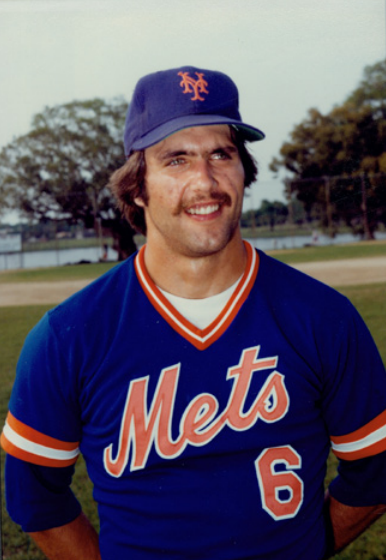

Wally Backman

Wally Backman was perhaps the first major-league manager fired before his team played a game. His fiery personality may have cost him another chance at managing in the majors. Three times he spent short stints in jail. He declared bankruptcy. From this sordid interval in life, he emerged to become a successful minor-league manager.

Wally Backman was perhaps the first major-league manager fired before his team played a game. His fiery personality may have cost him another chance at managing in the majors. Three times he spent short stints in jail. He declared bankruptcy. From this sordid interval in life, he emerged to become a successful minor-league manager.

Walter Wayne Backman was born on September 22, 1959, in Hillsboro, Oregon, to Sam and Ida Backman. Sam was a railroad switchman who had spent a few years in the Pittsburgh Pirates system. Wally was the third of six children.1 Sam taught his son the game, while both parents instilled the desire to win. “I was raised to win. I credit my parents for that,” Backman said.2

Backman was drafted 16th overall in the 1977 June amateur draft out of Aloha (Oregon) High School. He was assigned to the Little Falls Mets of the New York-Penn League. There, Backman played in all but two of Little Falls’ games in 1977, mostly at shortstop. The 17-year-old led the team in most offensive categories, including at-bats (255), runs (44), hits (83), stolen bases (20), and batting average (.325)

Backman continued his ascention in 1978, playing for the Lynchburg Mets of the Class-A Carolina League, where he helped lead the team to the league championship. He played the entire season at shortstop, and again showed off his offensive skills. Backman led the team in at-bats (494) and runs (86), and was second on the team with a .302 batting average. His speed was on display as well; he led the team in stolen bases (42) and triples (9), but his 99 strikeouts were the third most in the league. Bakcman’s fielding, however, was of concern. He had a .947 fielding average at shortstop and led the team with 30 errors. Despite the shaky fielding, the Mets promoted Backman to Jackson of the Double-A Texas League, most likely due to his offense and ability to get on base at a nearly .400 clip.

Backman’s 1979 season was his first facing some challenges. His offensive numbers dipped, but he was still second on the team in runs (63) and led the team with five triples. Once again, his defensive skills were subpar: 30 errors with a .933 fielding percentage.

The Mets still liked what they saw offensively from Backman, enough to promote him to Triple-A Tidewater for 1980. The organization had a plan. Backman was switched to second base. In his limited action at shortstop that season, his fielding percentage was .931 but in games at second, it jumped to .965. His skills on offense became sharper. He was among the team leaders for most offensive categories. When the Mets made their September call-ups, Backman was on the list, and was immediately thrown into the fire. Mets second baseman Doug Flynn had fractured his right wrist on August 20, paving the way for Backman to play.3 Backman played in 27 of the Mets’ remaining 32 games, primarily at second. His fielding was stellar — only one error — and he batted .323 with a .396 on-base percentage, better than any of the Mets regular starters.

Backman’s 1980 call-up and 1981 spring training earned him a spot on the 1981 Mets as a reserve infielder.4 He played in 26 games, mostly as a pinch-hitter, before the Mets sent him back to Tidewater on June 8, just days before the players elected to strike. Backman was upset by the demotion and the lack of steady playing time.5 He played in only 21 games for Tidewater before tearing his rotator cuff. Backman missed the rest of the 1981 season while rehabbing the injury.

