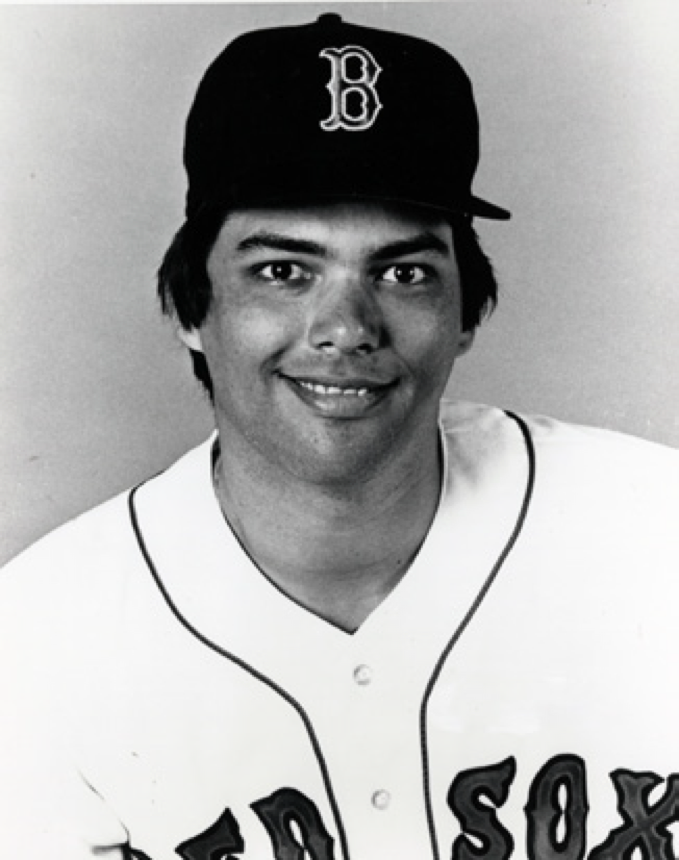

Calvin Schiraldi

If Calvin Schiraldi had never been called upon to pitch in the sixth game of the 1986 World Series, we might think of his career in baseball as a story of encountering and overcoming adversity — a series of comebacks. But Red Sox manager John McNamara did call Schiraldi in from the bullpen in the bottom of the eighth. And his name became synonymous with crumbling under pressure.

A hard-throwing right-handed pitcher since high school, Schiraldi spent eight years in the majors with six different teams between 1984 and 1991. He never again reached the level of performance he had in 1986, when he emerged from Triple-A Pawtucket to become the Red Sox’ closer. His combined won-lost record for the two teams was 8-5 as he earned 21 saves and 114 strikeouts in 95 innings with a 2.08 ERA.

Calvin Drew Schiraldi was born on June 16, 1962, in Houston, Texas, and grew up playing baseball in and around Austin — establishing himself early as a strong pitcher. “He always threw hard,” his father, Joe, told a reporter when recounting the story of Calvin’s path from the backyard to the big league.1 Joe had been a talented college athlete himself — attending Texas A&M in the early 1950s on a basketball and track scholarship before the army and working in the office products business for Remington Rand and G&LVBJ Co. Calvin’s mother, Ramona (Powell), attended Baylor University and was a secretary and a teacher aide while raising Calvin and his sister, Rhonda. Both parents watched as Calvin helped pitch his Babe Ruth team into the state championship. Starting in his junior year at Austin’s Westlake High School, Schiraldi was being watched and followed by major-league scouts.

In June of his senior year, the 6-foot-4 Schiraldi was drafted by the Chicago White Sox in the 17th round of the 1980 amateur draft. Two days later, he pitched the game that earned Westlake the AAA state championship, defeating the defending champion DeSoto in a three-hour game. Schiraldi ended the game with a gutsy called strike on a 0-and-2 count to win 11-10. He was named to the All-State AAA team and chose to attend the University of Texas instead of signing with the White Sox.

At Texas Schiraldi joined future Red Sox teammates Roger Clemens and Spike Owen as the Longhorns won the 1981 Southwest Conference title and made it to the College World Series, only to be eliminated by top-ranked Arizona State. Schiraldi pitched in several games that freshman year, as did Clemens, but neither pitched during the College World Series.

