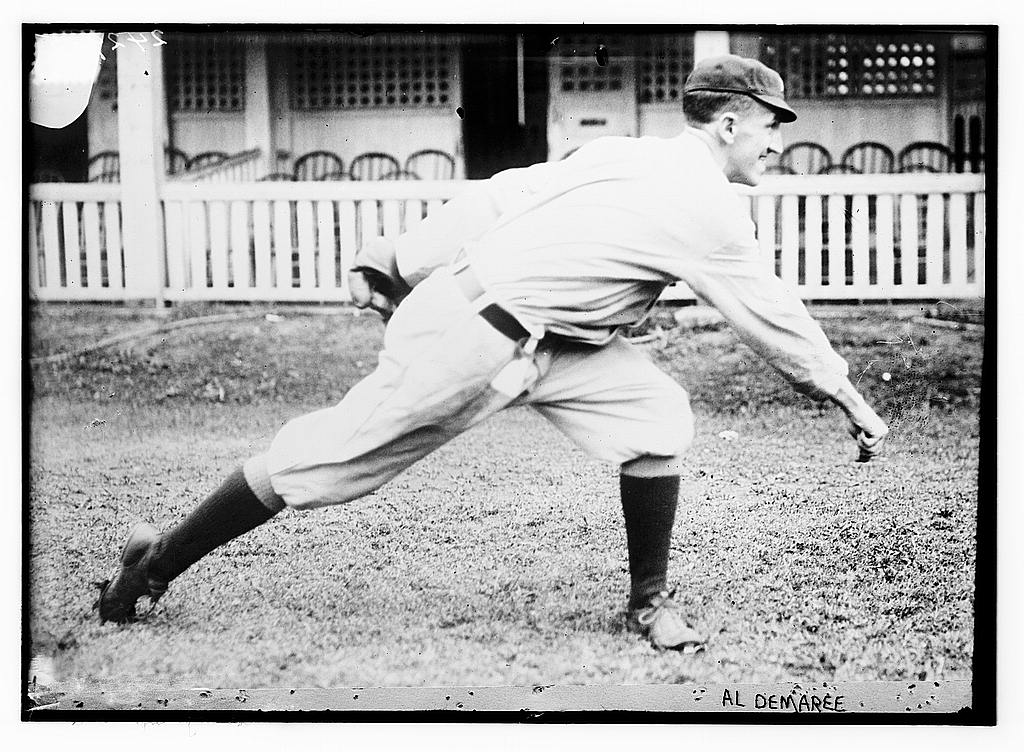

Al Demaree

“He has nothing but a little curve and confidence,” Giants manager John McGraw said of his rookie pitcher Al Demaree in 1913.1 Yet after a late arrival to the majors, the right-hander contributed to four pennant-winning staffs over an eight-year career. Demaree also chronicled baseball, with humor and insight, as a cartoonist for several decades. Indeed, he may have been the most widely read major leaguer in the 1920s and 1930s.

“He has nothing but a little curve and confidence,” Giants manager John McGraw said of his rookie pitcher Al Demaree in 1913.1 Yet after a late arrival to the majors, the right-hander contributed to four pennant-winning staffs over an eight-year career. Demaree also chronicled baseball, with humor and insight, as a cartoonist for several decades. Indeed, he may have been the most widely read major leaguer in the 1920s and 1930s.

Albert Wentworth Demaree was born on September 8, 1884, in Quincy, Illinois. He was the first of Albert and Ella Demaree’s two children. Brother Eaton arrived in 1888. The boys’ father worked in the newspaper business, as a typesetter and printer. By the turn of the century, the family lived in Chicago.