After the 1981 season the Mets decided to retool their middle infield. They traded their starting shortstop, Frank Taveras, and their starting second baseman, Doug Flynn, with the idea of giving Backman a chance to take over second base, and Ron Gardenhire to take over at shortstop.6 New manager George Bamberger worked out the infielders at all positions during spring training in an effort to create a well-rounded infield.7 Backman batted.272 and his on-base percentage (.387, best among starters on team) was again his calling card, but he gained a reputation for bad defense, which he attributed to his rotator cuff injury. “I got labeled that year for a bad glove and it really bothered me,” he said a couple of years later. “The season before I tore my rotator cuff, and in 1982 it still bothered me.”8 Like 1981, Backman’s 1982 season ended early when he fell off a bicycle and broke his collarbone.9

Backman was on the trading block during the offseason but again found himself in the mix for a starting role on the 1983 Mets.10 He impressed the coaches with his offense during the spring. Bobby Valentine, the Mets’ infield coach, called Backman the best hitter11 but fans and writers still regarded him as a poor defender.12 He made the team, but played sparingly until he was sent down to Tidewater on May 17. The demotion upset Backman, and he requested a trade. “I’ll go and play hard, but at the end of the season I hope the Mets trade me or release me,” he said. “I really need to get away from this organization. There is no place in it for me.”13 Tidewater (and future Mets) manager Davey Johnson helped Backman get back on track. Backman praised Johnson. “The best thing that happened to me was having Dave Johnson as a manager last year,” he said in 1984. “Dave put me leadoff to begin the season. He saw what I could do and had confidence in me. That took a lot of the pressure off. I could relax and play my game.”14 Backman’s typical good offense became better, with a .316 batting average, but it was his defense that was the story. He made only 10 errors at second. Backman credited former second baseman Johnson with this turnaround too, saying, “In the field he showed me how to anticipate situations, and showed me what I’d been doing wrong on the double play.”15 Johnson’s work paid off, as Backman was the favorite for a Mets starting position entering 1984 spring training. Johnson had also been named the Mets manager.16

In 1984 Backman started 108 games at second for the Mets, batted .280 and made only 10 errors at second base. For the first four months of the season, Backman platooned with Kelvin Chapman. When Chapman was sent down to the minors, Backman was given the job full-time job and he performed well offensively and defensively.17 The 98-win Mets finished in second, three games behind pennant winner St. Louis in the NL East.

Still, Backman’s splits against left-handers and right-handers (.122 and .324 respectively) were cause for concern, so before the 1986 season the Mets traded for Minnesota second baseman Tim Teufel.18 Backman initially took the trade in stride, saying, “They’re looking for anything to strengthen the team.”19 Meanwhile, he lost his arbitration case against the Mets. He asked for a salary of $425,000 but was awarded $325,000.20

Spring training did nothing to clear up the competition at second. Backman entered the season platooning with Teufel, playing against right-handed pitchers.21 He rose to the challenge, batting .320 as the Mets took first place on April 23 and never gave up the position. Backman played in 12 of the 13 Mets postseason games, batting .238 in the NLCS against Houston, and.333 in the World Series.

Before the 1987 season Backman signed a three-year, $2 million contract to continue to platoon at second for the Mets.22 Backman was outspoken about his teammates and their willingness to play hard. He and teammate Lee Mazzilli accused star outfielder Darryl Strawberry of faking an injury for two games. Strawberry responded, “I ought to bust that little redneck (Backman).”23

Backman had two solid seasons platooning for the Mets. However, the team wanted to give one of its top prospects, Gregg Jefferies, a chance at second so Backman was put on the trading block again, and in December 1988 he was traded to the Minnesota Twins for three minor-league pitchers.

After a 100-win 1988 season, the Mets were expected to compete for the league lead, but a slow start to 1989 had people questioning many of the offseason moves, including the trade of Backman. One columnist called the trade of “feisty Wally Backman … a move more questionable with every lethargic game the Mets play.”24 But Backman was having his worst year ever in Minnesota, hitting .231 for the fifth-place Twins, and was released after the season. (The Mets finished in second place in the NL East and Jefferies was third in Rookie of the Year voting.)

