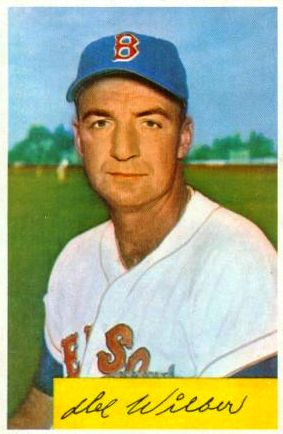

Del Wilber

Del Wilber was a consummate organization man. A role player throughout his career, his shining moments were brief, but his life, his baseball career, and the friendships he formed within the game were long and lasting. Wilber played in the military and in the minor leagues, then toiled as a journeyman catcher for the St. Louis Cardinals, Philadelphia Phillies, and the Red Sox in the late 1940s and early ’50s. He later served several organizations as a bench coach, minor league manager, instructor, scout, and – for one day — a major-league manager.

Del Wilber was a consummate organization man. A role player throughout his career, his shining moments were brief, but his life, his baseball career, and the friendships he formed within the game were long and lasting. Wilber played in the military and in the minor leagues, then toiled as a journeyman catcher for the St. Louis Cardinals, Philadelphia Phillies, and the Red Sox in the late 1940s and early ’50s. He later served several organizations as a bench coach, minor league manager, instructor, scout, and – for one day — a major-league manager.

As a player, he hit just 19 home runs in eight seasons, but is best remembered for the night he slugged three in one game. On August 27, 1951, Wilber became the only player in major-league baseball history to hit three home runs in three at-bats and to score and drive in all of his team’s runs, in a 3-0 Phillies victory over the Cincinnati Reds at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. As a member of the Boston Red Sox in 1953, he remarkably managed to finish the season with more runs batted in (29) than hits (27). A 6-foot-3, 200-pound right-hander, Wilber batted .242 and drove in 115 runs in his 299-game major-league career.

Loyal and well liked, “Babe” Wilber formed lasting friendships with many of his teammates. He was also known for his unique artwork; he decorated baseballs with cartoons and comments to commemorate the accomplishments of his teammates, complete with line scores and game highlights.

As a manager, “Skip” Wilber won an American Association championship and two Pacific Coast League championships, but is best remembered for a one-game stint in the majors. Named interim manager after impetuous Texas owner Bob Short fired Whitey Herzog, Wilber guided the Rangers to a come-from-behind 10-8 victory over the Oakland Athletics on September 7, 1973, but was replaced by Short the very same night in favor of mercurial Billy Martin. Though disappointed, Wilber stoically returned to his minor-league duties and cemented his reputation as an organization man. He continued to manage in the minors, and then served another decade as a scout before he left the game.

Delbert Quentin Wilber was born on February 24, 1919, in Lincoln Park, Michigan, outside Detroit. He was the second son born to Delbert, a garage mechanic who later ran a trucking company, and Mary Philomena (Quandt) Wilber. Their first child, Delmar, had died a year earlier at the age of six months after a short illness.

The younger Delbert’s middle name honored Quentin Roosevelt, the son of former President Theodore Roosevelt; Quentin was an aviator shot down and killed in combat during World War I. Del’s mother, Mary, whom the family called Edna Ma, dubbed her new son Babe, a nickname that stuck through his life. A sibling, Don, was born on the same date two years after Del, and the two brothers grew up in Lincoln Park, a bedroom community that housed workers from the burgeoning Detroit automobile industry.

Del Jr. attended William Raupp School in Lincoln Park; then transferred to St. Henry’s Catholic School. St. Henry’s didn’t participate in sports, and after a year, the youngster persuaded his parents to allow him to return to William Raupp, where he played basketball, baseball, and soccer. Wilber later attended Lincoln Park High School, where he earned three letters in football, four in basketball, and four in baseball before he graduated in 1937.

That summer, Wilber went to work in the stockroom at Ford Motor’s immense River Rouge assembly plant in neighboring Dearborn, where he unpacked crates of car jacks, hubcaps, and wheels, and played industrial league basketball. In July, he read a newspaper brief about a three-day tryout camp in Springfield, Illinois, for the San Antonio Missions, a St. Louis Browns farm club. Wilber and a friend traveled 450 miles each way in a Ford Model A to participate in the camp.