As a pitcher, Al Demaree was a late bloomer. He began in Chicago’s sandlots, and not until his “phenomenal showing” for Jimmy Ryan’s semipro Lawndale squad in 1907 did he attract attention.2 In 1908 Ryan brought Demaree along when he assumed the helm of the Southern Association’s Montgomery Senators. But in spring training, Ryan became convinced the twirler wasn’t ready for such fast company, and dealt him to the Columbus Discoverers of the Cotton States League.3

Eaton also pitched, and for several years traveled in the same circles as his older brother, leading to some record-keeping confusion. Both pitched for Columbus in 1908.4 Only Al interested George Stallings, then managing the Eastern League’s Newark Indians. Stallings picked him up, and Demaree joined Newark at the end of the season.5

Stallings moved up to manage the New York Highlanders in 1909. But like Ryan, he felt the pitcher wasn’t ready for advancement.6 Demaree signed with the South Atlantic League’s Savannah Indians. As the circuit’s season wound down, Chattanooga, looking for pitching assistance in the championship series versus Augusta, reportedly forwarded money to Demaree so he could buy his release from Savannah. Demaree did so, joined Chattanooga, and clinched the league championship in Augusta on September 20. “Maddened” Augusta fans swarmed the field afterward, and Demaree was “roughly used” before escaping to safety.7

In 1910 Demaree stayed with Chattanooga.8 He began 1911 in Tennessee as well, then was dealt to Mobile in June. Over these two years, he compiled a 26-26 record. As the 1912 season dawned, there was little indication that 27-year-old Demaree would advance beyond the high minors.

But Demaree opened the 1912 campaign with 37 consecutive scoreless innings,9 and finished it with a 24-10 record. McGraw secured rights to the pitcher from his former scout, Mobile manager Mickey Finn.10 Believing Mobile had a chance for the pennant, Finn didn’t part with Demaree until early September.11 By then the Giants were cruising to a pennant of their own. McGraw waited until September 26 to throw his new find into game action. Demaree shut out Boston in the second game of a doubleheader, officially clinching the NL flag. McGraw claimed it was the “finest work he had seen done by a newcomer in 20 years of base ball.”12 Demaree had arrived too late to be eligible for the World Series, and only pitched batting practice as the Red Sox defeated the Giants.

A “most awkward” delivery defined Demaree’s pitching, and its refinement may explain his 1912 breakthrough.13 First, he thrust his right hand into his hip pocket, where he stashed powdered rosin, and covered “the tips of his first two fingers of his pitching hand” with the substance.14 Then came, Damon Runyon wrote, “that jerky motion, which seems to be entirely from the elbow, and which gives the impression that he has a perennial sore arm.”15 The delivery finished inwards. “He pitched out of his own background,” Art Fletcher recalled; “that is, he sort of pushed the ball out in front of him — didn’t let go of it until it came at you out of the letters of his shirt.”16 “Al Demaree delivered a ball to the batter exactly as if he was putting the shot,” Honus Wagner added, “it was mighty hard to figure what he was doing.”17

Demaree mixed fastballs and off-speed pitches, but was best known for his curveball, which he effectively draped over the outside part of the plate. Sportswriters routinely disparaged his stuff. He lacked, one reporter opined, “enough speed to break a worn-out shingle,” and references to his “dinky curve” abounded.18 Yet Demaree was a determined competitor, and his face broke into a canny, toothy smile as he faced batters.

In 1913 McGraw used Demaree behind his workhorses: Christy Mathewson, Rube Marquard, and Jeff Tesreau. These three won 20-plus games apiece. Demaree went 13-4 with a 2.21 ERA. The Polo Grounds faithful called him “Steamer Al,” an affectionate nickname Runyon gave him, based on Demaree’s fondness for cigars.19

Giants fans also followed Demaree the cartoonist in the sporting pages. His path to the profession likely stretched back to childhood and the influences of his father’s newspaper career. As a young man, Al reportedly studied at the Art Institute of Chicago.20 He began sketching baseball subjects during his minor-league years. When he arrived in New York, a cartoon of his tacked to the Giants’ clubhouse wall perked the interest of a New York American baseball writer, quite possibly Runyon. The American offered him a weekly gig at the onset of the 1913 season.21

These cartoons chronicled the Giants’ baseball life: the minutiae of long road trips, the battle with the Phillies (and their uncouth fans) for the pennant, Moose McCormick’s flashy suits, and the warbling of the team’s singing quartette (Ferdie Schupp, Fletcher, Grover Hartley, and Eddie Brannick). Professional indignities came more easily than heroics: ejections, humbling strikeouts, and reprimands from managers. Demaree mostly drew players as muscular roughnecks, with few defining personal features. But on occasion he provided a careful penciled study of a notable figure, such as umpire Bill Brennan.22