Backman bounced around once he left the Twins. He spent 1990 with Pittsburgh, and 1991 and 1992 with Philadelphia, and was released by both teams. Before the 1993 season, he signed a minor-league deal with Atlanta, but was cut before the season began.25 He caught on with Seattle for 10 games, but was released on May 17. Backman retired to Oregon to live with his wife, Sandi, and his four children, but found himself wanting to get into managing.26

Backman spent his first three managerial years with independent teams. In 1997 he managed the Catskill (New York) Cougars of the Northeast League, but could muster only a 3-23 record. In 1998 Backman managed the Bend (Oregon) Bandits of the Western Baseball League. Just before spring training, he was bitten on the forehead by a poisonous spider. While recovering, he was hit by a foul tip while standing next to the batting cage, causing more swelling. Despite his travails, his team finished the season in second place at 43-46. He then spent two years with a Bend rival, the Tri-City (Washington) Posse. Backman finished that stint with an overall 88-92 record.27 The Chicago White Sox hired him to manage their Winston-Salem team in the Carolina League. He then spent two successful years with Double-A Birmingham, going 152-125 with the Barons. Backman’s outspoken personality got him fired, though, for openly campaigning for the job of White Sox manager Jerry Manuel.28

After the 2004 season the Mets fired manager Art Howe. Backman was mentioned as a potential replacement after he led the Lancaster JetHawks of the California League, an Arizona Diamondbacks farm team, to an 86-54 record and being named the Minor League Manager of the Year by The Sporting News. (His fiery personality continued to shine through; he was ejected six times and suspended for bumping an umpire.)29 Backman withdrew his name from Mets consideration when the Diamondbacks decided to interview him for their managerial opening.30

Backman was hired as the Diamondbacks’ manager on November 1, 2004, but was fired four days later after the New York Times ran a story about legal issues in his past that he had not disclosed to the Diamondbacks during his interview. His first wife, Maggie, had filed for a restraining order against him. (A judge later vacated the order.31) Backman had also been convicted of drunk driving in January 2001. He was sentenced to a year in jail, but served only one day, and the remainder of the sentence was suspended unless Backman committed another crime within five years. On October 7, 2001, Backman was charged with five misdemeanors stemming from an incident involving his second wife, Sandi. He again served one day in jail, and was placed on an alcohol-free one year probationary period. (Sandi later said the incident was overblown and “[t]he idea of Wally hitting me is comical.”32) In February 2003 Backman filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. The Diamondbacks said they were unaware of any of the issues surrounding Backman.33 Backman later served 10 days in jail for violating the conditions of the 2001 suspended sentence.34

Backman remained out of baseball until 2007, when he took over the South Georgia Peanuts of the South Coast League. “[If] this is what I need to get another shot in Organized Baseball, I’ll do it,” he said.35 He shared his $40,000 salary with three of his coaches.36 While with the Peanuts, Backman unleashed a memorable on-field tantrum. One of his players was ejected for arguing balls and strikes. Backman emerged from the dugout to protect his player, and was thrown out of the game. He then littered the field with 22 bats and a bucket of baseballs.37 The incident was caught on tape for a TV show documenting the South Coast League, Playing for Peanuts. Even with this incident, Backman’s tenure with the Peanuts was successful. His team won the league championship and five Peanuts were signed to major-league contracts.38

Backman stayed in the independent leagues for 2008, managing the Joliet JackHammers of the Northern League. He lasted through mid-2009, when a 24-42 record got him fired. Backman acknowledged his failure to lead the team, saying, “The fans in Joliet deserve a winner. I’m disappointed that we could not get the job done.”39

Before the 2010 season, the Mets brought Backman back into the fold to manage the Brooklyn Cyclones of the New York-Penn League. He had not been affiliated with Organized Baseball since the Arizona firing, and quickly addressed that issue. “I take full responsibility for the things that I did wrong,” Backman said at his introductory press conference. “But I want to move forward again and to start here, I think, is a good start for me.”40 The Mets inserted a zero-tolerance clause in his contract.41

Backman responded by guiding the team to a league-best 51-24 record. Brooklyn lost in the playoff finals to Tri-City, but Backman made an impact on the Mets organization. When Jerry Manuel was fired as the Mets’ manager after a fourth-place finish, Backman was interviewed and considered a finalist, but lost out to Terry Collins.42 Instead, Backman was promoted to Binghamton (Double-A Eastern League) for the 2011 season. For 2012 he was promoted to manage Triple-A Buffalo. The team finished 67-76, and Backman was his typical outspoken self. He described one of his pitchers as a “4-A guy” and opined “[f]or the major leagues, he has no real swing-and-miss pitch.”43

In 2013 the Mets switched their Triple-A affiliation to the Las Vegas 51s of the Pacific Coast League. Backman led the team (81-63) to a first-place finish, but lost in the playoffs to Salt Lake. In 2014 they finished first again with the same 81-63 record. Despite losing in the playoff semifinals again (this time to Reno), Backman was named PCL Manager of the Year. In 2015 the 51s missed the playoffs.

