

4 David Itzkoff, “Mookie Wilson on Life After the Mets,” New York Times, April 25, 2014.

5 “Question of the Week: Should Wilson and Dykstra Platoon?” New York Times, May 7, 1989; Craig Wolff, “Wilson Adapts to Platoon Job,” New York Times, June 13, 1986.

6 Joseph Durso, “Wilson Sent to Jays in Musselman Deal,” New York Times, August 2, 1989. Upon leaving the Mets, Wilson held the team record for stolen bases (281) and triples (62), but both records were surpassed by Jose Reyes.

7 “Blue Jays Drop Wilson,” New York Times, October 29, 1991.

8 Ira Berkow, “Graduation Day for Wilson: Pomp and Studious Stance,” New York Times, May 29, 1996.

9 Andrew Keh, “Mets Announce Coaching Changes,” New York Times, October 5, 2011; George Willis, “Wilson to Take the Field as Mets’ First Base Coach,” New York Times, October 18, 1996.

10 Mike Puma, “Mookie Wilson: I Went From Mets Hero to ‘Hood Ornament’, ” New York Post, April 25, 2014; Mookie Wilson with Eric Sherman, Mookie: Life, Baseball and the ’86 Mets (New York: Berkeley Books, 2014).

11 Bill Price, “Mookie Wilson has come to understand his place in Mets history ahead of series with Red Sox,” New York Daily News of Thursday, August 27, 2015.

Full Name

William Hayward Wilson

Born

February 9, 1956 at Bamberg, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.