The following season, Schiraldi saw much more action, amassing a 13-2 record with a 3.23 ERA as the Longhorns returned to Omaha for the 1982 CWS. This time the team’s 57 wins and 4 losses earned its place as the top-ranked entrant. Schiraldi took the mound in the semifinal against Wichita State on June 11, 1982. After gaining a 2-1 lead in the first inning, the Longhorns looked as though they might repeat the two wins they’d had over Wichita State during the regular season. But in the top of the second inning, Schiraldi accidentally hit Wichita State outfielder Kevin Penner just below the left eye with a 90-mph fastball, fracturing four bones and knocking him unconscious. Some accounts of the game noted that Penner lay in the batter’s box for 10 minutes while awaiting an ambulance.

After Penner was taken to St. Joseph’s Hospital, where he was reportedly in a coma for two days, Wichita scored six runs in the next inning as Schiraldi alternated between walking batters and giving up hits. Wichita eventually eliminated Texas in an 8-4 victory that Longhorns coach Cliff Gustafson attributed in large measure to Penner’s injury.

“It’s very difficult for you to see something like that happen — be afraid a guy is seriously injured, and go on the mound and concentrate like you need to. I think it was a big factor,” Gustafson told reporters.2

In later interviews Schiraldi revealed how much it had rattled him. He told Michael Kelly of the Omaha World Herald, “It bothered me the whole rest of the summer. Just thinking that you might have injured a player like that…I was terrible over the summer: 4-6 with a 7.00 ERA. I didn’t feel like I wanted to throw any more. Mentally, it affected me.”3 The following year, there was much talk about whether Schiraldi would rebound and whether Penner would ever play again. The tone was nearly identical to discussions after the 1986 World Series.

But in 1983 both men overcame the setback in dramatic fashion. After multiple surgeries and a long recovery, and with the aid of a special face mask on his batting helmet, Penner led Wichita State in hitting with a .437 average. He was named to the US Pan-American Games baseball team. Schiraldi came back stronger than ever, with a 12-2 record, 1.86 ERA, and 101 strikeouts going into the 1983 CWS. Schiraldi stopped James Madison 12-0 on five hits in the tournament opener, then led the team to a 10-inning victory over Alabama, striking out 11 Alabama batters in 5⅓ innings of relief. Clemens won the final game, but Schiraldi’s 2-0, 0.63 ERA performance earned him a place on the All-Tournament Team and the series’ Most Outstanding Player title. More than 30 years later, with years in the major and minor leagues behind him, Schiraldi still pointed to the 1983 College World Series victory as his favorite moment as a player.

A few days after the victory, the New York Mets’ director of player personnel, Lou Gorman, signed Schiraldi, whom he’d picked in the first round of the free-agent draft earlier that month. Gorman, for whom Schiraldi would later play in Boston, left for the Mets at the start of the season and Schiraldi was assigned to the Mets’ Lynchburg team in the Carolina League, where he had six starts before being promoted to the Double-A Texas League team in Jackson, Mississippi, where he went 3-3 in seven games, with a 5.82 ERA.

In 1984, his first full professional year, Schiraldi was once again an all-star pitcher. Again with Jackson, he went 14-3 and was voted the league’s most valuable pitcher. Promoted to the Tidewater Tides of the Triple-A International League, he went 3-1 before being called up to the Mets in late August.

On September 1, 1984, Schiraldi made his major-league debut as the starting pitcher in the second game of a Saturday doubleheader against the San Diego Padres. He lasted just 10 outs, allowing eight hits and five runs. He pitched 14 more innings in four games that month, earning two losses and a 5.71 ERA.

After 1985 spring training, the Mets sent Schiraldi to Tidewater, only to call him back two weeks later to start against the Cardinals in St. Louis. He pitched a six-hitter through six innings until being relieved by Roger McDowell and earned his first major-league victory. Then he pitched 7⅔ innings in three games before an infield hit by the Atlanta Braves’ Claudell Washington broke his toe. Schiraldi went on the disabled list, came back in June and pitched in five games, including a hammering at the hands of the Philadelphia Phillies in which he Schiraldi gave up 10 hits and 10 runs in an inning and a third. He was sent back to Tidewater and recalled again in September. He pitched part of an inning against the Expos to finish the year 2-1 with an 8.89 ERA in 10 games (four starts) with the Mets. He posted a 4-5 record, 3.50 ERA in 17 starts with Tidewater.