Backman also had a hand in the Mets’ success in 2015. Three pitchers who played important roles in the team’s march to the World Series, Matt Harvey, Steven Matz, and Noah Syndergaard, as well as infielder Wilmer Flores, all played for Backman in the minors. Through the 2015 season, Backman had a 422-369 record while managing in the Mets organization.

Notes

1 Jeff Pearlman, “Three Years Later, Backman Still Trying to Get to the Bigs,” ESPN, sports.espn.go.com/espn/page2/story?page=pearlman/071022 (accessed December 1, 2015).

2 Ibid.

3 Joseph Durso,”Mets Lose 7th in Row; Flynn Idled 2-6 Weeks,” New York Times, August 21, 1980.

4 Joseph Durso, “Leary Earns a Place on Mets Roster and Will Face Cubs Sunday,” New York Times, April 6, 1981.

5 Thomas Rogers, “Baseball Notebook: Mets’ Backman Expands Strike,” New York Times, June 16, 1981.

6 Murray Chass, “Mets Trade Flynn; Expos Get Taveras,” New York Times, December 12, 1981.

7 Jane Gross, “Met Plan: Versatile Infield,” New York Times, February 24, 1982.

8 William C. Rhoden, “Backman Fills Gap for Mets,” New York Times, July 12, 1984.

9 Ibid.

10 Joseph Durso, “Stearns on Disabled List, Seaver Ailing,” New York Times, March 28, 1983.

11 Gerald Eskenazi, “Mets Try 5 Players in Double-Play Role,” New York Times, March 21, 1983.

12 Joseph Durso, “Second Base Is Puzzling Mets,” New York Times, March 3, 1983

13 Joseph Durso, “Strawberry’s 3-Run Homer Paces Mets,” New York Times, May 18, 1983

14 Rhoden.

15 Ibid.

16 Lawrie Mifflin, “Backman Stays In Mets’ Plans,” New York Times, December 21, 1983.

17 “Backman Responds to Full-Time Duty,” Chicago Tribune, August 1, 1985.

18 Joseph Durso, “Backman Facing Challenge At Second Base,” New York Times, February 25, 1986.

19 Ibid.

20 Murray Chass, “Backman Loses Case to Mets,” New York Times, February 20, 1986.

21 Michael Martinez, “Backman is Facing Another Battle,” New York Times, March 30, 1986.

22 Murray Chass, “Mets Give Backman a $2 Million Pact,” New York Times, January 22, 1987.

23 Johnette Howard, “Strawberry’s Latest Strikeout May Be Last,” Washington Post, April 14, 1994.

24 George Vecsey, “Baseball, Everybody, Baseball,” New York Times, June 2, 1989.

25 “Braves Jettison Backman for Cabrera,” New York Times, April 2, 1993.

26 Filip Bondy, “Arachnophobia: Spider Bite Adds to Backman’s Web of Miserable Luck,” New York Daily News, May 24, 1998.

27 Ibid.

28 Jack Curry, “Backman Named Arizona’s Manager,” New York Times, November 2, 2004.

29 Lee Jenkins, “As Mets Look Ahead, They Look Back,” New York Times, September 23, 2004.

30 David Waldstein, “Mets Will Hire Backman to Manage In Brooklyn,” New York Times, November 14, 2009.

31 Pearlman.

32 Ibid.

33 Jack Curry, “The Past Costs Backman His Job, Four Days After He Received It,” New York Times, November 6, 2004.

34 “Sports Briefing,” New York Times, December 4, 2004.

35 Pearlman.

36 Jack Curry, “Backman Ready for His Show of Shows,” New York Times, June 17, 2007.

37 Pearlman.

38 Ibid.

39 oursportscentral.com/services/releases/?id=3875509.

40 Ben Shpigel, “After 5 Years, Backman Gets a Second Chance,” New York Times, November 18, 2009.

41 Ibid.

42 David Waldstein, “Mets Choose the Intense Collins as Their Manager,” New York Times, November 22, 2010.

43 Hunter Atkins, “A Long Road Home, With Further Still to Go,” New York Times, June 17, 2012.

Full Name

Walter Wayne Backman

Born

September 22, 1959 at Hillsboro, OR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.