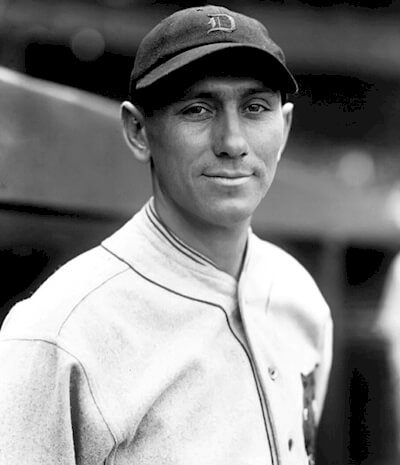

Johnny Neun

The once thick and perfectly groomed dark hair grew thin and gray over a professional career spanning a remarkable sixty-nine years. From 1920 to 1989, Johnny Neun served in the capacities of player, coach, manager, instructor and scout. Along the way, he earned a reputation as a great baseball mind, an excellent storyteller, and an outstanding human being.

The once thick and perfectly groomed dark hair grew thin and gray over a professional career spanning a remarkable sixty-nine years. From 1920 to 1989, Johnny Neun served in the capacities of player, coach, manager, instructor and scout. Along the way, he earned a reputation as a great baseball mind, an excellent storyteller, and an outstanding human being.

The youngest of five children born to John (a blacksmith) and Emelie Wenn Neun, John Henry arrived on October 28, 1900. The family was of German heritage, residing in a row house on South Potomac Street in East Baltimore. Johnny attended PS 83 in the city while participating in numerous sports around the Canton and Patterson Park areas.

Adults predicted a bright future for young Johnny as a teacher, writer or athlete. According to The Sporting News, “Little Johnny had more imagination than most boys his age and was adept at more activities than most of his playmates. By the same token, he had more ambitions, most of which were built around his unusual athletic ability.”1

For example, Neun became a founding member of the original Baltimore Soccer Club, serving as captain of the 1918-20 championship teams. Johnny also teamed with his pal Elmer Fody to win the Baltimore City tennis doubles championship in 1920.

As for baseball, young Johnny’s favorite player was the New York Highlanders left-handed first baseman Hal Chase. Being a natural lefty himself, Johnny gravitated toward playing that position and even learned to imitate Chase’s right-handed batting stroke, becoming adept enough to switch-hit during his professional career. According to John Steadman of The Sporting News, “His earliest recollection of professional baseball in Baltimore was going to a Federal League game in 1915. He paid ten cents to sit in the bleachers and watch Chief Bender of the Baltimore Terrapins, pitch against Eddie Plank of the St. Louis Terriers.”2

As a Baltimore City College student, Neun earned pocket money officiating high school soccer matches. However, by accepting a stipend of fifty cents a game he unwittingly placed himself in a professional category. The classification made him ineligible to play college baseball or participate in any other amateur sport.

Needing to replace the lost revenue, Johnny regretfully left college in 1920 to sign a contract with the Class D Martinsburg Mountaineers. As a professional ballplayer, the 5-foot-10, 175-pound Neun earned $175 a month while hitting Blue Ridge League pitching at a respectable .263 clip.

Neun returned to Martinsburg for the 1921 campaign, hitting a commendable .342. At season’s end, he returned home to complete his college courses while also coaching youth basketball and serving as president of the Maryland Referees Association.

Sold to the Class A Birmingham Barons in 1922, Johnny feasted on Southern League pitching, hitting an impressive .329. Returning to Birmingham in 1923, Neun hit .320 with 58 stolen bases. This warranted a promotion to Class AA St. Paul in 1924, where the young first baseman hit .353 and stole 55 bases. Neun’s strong performance was noticed by Detroit Tigers player-manager Ty Cobb.

Cobb considered his 1924 club to be a legitimate pennant contender despite an injury to veteran first-baseman Lu Blue, which was thought to hurt the team’s chances of capturing the flag. Cobb approached owner Frank Navin, suggesting the acquisition of Neun from St. Paul. Cobb later related the story to author Al Stump: “I wanted to shoot Navin. He claimed he couldn’t afford Neun at a fifty-five hundred selling price.”3 Cobb added, “I told Navin, if he was so cheap, he could take the fifty-five hundred out of my salary.”4 The Tigers ultimately obtained Neun in 1925 to serve as a pinch hitter and back-up first-baseman.

Cobb imparted his encyclopedic knowledge of base-stealing technique to Neun. Although never exceptionally fast, Johnny became more than competent on the base paths. The Detroit skipper quickly noted Neun’s quick mind and keen baseball sense. Cobb usually directed hitters and base runners from the third-base coaching box. In his absence, the skipper felt comfortable assigning Johnny to handle the duty. Neun hit .267 in 60 games for the fourth-place Tigers.