Wilber was impressive enough to land a minor-league contract for the 1938 season. He joined the Findlay Browns of the Class D Ohio State League, and hit .304 in 97 games as a 19-year-old. In 1939, the young backstop batted .332, led the league with 157 runs batted in, and guided the renamed Findlay Oilers to the regular-season title.

After the season, the Browns’ crosstown rival, the St. Louis Cardinals, selected Wilber in baseball’s minor-league draft and assigned him to the Springfield (Missouri) Cardinals of the Class C Western Association, where he hit .308 in 113 games in 1940. The next year, the 22-year-old backstop moved up to the Columbus (Georgia) Red Birds of the Class B South Atlantic League. He hit .262 with 10 home runs as a catcher and third baseman, and was tendered a major-league contract for 1942 by the Cardinals.

Wilber’s plans, like those of many of his generation, were sidetracked after the December 7 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. On February 4, 1942, Wilber entered the Army at Fort Custer, Michigan. He was assigned to the Jefferson Barracks Army Air Force base at Lemay, Missouri, near St. Louis, where he trained to become a glider pilot and served as the baseball team’s player-manager. Jefferson Barracks played against other military teams, and Wilber later recalled that he caught in exhibition games against Negro League teams that included Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson.

Wilber rose to the rank of drill sergeant and transferred to Miami Beach, Florida, in October 1942 to attend Officer Candidate School. He earned his commission as a lieutenant in early 1943, and was assigned to the San Antonio (Texas) Aviation Cadet Center at the preflight school at Kelly Field. Wilber spent the duration of the war at Kelly Field, where he met Edna Mae “Taffy” Bennett, a civilian personnel department employee at the base, who had recently been named Miss Air Force San Antonio. They were married on December 21, 1943.

Wilber was a physical-education instructor and managed the air base squad that featured outfielder Enos Slaughter and pitcher Howie Pollet, both members of the Cardinals’ 1942 world championship team. Wilber and Slaughter each hit 13 home runs in 1944 to lead the cadet center’s Warhawks to the San Antonio Service Baseball League playoffs. In the championship series, the Warhawks defeated the Randolph Field Ramblers, managed by University of Texas coach Bibb Falk, and led by future Boston Red Sox hurler Dave “Boo” Ferriss, two games to one.

Before the 1945 season, Slaughter and Pollet embarked on a tour of US bases in the Pacific, while Wilber stayed in San Antonio. On May 8, Wilber and three teammates were accused of “roughing up” umpire Nemo Herrera. Wilber voluntarily suspended himself for four games, but Herrera demanded that all four of the Warhawks involved be officially penalized. Two days after the incident, the local Army Athletic Council suspended Wilber for 12 games and each of the players for 10.

World War II ended in September 1945 and Wilber, who had attained the rank of captain, was discharged from the Army Air Forces the following February, in time to attend spring training with the Cardinals, four years after his country’s call to duty had interrupted his career.

He made his belated major-league debut at the age of 27 on Sunday, April 21, 1946, in a 7-6 win over the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field. Wilber entered as a defensive replacement at catcher in the bottom of the seventh, and after Cardinals’ relief pitcher Murry Dickson struck out the side, Wilber was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the eighth. Wilber made three additional early-season appearances, batted five times without a hit, and was sent down to the Triple-A Columbus (Ohio) Red Birds. He played in 101 games for Columbus, managed by former Cubs pitcher Charlie Root, and batted .263 with seven home runs.

Wilber returned to St. Louis and collected his first major-league hit in his first at-bat of the 1947 season. On April 17, Wilber doubled off lefty relief pitcher Kent Peterson when he pinch-hit in the sixth inning of Cincinnati’s 9-4 win over the Cardinals at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. He spent the entire season in the big leagues with the defending world champion Cardinals squad that included Pollet, Slaughter, Stan Musial, and Red Schoendienst. Wilber batted .232, clubbed eight doubles and a triple, and drove in 12 runs in 99 at bats as the Cards’ third catcher, behind the platoon of right-handed-hitting Del Rice and left-handed-hitting Joe Garagiola. Cardinals manager Eddie Dyer, who wasn’t satisfied with any of his three catchers, said, “One can’t hit, one can’t catch, and one can’t throw.” When Garagiola was injured in 1948, it was veteran Bill Baker who backed up Rice. Wilber batted .190 and drove in 10 runs in 27 games.