“I didn’t throw the ball that badly or pitch as poorly as it looked,” Schiraldi later told Peter Gammons of the Boston Globe. “It was a combination of a lot of things, some of it bad luck; that can happen in four starts. Then when I started to throw the ball well, I got sent down, got down on myself and had what I consider a poor year.”4

While on his honeymoon in Bermuda with his wife, Debra, in November, Schiraldi heard of his trade to Boston. Schiraldi, relief pitcher Wes Gardner, and outfielders John Christensen and La Schelle Tarver were traded for Boston’s veteran pitcher Bobby Ojeda and three minor-league prospects. Everyone had high hopes for Schiraldi, including Roger Clemens, manager John McNamara, and general manager Lou Gorman. Alan Simpson, editor of Baseball America, saw the possibility that Schiraldi could become a dominant pitcher in the American League. Comparing him to Clemens, Simpson said, “When both came out of University of Texas, I thought Calvin was the better prospect.”5

But at the end of 1986 spring training, there was talk of a lack of confidence. Maybe a change of scenery wasn’t doing him any good. He had a 14.54 ERA. He was switched to relief. His father told a reporter later that Calvin had called him upset about the change. His arm was sore. In mid-March, in a particularly bad outing against the Mets in St. Petersburg, he’d allowed six hits and six runs in two innings of relief. And yet he’d struck out three batters. Manager McNamara said. “Schiraldi had good stuff, threw hard, but did not make good pitches and that’s the second time that’s happened.”6

Schiraldi was sent to the team’s International League outpost in Pawtucket. He soon settled into the relief role and earned 12 saves in 31 games with a 2.86 ERA. “Mainly, I was trying to get people out any way I could,” Schiraldi told a reporter. “It just so happens my fastball came around, and that’s what was doing it.”7

When middle reliever Sammy Stewart went on the Red Sox injured list in late July, the team brought Schiraldi up. In his first outing, on July 20 in Seattle, he worked 2⅓ innings, giving up one run on three hits, with a walk and three strikeouts. Then on August 3, Schiraldi was sent out to face the Royals in a two-on, none-out jam in the ninth with the Red Sox leading, 5-3. Schiraldi ended in the game in 13 pitches — striking out Frank White and Steve Balboni and getting Mike Kingery to ground out on one pitch. It was his first save and, as the next eight weeks unfolded, the name “savior” was thrown around. In the next two months, Schiraldi earned a win or a save in 12 of 13 save opportunities. He finished the season with a 1.41 ERA and 55 strikeouts in 51 innings.

“He certainly came in here like someone who knew what he had to do,” Red Sox catcher Rich Gedman told Dan Shaughnessy of the Boston Globe. “But the key to getting any type of confidence up here is to have some kind of success. By now, any questions or doubts Calvin may have had have obviously been relinquished.”8

Schiraldi’s oscillations between setback and recovery shifted closer together when Boston entered the playoffs. Game Three on October 10 found the Angels and Red Sox tied with a victory each in the American League Championship Series. Oil Can Boyd had started the game and in the bottom of the eighth, when Schiraldi was called in to make his first postseason appearance, the Angels led 4-3. A walk, an error by Wade Boggs, and Ruppert Jones’s sacrifice fly helped Reggie Jackson add another run and the Red Sox lost the game, 5-3.

The next day McNamara put in Schiraldi to relieve Clemens in the bottom of the ninth after a leadoff homer by Doug DeCinces and a pair of one-out singles by Dick Schofield and Bob Boone. The Red Sox led, 3-1. Gary Pettis hit a double into left field, sending Schofield home. He then walked Jones, struck out Bobby Grich, and hit Brian Downing with a 1-and-2 curveball to force in the tying run. The game went into extra innings and Schiraldi lost the game in the 11th on two singles, an intentional walk, and a sacrifice bunt. Schiraldi cried in the dugout, shielded by a towel and his teammates.