Johnny led the American League with 12 pinch-hits in 1926, batting an overall .298 in 97 games, but Detroit fell to sixth place in what became Cobb’s last season with the team. Years later, Neun commented to sportswriter Bob Maisel regarding his tenure with Cobb: “I didn’t find him that tough to play for. He didn’t offer too much to the younger players like me, but if you asked him something, he’d talk as long as you wanted to listen.”5

Former major-league player (and umpire) George Moriarity assumed the managerial reins of the Tigers in 1927. The club was occupying seventh place when the Cleveland Indians arrived to play a series in Detroit, spanning the Decoration Day holiday. Meanwhile, on Monday, May 30 at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, Chicago Cubs shortstop Jimmy Cooney had turned an unassisted triple play. According to a later story in Sports Illustrated, as morning broke on Tuesday, May 31, “Detroit players were having breakfast together and reading about Cooney’s unassisted triple play.”6 Johnny Neun rhetorically asked his teammates, “I wonder how long it will be before anybody makes another one.”7

Suiting up in the locker room, Neun studied several newspaper accounts of the story, mentally role-playing scenarios enabling a first baseman to accomplish such a feat. That afternoon, Johnny Neun indeed executed an extremely rare, game-ending unassisted triple play. At the time, it was the seventh such occurrence in baseball history and the second recorded by a first baseman, joining George Burns in 1923.

The game was a classic pitchers duel, pitting Detroit right-hander Rip Collins against the aptly named Cleveland left-hander Garland Buckeye. The hometown Tigers clung to a narrow 1-0 lead in the ninth inning, courtesy of a first-inning RBI single by Heinie Manush.

Cleveland was down to their final three outs when Glenn Myatt stepped up to pinch hit for Buckeye. Myatt lashed a sharp single over the head of shortstop Jackie Tavener. Charley Jamison followed by singling Myatt over to second.

Left-handed hitter Homer Summa then came up and smacked a wicked line drive. Neun gloved it for the first out. Jamison started retreating back to first, and Neun tagged him for out number two. Myatt, believing the liner was a hit, had left second en route to third; his hurried attempt back to second was foiled as Neun outraced him to the bag, completing the unassisted triple play. The hometown crowd cheered wildly as the Tigers captured an exciting 1-0 victory.

“Neun accepted his honors with becoming modesty,”8 said Clifford Bloodgood in a 1936 article in Baseball magazine. Johnny remarked to the press: “I got a little more publicity on it, because the play came at the psychological moment; in the ninth inning with the score 1-0 in our favor.”9 The Detroit News reported, “Johnny Neun is not the only first baseman in history to make an unassisted triple play, but Neun’s play against Cleveland on May 31, 1927, carried more dramatic effect than any other ever made in baseball.”10

As the years passed, elite storyteller Johnny Neun delighted in flavoring variations of the tale. A popular version stated that shortstop Jackie Tavener urged him to throw the ball for an easier third out. Neun embellished the tale by purportedly replying, “No, I’m running it into the Hall of Fame.”11 Perhaps he simply forgot that the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown didn’t exist until nine years later, in 1936. The ball and the glove Neun used that day were bronzed, and are now part of the collection at the museum.12

As an encore, Johnny stole five bases on July 9, 1927, in a contest against the New York Yankees. Four days later, he stole home twice (one at each end of a double-header) against the Washington Senators. Neun commented regarding his philosophy on the base-paths, “Base running consists of paying minute attention to detail, watching the pitcher for tip-offs in his delivery, knowing just how far you can stray from the bag in safety, rounding the corners without too much loss of ground and keeping a book on the outfielders, the ones that can throw and the ones that can’t.”13 The Moriarity-led Tigers finished fourth in 1927, as Neun hit .324 in 79 games.

An appendicitis attack limited Johnny’s playing time in 1928 to only 36 games. After he hit an anemic .213 the Tigers placed the first baseman on waivers, leading to his acquisition by the AA Baltimore Orioles.

Playing close to home in 1929 agreed with Johnny, as he hit International League pitching at a .330 clip. His numbers prompted the Boston Braves to draft him from the Orioles, on October 7, 1929. With the Braves in 1930, playing under the tutelage of skipper Bill McKechnie. Johnny hit National League pitching at a .325 pace in 85 games while adequately backing up veteran first baseman George Sisler.