In 1949, at the age of 30, Wilber collected one hit in four at-bats before the Cardinals dispatched him to serve as player-manager for the Houston of the Class A Texas League to replace Johnny Keane. Wilber guided the Buffaloes to a 60-91 record, good for seventh place, batted .309 with five home runs in 89 games, and allowed just two hits in five innings in his only career appearance on the mound.

In 1950, he followed Keane to Rochester, the Cardinals’ Triple-A affiliate, batted 440 times in 123 games, collected 41 extra-base hits, including 11 home runs, and batted .295 to help lead the Red Wings to the International League regular-season pennant. After Rochester fell in the finals of the league playoffs, St. Louis left the veteran catcher unprotected, and the Philadelphia Phillies plucked him in the minor-league draft on November 16.

He spent the offseason with the Habana Leones (Havana Lions) of the Cuban Winter League, a team managed by Mike Gonzalez that featured knuckleball pitcher Hoyt Wilhelm. Wilber batted .247 with three home runs in 54 games.

In the spring of 1951, he joined the Phillies and, at the age of 32, embarked on his finest season. He set major-league career highs in games played (84), hits (68), triples (3), runs scored (30), and runs batted in (34) and sported his best batting average at .278. He also enjoyed the biggest moment of his career, the three-home-run game on August 27. Earlier that day, he and Taffy had brought newborn daughter Cynthia home from the hospital. That night, in the second game of a doubleheader, he fought off a bad cold and homered in three consecutive at-bats, all off Cincinnati starter Ken Raffensberger.

Wilber appeared in just two games for the Phillies in 1952 then was dealt to the Boston Red Sox on May 12. He batted .267 in 47 games for the Red Sox, hit three home runs, and drove in 23 runs in 135 at-bats. He also recorded the only stolen base of his big-league career.

In 1953, Wilber enjoyed an unusual and efficient season when he collected 29 runs batted in with just 27 hits. Of the 27, six were doubles, one was a triple, and seven were home runs. He played in a pair of games at first base, the only time he appeared in the major leagues at a position other than catcher. Wilber earned folk-hero status in Boston when he clubbed pinch-hit home runs on May 6 and 10, and smacked his third of the year on May 20, a two-out, 14th-inning solo shot at Fenway Park off relief pitcher Don Larsen to beat the St. Louis Browns. He hit another in the nightcap of a July 4 doubleheader at Boston, his fourth pinch-hit home run of the season, one short of the AL record of five established by Boston’s Joe Cronin in 1943.

A year later, at the age of 35, the veteran backstop batted just .131 with one home run in 24 games. On September, 19, 1954, in a 6-2 win at Griffith Stadium, Wilber collected two hits, including a triple off Washington’s Camilo Pascual, in the final at-bat of his major-league career. On December 14, Wilber was traded to the New York Giants for infielder Billy Klaus, and was assigned to the Giants’ Triple-A farm club, the American Association’s Minneapolis Millers. Rather than report to the minor-league club, Wilber asked for his release, and after it was granted, secured a job as bench coach and emergency catcher (he was not called upon) for White Sox manager Marty Marion, his old Cardinals teammate, on January 25, 1955. Chicago finished third in the AL that year and again in 1956, and Wilber was dismissed when Marion was replaced by Al Lopez.

He served as a scout for Baltimore the next year, then managed the Orioles’ Triple-A farm club, the Louisville Colonels, to a 56-95 record and an eighth-place finish in the American Association in 1958. At the age of 39, he made 11 appearances – the last of his playing career – and in 10 at-bats, collected three hits, one a home run. After the season, the Orioles, Louisville, and Wilber all went their separate ways.

Two months into the 1959 season, Wilber returned to the dugout, back in Houston, where he managed a Triple-A level team with no major-league affiliation. The Buffs had stumbled to a 29-41 start in American Association play under player-manager Rube Walker; they were no better under Wilber, and posted a 39-63 record the rest of the way. The Buffs finished with the worst record in the 10-team league, and Wilber was dismisssed.