The Giants took a third straight pennant, and faced the Athletics in the World Series. Philadelphia won two of the first three games. McGraw went with Demaree in Game Four. The team behind him was banged up, and this led to an unearned run in the second inning when center fielder Fred Snodgrass could not reach a shallow fly, then first baseman Fred Merkle fumbled a foul popup. But by the second time Demaree went through the order, the Athletics teed off on his offerings, and added three more runs in the fourth. McGraw pinch-hit for Demaree the next inning.23 Philadelphia won the game, 6-5, and sent New York to its third straight World Series defeat the next day.

Despite overtures from the Federal League, Demaree signed a three-year deal with New York before the 1914 season.24 He started the campaign strongly, shutting out Brooklyn in his first start and outdueling Boston’s Dick Rudolph in his second. Then he struggled with his control, lost 12 of his next 16 decisions, and was relegated to the bullpen for stretches. The Giants, after leading the pennant race for most of the summer, were overtaken by the charging Braves, and finished in a distant second place. Demaree finished his sophomore season with a 10-17 record and a 3.09 ERA. McGraw, eager to upgrade the Giants’ third-base play, sent Demaree, Bert Adams, and Milt Stock to the Phillies on January 4, 1915, for Hans Lobert.

The deal capped a busy offseason for new Phillies manager Pat Moran as he remade an underachieving team. Demaree again was a mid-rotation arm, backing up Pete Alexander and Erskine Mayer. Following Moran’s advice, Demaree gradually abandoned his overhand delivery in favor of a side-arm one, similar to Alexander’s, with a longer stride. “As a result,” a Philadelphia reporter noted, “he now has greater speed and a better break to his fast ball.” Yet, if the stands were full of white-shirted fans – especially during the second game of a summer doubleheader – he might return to a more overhanded delivery. “By carefully studying his own delivery and the home field, Demaree can pitch in such a manner that the batsman cannot see the ball until it is upon them, owing to the moving background in the bleachers.”25

The Phillies didn’t wilt in the 1915 race, and the bleachers regularly moved. Demaree stumbled to a 1-7 start. But from July onward, Moran started him six times in the second game of a home-field doubleheader, with Demaree winning five of these assignments. He finished the campaign with a 14-11 record and a 3.05 ERA. The Phillies clinched their first pennant, then succumbed to the Red Sox in a five-game World Series. The closest Demaree came to seeing action was warming up in the bullpen during the final game.26

In 1916 Demaree again rebounded from a slow start. Over the course of two weeks in mid-September, he captured five consecutive complete-game victories, including both games of a September 20 doubleheader against the visiting Pirates. But the Phillies fell 2 1/2 games short of Brooklyn. Demaree amassed a 19-14 record and a 2.62 ERA.

Increasingly, Demaree and Moran “didn’t harmonize.”27 The pitcher was also “sort of a firebrand” with the Players’ Fraternity, calling for meetings in early 1917 as the union inched toward a possible strike.28 The Phillies washed their hands of Demaree, sending him to the Cubs for Jimmy Lavender. The union soon received a hammering from Organized Baseball. Demaree retreated from his prominent role in labor relations.29

The Cubs were a middle-of-the-pack team in 1917. Demaree again didn’t hit his stride until the dog days of summer. By this point, the Giants were headed toward the pennant. Yet McGraw’s staff lacked right-handed depth. Moreover, Demaree had been a consistent thorn in McGraw’s side since leaving New York, winning 11 games versus his former teammates since 1914. On July 31 New York obtained Demaree for Pete Kilduff and a reported $5,000.30 Demaree went 4-5 down the stretch for the Giants. That October, for the third time in six years, he saw no World Series action as the White Sox dismissed the Giants in six games.