Returning to his hometown, Johnny resumed his offseason avocation as sportswriter/soccer editor at the Baltimore Evening Sun. In the newspaper office, he met Harminia Grae Warehime, a co-worker from the advertising department; the couple married in 1930.

Returning to Boston for a second season in 1931, Johnny slumped to .221 in 79 games. The Braves sold his contract to the New York Yankees on December 1, 1931. Although he and Braves manager McKechnie parted company, their paths would cross again.

The Yankees were aware of Johnny’s baseball acumen, his fine leadership skills, and ability to project intelligence and authority when he spoke. The New York club planned to use him as a player-coach while grooming him for a managerial role. Assigned to the International League Newark Bears (AA) in 1932, Johnny hit .341 in 159 games. Returning to Newark in 1933, he hit .309 as a player-coach, followed by a .255 mark in 1934.

For the 1935 season the Yanks assigned Neun to Class C Akron of the Mid-Atlantic League. In this assignment he was promoted to the roles of field manager and general manager. Additional responsibilities included scheduling travel, arranging accommodations and coordinating bus routes. Following night games, it was not unusual for the team to travel several hundred miles.

Years later, Johnny reflected on those days and the joys of bus travel: “The only privilege the manager had at Akron was to sit in the front seat of the bus. The fellow who sat down with me always seemed to be the pitcher who got banged for seven or eight runs in the first inning. While the manager tried to catch a snooze, a young pitcher would nudge the skipper and ask: what was I doing wrong out there?”14

Neun developed a pantomime routine illustrating the impossible task of getting a good night’s sleep while traveling by bus or train. Performed using two chairs and a suitcase as props, the act delighted audiences and was considered good enough to make a professional entertainer envious. Over the years, he fine-tuned the routine and used it to entertain hospitalized troops during the Second World War

Moving up to the Piedmont League with the class B Norfolk Tides, Neun won the pennant in 1936 and finished second in 1937, but won the postseason playoffs. This warranted the prestige of succeeding Newark Bears skipper Ossie Vitt, following the team’s remarkable 1937 season in which it won 109 games. Under Neun’s leadership, the club repeated as International League champs in 1938, despite losing several key players to the major leagues. Neun remained the Bears manager until the end of the 1941 season.

Johnny captured another pennant in 1942 as skipper of the Kansas City Blues in the Class AA American Association. That role continued until 1944 when he joined the Yankees coaching staff, replacing the recently retired Earle Combs. Johnny’s entree to the parent club was accompanied by his reputation as “an intense student of the game, a hard worker; but regularly lapses into the role of comedian. He is a hard loser; has always fought to win and instills the will to win in his players.”15

An unofficial duty assigned to Neun, not listed in his job description, was accompanying Yankee manager Joe McCarthy on speaking engagements. McCarthy disliked addressing audiences at civic meetings, club events and hospital visits. Marse Joe preferred turning the festivities over to Johnny — “who’d entertain with a ready smile, winning personality and gift for storytelling.”16

On May 26, 1946, McCarthy informed Yankees President/GM Larry MacPhail of his intention to step down as skipper, allegedly following doctor’s orders. Coach Bill Dickey took over as the manager, but didn’t last the season. Dickey’s September exit opened the door for Neun to serve as the Yankees’ interim manager; Bucky Harris had already been signed to run the club in 1947.

Meanwhile in the National League, Cincinnati Reds GM Warren Giles was feeling the heat from upper management over losing seasons and a dwindling fan base. Manager Bill McKechnie had run the club from 1938 to 1946, winning two pennants and one World Series. But McKechnie’s fate was sealed following a seventh-place finish in 1945 and sixth place in 1946. McKechnie respected Neun as an excellent baseball man and recommended his former player to Giles as his replacement. Giles inquired about Neun’s availability and received a thumbs-up from the Yankees.

The Cincinnati Reds’ spring training site in 1947 was Tampa, Florida. Neun, the new skipper, had barely unpacked his bags when he reinstituted a training technique from his playing days called the sliding pit. “If I can get this club to run, if I can get it to fight and hustle through every game, the rest of my job will pretty nearly take care of itself.”17 Staff ace Ewell Blackwell posted an exceptional 22-win season, leading the team to fifth place and a 73-81 record.

The 1948 season became a different story, as discontent festered in the Reds’ clubhouse. Temperamental shortstop Eddie Miller was the primary cause, annoyed by Neun’s jockeying of positions in trying to find a winning combination. Arm woes affected staff ace Blackwell, further contributing to the club’s fall to seventh place. At such times skipper ultimately pays the price; one hundred games into the season, Neun was replaced by Bucky Walters. The club had a record of 44-56 under Johnny’s leadership. Neun later admitted not being fond of managing, claiming it overtaxed his nervous system.