Schiraldi was called upon again in the bottom of the 11th inning of Game Five. He was pitching for the third straight day, something he hadn’t done during the regular season, and facing the top of the Angels’ batting order. He struck out Rob Wilfong and Dick Schofield, then Downing went out on a foul caught by first baseman Dave Stapleton. The Red Sox won 7-6 and Schiraldi got the save. The Boston Globe’s Shaughnessy wrote the next day: “Imagine. Eighteen hours after he’d been enshrined in the Jim Burton/Bucky Dent Red Sox Hall of Shame, Schiraldi was in the middle of a postgame celebration. They never had time to get Schiraldi’s hat size. The goat horns didn’t fit.”9

Schiraldi avoided the metaphorical haberdashers again as he made his next playoff appearance. In Game One of the World Series, he replaced Bruce Hurst in the bottom of the ninth. After a walk to Darryl Strawberry, a groundout, and a flyout, Schiraldi sealed the 1-0 victory (and earned a save) by striking out pinch-hitter Danny Heep. “Right now it feels great,” he told reporters. “I don’t know what would have happened if we hadn’t won the AL championship. I would have kinda felt it was my fault if we hadn’t. Now we’re in the Series and I’ve got a job to do — I just want to do the job.”10

Schiraldi wasn’t called on again to do his job until the now infamous Game Six at Shea Stadium on October 25. He entered in the bottom of the eighth after Roger Clemens was pulled for pinch-hitter Mike Greenwell. The Red Sox were leading 3-2. A single, two bunts, and an intentional walk later, Gary Carter’s sacrifice fly sent Lee Mazzilli home. Darryl Strawberry flied out to end the inning, but the score was now tied, 3-3. Schiraldi held the Mets in the ninth and in the top of the 10th the Sox got two runs. In the bottom of the 10th Schiraldi took the mound. Leadoff hitter Wally Backman flied out to left, and Keith Hernandez flied out to center. Schiraldi was one out away from what would have been the first World Series title for the Red Sox since 1918. Then he allowed three straight singles to Carter, Kevin Mitchell, and Ray Knight. He was replaced by Bob Stanley, who threw a wild pitch, which allowed Mitchell to score the tying run. Mookie Wilson followed by hitting a groundball that rolled between the legs of Bill Buckner, scoring Knight and giving the Mets the win and forcing a seventh game.

Game Six has been the subject of so much attention and consternation, it is almost easy to forget that the Red Sox also lost the next game. And Schiraldi had a hand in that, too. After a rainout on Sunday, the teams met at Shea Stadium on Monday, October 27. Bruce Hurst, who was 2-0 in the Series, was the starter. In the bottom of the seventh inning, with the game tied, 3-3, Schiraldi took to the mound and again faced Knight, one of the heroes of Game Six. Knight hit a home run on a 2-and-1 pitch. Schiraldi then allowed Lenny Dykstra a single and threw a wild pitch to Rafael Santana before Santana singled and Dykstra scored. Mets pitcher McDowell bunted Santana to second and Schiraldi was pulled from the game. The Sox went on to lose 8-5 and Schiraldi was again charged with the loss.

Schiraldi was understandably crestfallen. “I feel responsible for what happened,” he told reporters. “I am responsible for what happened. I ought to feel like this.”11

Schiraldi returned as the short reliever on the 1987 roster. At spring training in Winter Haven, Florida, he told reporters the same thing he has been saying for three decades since. “I was probably more relaxed in the seventh game than in any other game. I didn’t feel nervous. I was ready to pitch. Things just didn’t work out.”12 He was, more or less, getting on with his life. The press had a harder time letting go than Schiraldi seemed to.

After an injury in May Schiraldi had an inconsistent season as he tried to bring some variety to accompany his still-strong fastball. His performance was 8-5 with six saves and a 4.41 earned-run average. He gave up 15 home runs in 83⅔ innings. In December 1987 he was traded to the Chicago Cubs along with starter Al Nipper for Cubs closer Lee Smith. At the time (and later) Schiraldi said he was a little surprised at the change, but happy to have an opportunity to be a starter again.

Cubs manager Don Zimmer knew the transition back to starter would be tough for Schiraldi, but he and pitching coach Dick Pole gave him time in 1988 to develop additional pitches, including a forkball he had picked up in a brief stint in the Instructional League at the end of the season. Schiraldi had a 9-13 record with a 4.38 earned-run average and finished only two of 27 starts. But during spring training in 1989, both the Cubs and Schiraldi expected improvement as he returned to the bullpen as a short reliever.