Never out of baseball for long, Wilber piloted Washington’s Triple-A affiliate, the Charleston (West Virginia) Senators, to a 65-88 record, sixth best in the eight-team American Association, in 1960. Wilber remained in the organization when the Senators relocated to Minnesota; and from 1961 to 1969, managed the Twins’ Florida Instructional League team and served as a “super scout,” or scouting supervisor. The Twins boasted a strong farm system in the 1960s; among the players Wilber developed were Rod Carew and Tony Oliva.

Before the 1970 season began, Ted Williams, Wilber’s old Red Sox teammate and friend, learned that he had not qualified for a full pension because he had fallen 85 days short of the required nine years’ service in the major leagues. A year earlier, Williams had earned Manager of the Year honors when he led the hapless Washington Senators to a winning season. Williams made his old buddy the bullpen coach; together they endured the new Nats’ slide into to the AL East cellar. A full pension in hand, Wilber returned to the minor leagues and embarked on a run of minor-league success in 1971 at the age of 52.

He managed Washington’s Triple-A affiliate at Denver to a 73-67 record and an American Association West Division title in 1971. The Bears, led by Lenny Randle and Richie Scheinblum, trailed East Division champion Indianapolis (the Triple-A affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds) three games to two in the best-of-seven series, and were forced to play the final two games of the series in one day, because the Denver Broncos were scheduled to kick off their National Football League season at Mile High Stadium the next day. Denver won both ends of a day-night doubleheader to capture the league title. Forced to play the entire Little World Series on the road, the Bears extended International League champion Rochester to seven games before the Red Wings prevailed.

Denver slipped to a sixth-place finish the following year, and when owner Bob Short transferred the second Senators franchise to Texas, he also shifted the franchise’s Triple-A affiliation to Spokane of the Pacific Coast League. Wilber went with the team to the Pacific Northwest and managed the Indians, led by Bill Madlock and Lenny Randle, to an 81-63 record, first place in the West Division, and to a three-game sweep of East Division champ Tucson in the finals.

The day after the PCL season ended, Short summoned Wilber to Texas for meetings, and named him interim manager of the Rangers. “Dad had just won the Pacific Coast League championship with his Spokane Indians (his third Triple-A championship in four years), and was in Arlington for meetings with the big club when he got the news,” his son Bob wrote; “so he headed for the clubhouse, saw WILBER on the back of uniform 45, and filled out his lineup card, making sure to start a couple of his favorite players from the Spokane team, who had also just been ‘called up to the show.’ Those two guys (Larry Biittner and Bill Madlock) got five hits between them, the Rangers came back from a 6-1 deficit to win, 10-8, and Del Wilber was 1-0 as a major-league manager.”

Wilber barely had time to celebrate the victory. Minutes after the game ended, Short conducted another press conference and abruptly yanked the rug out from under Wilber’s feet. “At the conclusion of the game, the Rangers announced they had hired Billy Martin, effective immediately, so my dad finished his major-league managing career with an undefeated 1-0 record,” Bob Wilber wrote. “As Casey Stengel used to say, ‘You could look it up…’ As a high-school senior, I was pretty crushed that Dad didn’t get a better shot at managing in the majors, but he took it much better than I did. As he said, ‘Son, I’ve been in this game all my life. It wasn’t a bad ride.’ I guess it wasn’t.”

Still, Wilber was disappointed. “I can’t come up with a better percentage,” he told the Boston Globe at the time, “but I’d like to see what I can do over a period of time.” Always an organization man, he returned to Spokane and quietly led the Indians to a 78-64 record, another West Division title, and another three-game sweep of the East Division winner, this time Albuquerque, in the 1974 PCL Playoffs.

With little talent on the roster, Spokane slumped to a 64-78 record and a third-place finish in the PCL West Division in 1975, and the franchise elected to terminate its agreement with the Rangers.

Wilber rejoined the Minnesota organization and reprised his role as a scout and Instructional League manager in 1976 and 1977. He was named to replace his friend Cal Ermer as manager of the Twins’ Triple-A affiliate at Tacoma in 1977, but the PCL Twins started slowly, and posted just a 40-49 record before he in turn was replaced by one of his players, future Minnesota manager Tom Kelly, in June.