Returning to the Yankees organization in 1949, Neun served as a scout and player-development specialist. Johnny was appointed director of scouting potential World Series opponents; he played down his importance in that role. “For 16 years, I wrote the book on the Yankees’ World Series opponent. I was part of a team that did the scouting, but I actually wrote the book because as an ex-sportswriter, I was the only one who knew how to use a typewriter.”18 Yankees outfielder Tommy Henrich commented regarding the notes compiled on the 1950 Phillies: “It was the best scouting job I’ve ever seen. I had to marvel at the book they had on the Philly hitters. It was detailed and just about perfect.”19

Neun left the Yankees organization in 1969 to head the Kansas City Royals’ innovative baseball academy. Young players received thorough instruction as Neun painstakingly taught them to see and do things others missed. When he died Albert Schlsted of the Baltimore Sun memorialized him, saying, “His ability to think in today’s version of the game is the most interesting thing about him. It’s amazing and rare how his outlook has changed along with baseball. All of which gives him a special quality of relating to the players.”20

Neun went on to become an instrumental part of the Milwaukee Brewers system as a scout and instructor. Each spring he’d travel from Baltimore to the Brewers’ training camp, suit up upon arrival and begin working with the young players, right up to the age of 88.

Brewers general manager Harry Dalton commented: “He was one of the finest men I have known. He took exceptional care of himself, which is why he was coaching in our minor-league camp. He never drank or smoked and wouldn’t allow himself to put on weight. He respected modern players and was never jealous of the salaries. Truly a joy to know, respect and yes, even revere.”21

A medical exam in February 1990 revealed that Johnny was suffering from pancreatic cancer. After a brief hospital stay, he passed away on March 28, 1990, at the age of 89. He was buried at Immanuel German Lutheran Cemetery in Baltimore. Johnny’s beloved wife, Harminia, had passed away in Baltimore on December 6, 1974. The couple had no children.

Contemporaries of Johnny Neun never heard him refer to the game, or anyone connected with it, in negative terms. “How could I ever say anything bad about baseball?” he said. “I’m just a little guy from Baltimore who has been able to have a good life because of this great game. Everything I have I owe to baseball. I’ve never done anything else. It has given me a great deal.”22 “And it can be said without even the slightest doubt, that everything baseball gave to Johnny Neun, he gave back.”23

Sources

Thanks to the National Baseball Hall of Fame for sharing the content of Neun’s player file. Vital information was obtained from baseball-reference.com, retrosheet.org, sabr.org/bioproject and ancestry.com. The Sporting News, accessed through sabr.org, also provided important details.

Notes

1 Michael F. Gavin, “Neun Couldn’t Decide on Playing, Coaching, Teaching or Writing.” The Sporting News, December 21, 1939.

2 John Stedman, “Johnny Neun Fundamentally Fresh at 84.” The Sporting News, April 4, 1985.

3 Al Stump, Cobb, (Algonquin, Chapel Hill, 1996), 353.

4 Ibid.

5 Bob Maisel, “Johnny Neun: baseball man all the way,” April 1, 1990.

6 Carl Lundquist, “Neun Unassisted Triple Play revisited Forty Years Later.” Sports Illustrated, May 29, 1967.

7 Ibid.

8 Clifford Bloodgood, “Thirty Seconds Made Him Famous,” Baseball Magazine, December 14, 1936.

9 Ibid.

10 Lundquist.

11 The Cumberland (Maryland) News, June 5, 1980.

12 Ibid.

13 Dan Daniel, New York World-Telegram, March 16, 1949.

14 HOF Clipping, Heywood Hale Broun, 1948.

15 Paul Broderick, “Seven League Boots,” The Baltimore Sun, August 24, 1947.

16 Ibid.

17 Dan Daniel, “Sliding Pit Again A Training Factor.” The New York World-Telegram, March 28, 1947.

18 Jim Elliot, “Neun Keeps ‘em Laughing,” The Baltimore Sun, July 24, 1965.

19 Tommy Henrich, “Series Credit to Scouts Neun, Skiff,” New York World-Telegram, October 9, 1950.

20 Albert Schlstedt, “Neun 89, Dies.” The Baltimore Sun, March 29, 1990.

21 Bob Maisel, “Johnny Neun: Baseball Man All the Way,” The Baltimore Sun, April 1, 1990.

22 Ibid.

23 John Steadman, Days in the Sun (Baltimore Sun Co., 2000).

Full Name

John Henry Neun

Born

October 28, 1900 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

Died

March 28, 1990 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.