By mid-June the Cubs were in first place in the NL East, but Schiraldi’s performance was plagued by tendinitis in the shoulder and a sore elbow, for which he received cortisone shots. Zimmer seemed to be growing impatient — after a 10-7 loss to St Louis in mid-June he told reporters, “All I wanted was six outs from Calvin Schiraldi, but I didn’t get ’em.”13 It was tendinitis again — this time his triceps — and Schiraldi was forced to sit out several games.

In July Donnie Moore, the Angels reliever who couldn’t get the final out in Game Five of the 1986 ALCS, shot and seriously wounded his wife, then committed suicide in front of his children. At the time, pundits — and even other players — attributed Moore’s actions to never having gotten over that failure in the ALCS. There was ample evidence of Moore’s long-standing history of alcohol abuse and domestic violence predating 1986. But a myth was born. It had to have been frustrating to Schiraldi to have his name raised in news accounts of Moore’s death, not just because he got the save in that game, but because of the growing belief that Schiraldi was doomed to struggle with his own loss to “get over.” Some journalists almost seemed to be insinuating that perhaps he too should be on a watch list.

At the end of August, Schiraldi was 3-6 with four saves and a 3.78 ERA in 54 relief appearances. The Cubs were headed toward the playoffs, but minutes before the postseason deadline, the Cubs traded Schiraldi to the Padres along with outfielder Darrin Jackson and a minor-league player to be named later for outfielder Marvell Wynne and Luis Salazar. (The Cubs finished first in the NL East, and lost to San Francisco in the NLCS.)

Schiraldi’s arm continued to give him trouble in San Diego — a strained forearm forced him to leave a late-September game against the San Francisco Giants. But a few days later, on September 23, Schiraldi hit a three-run homer off Fernando Valenzuela of the Los Angeles Dodgers. It was Schiraldi’s first major-league home run (one of two in his career). Schiraldi made four starts with the Padres in 1989, going 3-1 with a 2.53 ERA.

In February 1990 Schiraldi signed a one year, $600,000 deal with Padres — the most he’d made in a season. That same month Lou Gorman was asked if he’d trade Lee Smith for Schiraldi and he paused and said he’d have to “consider it.”14

Schiraldi was the steady middle reliever until Andy Benes went out with a sore should in late July. Starting the second game of a doubleheader against the Cincinnati Reds on July 25, he gave up two runs on five hits in six innings. But out of the bullpen, by August 6 he had let his last 16 inherited runners score. A rumor again circulated that the Sox were interested in getting Schiraldi back in Boston, but Gorman put it to rest, telling reporters, “We have absolutely no interest in Schiraldi.”15

Schiraldi ended the year with a 3-8 record, one save, and a 4.41 ERA. In January 1991 he signed again for one year with the Padres. The new general manager was Schiraldi’s old booster Joe McIlvaine, the Mets’ former assistant GM. McIlvaine had been the scouting director in 1983 and had persuaded Gorman to sign him. Former Red Sox teammate Marty Barrett was also new to the team, having been released by Boston during the offseason. The reunion would be short-lived. Schiraldi blew a 6-1 lead in preseason play against San Francisco, and McIlvaine told reporters, “A major-league pitcher just doesn’t blow five-run leads.”16

The team waived Schiraldi before the season began. He would have been paid $740,000, but instead got $185,000 for not playing. He signed with the Houston Astros and was sent to their Triple-A team, the Tucson Toros of the Pacific Coast League, with whom he went 3-2 with a 4.47 ERA in 15 games before being dealt to Texas Rangers just after his 29th birthday in June, for a player to be named later. He pitched 4⅔ innings in three games for the Rangers and in 18 games for their Oklahoma City 89ers, before being released on waivers on July 8.

Schiraldi spent 1992 trying to get his arm back in shape, but when he threw for a scout and struggled, he knew it wasn’t to be. He went back to University of Texas to study and prepare for a coaching career. His mother told a reporter, “He always said, even when he was younger, that what he really wanted to do was coach.”17 Schiraldi started as a volunteer assistant at St. Michael’s Catholic School in Austin and as of 2015 had been the head coach there since 1997. His teams as of 2015 had earned two state championships, seven district championships, and 14 consecutive regional finals appearances.