That stint was Wilber’s finale as a minor-league manager after a career that spanned all or parts of 10 seasons that touched the 1940s, ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. Though he never returned to the dugout, Wilber worked in baseball for another decade as a scout for the Oakland Athletics and Detroit Tigers, until he retired from baseball in 1986, at the age of 67.

Wilber and his wife, Taffy, who had worked for KMOX radio and in the Cardinals’ front office in the 1960s, continued to make their permanent home in the Kirkwood section of St. Louis, where they had raised five children during Del’s nomadic career. In retirement, Wilber maintained his longtime friendships with his old teammates and enjoyed the hero worship and perks accorded a former major leaguer. He attended Cardinals alumni functions and was recognized as a minor celebrity.

In his final years, while Taffy suffered with Alzheimer’s disease, Wilber endured a variety of ailments that included a broken wrist, a hip that required replacement, prostate, lung, and bone cancer, and congestive heart failure. During the final year of Wilber’s life, the couple moved from their St. Louis area home to St. Petersburg, Florida, near their son Rick. He documented that last year in My Father’s Game, an insightful and emotional journal more about the struggles and frustrations of caring for aging, agitated parents than baseball biography.

On July 18, 2002, at the age of 83, Del Wilber died in St. Petersburg. His death came just two weeks after the passing of Ted Williams and a month before the death of Enos Slaughter.

Wilber was survived by Taffy, his wife of 59 years; their three sons, Del Wilber Jr. of McLean, Virginia, Bob Wilber of Woodbury, Minnesota, and Rick Wilber of St. Petersburg, Florida; two daughters, Cynthia Wilber of Palo Alto, California, and Mary Lynn (Wilber) Smith of Orlando (now Sarasota), Florida; and 10 grandchildren. All three of his sons were collegiate athletes, Del Jr. and Bob played pro baseball; and Cynthia and Rick both authored books in which their father was remembered.

“Dad led a long and often charmed life,” Rick Wilber wrote. “He’d been a friend and teammate of the players and coaches of several generations of ballplayers from the early 1940s to the mid-1980s when he retired. He’d hit home runs off Bob Feller [not in a major-league game], caught fastballs from Robin Roberts, coached Rod Carew, been a good friend of Stan Musial and Ted Williams and Joe Garagiola and dozens of others.”

Former Cardinals second baseman and manager Red Schoendienst paid tribute to Wilber’s abilities as an organization man. “He was a good organizer,” Schoendienst told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch after his old teammate’s death. “He was a very good guy on the team. He was more or less second-string, but never complained about anything. He did what he was supposed to do.”

Sources

A special thanks to Bob Wilber, Del’s son.

Bullock, Steven. Playing for Their Nation: Baseball and the American Military during World War II. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Garagiola, Joe. Baseball is a Funny Game. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1960.

Gilbert, Bill. They Also Served, Baseball and the Homefront, 1941-45. New York: Crown Publishing, 1992.

Kahn, Roger, and Al Helfer, eds. The Mutual Baseball Annual 1954. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1954.

Nowlin, Bill, ed. Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (Almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948. Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2008.

Spatz, Lyle, ed. The SABR Baseball List & Record Book: Baseball’s Most Fascinating Records and Unusual Statistics. New York: Scribner, 2007.

Wilber, Cynthia, ed. For the Love of the Game: Baseball Memories from the Men Who Were There. New York: William Morrow and Company Inc., 1992.

Wilber, Rick. My Father’s Game: Life, Death, Baseball. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., Publisher, 2008.

The Sporting News.

Gary Bedingfield’s Baseball in Wartime website.

1920 United States Census.

1930 United States Census.

Proquest Historical New York Times.

www.minors.sabrwebs.com – Society for Baseball Research Minor Leagues Database.

www.bioproj.sabr.org/bioproj.com.

www.aviewfromthecheapseats.com

www.spokaneindiansbaseball.com

http://www.nhra.com/blog/wilk/

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Delbert Quentin Wilber

Born

February 24, 1919 at Lincoln Park, MI (USA)

Died

July 18, 2002 at St. Petersburg, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.