In 1918 the Cubs overtook the Giants in early June. A month later a key five-game series opened in Chicago. For the opener, on July 6, McGraw sent Demaree to the hill to oppose the Cubs’ ace Hippo Vaughn. The two twirled shutout ball until Vaughn sent home the winning run with a walk-off two-out single in the bottom of the 12th inning. “It was,” an onlooker gushed, “in some respects one of the most skillfully handled games in the history of Base Ball.”31 New York finished the war-shortened 1918 season 10½ games behind Chicago. Demaree finished the campaign with an 8-6 mark and a 2.47 ERA, then worked and pitched in a Jersey City shipyard.

The Giants released Demaree that December and, after he pitched his services in the league meetings a few months later, his old skipper George Stallings signed him to a Boston Braves contract.32 Demaree finished the 1919 season with a 6-6 record for the seventh-place Braves. In February 1920 Stallings sold him to Seattle of the Pacific Coast League.

Demaree spent two seasons with the Rainiers, winning 16 games each year. But by late 1921 he was clashing with skipper Duke Kenworthy, and was ambitious to move into a managerial role of his own. Seattle sold him to the Western League’s Denver Bears. Demaree pitched for Denver at the onset of the 1922 season, then left the team, claiming a sore arm.33 He reappeared in July to take over the managerial reins for the PCL’s Portland Beavers.

A month later, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis placed Demaree on baseball’s ineligible list. Between Denver and Portland, Landis determined, Demaree had stopped off in Chicago and, in an effort to test his arm, pitched in semipro games with players already on the ineligible list.34 Demaree was reinstated a year later, and finished his pitching career with the American Association’s Columbus Senators at the tail end of the 1923 season, and in limited action in 1924.

Along Demaree’s stops, he found consistent work cartooning with local papers including the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Chicago Tribune, and Seattle Times. Beginning in 1922, his cartoons became a semi-regular feature in The Sporting News. Sometimes Demaree recycled previous themes in this work – such as a pitcher, trying to catch sleep the night before starting, being kept awake by boisterous teammates. Sometimes he played with contemporary storylines – like bored reporters trying to stroke Ban Johnson’s hostility toward Judge Landis. Sometimes, too, he used racist imagery common to the era, with African Americans drawn in crude stereotypes.35

Along Demaree’s stops, he found consistent work cartooning with local papers including the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Chicago Tribune, and Seattle Times. Beginning in 1922, his cartoons became a semi-regular feature in The Sporting News. Sometimes Demaree recycled previous themes in this work – such as a pitcher, trying to catch sleep the night before starting, being kept awake by boisterous teammates. Sometimes he played with contemporary storylines – like bored reporters trying to stroke Ban Johnson’s hostility toward Judge Landis. Sometimes, too, he used racist imagery common to the era, with African Americans drawn in crude stereotypes.35

This cartooning was mostly comedic in both caricature and action. By the mid-1920s Demaree was also producing sports columns for syndication. These were informative in nature: an illustration sketched faithfully from personal observation, accompanied by several paragraphs of text. Baseball topics included Ty Cobb’s batting grip, Charlie Root’s pickoff move, which quarters of the strike zone Babe Ruth’s home runs came from, Hack Wilson’s sliding catches in the outfield, and Howard Ehmke’s crossfire pitching motion.36 For younger ballplayers, Demaree covered general topics such as a catcher’s signs, how to tag out a baserunner caught in a rundown, or the wisdom of young pitchers not throwing too many curves.37 For a self-addressed, stamped envelope, he would mail a reader an illustrated leaflet on pitching, batting, or base-running.

As the Great Depression deepened, Demaree scrambled to adapt. By the 1930s, for his Sporting News efforts, he utilized a format similar to that of wildly popular Ripley’s Believe or Not. In 1934 and 1935, respectively, he illustrated baseball card sets for Chicago’s Dietz Gum Company and Schutter-Johnson Candy Company. In 1936 Demaree began drawing the Rube Appleberry daily comic strip, although this soon proved a funny-page dud.