In 2006 Lou Gorman and Bob Stanley were asked to compare another strong young Red Sox rookie reliever, Jonathan Papelbon, to Calvin Schiraldi and Roger Clemens. Both saw him as more reminiscent of Clemens. Stanley said that Schiraldi “went down the tubes” after the 1986 World Series loss. “I don’t think he was ever the same,” he said. “You’ve got to be able to roll with the punches.”18

Gorman did not pin the gradual decline to that one game. He echoed his own assessment from his own 2005 memoir. Of Schiraldi he’d written: “[The one factor that kept coming to mind was his lack of intensity.” He said of Clemens: “You had the feeling he would knock down his mother if it was necessary to win. With Schiraldi, I never had that feeling.”19

On the 25th anniversary of the 1986 World Series, Keith Olbermann wrote of Schiraldi’s graceful demeanor and of his work with young players: “Schiraldi has had an impact that merely getting the last out could never have afforded him.”20

Calvin and Debra had two children, a daughter, Samantha, and a son, Lukas, whom he coached at St. Michael’s. Lukas was a star high-school pitcher, like his father. He was an All-American at Navarro College and was drafted by the Washington Nationals, but also decided to go to the University of Texas instead. In 2015 he was with the Seattle Mariners’ Double-A team in Clinton, Iowa.

Sources

In writing this biography I made extensive use of the archives of the New York Times, Boston Globe, Boston Herald, Omaha World Herald, Richmond Times Dispatch, Rockford Register Star, San Diego Union-Tribune, and Dallas Morning News. I also consulted Mike Sowell’s 1995 book One Pitch Away and Lou Gorman’s 2005 book One Pitch from Glory.

Notes

1 Leigh Montville, “A Constant Vigil for Stopper’s Father,” Boston Globe, September 3, 1986.

2 Steve Sinclair, “Shockers Eliminate Top-Rated Longhorns,” Omaha World Herald, June 12, 1982.

3 Michael Kelly, “Penner Injury Bothered Team,” Omaha World-Herald, June 9, 1983: 38.

4 Peter Gammons, “Schiraldi and Clemens Reunited,” Boston Globe, November 14, 1985.

5 Tom Shea, “Schiraldi Gets High Maarks From Insider,” Springfield Union, November 14, 1985.

6 Joe Giuliotti, “Stanley Puts Finger on ’85 Woes,” Boston Herald, March 20, 1986.

7 Larry Whiteside, “Trade Said to Be Near,” Boston Globe, July 22, 1986.

8 John Powers, “To the (Schiraldi) Finish,” Boston Globe, October 7, 1986.

9 Dan Shaughnessy, “Schiraldi Gets His Turn — And Turns It Around,” Boston Globe, October 13, 1986.

10 Kevin Paul Dupont, “They Both Pitched In for Win,” Boston Globe, October 19, 1986.

11 John Powers, “Schiraldi Shoulders the Blame,” Boston Globe, October 28, 1986.

12 Dan Shaughnessy, “Schiraldi Carries Unwanted Burden,” Boston Globe, March 3, 1987.

13 Associated Press, “Smith Gets Five Hits in Cardinals’ Fifth Straight Win,” Times of Trenton (Trenton, New Jersey), June 12, 1989.

14 Nick Cafardo, “Red Sox’ Mo Vaughn Has Work to Do on Defense,” Stamford Advocate, February 11, 1990

15 Joe Giuliotti, “Clemens Feeling No Pain,” Boston Herald, August 11, 1990.

16 Joe Giuliotti, “Brumley Surges in Utility Role,” Boston Herald, March 24, 1991.

17 Tom Buckley, “Win Some…” The Alcalde (University of Texas alumni magazine), July-August 2006.

18 Gordon Edes, “Shades of Schiraldi?” Boston Globe, April 23, 2006.

19 Lou Gorman, One Pitch From Glory: A Decade of Running the Red Sox (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2005), 58.

20 keitholbermann.mlblogs.com/2011/11/10/calvin-schiraldi-sportsman/.

Full Name

Calvin Drew Schiraldi

Born

June 16, 1962 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.