By this time, his syndicated work had also dried up. After mid-1938 so did his bylined TSN contributions. His marriage to Alpha ended in divorce sometime during the decade; the couple had no children. On January 20, 1939, he was arrested for running out on a $47.20 hotel bill. “Demaree said,” it was reported, “he had been on a drinking spree and that $50,000 saved during his baseball career is now all spent.” The courts gave him several weeks to raise the money to pay the bill. But Demaree was unable to do so. Consequently, he was sentenced to serve 15 days in the county jail.38

Demaree’s work was considerably more limited afterward. He was briefly employed by the Peoria Star. In 1947 he moved to California. That year he contributed another card set, this time of PCL players for Signal Gasoline. Then, it seems, he drifted into retirement, eventually calling a Los Angeles hotel home. Interviewed in 1961, “Steamer Al” pronounced his life’s ambitions met: “I always wanted to be a major league baseball player, then a cartoonist and then just sit a hotel lobby with a big rich Havana in my mouth.”39 On April 30, 1962, Demaree died from cerebral arteriosclerosis. He was buried in Harbor Lawn Mount Olive Cemetery in Costa Mesa, California.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Demaree’s file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the following sites:

chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/newspapers/.

Illustration credit

The August 22, 1930, Altoona Tribune image appears courtesy of Newspapers.com and the Altoona Mirror.

Notes

1 “Slow Ball Pitchers Gone,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 23, 1917.

2 “Big Leaguers Are Drawing Cards on Semi-Pro Grounds,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 12, 1907.

3 “Demaree a Budding Star,” New York Sun, August 18, 1912; “Toft Pleasing Columbus Bugs,” Vicksburg Evening Post, April 15, 1908.

4 On Eaton joining Columbus, see “Broke Even,” Columbus Weekly Dispatch, May 21, 1908.

5 “Eastern League Events,” Sporting Life, August 29, 1908: 13.

6 Wm. F. H. Koelsch, “New York News,” Sporting Life, February 13, 1909, 5.

7 On Sally League shenanigans, see “Sally Season Over – At Last!” (Columbia, South Carolina) State, September 20, 1909; “Augusta Fans Hard Losers,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 20, 1909.

8 Eaton, not Al, twirled for Hopkinsville in the Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee in 1910. See “Eaton Demaree Sold to the Meridian Team,” Atlanta Constitution, April 3, 1911. Eaton soon fell out of baseball, and died in 1914.

9 John B. Foster, ed., Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide 1913 (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1913), 181.

10 “Giants Get Demaree,” Montgomery Advertiser, July 24, 1912; “Pittsburgh Pencillings,” Sporting Life, October 12, 1912: 4.

11 “Timely Bits of Sport,” New York Tribune, September 6, 1912.

12 “National League News in Short Metre,” Sporting Life, October 5, 1912: 10.

13 “Chance and McGraw Will Bid for Popular Favor in New York as Managers of Rival League Teams,” Montgomery Advertiser, December 15, 1912.

14 “Speculators Expect Choice Seats To-day,” New York Sun, October 6, 1913.

15 Damon Runyon, “Macks Knock Demaree Off Slab; Schang Batting Hero,” Chicago Examiner, October 11, 1913.

16 Sid Mercer, “Down Mobile,” April 4, 1937, newspaper article in Demaree’s Hall of Fame file.

17 Hans Wagner, “Hans Wagner’s Story,” Washington Evening Star, January 3, 1924.

18 Charles J. Doyle, “Champs Solve Adams; Score Three in First,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 21, 1916; “Giants Take Awful Beating to Aid 69th,” New York Sun, August 20, 1917.

19 “Down Mobile.”

20 “Al Demaree, League’s Best Hurler, Has Twirled Nine, Shut-Out Games; His Other Records Are Remarkable,” Atlanta Constitution, July 29, 1912.

21 “Baseball Notes,” Pittsburgh Press, April 8, 1913; “Al Demaree to Join Times Staff, Will Sketch for Seattle Fans,” Seattle Daily Times, February 22, 1920.

22 Many of the New York American cartoons were also featured in the Chicago Examiner, a sister Hearst paper, which is available online. See, for example: Al Demaree, “Let’s Be Joyful While We’re Happy,” Chicago Examiner, July 20, 1913; Al Demaree, “A Quiet Afternoon in Philadelphia,” Chicago Examiner, September 3, 1913; Al Demaree, “We Will Be Back With the Flag, Father,” Chicago Examiner, September 13, 1913.

23 For accounts of the game, see Bozeman Bulger, “Athletics Win Fourth, Hitting Demaree and Marquard With Ease,” New York Evening World, October 10, 1913; The Sporting News, October 16, 1913, 3.

24 “Federals Sign Up Pitchers Camnitz and Russell Ford,” New York Evening World, January 20, 1914; “Demaree Signs Contract,” Chicago Inter Ocean, January 21, 1914.

25 “Al Demaree a Different Pitcher Since He Has Adopted Side-Arm Delivery,” Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, August 3, 1916.

26 Damon Runyon, “Golden West Figured in Victory,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 14, 1915.

27 Harry Dix Cole, “McGraw the Peace Maker,” Sporting Life, February 24, 1917: 4.

28 William G. Weart, “Quaker Magnates in Striking Mood,” The Sporting News, January 25, 1917: 1.

29 Irving Vaughn, “Demaree to Desert the Frat,” Chicago Examiner, January 23, 1917; Robert F. Burk, Never Just a Game: Players, Owners, and American Baseball to 1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 210-216.

30 “Kilduff Traded for Steamer Al Demaree, of Cubs,” New York Tribune, August 1, 1917; Daniel [Dan Daniel], “High Lights and Shadows in All Spheres of Sport,” New York Sun, January 3, 1918.

31 John B. Foster, ed., Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide 1919 (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1913), 91.

32 Edward F. Balinger, “Moist Slant Gets Year of Grace but Others Are Banned,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, February 10, 1920.

33 “Al Demaree Shipped to a Bush League,” Oakland Tribune, March 21, 1922; “Dunn Changes Batting Order and Grizzlies Beat Witches in 11th,” Denver Post, April 30, 1922; Larry Dailey, “St. Joe Saints Open 3-Game Series Friday,” Denver Post, May 5, 1922.

34 “Al Demaree Deposed by Ball Powers,” Oregon Daily Journal, August 16, 1922; “Moser Will Ask Justice for Demaree,” Oregon Daily Journal, August 17, 1922; “Landis Backs Board,” New York Times, December 12, 1922.

35 Al Demaree, “That Night League Stuff,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1923: 3; Al Demaree, “Feeding the Stove League,” The Sporting News, November 29, 1923: 3; Al Demaree, “ ‘Intensive’ Training Stuff,” The Sporting News, February 22, 1923: 3.

36 Al Demaree, “Ty’s Hands-Apart Grip Gives Him Perfect Control,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 9, 1925; Al Demaree, “Big League Baseball: Holding Runner on First,” WashingtonEvening Star, April 29, 1930; Al Demaree, “Low and Outside Pitches Are Babe’s Only Weakness,” Indianapolis News, May 21, 1930; Al Demaree, “Need Lots Nerve and Skill to Put on Sliding Catch,” Dallas Morning News, July 23, 1930; Al Demaree, “Big League Baseball: ‘Cross Fire’ Ball,” Altoona Tribune, August 22, 1930

37 Al Demaree, “Big League Baseball,” Billings Gazette, April 14, 1925; Al Demaree, “Big League Baseball,” Winnipeg Tribune, August 19, 1930; Al Demaree, “Care of Arm,” Hamilton(Ohio) Journal News, June 28, 1932.

38 “Police Seek Demaree on Hotel Bill Charge,” Wilmington (Delaware) News Journal, March 7, 1939; “Al Demaree Is Sent to Jail for Two Weeks,” Chicago Tribune, March 17, 1939.

39 Bob Hunter, “Al Demaree Puffs Cigars, Recalls Old Days on Hill,” The Sporting News, November 29, 1961: 43; “Obituary,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1962: 43.

Full Name

Albert Wentworth Demaree

Born

September 8, 1884 at Quincy, IL (USA)

Died

April 30, 1962 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.